Abstract

The ubiquity of the web has dramatically transformed scholarly communication.

The shift toward digital publishing has brought great advantages, including

an increased speed of knowledge dissemination and a greater uptake in open

scholarship. There is also an increasing range of scholarly material being

communicated and referenced. References have expanded beyond books and

articles to include a broad array of assets consulted or created during the

research process, such as datasets, social media content like tweets and

blogs, and digital exhibitions. There are, however, numerous challenges

posed by the transition to a constantly evolving digital scholarly

infrastructure. This paper examines one of those challenges: link rot. Link

rot is likely most familiar in the form of “404 Not Found” error

messages, but there are other less prominent obstacles to accessing web

content. Our study examines instances of link rot in Digital Humanities Quarterly articles and its impact on the

ability to access the online content referenced in these articles after

their publication.

Introduction

The ubiquity of the web has dramatically transformed scholarly communication. The

shift toward digital publishing has brought great advantages, including an

increased speed of knowledge dissemination and a greater uptake in open

scholarship. There is also an increasing range of scholarly material being

communicated and referenced. References have expanded beyond books and articles

to include a broad array of assets consulted or created during the research

process, such as datasets, social media content like tweets and blogs, and

digital exhibitions. There are, however, numerous challenges posed by the

transition to a constantly evolving digital scholarly infrastructure. This paper

examines one of those challenges: link rot, which serves as a way towards

understanding its corollary, reference rot. Link rot is likely most familiar in

the form of “404 Not Found” error messages, but there are other less prominent

obstacles to accessing web content. Our study examines instances of reference

rot in Digital Humanities Quarterly articles and its

impact on the ability to access the online content referenced in these articles

after their publication. We also look at the extent to which article references

rely on links in order to gain a more complete understanding of the threat

posed.

This study provides an important step in assessing remediative actions as well as

a broader examination of perceptions of cohesion and integrity in the digital

humanities literature. As the Endings Project team mentions in their DH2019

paper, HTML is the most popular standard output for DH projects, meaning that

websites continue to be a key mechanism for delivering digital humanities (DH)

outputs [

Arneil et al. 2019]. The ongoing costs and resources required to

maintain and repair web-based DH outputs is well known, as shown by efforts such

as the Endings Project and the Socio-Technical Sustainability Roadmap

[

Socio-Technical n.d.] [

Endings 2022]. Our research contributes to this area of

knowledge from a particular angle: the impact on the stability of the DH

scholarly record.

Literature Review

Looking at the literature, we observe three main categories relevant to this

article: theory of citation, evolving guidelines for proper citation, and

studies of the practice of link preservation. Citation theory describes the

continuous tug between the ideals of citation and the disciplinary

administrative function of scholarly discourse [

Zuckerman 1987]. Broadly

speaking, a reference is a piece of information provided in a scholarly work

that specifies the work of another person used in the creation of the former. A

citation is a paraphrase, quotation or allusion to a source, a specific instance

of a reference such as a paraphrase or quotation. The scholarly literature rests

on the premise that citations and references exist to pay homage and give credit

to prior work, to substantiate claims and maintain intellectual honesty, and to

provide leads and background reading [

Garfield 1994]. Consequently, if readers

cannot access the referenced material, then they are unable to uphold these

standards or corroborate the scholarly record. The arguments of individual

articles are weakened, and the integrity of the scholarly literature is

threatened. Recent efforts have contributed critical approaches to citation

theory, such as citation justice, that seek to expand understanding of social

systems of credit within academia [

Knowledge Equity Lab n.d.].

Hyperlinks are a critical component of scholarly discourse in the digital era, and

in the late 1990s and early 2000s, we see researchers beginning to adapt

citation guidelines to accommodate new online resources. Janice Walker created

MLA-Style Citations of Electronic Sources for referencing emerging formats such

as Telnet, listservs, and video games [

Walker 1995], whereas Anita Greenhill and

Gordon Fletcher sought to catalog citation recommendations in the World Wide Web

Virtual Library [

Greenhill 2003], and the Library of

Congress’s “Learning Page” demonstrates the concern for capturing appropriate

links. Across disciplines, citation guidelines have grown to accommodate, and

hustled to keep up with, shifts in web practices. As of the 7th edition, the APA

Handbook (

2020) offers examples for 27 types of electronic

resources, from websites to Wikipedia to datasets to podcasts. This range of

electronic resources points to the widening understanding of viable source

materials as well as the complex set of standards that authors and stewards of

scholarly output must reconcile.

