Abstract

The DataScapes Project is an exploration of how Augmented Reality objects

can be used as constituents for Landscape Architecture. Using Stephen Ramsay’s

Screwmeneutics and Harold Innis' Oral Tradition as our theoretical points of departure,

the project integrated the products of Data Art – the visualisation and sonification of

data – as the constituents for our two works: The Five Senses and Emergence.

The Five Senses was the product of protein data, while

Emergence was generated using text from the King James version of the Holy

Bible. In this exploratory treatment, we present the methods used to generate and display

our two pieces. We further present anecdotal, qualitative evidence of viewer feedback, and

use that as a basis to consider the ethics, challenges and opportunities that a future AR

Landscape Architecture will present for scholars in the Digital Humanities.

Our Aim: A new form of landscape architecture

There is a singular privilege that accompanies living in this first century of digital

computation: the opportunity to discern what it means. The task is nowhere near complete.

We know, or think we know, that computation is having a bearing on our capacities to

locate pattern, create and replicate pattern, and disseminate pattern. There are even some

who believe its advent will ultimately impinge on the trajectories of natural and human

history. Welcome to the Noosphere [

Teilhard de Chardin 1959]

[1]. The ambition of this exercise

in meaning-making is relatively more modest. We seek to explore how computation can be

used to support the human penchant to adorn one's surrounds. More specifically, our

purpose here is to explore how Augmented Reality (AR) Objects can be used as constituents

for Landscape Architecture. In the aftermath of Ivan Sutherland's foundational work in the

late 1960s establishing the field of computer graphics, the prospect that users might seek

to integrate computer-generated form with their surrounds became a plausible one, one

realized in the decades since via the medium of Augmented, and now Mixed, Reality [

ACM 1988]. In the ensuing decades, AR has emerged as an actual or potential

support for multiple fields, including education, construction, engineering, computer

gaming and firefighting. In this contribution, we present the efforts of

The

DataScapes Project to explore how AR's capacity to situate and register digital

content might be leveraged for artistic purposes: Augmented Reality content, combined with

constituents from Data Art, can be leveraged as raw materials for Landscape

Architecture.

Previous Work

The first challenge faced by members of the project was the fundamental one of

determining how to proceed. We were presented with a blank canvass and had to select the

location and method that, so to speak, would constitute our "paint." Choosing a location

proved to be the more straightforward of the two decisions. We were looking for a readily

accessible space at one of our two universities, a locale that at once presented a sense

of grand scale and a sense of enclosure. We were looking for a tract of land that would

serve as a frame and a complement for our AR artwork. Based on that criteria, we selected

the traffic circle at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario Canada. The circle is

140 metres in diameter, is centrally located on campus, and until recently was bounded by

willow trees.

Selecting the method and content that would constitute the matter of our creation, by

contrast, proved more difficult. To be sure, there were multiple domains of art that

anticipated – in part – what we were seeking to do. The fields of Landscape Art,

Earthworks, and Digital Art, through their creation of anamorph and

trompe

l'oeil artworks, for example, were suggestive of what an AR-based Landscape

Architecture might accomplish. But the three fields also differed significantly in their

practice from what we were aiming to accomplish. To start, while Landscape Art and

Earthworks both make location a central constituent of artistic production, artists in

both fields sculpt material objects – constituents from a local landscape – to generate

artistic form, not digital content [

Thompson 2014]

[

Herrington 2017]. In the domain of Digital Art, artists such as Joe

Crossley have sought to conflate the digital with the material by transforming static

empty spaces – generally building surfaces – into multi-media surfaces using projection

mapping. The content that is disseminated, however, is 2D, not 3D [

Crossley 2017].

Landscape Architecture, the primary field to which we sought to contribute, also did not

present an obvious theoretical frame of reference, method or aesthetic to assist our

efforts. One dimension of the problem here is that practitioners still tend to view

digital tools and content as instruments to support the design of physical landscapes. A

second problem is that the field's ontology of place is not sufficiently broad to

encompass the fusion of digital and physical that we sought to construct. Since the

Renaissance, landscape designers and gardeners, historian John Dixon Hunt argues, have

typically divided space into three constructs or "natures," with first nature referring to

wilderness, second nature to cultivated land, and third nature to landscapes shaped with

aesthetic intent [

Thompson 2014, 38]. Some designers suggest that

Landscape Architects should consider adding a fourth nature to the list, one encompassing

reclaimed landscapes and restored habitats, while we in turn wondered if we had stumbled

on a fifth: landscapes containing digital annotations, objects or complements.

A third issue centered on the field's self-definition. While Landscape Architecture

traces its origins to Landscape Gardening, the profession has maintained a complicated

relationship with the arts over the course of the 20th century. Then, many designers,

particularly in the wake of the profession's

1966 Declaration of Concern

[2],

suggested the focus of landscape architects should be on environmental conservation, not

the translation of artistic or philosophical trends, be it transcendentalism or

post-modernism, into landscape form. Other practitioners have taken the stance that the

primary focus of the field should be on design, here understood as landscape construction

that is optimized for the needs of a site's visitors and users. The artistic ambitions of

the architect are deemed to be a secondary concern, if they are considered at all. On the

50th anniversary of the 1966 statement, however, the Landscape Architecture Foundation

published a

New Landscape Declaration, one in which architects called for a

renewed emphasis on aesthetics [

Landscape Architecture Foundation 2017]. One reason for the call was

the realization that aesthetic concerns are not a luxury: poor design of buildings and

cityscapes – here understood as the mindless prioritization of utility over beauty or

meaning – has had a deleterious social impact. Landscape architects have also stressed

artistic concerns because of a widespread sense that the field has never been a site of

aesthetic innovation, and that it has missed important opportunities, such as the

emergence of avant-garde art in the early 20th century [

Corner 2017]

[

Fajardo 2017]

[

Jellicoe 1995]

[

Thompson 2014]. While the field has not been oblivious to important trends

such as Modernism and Post-Modernism, "there is surprisingly little discussion," Richard

Weller writes, "of what contemporary landscape aesthetics are and what they might yet

become" [

Weller 2017, 10].

Given this lack of definition, our team opted for an exploratory approach to inform the

design of our project, one akin in the Digital Humanities to Stephen Ramsay's

Screwmeneutics and Kevin Ferguson's Digital Surrealism. In his seminal essay, Ramsay

proposes a method of scholarly activity that eschews the conduct of what he refers to as

the "search." The "search" in this context is the practice of identifying a canon – the

state-of-the field for a given domain of research – and then identifying a gap in that

same canon. As scholars, we contribute to our respective fields by conducting research to

fill that gap. But there are times, Ramsay writes, when this formulaic approach does not

work, particularly when the researcher is attempting something new. How can the "search"

"help me find what I'm looking for," he writes, "when (a) I don't know what's here and (b)

I don't know what I'm looking for?" [

Ramsay 2014, 115]. For Ramsay, the

answer to this dilemma is to engage in what he refers to as "browsing." Drawing on the

ideas of Roland Barthes, Ramsay proposes that we engage in the construction of the

writerly text. In contrast to the

readerly text, which

involves a passive form of reading, engagement with a

writerly text

presupposes a process of composition, an immersion of the reader into the flux of

existence, and initiation of a process of discovery and systematization: the connection by

the reader of the content from the given text with a context, be it another item of

content, a person, or a compelling idea. The theory of the

writerly text,

Barthes writes, "is a practice (that of the writer), not a science, a method, a research

... this theory can produce only theoreticians or practitioners, not specialists (critics,

researchers, professors, students)" [

Ramsay 2014, 119].

Via this process, Ramsay argues, the humanist defines a path through culture, thereby

providing the Humanist – or, if you will, the Screwmeneuticist – with perspective, the

platform necessary to support discovery, desire and questioning. One useful first step in

defining such a pathway was undertaken by David Ferguson in his recent visual analysis of

Disney animations, where he brings his artistic artefact of interest – the film – into

relation with the concept of complex. Any artefact of interest, he suggests, can be

dissected and its components re-articulated into new combinations. However, while useful,

Ferguson's method for applying Screwmeneutics is not appropriate for our purposes for two

reasons. First, its aim is ultimately analytic, not generative. It seeks, like all

Structuralist methodologies, to locate the intrinsic properties – the hidden archetypal

structures – of a given art-form. Its purpose is not scenario exploration. It does not

seek to conduct an exercise exploring the potential ways an art-form

might

exist. It seeks instead to define the way a given form

already exists.

Second, and by extension, Ferguson's methodology, and structuralist methodologies in

general, are ones that collapse the dimension of time. They presuppose objects of analysis

that operate in a synchronic fashion [

Ferguson 2017]

[

Merrell 1975]. We, by contrast, were seeking to create Augmented Reality,

multi-media landscape complexes that could incorporate the dimension of time, and more

specifically would incorporate temporal art forms such as music. Our purpose, in the end,

was to generate an artwork that would serve, in Seymour Papert's words, as an

object-to-think-with, and in Barthes' words, as a

writerly text

[

Papert 1980]. Given that we were aiming to create something that was new,

we sought to construct an artefact that would provide definition, suggest potential, and

present questions and connections for future artists and humanists to explore.

Our Theory: The Oral Tradition of Harold Innis

For these reasons, we opted to employ a different Screwmeneutic method to conceive and

develop our landscape complex, namely Harold Innis' concept of the Oral Tradition. For

those unfamiliar with his work, Harold Innis was a media theorist and one of the founders

of the Toronto School of Communication. Between 1940 and 1952 he produced a set of works,

including

Empire and Communications and

The Bias of

Communication that were dedicated to exploring the physical, formal and cognitive

effects of communication media. A political economist by training, Innis turned to the

study of communications in 1940 because he perceived, not surprisingly, that the world was

falling apart. How was it possible, he asked in the final decade of his life, that the

world, after enduring the insanity and carnage of the First World War, should so readily

plunge itself into a Second? The answer, he believed, was to be found in the grand sweep

of global history. What factors, he wondered, enabled societies to thrive? And what, by

contrast, led to their dysfunction and eventual collapse? His lived experience, combined

with his studies of the past, convinced him that human collectives functioned much like

biological organisms. The vitality, adaptability, indeed the sanity, of institutions,

nations and empires were dependent on the environmental circumstances in which they found

themselves. Since the inputs and outputs of human-environmental interaction were largely

mediated by communication devices, Innis set high store on their importance in global

history. The political and cultural periodization of history, Innis believed, could be

correlated with the invention or adoption of new communication technologies. So could the

pathologies that afflicted cultures. There was a price to be paid for the unthinking use

of technology, and in his writings Innis pointed to two: cognitive rigidity and cognitive

flux [

Innis 1946]

[

Bonnett 2017]. Technology historically had produced pathological forms of

groupthink in which cultures either focused on the wrong thing (due to cognitive rigidity,

or bias), or no thing at all (due to cognitive flux). With its judgment impaired by one of

the two pathologies, a given culture would lose its ability to discern the opportunities

and threats latent in its environment, fail to innovate, fail to compete and as a result

fall prey to its competitors [

Bonnett 2013, 191–198].