In “Scholarly Context Not Found: One in Five Articles Suffers from Reference Rot,”

[

Klein et al. 2014] studied science, technology, and medicine articles to

document the extent of reference rot, which they define as a combination of link

rot and content drift. They define content drift as a resource changing or

evolving over time, up to the point where it no longer reflects the originally

referenced content. Attributing the lagging system of link preservation to the

swift adoption of web-based scholarly communications, the expanding capacity to

reference different types of things, and the challenge of bridging digital

reference systems and paper-based communications, the authors call for robust

solutions to ensure integrity of the web-based scholarly record. To Klein and

co-authors, the integrity of the link maintains the context necessary to ensure

sound scholarship, for “as references rot or as the content they originally

referred to changes, it becomes impossible to revisit the intellectual context

that surrounded the referencing article at the time of its publication” [

Klein et al. 2014].

Zhou et al.

2015 studied the persistence of web resource citations

by developing a machine-learning model for assessing link rot in scholarly

articles. They propose establishing a system of priority for archival

preservation of links by proactively predicting links more prone to rot.

[

Brunelle et al. 2015] attempt to measure the impact of missing

resources through web user experience interviews that evaluate how the loss of

embedded resources affects user trust in archived websites. The Hiberlink and

Robust Links projects have contributed valuable research framing the problem of

reference rot in the scholarly literature. While their recommendations rely on a

specific set of digital publishing tools that has not yet been widely adopted

across the academy, the project has contributed a more sophisticated

understanding of how link preservation requires attending not only to the ideals

of citation and web maintenance best practices but also to the social

expectations concerning who is responsible for these linkages [

Robustify n.d.].

Our study joins these and others that have examined instances of link rot in the

scholarly literature. Our aim here is not only to document the amount of link

rot but also to understand the extent to which citations rely on links. To do so

we also looked at the percentage of articles that contain links, the average

number of links per article, and the percentage of citations that are links.

Only two other studies to date have examined all of these topics together.

[

Aronsky et al. 2007] examines PubMed articles immediately after

publication, and [

Yang et al. 2010] provide a comprehensive study of

Chinese humanities and social science journals. Several studies examine one or

two of these topics, and are used in the Analysis section to contextualize our

data and to understand how the DH literature compares to other disciplines.

Methodology

Our study examines the prevalence of websites listed as citations in

DHQ articles and the status of those websites.

DHQ is one of the most long-standing, well known

journals within the field of digital humanities and is listed in the Directory

of Open Access Journals as well as indexed in the Clarivate Analytics “Emerging

Sources Citation Index” [

DHQ About n.d.]. All types of articles were included in

the analysis (e.g. Introductions, Articles, Reviews) as each article type

consistently contained references. Our analysis examined only citations

appearing in the Works Cited section and excluded citations in the Notes section

as well as in-text links. When analyzing an individual link, we manually opened

the link in a new browser tab, observed any changes in the URL as the page

loaded, and once the page loaded (or not) placed it into one of seven

categories. In a small number of cases, the link was correctly displayed but the

HTML code contained a minor formatting error. We chose to follow the (correctly)

displayed link, under the assumption that a reader interested in following the

citation would do the same. Beyond this, we did not perform any additional

searching to track down if a page had been relocated or archived, since the

object of study is the link as it appears in the citation. The browser

environments used for analysis were free of ad blockers and similar browser

extensions, which can significantly alter how URLs and pages perform. The

analysis was performed in the United States, and we acknowledge that results

will likely differ depending on geographic location due to Internet Protocol

(IP) address restrictions.

We examined articles published in

DHQ from its inception in

2007 up to 2019. To make the data collection process more manageable, we used

systematic sampling to determine which articles to analyze. Systematic sampling

uses a fixed interval, and fits this particular dataset because the citations

and links within the articles in

DHQ are sufficiently

normally distributed. This method ensures even representation of the

characteristics of the articles published per year that we want to observe

(i.e., number of citations, number of links and working status of the links),

which was important in allowing us to reliably track trends over time [

Hibberts et al. 2012]. Since the population size is known, we chose the sampling interval

based on our desired confidence interval, 95%, and margin of error, 5%, for the

proportion of citations that are links, assuming a variance of 25%. In order to

achieve this, the target sample size would be 205 with a sampling interval of

0.47. We rounded up the sample interval to 0.50, meaning that we analyzed every

other article (226 total), which slightly improves the margin of error to 4.55%

while maintaining the 95% confidence interval.1 We decided that defining the

population as the total number of articles, rather than total number of

citations, would better foster future re-use of the data set, which is openly

available online [

Coble & Karlin 2021].

Each citation that appeared as a link in the sample was labeled using one of seven

categories:

Link resolves correctly:

- 1. Page exists

- 2. Redirected, to the same page

Link does not resolve correctly:

- 3. Page exists, but is different

- 4. Redirected, to same site

- 5. Redirected, but page or site is different

- 6. Page does not exist, site exists

- 7. Page does not exist, site does not exist

1. Page Exists

The link resolves as expected and it resolves to a page with content that is

clearly the cited source. This category includes Handles and DOIs, paywalled

content with previews (e.g. New York Times), and pages

with SSL certificate issues that still resolve.

2. Redirected, to the same page

The link redirects automatically and takes you to a page with content that is

clearly the cited source. It is important to note that, for all categories,

determinations of whether a page is the same or different are based primarily on clues given in the

citation — most notably the page title, creator, and similar URL structure. Some

assumptions were made based on information available, and this is a potential

source of error in the study.

3. Page exists, but is different

The link resolves but the page content is obviously and significantly different

from what was cited, such as web technologies that are no longer supported by

browsers (e.g. Abode Flash).

4. Redirected, to same site

The link redirects, although the user is taken to a different page on the same

top-level domain (typically the homepage) rather than the page specified in the

citation. This outcome was common in cases where a site migration had occurred.

Though this is not the most worrisome category, since the intended page often

still exists and is findable with additional effort, technically speaking the

link does not resolve correctly.

5. Redirected, but page or site is different

Redirected to a page or site that is obviously and significantly different from

the cited source.

6. Page does not exist, site exists

The page no longer exists but the site it was part of still resolves. One

challenge with our approach of differentiating a web page and a website is

determining what exactly is the “site.” Practices can vary widely, particularly

in citations of non-academic works, and we used discretion when it was obvious

from contextual clues in the content and URL structure, otherwise we defaulted

to using the top-level domain.

7. Page does not exist, site does not exist

Neither the page nor the site it was part of still resolves. This is the most

worrying category, as there is effectively no original trace left of the cited

source. Such pages might be captured in the Internet Archive or other web

archives, but that outcome was outside the scope of this study.

Findings

| Total articles analyzed (including articles without links) |

226 |

| Total articles analyzed (only articles with links) |

180 |

| Articles in sample without any citations containing links |

46 |

| Total citations analyzed (only links) |

1,924 |

| Total citations in sample (links & non-links) |

6,934 |

Table 1.

Summary of Sampled Data

Table 1 provides general information about the sample. There were 226 total

articles in the sample. Of these, 180 articles contained links and 46 articles

did not contain any citations with links. There were 6,934 total citations in

the sample (links and non-links) and 1,924 of those citations contained

links.

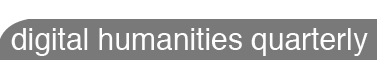

Figure 1 breaks down this information by year, where the first column (in blue)

shows the average number of total references (links and non-links) contained in

the sampled articles published that year. For instance, on average, an article

published in 2007 contains twenty-three citations, which includes both

references to print sources and links to websites. This data was collected using

web scraping and it maps onto the primary axis (i.e., the y axis on the left,

with the range 0 - 45). The second column (in yellow) shows the percentage of

citations that are links for that year. For example, for all sampled articles

published in 2007, 32% of the citations are links. Conversely, 68% of the

citations point to “non-website” sources, such as print materials, interviews,

and other types of media. This number is calculated by dividing the total number

of citations that are links by the total number of citations overall (links and

non-links), and it maps onto the secondary axis (i.e., the y axis on the right,

with the range 0% - 100%).

| Page exists |

1131 (58.8%) |

| Redirected, to the same page |

197 (10.2%) |

|

Total links that work correctly

|

1328 (69%)

|

| Page exists, but is different |

37 (1.9%) |

| Redirected, to same site |

53 (2.8%) |

| Redirected, but page or site is different |

22 (1.1%) |

| Page does not exist, site exists |

333 (17.3%) |

| Pages does not exist, site does not exist |

151 (7.8%) |

|

Total links that do not work correctly

|

596 (31%)

|

Table 2.