It was a pessimistic construction of history, but it was not fatalist. While most regimes

inevitably went the way of Nineveh and Tyre

[3], Innis believed it was possible to construct a culture that retained its vitality

and resilience via an ethic he referred to as the Oral Tradition. The Oral Tradition, as

Innis conceived it, was not a call to forsake writing and adopt pre-literate Greek

communication practices that relied on memory and voice. Instead, like Barthes, Innis

called on his readers to adopt an

active stance toward knowledge, a

willingness to alter constructs and formalisms to meet the needs and experience of the

present. Such a stance, Innis argued, had enabled the Greeks to make their innovations in

theology, philosophy, science, politics and art. The Oral Tradition was also distinguished

by its reliance on linguistic and aesthetic formalisms that were characterized by internal

complexity and hierarchy. The power of such formalisms lay in their latent potential. They

contained multiple constituents that could be arranged and re-arranged at will, enabling

artists to explore new aesthetic constructs, and philosophers new intellectual

possibilities, through the separation, interpolation and translation of content. In its

essence, it was a serio-comic method, one that enabled Greece to shift its conception of

nature from one based on myth to one shaped by science [

Bonnett 2013, 209–217].

[4]A third feature of the Oral Tradition, one deriving from its commitment to active

manipulation of knowledge, was its use of multi-modal forms of expression. The reason

Innis named his communication ethic the Oral Tradition in the first place was due to the

influence of linguist Edward Sapir, who noted the "formal richness" of ancient

communication practices, practices that contained "a latent luxuriance of expression that

eclipses anything known to modern civilization" [

Innis 1950, 8–9]. Such

luxuriance of expression, and with it enhanced expressive potential, could be purchased in

the present by creating formalisms that combined written, vocal and visual forms of

representation. Such forms in principle presented possibilities for information

visualization – which would assist in the location of significant environmental patterns –

and information translation – which would enhance viewer understanding of the construct's

content [

Bonnett 2013, 166–181]

[

Innis 1946]. Referring to Italian artistic practice in the 15th and 16th

centuries, for example, Innis noted Andrea Alciati's invention of the emblem book, a

construct in which poetry, "one of the oldest arts, was combined with engraving, one of

the newest" [Innis 2015, 101] The rationale for so doing was provided by Francis Bacon,

who argued that emblems "reduce intellectual conceptions to sensible images and that which

is sensible strikes the memory and is more easily imprinted on it than that which is

intellectual'" [

Innis 2015, 101]

[

Bacon 1654].

The commitment to multi-modality in turn presented a fourth characteristic of the Oral

Tradition: a commitment to integrate both spatial and temporal forms of representation.

Because of its present and historic relationship with the art of poetry, Innis argued, the

Oral Tradition "implied a concern with time and religion. 'The artist represents

coexistence in space, the poet

succession in time' (Lessing at

the University of Berlin, 1810)" [

Innis 1951, 102]. In his own economic

work, Innis would apply this characteristic of the Oral Tradition by interpolating time

series of price data with maps to track the emergent patterns of North American economic

history, years before the practice become common via Geographic Information Systems [

Bonnett 2013]. The Oral Tradition was finally characterized by what in modern

parlance can be characterized as an open-source ethic, one in which content and form was

routinely lifted from one work and integrated into another. "The great epics," Innis

writes, "were probably developed out of lays constantly retold and amplified. Old ballads

were replaced by combinations of a number of episodes into a unity of action. The epic was

characterized by extreme complexity and unity" [

Innis 1950, 72].

Our Mode and Matter: Data Art, Protein and Text

In its essence then, the Innis' Oral Tradition is a method for intellectual inquiry and

aesthetic innovation that rests on a willingness to explore the possibility spaces

afforded by complex, spatio-temporal, multi-modal form, and to reconstitute that form

through the integration of content brought in from the outside. To assist our exploration

of the possibility space associated with digital Landscape Architecture, we opted to use

the methods and modes associated with Data Art. Also referred to as Information Art, Data

Art rests on the premise that the world is replete with forms that can be harvested for

artistic purposes. It chiefly emerged from scientific efforts to use sight and sound

analogues as a method to locate significant patterns and relationships in large data sets.

From that effort, multiple intriguing genres of art have emerged, particularly in the

field of music, such as DNA music [

Gena and Strom 1995], protein music [

Dunn and Clark 1999], microbial and meteorological music [

Larsen and Gilbert 2013],

and even a music of the spheres, music compositions derived from astronomical data [

Ballora and Smoot 2013]. With Data Art, we were presented in principle with a method

that would enable us to translate a given data set at once into visual and sonic form.

Once we had a mode for our AR landscape, the next, more difficult step was determining

its matter, the data that would provide the pattern, the source of serial distinctions for

our artworks. The team's decision-making here was determined by the following factors: our

decision to produce two works, contingent circumstance, and the intellectual interest of

project team members. The contingent circumstance centered on our need to locate

sonification software. While Bill Ralph, a mathematician, and Mark Anderson, a computer

scientist, respectively possessed the skills required to visualize our data, we had no one

with the requisite ability to translate raw data into musical form. After a fairly

protracted search (there is not a lot of proprietary or open-source software dedicated to

supporting the generation of Data Art) we were able to locate

MusicWonk, an

application developed by John Dunn, a pioneer in computer music and art since the

1970s

. While

MusicWonk is purportedly able to able to work

with any data set, the software specializes in supporting the creation of Genetic Music

from DNA and Protein Data. The application's website provides tutorials and links to

multiple libraries of genetic sequences, including the one we used: the U.S. National

Institutes of Health GenBank [

Algorithmic 2015]. Based on this

specialization, we opted to use protein data and to create an artwork called

The

Five Senses, a composition of five movements which would respectively be

constructed from protein data supporting Sight, Smell, Touch, Taste and Hearing in

humans.

Our data selection was also prompted by the team's interest in the construct of change

known as self-organization or emergent change, a ubiquitous phenomenon in the natural and

social sciences studied by the Science of Complexity [

Waldrop 1992]

[

Gell 1994]. It was also prompted by the observation of scholars such as

Werner Jaeger and Harold Innis that different domains of human activity – such as science,

philosophy and theology – often produce constructs of change that are very similar [

Innis 1950, 93]. It was finally prompted by the observation of John

Bonnett that a number of parallels could be found between the core concepts of emergent

change – such as positive feedback, the governance of formal cause, and the teleological

governance of system attractors – and the philosophy of history associated with the

Christian Bible. Economists, for example, often characterize positive feedback as the

Matthew Effect, given that the process of cumulative change it describes matches the

dynamic Jesus describes in the Parable of the Talents, where the rich became richer and

poor poorer [

Rigney 2010]. Given these parallels, we opted to create a

second work simply titled

Emergence based on source text from the Bible. Like

The Five Senses, we planned a composition featuring five movements, with

each piece named after a constituent concept of self-organization, respectively

"Emergence," "Differentiation," "Regulation," "Selection" and "Attractor." Each piece, in

turn, would rest on data taken from the King James version of the Bible, text that

provided narrative or mythic analogues to the concepts of positive feedback, formal cause,

and so on.

With the terms of composition settled, the team's next step was to identify the specific