Totals for Link Status Categories

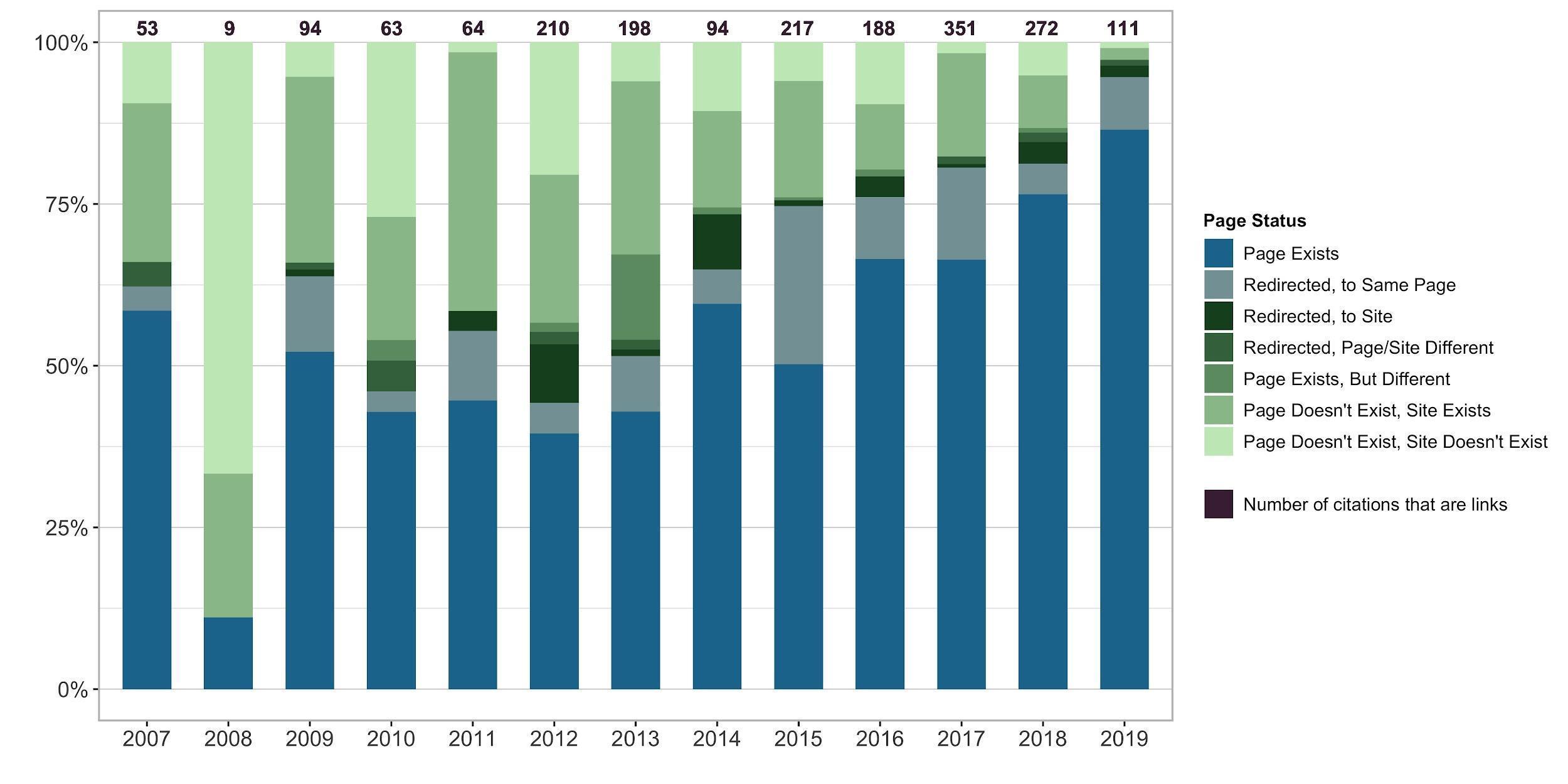

Table 2 provides totals for the link status categories analyzed in the sample.