data sets we wanted to use for each composition and then begin the process of

sonification. The proteins selected for

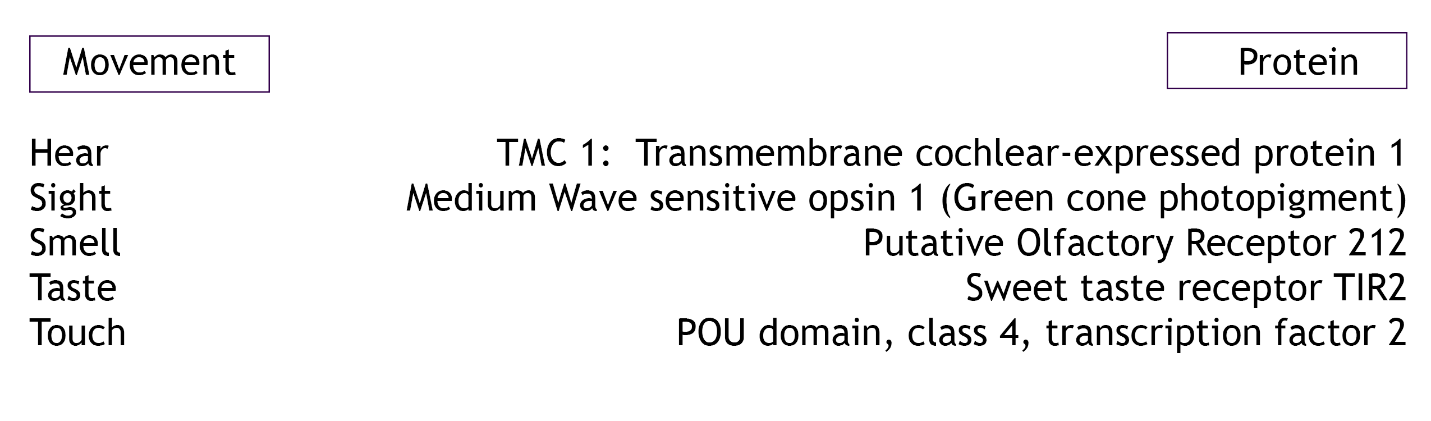

The Five Senses are shown in

Figure 1, while the biblical texts selected for

Emergence are shown in

Figure 2. The process

of sonification for

The Five Senses began by harvesting the letter data

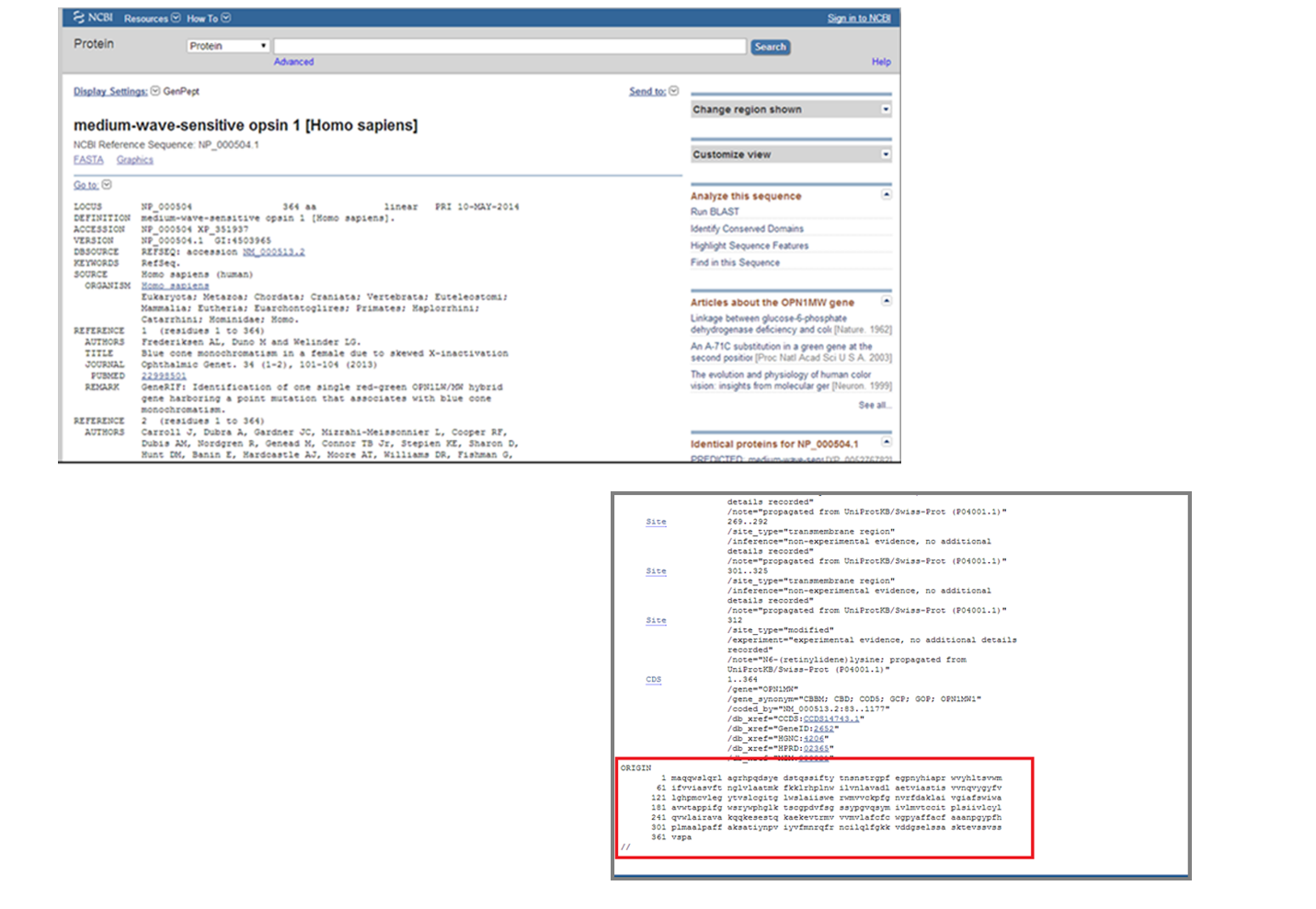

associated with each protein record, such as that shown in

Figure

3. In many ways, NIH protein records resemble what any researcher might find in a

library catalogue for a book listing, with metadata describing authors, key words,

versions and the like. However, NIH records also feature a sequence of letters where one

typically would find Library of Congress or equivalent subject headings describing a

book's contents. Those letters collectively constitute the protein described in the given

record. In

Figure 3, the highlighted letter sequence refers

to the amino acids making Medium Wave sensitive opsin 1 (Homo sapiens), a protein

contained in green cone photopigment that we used to generate the work

Sight.

These letter sequences provided the patterned sequences that would be translated into

notes for

Sight. Similar letter sequences generated the notation for the four

remaining movements of

The Five Senses, while the biblical passages provided

the initial basis for

Emergence.

Our Method of Sonification

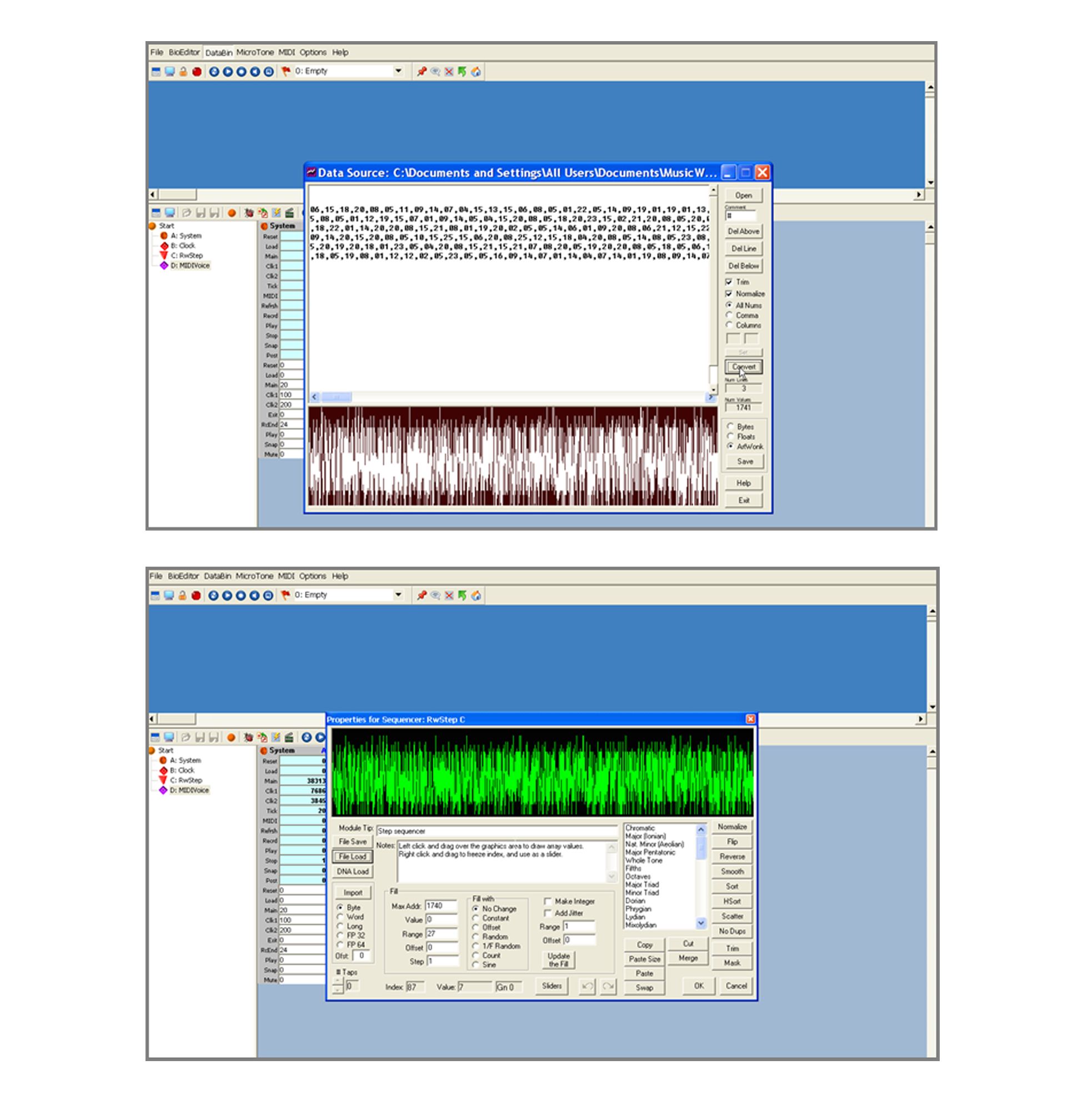

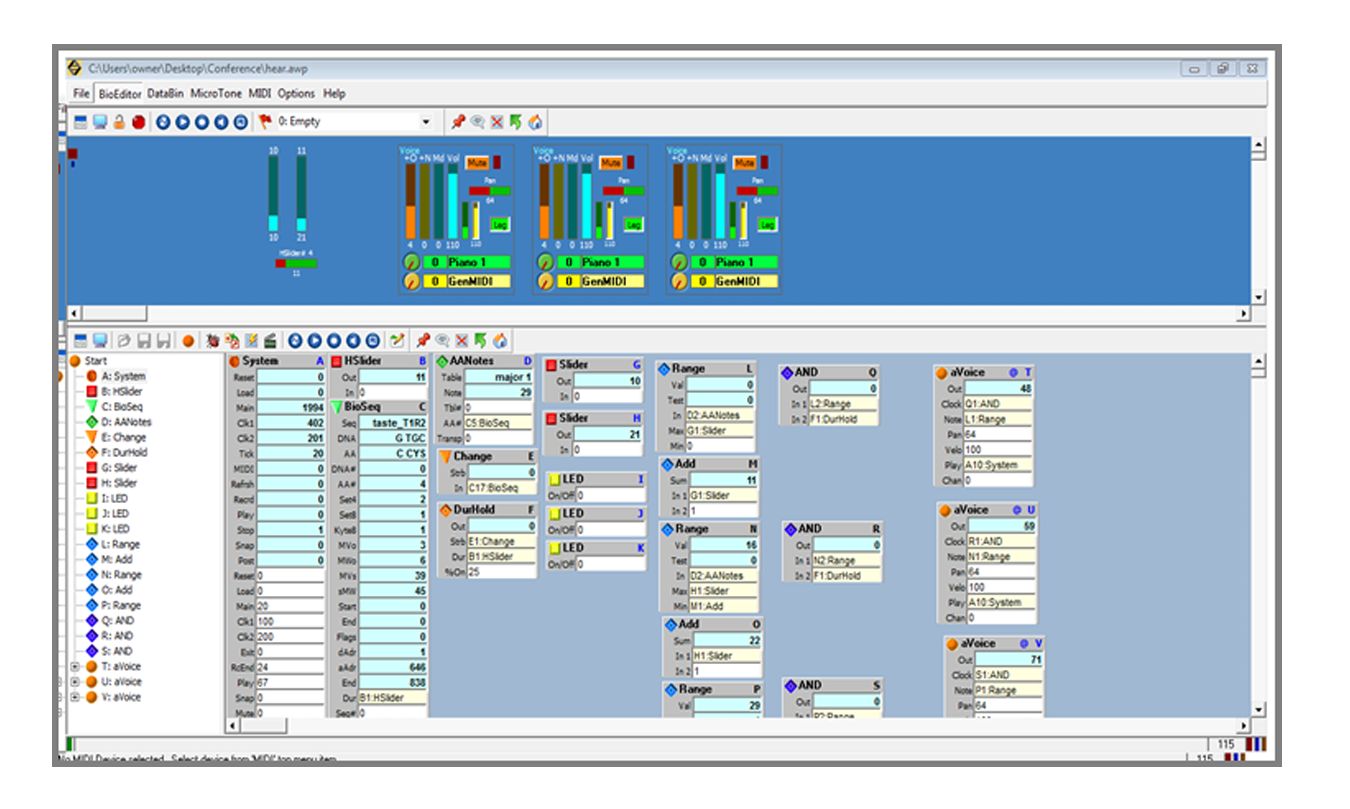

The process of sonification for both compositions was initiated in

MusicWonk

first by converting every letter from every dataset into a counterpart number, with A

equaling 1, B equaling 2, Z equaling 26, and so on. Once an entire letter set from a given

dataset had been translated, the software then aligned the numeric series with a specified

music scale, producing a raw music string, as shown in

Figure

4. From that point, the project's two music composers – Erin MacAfee and Amy

Legault – had two methods of composition and two modes of operating with their source data

open to them. The first method of composition – selected by neither – was to use the

algorithmic method of music composition supported by

MusicWonk. There, the

raw music string is transformed by feeding it through a set of components that control

features such as tempo, chords, instrumentation and the like. The process, shown in

Figure 5, is akin to creating an algorithm using a visual

programming language, or creating an electronic circuit.

The second method – selected by both – required the two to export the raw music string to

a *.midi file, and then open the exported file in Finale, a music composition

software package. The appeal of Finale for Legault and MacAfee is that it

presented methods for music notation that were familiar to them, most notably by featuring

an interface and tools that supported viewing and direct manipulation of music string

notation. With Finale, the two were able to alter note duration, inscribe

chords of their own devising, and repair aberrations in pitch.

Finale also enabled each composer to determine how she wanted to use the

musical sequences inherited from her source data. MacAfee's approach in The Five

Senses was minimalist. While she was willing to alter select attributes in her

file, such as rhythm, instrumentation and the duration of individual notes, she was not

inclined to alter the tonal sequence inherited from her datasets. Legault's approach, by

contrast, was more interventionist. Instead of viewing her inherited notation series as a

fixed object, she opted to view her raw music strings as libraries from which she could

splice identified musical components. The appropriated sections were – much like the lays

in Innis' Oral Tradition – placed in new sequences and were integrated into established

musical genres selected by Legault, such as the fugue.

Our Methods for Visualization

While Legault and MacAfee were generating their respective sonifications, team members

Bill Ralph, a mathematician, and Mark Anderson, a computer scientist, were working on

their visual correlates. Ralph is also an algorithmic artist, one who describes his work

as "an attempt to make a visual connection with the enormous complexity and unity that

lies within the rich mathematical objects that inspire my images" [

Ralph 2018]. He is particularly interested in mathematical objects that can generate chaotic,

dynamic systems, and has used them to generate dynamic and static works distinguished by

their complex topologies and colour. From the standpoint of this project, Ralph's approach

was ideal because it often relied on source data to drive the generation of a given work.

For

The Five Senses, he used proprietary algorithms driven by two inputs. The

first source of pattern was the set of distinctions obtained via a sequential progression

through the data. The second source was the set of relationships detected by the algorithm

between different, non-proximate strings contained in the data. Both were leveraged to

provide a visual focus to our landscape composition. For

Emergence, Mark

Anderson used a different approach. Instead of deriving his images from the data, he

selected Screen Vector Graphic images that related conceptually with concepts such as

Differentiation and

Attractor, and then used project data and

the application

NodeBox to animate each image and prompt transformations in

colour.

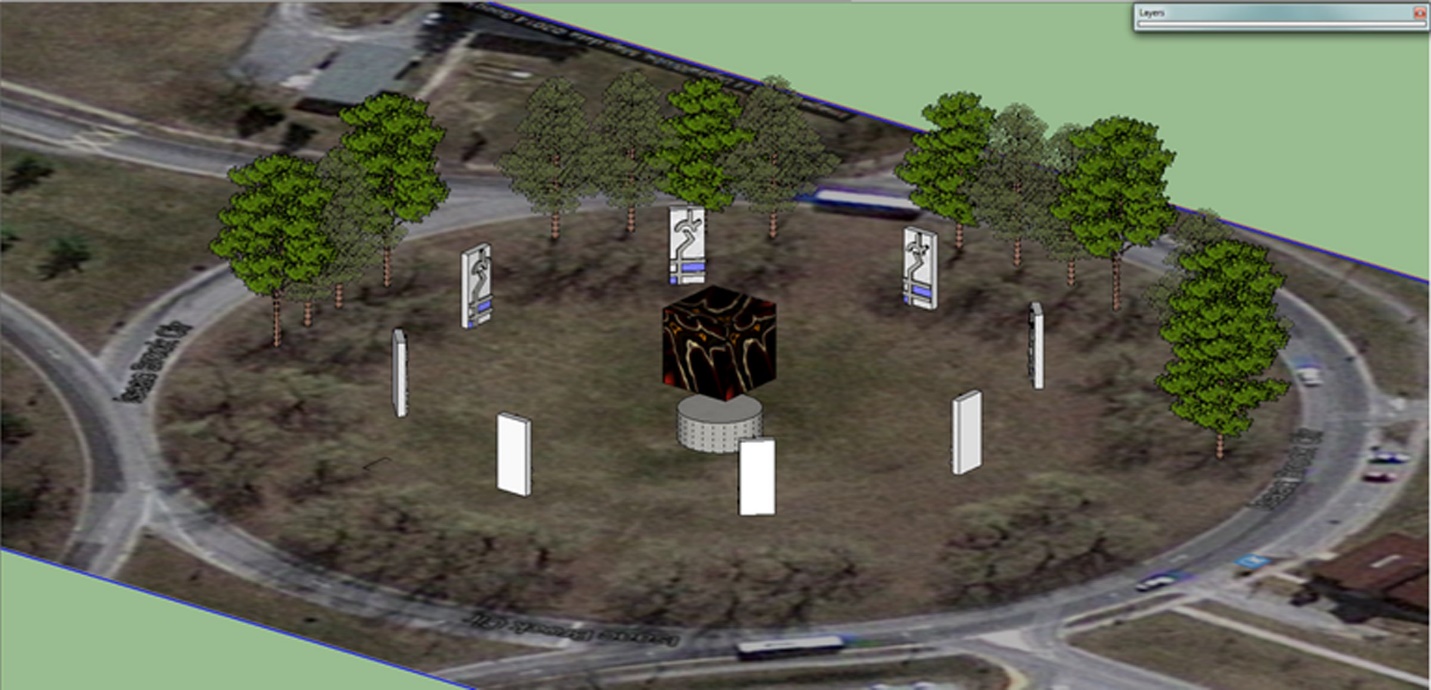

The DataScapes Project AR Set

With the sonification and visualization of our two works complete, two further tasks

remained, the first being the construction and overlay of a digital set to display

The Five Senses and

Emergence. Given that we conceived our two

works as Landscape Architecture, and that the Brock Traffic Circle – our selected first

venue – was 140 metres in diameter, the parameters of our project mandated that the

components of our digital set be relatively large in size for the visualizations to be

observable and for them in turn to serve as artistic complements to the surrounding

landscape. That need was further compounded by the presence of the physical statue, known

as She-Wolf, situated in the midst of the circle, and the scaffolding and the four 4.6

metre-high QR code signs we installed to activate and situate our digital works. All three

objects are shown in

Figure 6, and all three required

effacing by the digital set to prevent their disruption of the impact of our AR Landscape

works. Accordingly, the set shown in

Figure 7 was designed

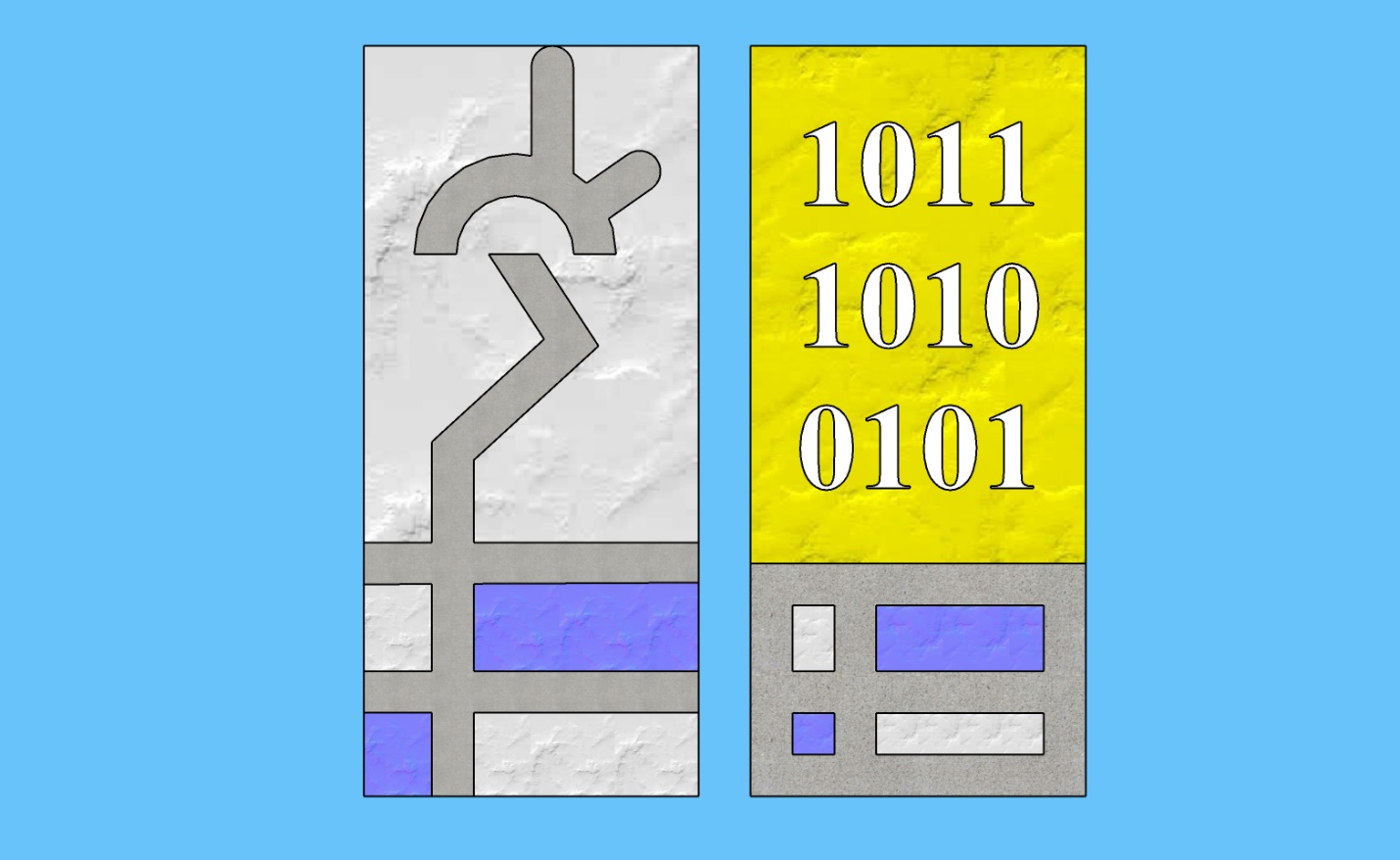

by John Bonnett using

SketchUp to display

The Five Senses and

Emergence. The set is bounded by eight 9-metre-high monoliths, with the

front of each monolith displaying a graphic representing the title of the movement

currently under display.

Figure 8, for example, shows the

graphics for the movement

Touch on the left and

Differentiation

on the right. The centre of the set is composed of two components. The cylinder at the

base is used to cover the statue, scaffold and QR code signs mentioned above. Floating

above it is a 9 metre object used to display the given movement's visualization. For

The Five Senses, a cube was used to display the artwork, while a sphere was

used for

Emergence.

The DataScapes Project Android App

Our final task was the creation of an Android app to support user viewing of the two

works via a tablet or phone. Our requirements for the DataScapes app were

straightforward. We wanted to simultaneously see and hear the respective visualizations

and sonifications associated with each movement. We further wanted multiple users to the

site to experience the performance in sync. If one viewer was viewing and hearing the

movement Taste, we wanted their counterparts to see and hear the same thing

at the same time. We also wanted user entry into the experience to be simple, involving

little more than user activation of the app, and direction of his

or her device camera at the QR signs situated in the middle of the traffic circle. The

app only worked at a distance of 6 metres or less from the QR code signs, to prevent

unsafe viewing of the exhibit by, for example, drivers circumnavigating the circle. The

DataScapes application was developed using Vuforia, an SDK

(Software Development Kit) designed to facilitate the development of AR applications on

mobile devices. Leveraging 3D objects, planar surfaces and patterns situated in the

environment, Vuforia is able to determine the user's position and camera

orientation relative to objects such as the project's QR Code signs, and in turn to

situate and register computer-generated 3D objects. These capabilities enabled team

programmers Joe Bolton and Mark Anderson to fulfill another requirement for the

DataScapes app: the capacity to move around and within the artwork.

Vuforia's capabilities, combined with GPS and gyroscopic data, enabled the

DataScapes app to track the movement of viewers, and in response to change

the orientation and rendering of displayed objects in real-time, to make our digital

objects seem as if they were integrated and locked into the natural landscape.

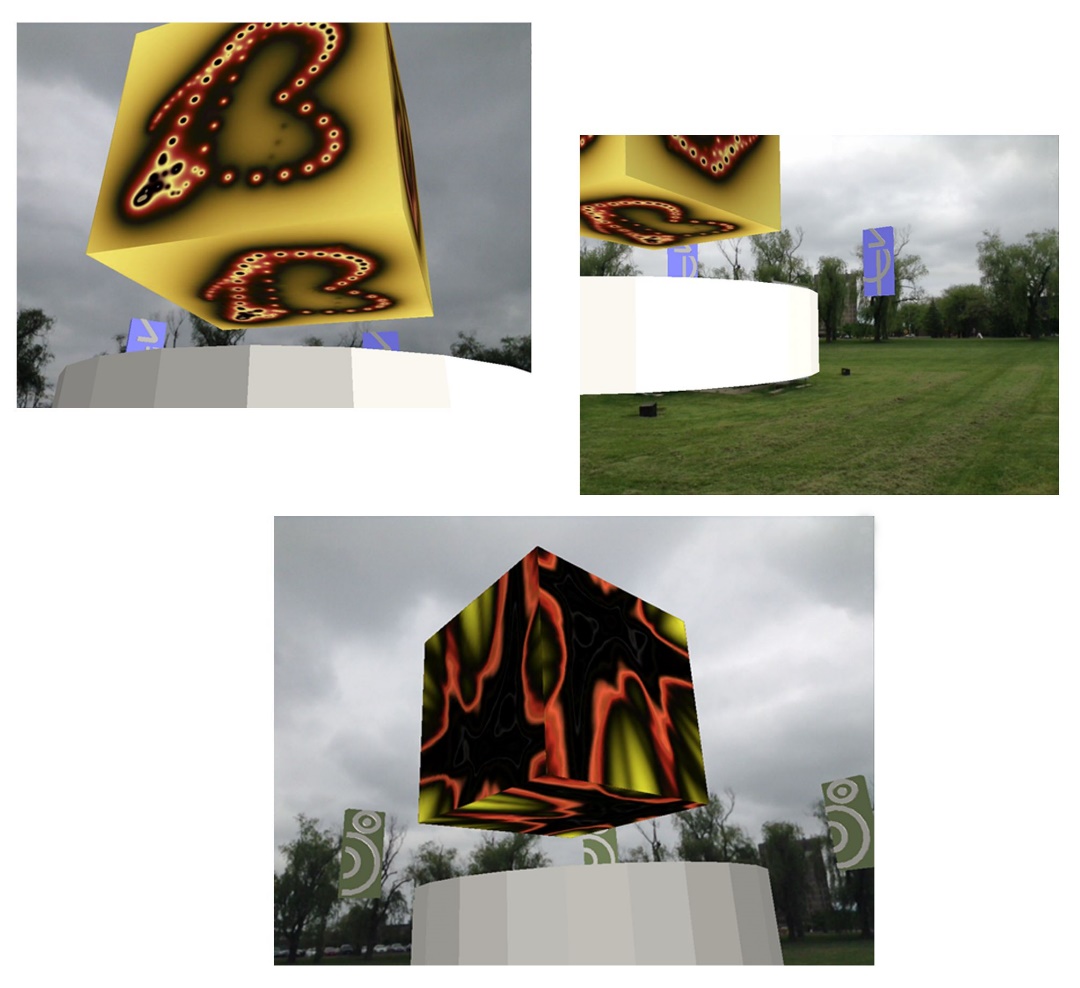

Results

The final results of our efforts are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, along with a video showing the operation of the

app in

Figure 11 (For an earlier treatment of

The

DataScapes Project, see Bonnett et al. 2018). The first version of the

DataScapes app in our estimation was a partial success, both technically,

and with respect to audience reception. With respect to the app's functionality, our

initial trials of the two works were hindered by two difficulties. The first and perhaps

most disappointing setback was the inadequate processing power of the two Asus 12" tablets

we had on hand for viewing the display. The tablets did not have the capacity to

simultaneously render and register our set while simultaneously displaying our data

visualizations in dynamic form. Despite our best efforts to find work-around solutions on

site, we had to settle for the necessary compromise of presenting Bill Ralph's and Mark

Anderson's respective visualizations in static form. A second difficulty centered on the

stability of the set. While the first version of the app adequately anchored our set to

the Brock traffic circle, several of its constituents, most notably its monoliths, tended

to vibrate or jitter in a way that was at once distracting and unpleasant. These

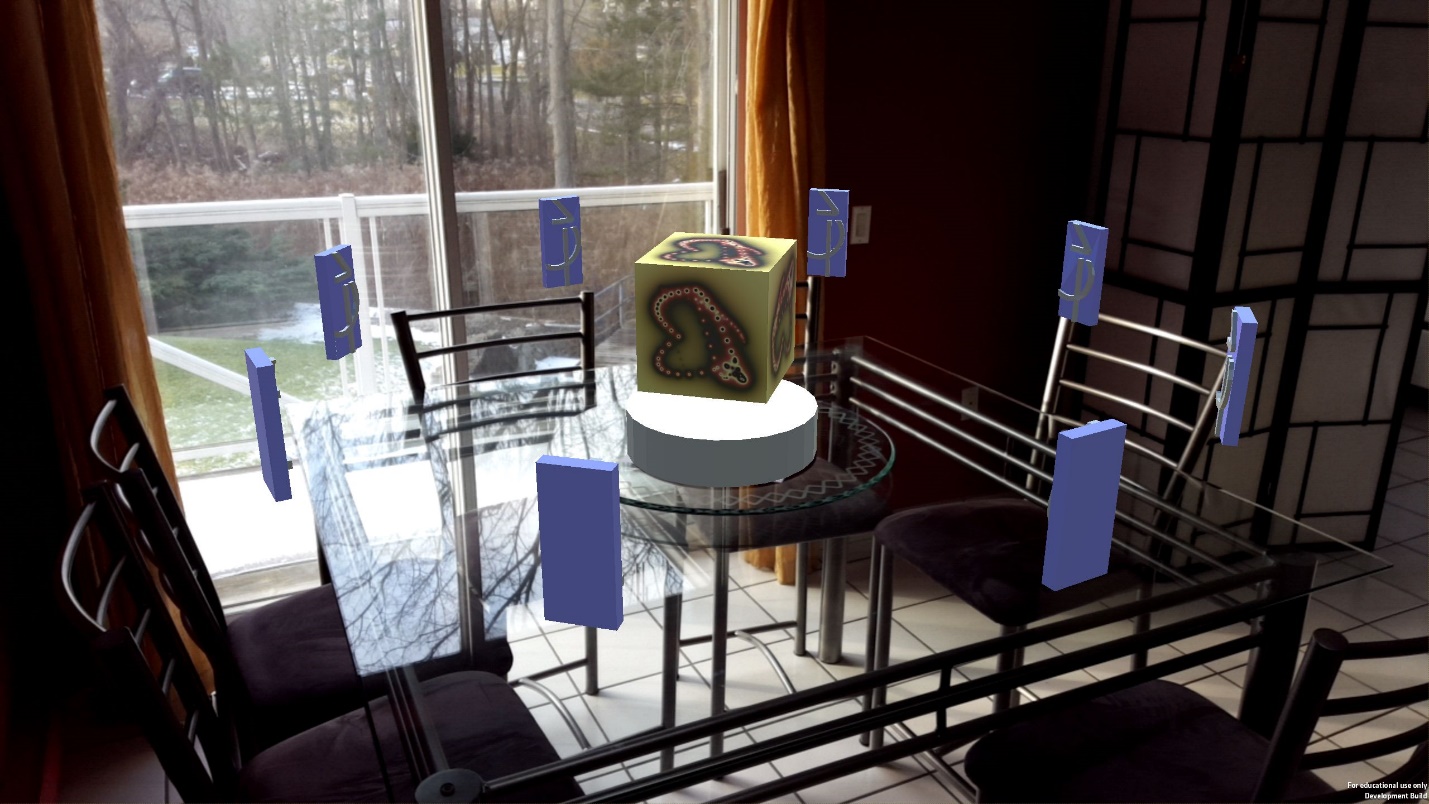

deficiencies have been partially remedied in the second and third versions of our app. Our

intention in these two iterations was to develop portable versions that would display

The Five Senses and

Emergence indoors, while remedying some of

the performance failures identified in the first. Version two, shown in the animation

featured in

Figure 12, was designed to support Mark Anderson

for an Edge Hill University lecture dedicated to the Art of Computing, and presents the

project as a wall display. Version three, shown in

Figure

13, transformed the orientation and scale of the project yet again, by adapting it

for display as a table-top installation. In both, we were able to better stabilize the

display of our set. And in both, we were able to add some dynamism to the display, albeit

by introducing movement into the set rather than our visualizations. Both iterations

required changes to the application, most notably by changing the way

Vuforia

searched for targets and changing the orientation of the 3D content it displayed in

relation to those targets. In addition, we also removed the initial application's use of

GPS tracking code, as that functionality was specifically designed to support the

geo-location of 3D content on the Brock traffic circle, and further designed to hinder the

display of content to users not on campus. Finally, we reduced the size of QR code

displays used with versions 2 and 3 of the

DataScapes app and designed each

version to generate displays proportional in size to the QR code target. Via this step,

the user can print a code on a piece of paper and generate a display proportional in size

to the underlying table.

As for audience assessment, we report here anecdotal evidence gathered during our first

trial. Our rationale for this approach as opposed to more extensive and expensive methods

used in Human Computer Interaction (HCI) and elsewhere is due, in part, to concerns

regarding the reliability of user assessment methods pioneered in cognitive psychology and

HCI. These methods have been drawn into question due to, on a general level, the

replicability crisis in the social sciences and, more specifically, widespread criticisms

of the two fields pointing to errors in statistical method, small sample sizes and large

confidence intervals [

Lundh 2019]

[

Greenberg and Thimbleby 1992]

[

Cairns 2007]

[

Gigerenzer 2004]

[

Cohen 1994]. Putting the matter simply, user assessment via this route

seemed to impose a good deal of effort for results that did not necessarily convince.

For the type of exploratory exercise that we were pursuing, it seemed more useful to take

a craft-based approach to user assessment. In fields such as web design, argues Gerd

Waloszek, a former interface designer with SAP, the metric for success for a given design

is not its authentication via an HCI analysis of design

consumers. The real

metric rests on whether other design

producers copy the design, making it a

convention [

Waloszek 2003]. In a different design context, Elizabeth

Eisenstein and Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt note a similar process in the history of the print

book. Through experimentation and appropriation of designs from competitors, printers such

as Peter Schoeffer collectively generated the conventions of the modern book, such as

tables of contents, title pages, running heads and footnotes [

Eisenstein 1979]

[

Lehmann 1950]. A craft-based approach, then, suggests that the "success" of

our effort will depend on whether other artists, landscape architects and digital

humanists choose to emulate our approach to landscape design, because they like it, and

because they believe it will induce a favorable reaction from their respective audiences.

The best we can do is report what we learned from our viewers and suggest the questions

and implications that stem from those observations. We will be "successful" if colleagues

choose to mimic those efforts and address the questions we have raised.

Based on that framework, we noted two classes of respondents – general viewers and

artists – and important questions that arose from each. General viewers for the most part

found our various pieces engaging, reporting an intrinsic fascination with the fact that

data, particularly protein data, could be translated into art forms, particularly music.

That feedback raised an important question for us, however. Is Data Art intrinsically

compelling on its own? Is it capable of generating an intellectual or affective response

from viewers without annotation, or must it be presented with an accompanying spoken or

written context to maintain viewer interest? This is, of course, not a new question in the

history of art and Landscape Architecture, where practitioners continue to argue whether

art should attempt to communicate a concept or message – such as the need for

environmental sustainability – or instead focus on generating an emotional response from

viewers [

Thompson 2014]. A related question is whether artists and Landscape

Architects can generate the sensory "languages," be it visual, sonic, olfactory or

something else, required to successfully communicate the artist's message to an audience

without textual assistance.

The response of artists was, perhaps not surprisingly, more searching and more critical.

While most viewers found the project's content and approach very interesting, some took

exception to our temporary appropriation of the Brock traffic circle (we used it for one

week), particularly since it already contained a physical statue that was surrounded by

the project's scaffolding and QR codes. One artist deemed the metal framing and the

statue's digital effacement problematic. Another deemed it a violation. This feedback

raised fascinating ethical and political questions for us. To be sure, the infrastructure

we constructed around the physical She-Wolf statute did hinder proper viewing

of the statue. Whether it constituted a violation depends on your point of view. Until

artists raised the issue with us, the construction of the scaffolding and QR codes

prompted no concern from project participants, nor did it for the university officials who

granted us permission to use the space. We meant no disrespect. It was not our intention

to make a comment on the statue, nor to damage it. But some artists did see our temporary

occupation of the space as an unacceptable abridgement on the statue's integrity and the

sculptor Ilan Averbuch's rights.

One response to these concerns would be to note that the scaffolding and QR codes will

not be a permanent component of AR Land Architecture, or more generally, AR-based artforms

in future. We used them because current technology requires their use to situate and

register content. In future, artists will be able to use RTK GPS (Real-time Kinematic

Geographic Positioning System) data to position content with centimetre and even

millimetre level accuracy. That expedient will resolve the issue of the art form's

physical intrusion into a given space, but not its digital annotation. Is it ethical for

one artist to use digital methods to efface, comment upon, add to, mock, or alter the

context of a physical artwork created by another, even if the digital annotation is not

visible to the naked eye? To that ethical question we can add a political one: who gets to

add that annotation? The complexity and sensitivity of this question was anticipated in

2017 in New York when the statue

Fearless Girl (sculpted by Kristen Visbal)

was placed in proximity to the statue

Charging Bull, a work situated on

Broadway and long associated with Wall Street and the city's financial district. To many,

Fearless Girl presented an important message of female empowerment.

Charging Bull's sculptor Arturo Di Modica, however, was outraged, arguing

that

Fearless Girl's proximity and positioning transformed the meaning of his

statue, from one symbolizing prosperity and strength, to that of villain [

Dobnik 2017]

[

Mettler 2017]. The controversy raised multiple questions, ones that we now

face with our project. When an artist makes an intrusion into a space, does that space

become sacrosanct? Artists have long made interventions into spaces that they deem to be

playful, even provocative. Are those intrusions to be exempted from three-dimensional

annotations that some will label as legitimate super-positions or rejoinders, others as

graffiti, and others as outrageous violations? Who gets to decide the issue? These issues

will become increasingly central as AR becomes a ubiquitous communication medium.

Discussion and Conclusion

In addition to the questions posed above, what other observations and questions might we

offer to conclude this exercise in Screwmeneutics via the Oral Tradition? In our view, the

best way to finish would be to explicitly address the questions that constitute the heart

of this issue of DHQ.

1. What are digital and computational approaches to sound, images and time-based

media?

For this project, the answer is simple: data translation. Data translation via

computation can be used to generate sound (via sonification), images (via

visualization), and time-based media (music via sonification). Further, this project is

significant in the context of the digital humanities because of its use of approaches

typically used for analysis to generate art. In the last 10 to 15 years, visualization

has become an integral component of text analysis, while tentative steps are also being

taken to leverage sonification [

Sinclair and Rockwell 2016]

[

Graham 2016]. The project also makes a contribution by leveraging text

data, typically the grist for DH analysis, as the raw material for art. It finally

contributes by using a non-traditional DH data source, protein, as a constituent for

art.

2. How do these methods and approaches produce new knowledge and shift scholarship

in a particular scholarly domain?

In the domain of Landscape Architecture, as indicated above, digital objects have

typically been seen as instruments for planning, the basis for the physical

transformation of a given landscape. This project suggests that Landscape Architecture –

and, by extension, the Digital Humanities – should integrate the digital with the

physical when producing new landscape designs, and in so doing should generate a new

domain of Landscape Architecture. The reason for so doing rests on a long-standing

ambition of the field: to use landscapes as a visual way to say something about the

nature of the cosmos in which we find ourselves. For example, pioneers such as Frederick

Law Olmsted, the designer of New York's Central Park, were Transcendentalists. They used

landscapes to express their sense that there was a latent reality underlying nature,

that it was suffused with the divine [

Thompson 2014].

Landscapes populated by latent, invisible without instrument, AR objects could be used

to extend a similar, but different, message. In this context, the construction

disseminated would not be

transcendence, but

ubiquitous

sentience. In the past 20 years, biologists have made numerous remarkable

discoveries that suggest many supposedly human distinctives are not unique to our

species at all. Trees, for example, form familial and friendship networks, and

communicate via something akin to a fungal Internet [

Wohlleben 2015].

Cetaceans have been shown to use artificial languages and form cultures while musical

biologists suggest birds compose music equal in complexity to symphonies [

Conway 2003]. Perhaps most surprisingly, recent work in molecular biology

suggest that cells use molecules in a fashion akin to words, that their communication is

possibly akin to language, with a semantics, syntax and pragmatics, that they

communicate in more than one "language," and that they vote (biologists refer to it as

quorum sensing) [

Ahmed 2008]

[

Bassler 2009]

[

Ben et al.2004]

[

Ji 1999]. Landscape Architects have long had a commitment to design that

reflects an ethic of ecological sustainability and highlighting plant life, stone and

other constituents of their local regions. To our knowledge, those same architects have

not produced designs that in humanist terminology reflect an

Animal Turn, a

commitment to highlighting the agency embedded in environments that individuals in

modern, European-derived cultures have traditionally ignored, largely because they – and

we – were ignorant of their existence. It would be a worthy challenge for Landscape

Architects to derive an AR-based visual language to focus viewer attention on our

neighbours. DNA, molecular and Protein Data – the "words" used by single cell organisms

to communicate – would be particularly worthy material upon which to build that

language.

For the Digital Humanities, our exercise in Screwmeneutics via the Oral Tradition

suggests that scholars have the potential to translate their traditional focus – text

data – into visual and sonic forms of art. They also can join their colleagues in the

arts and sciences in translating other forms of data for the same purpose. The exercise

also suggests that so long as the intrinsic structure of source data is retained, there

is no correct, preferred or consistent method for generating Data Art. The source data

can be divided into its components, and, again, provided the internal structures of

those components are retained, the appropriated sections can be placed in new sequences

and contexts. Further, the components of a given data source can be situated with

whatever form, medium or context that is consistent with the needs, aspirations and

capabilities of the artist. To be sure, most artists in domains such as Protein Music

and other forms of Data Music choose to retain the sequential structures of their source

data in their entirety. But the insights of the Oral Tradition and the inherent

structure of our protein and text source data suggest that this preference need not be

so, and our experience, combined with the past behavior of some Data Artists, suggests

that some will do so.

With respect to the nature of our data, Douglas Hofstadter notes that proteins like

music are composed of smaller components: "Music is not a mere linear sequence of notes.

Our minds perceive pieces of music on a level far higher than that. We chunk notes into

phrases, phrases into melodies, melodies into movements, and movements into full pieces.

Similarly, proteins only make sense when they act as chunked units" [

Hofstadter 1979, 525] Biologist Mary Anne Clark similarly notes that "I

was struck by the parallels between musical structure and the structure of proteins and

the genes that encode them. Proteins also seemed to be composed of phrases organized

into themes. For years I was haunted by the image, and tried occasionally to interest

musicians in making the transformation for me ..." [

Dunn and Clark 1999, 25].

Similar observations can and have been made about the complex nature of linguistic and

textual data, not the least, as we saw, by Harold Innis in his descriptions of the Oral

Tradition.

Our stance that some Data Artists, particularly digital humanist Data Artists, will opt

to leverage the "phrases" and "themes" of data for artistic purposes, and connect them

to the instrumentation, media or objects that suit their purpose, is indicated by the

choices made by the artists who collaborated on The Five Senses and

Emergence. In the first work, Erin MacAfee and Bill Ralph chose to work

within the sequential confines of the data presented to them. In the second, Amy Legault

and Mark Anderson did not, collectively producing a work that confined the Data Art to

the sonic level, based on selections of phrases detected by Legault in the source data,

and the selection by Anderson of non-data images derived from an on-line library. In

each case, the artists subjectively chose the extent to which they would subject

themselves to the structures contained in their data, and the objects, media and

instrumentation they conflated with their data. That is no different in principle from

what previous Data Musicians have done, where they have displayed a remarkable degree of

ingenuity and freedom in the artistic choices underlying their compositions. In our

work, we played with complexity, arranging and re-arranging units contained on a single

level of biological organization. In previous work, sonic composers have played with

hierarchy, subjectively conflating structure from different levels of biological

organization – such as DNA data, amino acid data, and protein folds – to produce a

composition. Our work has been an exercise in juxtaposing retrieved structure with

selected visualization. Previous work has juxtaposed identified structure with selected

instrumentation. The key point here is that strict adherence to a given method is not

necessary for Data Art to retain its integrity. So long as some trace of the data's

original structure is retained, one should expect artists, as they must, to exercise

their own judgment on what method or array of methods is legitimate to fulfill their

purpose.

3. What are the Challenges and Possible Futures for AV in DH?

Our combined use of Screwmeneutics, Harold Innis' Oral Tradition and Digital Art has

explored one potential way that AR-based objects can be leveraged as constituents for

Landscape Architecture. The Possibility Space for spatial AR art, however, is much

larger, and its exploration and realization would constitute a worthy possible future

for the Digital Humanities. One obvious way that space could be explored would be to

change the digital content that is used to populate selected landscapes. Data Art is and

will remain a central constituent of our future work. Indeed, we intend to further

refine our app so that future users can incorporate their own visual and sonic

constructs from data into it. But we also intend to incorporate other forms of art. We

find ourselves, for example, wondering what the surreal imagination of Salvador Dali

might have made of AR as a medium. The sky is a constant backdrop in his paintings, as

witnessed in masterworks such as Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee,

Christ of Saint John of the Cross, and Santiago el Grande.

One only has to survey a few of his works before the question arises if other spaces

might be filled by AR objects. We are used to thinking of Landscape Architectures.

Dali's work suggests AV digital humanists ought to expand their imagination to consider

what a Skyscape Architecture or Seascape Architecture might look like.

Two factors, one old, one new suggest why they might want to consider the development

of such architectures. To start, it is a commonplace to observe that architects and

interior designers, since ancient times, have sought to shape a visitor's experience of

interior space – a given room inside a building – by importing select features from

exterior space, ranging from the physical to the metaphysical. Whether by landscape or

trompe l'oeil paintings, alignment of windows, doors, and ceiling oculi

with the sun and moon, paintings with celestial motifs, or religious paintings such as

Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam, artists have sought to use exterior

space to create a sense of interior place. A second factor that should influence digital

humanists is the imminent availability of smart glasses, as well as intelligent glass

supported by smart film. Both present the possibility for immersive AR that outstrips

the constrained field-of-view presently afforded by tablets and head-mounted displays.

While smart glasses – which will be light, easy to wear, and feel like regular glasses –

suggest the possibility for user access to AR content anywhere at any time, intelligent

glass and smart film – sheets of glass and film that can alter glass opacity and display

information – suggest the possibility that digital humanists and interior designers will

be able to conceive and construct augmented seascapes and skyscapes.

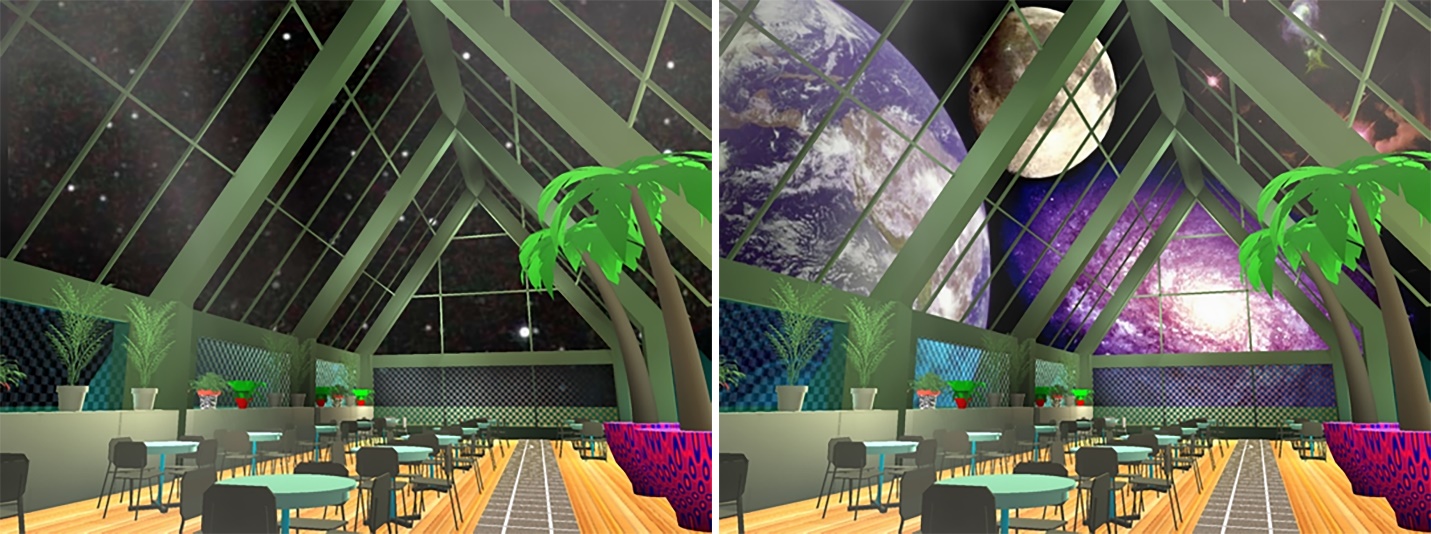

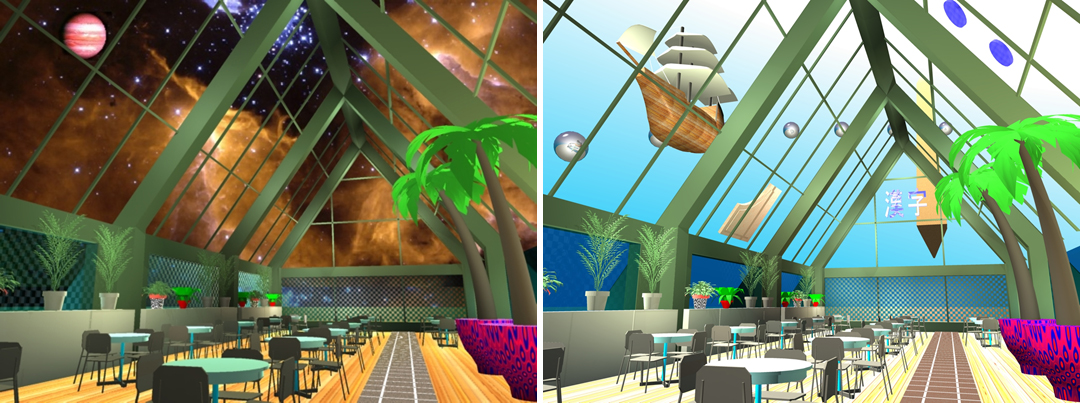

Consider the following storyboard as a possible example of what might result from an

architect's attempt to construct a Skyscape Architecture using intelligent glass.

Typically, the night-time sky in a city is a rather dull place. Light pollution effaces

many if not most of the stars that might be observed, plus the Milky Way. An architect,

say, of a restaurant might choose to exploit this gap by creating an A-Frame structure

topped by a roof made with glass and smart film. The architect or interior designer, in

turn, would then be free to fill the evening sky with whatever object, or array of

objects is wished. Drawing on ceiling celestial paintings as a source of inspiration,

our architect might opt to create a surreal display conflating the earth and moon with

the Andromeda Galaxy, as shown in

Figure 14. The

restauranteur taking possession of the locale, however, would not be constrained by the

initial skyscape provided by the architect, and could supplement it with other designs

displaying other astronomical objects and other styles. The next evening our

restauranteur might choose to populate the evening sky with an enlarged version of

Jupiter juxtaposed with part of the Rosette Nebula. The following day, patrons would be

treated to a surreal display of objects floating in the sky, as indicated in

Figure 15.

In such a scenario, building architecture would emerge as an interface to a new domain

of art. And in such a scenario, sea, land and sky would emerge as platforms for the very

sort of meaning-making that we have sought to promote in this study. Nothing is

inevitable, but we would be very surprised if artists and digital humanists do not avail

themselves of this opportunity to use digital form to enhance their surrounds. Such a

step would simply be a continuation of a long history in which humans have used built

form and modified topography for more than functional purposes. "From the most

immemorial Hindustan pagodas to the Cathedral of Cologne," Victor Hugo writes in

The Hunchback of Notre Dame, "architecture was the great script of the

human race." Landscapes and buildings have been used by humans to express their yearning

for beauty; their conception of history; their power over space; and their belief that

humans – in the end – live in a cosmos with intrinsic purposes that can be understood.

Now, that conversation, and that quest for meaning, can be continued in digital form, in

new locales. And now, that conversation – in visual, sonic and topographic form – can

express in a powerful way that the planet is replete with agency, creativity and

dignity. We have no idea what our peers and our successors will produce. But we expect

it will be replete with all the usual adjectives that we associate with great art:

compelling, interesting, at times infuriating, but never boring.

Works Cited

Algorithmic 2015 Algorithmic Arts , “Interactive Generative Creativity Software for Music, Visuals and

Wordplay”

Algorithmic Arts, (2015).

http://algoart.com [Accessed 27 May 2020].

Bacon 1654 Bacon, Francis, De

Dignatate et Augmentis Scientarium, Book 5, Chapter 5, Argentorati: Sumptbus,

Johan Joachimi Bockenhoferi (1654).

Ballora and Smoot 2013 Ballora, M. and Smoot, G.S.,

“Sound: The Music of the Universe”

The Huffington Post, February 23, (2013),

https://bit.ly/2Yx2MAF [Accessed 27 May

2020].

Bassler 2009 Bassler, Bonnie, “How

bacteria 'talk'”Ted Talks, (February 2009).

Available at: https://bit.ly/36C0IeR [Accessed 28 May 2020].

Ben et al.2004 Ben Jacob, Eshel, Becker, Israela, Shapira,

Yoash and Levine, Herbert, “Bacterial Linguistic Communication and

Social Intelligence”, Trends in Microbiology 12(8)

(2004): 366–372.

Bonnett 2013 Bonnett, John, Emergence and Empire: Innis, Complexity and the Trajectory of

History. Montreal, McGill-Queens University Press

(2013).

Bonnett 2017 Bonnett, John. “The Flux

of Communication: Innis, Wiener and the Perils of Positive Feedback”

Canadian Journal of Communication 42(3) (2017),

431–446.

Bonnett et al.2018 Bonnett, John, Ralph, William, Brulé,

Dempsey, Erin, Bolton, Joe, Anderson, Mark, Winter, Michael and Jaques, Chris, “The DataScapes Project: Using Letters, Proteins and Augmented Reality as

Constituents for Landscape Art”

Annual

Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 16: 160–165 (Summer

2018).

Cairns 2007 Cairns, Paul, “HCI. . .

Not as It Should Be: Inferential Statistics in HCI Research”

BCS-HCI '07: Proceedings of the 21st British HCI Group Annual

Conference on People and Computers. Eds. L.J. Ball, M.A. Sasse, C Sas , Swindon,

UK: BCIS Learning and Development, (2007)195–201.

Cohen 1994 Cohen, Jacob, “The World is

Round (p < .05)”

American Psychologist 49(12) (December 1994):

997–1003.

Conway 2003 Conway Morris, Simon, Life's Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely

Universe, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

(2003).

Corner 2017 Corner, James, “Landscape

City”, The New Landscape Declaration, ed. Gayle

Berens, Los Angeles, CA: Rare Bird Books. (2017), pp. 65–68.

Crossley 2017 Crossley, Joe, “How We

Can Hack the Surfaces around us with Projection Mapping”

TEDx Talks,

https://bit.ly/2Toc1lm [Accessed 27 May 2020].

Dobnik 2017 Dobnik, Verena, “Will New

York invite the 'Fearless Girl' statue to stay on Wall Street?”

USA Today, March 27 (2017). Available at:

https://bit.ly/3gtadBr [Accessed 27 May

2020].

Dunn and Clark 1999 Dunn, J. and Clark, M., “The Sonification of Proteins”

Leonardo 32 (1)(1999): 25–32.

Eisenstein 1979 Eisenstein, Elizabeth, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change:

Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early Modern

Europe, Volumes I and II. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press. (1979).

Fajardo 2017 Fajardo, Martha, “Manifesto About the Profession's Future”, The New

Landscape Declaration, Gayle Berens (eds), Los Angeles, CA:

Rare Bird Books (2017), pp. 119 -122.

Ferguson 2017 Ferguson, Kevin L., “Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios”

Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11(1) (2017). Available at:

http://www.digitalhumanities.org//dhq/vol/11/1/000276/000276.html [Accessed 27 May

2020].

Gell 1994 ]Gell-Mann, Murray, The Quark

and the Jaguar, New York: Henry Holt and Company. (1994).

Gena and Strom 1995 Gena, Peter and Strom, Charles, “Music Synthesis of DNA Sequences”

Sixth International Symposium on Electronic Art, Montreal

(1995): 83–85.

Gigerenzer 2004 Gigerenzer, Gerd, “Mindless Statistics”

The Journal of Socio-Economics 33(2006): 587–606.

Graham 2016 Graham, Shawn, “The Sound

of Data (a gentle introduction to sonification for historians)”The Programming Historian. Available at:

https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/sonification [Accessed 28 May 2020].

Greenberg and Thimbleby 1992 Greenberg, S. and

Thimbleby, H., “The Weak Science of Human-Computer Interaction”

CHI '92 Research Symposium on Human Computer

Interaction, Monterey, California, (May 1992). Available at:

https://bit.ly/2M6nfH3 [Accessed 27 May

2020].

Herrington 2017 Herrington, Susan, Landscape Theory in Design, London: Routledge. (2017).

Hofstadter 1979 Hofstadter, Douglas, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Hassocks, Sussex,

UK: Harvester Press. (1979).

Innis 1946 Innis, Harold, Political

Economy in the Modern State, Toronto: The Ryerson Press. (1946).

Innis 1950 Innis, Harold, Empire and

Communications, Oxford, UK:The Clarendon Press. (1950).

Innis 1951 Innis, Harold The Bias of

Communication, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (1951).

Innis 2015 Innis, Harold Harold

Innis's History of Communications, William J. Buxton, Michael B. Cheney, Paul

Heyer (eds), foreword by John Durham Peters, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

(2015).

Jellicoe 1995 Jellicoe, Geoffrey, The Landscape of Man: Shaping the Environment from

Prehistory to the Present Day , 3rd edition, Thames &

Hudson. (1995).

Ji 1999 Ji, Sungchul, “The Linguistics of

DNA: Words, Sentences, Grammar, Phonetics, and Semantics”

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 870 (May

18,1999): 411–417.

Landscape Architecture Foundation 2017 Landscape

Architecture Foundation, The New

Landscape Declaration, Gayle Berens (eds), Los Angeles, CA:

Rare Bird Books. (2017).

Larsen and Gilbert 2013 Larsen, P and Gilbert, J., “Microbial Bebop: Creating Music from Complex Dynamics in Microbial

Ecology”

PLoS ONE 8: e58119 (2013).

Lehmann 1950 Lehmann-Haupt, Hellmut, Peter Schoeffer of Gernsheim and Mainz, Rochester, NY: The Printing House of

Leo Hart. (1950).

Lundh 2019 Lundh, Lars-Gunnar, “The

Crisis in Psychological Science and the Need for a Person-Oriented Approach”

Social Philosophy of Science for the Social Sciences, Jaan

Valsiner (ed), Cham, Switzerland: Springer. (2019), pp. 203–224.

Mettler 2017 Mettler, Katie, “Charging Bull sculptor says Fearless Girl distorts his art, so he's fighting

back”

Chicago Tribune, April 12 (2017). Available at:

https://bit.ly/3etBGRS [Accessed 27 May

2020].

Papert 1980 Papert, Seymour, Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas, New York: Basic Books.

(1980).

Ralph 2018 Ralph, Bill, “Artist's

Statement”(2018), BillRalph.com

https://bit.ly/2YvD53D [Accessed 27 May 2020].

Ramsay 2014 Ramsay, Stephen, “The

Hermeneutics of Screwing Around; or What You Do with a Million Books”

PastPlay: Teaching and Learning History with Technology ,

Kevin Kee (ed), Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. (2014):111–120.

Rigney 2010 Rigney, Daniel The

Matthew Effect: How Advantage Begets Further Advantage, New York: Columbia

University Press. (2010).

Sinclair and Rockwell 2016 Sinclair, S. and Rockwell G.,

“Text Analysis and Visualization”

A New Companion to the Digital Humanities, Chichester, West

Sussex, UK: Wiley- Blackwell. (2016), pp. 274–290.

Teilhard de Chardin 1959 Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre,

The Phenomenon of Man, London: Collins. (1959).

Thompson 2014 Thompson, Ian H., Landscape Architecture: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press. (2014).

Waldrop 1992 Waldrop, M. Mitchell, Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order

and Chaos, New York: Simon and Schuster. (1992).

Waloszek 2003 Waloszek, Gerd, “User

Interface Design – Is it A Science, An Art, or A Craft?”

SAP Design Guild (2003). Available at: https://bit.ly/3gt1Sh3

[Accessed 27 May 2020].

Weller 2017 Weller, Richard, “Our

Time?”

The New Landscape Declaration, Gayle Berens (ed),Los Angeles,

CA: Rare Bird Books. (2017), pp. 5–12.

Wohlleben 2015 Wohlleben, Peter, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They

Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World, Trans. Jane

Billinghurst, Vancouver, Greystone Books. (2015).