Figure 2 visualizes this data, where each column is one year and contains the

total percentage for each category, represented by color. The total number of

sampled citations analyzed each year is given at the top of each bar. The

sections in blue represent links that work correctly (i.e., the link resolves to

the cited source). The sections in green represent links that do not work

correctly (i.e., the link does not resolve to the cited source). While the data

is not entirely uniform — for instance, there are only nine citations in the

sample for 2008 — a clear trend is observable where over time it becomes

increasingly likely that a link will not resolve correctly.

Analysis

|

Field

|

Link Source

|

Years

|

N

|

| Journalism & Communication |

URLs contained in citations in 5 journals [Dimitrova & Bugeja 2007] |

2000-2003 |

39% |

| Library & Information Science |

Online resources cited in 4 journals [Sadat-Moosavi et al. 2012] |

2005-2008 |

36% |

| Digital Humanities |

Works cited containing links in Digital Humanities

Quarterly

|

1997-2019 |

31% |

| Nursing |

Links in citations from 20 journals [Oermann et al. 2008] |

2004-2005 |

28% |

| Science, Technology, & Medicine |

URLs in references in 3 databases [Klein et al. 2014] |

1997-2012 |

13-22% |

| PubMed |

Internet references in bibliographies [Aronsky et al. 2007] |

2006 |

12% |

Table 3.

Percentage of links in citations that do not resolve

We know that link rot exists on the web, and Figure 2 demonstrates that there is

something significant at stake as it relates to the integrity of the DH

literature. Within the sample, there are 596 works cited that are links that do

not work correctly. This count means that 31% of citations containing links, and

8.7% of all sampled citations, including non-link citations, no longer work

correctly. Conversely, 69% of links still resolve to the cited source.

These numbers become more troubling when compared to other disciplines. Table 3

compares our data to other studies examining links that appear in references or

works cited section and reveals that DHQ has a comparable

and relatively high percentage of link rot. Since we looked only at the works

cited section, we excluded comparison studies that analyzed links in other

areas, such as abstracts or entire articles.

|

Field

|

Link Source

|

Years

|

N

|

| Humanities and Social Sciences |

Citation links from articles in the Chinese Social Sciences Index

[Yang et al. 2010] |

1998-2007 |

82% |

| Library & Information Science |

URLs in references from 9 journals [Veena & Sampath Kumar 2008] |

2000-2006 |

81% |

| Digital Humanities |

Works cited containing links in Digital Humanities

Quarterly

|

1997-2019 |

80% |

| Science |

Links in citations from 3 high impact journals [Dellavale et al. 2003] |

2003 |

30% |

| PubMed |

Internet references in bibliographies [Aronsky et al. 2007] |

2006 |

9% |

Table 4.

Percentage of articles that contain links

Compounding the threat of link rot is the extent to which references in the DH

literature rely on internet resources. According to sampled data, 80% of

articles in DHQ contain at least one reference with a

URL. As Table 4 indicates, this percentage is relatively high compared to other

fields where data is available. Additionally, Table 5 shows that DHQ articles contain an average of 8.5 links per

article, which is significantly higher compared to other disciplines. This

suggests that the problem of link rot is spread across a high proportion of

articles. The higher frequency of links as citations indicates a greater

reliance on links compared to other fields.

|

Field

|

Link Source

|

Years

|

N

|

| Digital Humanities |

Works cited containing links in Digital Humanities

Quarterly

|

1997-2019 |

8.5 |

| History |

Links in articles from 2 journals [Russell & Kane 2008] |

1999-2006 |

3.9 |

| Nursing |

Links in citations from 20 journals [Oermann et al. 2008] |

2004-2005 |

3.1 |

| Ecology |

Citation to material on the internet [Duda & Camp 2008] |

1997-2005 |

2.0 |

| Computer science & engineering |

Articles containing URLs in 2 journal databases [Spinellis 2003] |

1995-1999 |

1.7 |

| Humanities and Social Sciences |

Citation links from articles in the Chinese Social Sciences Index

[Yang et al. 2010] |

1998-2007 |

0.37 |

| PubMed |

Internet references in bibliographies [Aronsky et al. 2007] |

2006 |

0.18 |

Table 5.

Average number of links per article

Overall, 27% of sampled citations in DHQ are links. Table 6

shows that DHQ ranks high among studies that calculate

the percentage of citations that contain links; only library and information

science contain more (44%). This figure shows that, more than most disciplines,

the DH literature relies heavily on links.

|

Field

|

Link Source

|

Years

|

N

|

| Library & Information Science |

URLs in references from 9 journals [Veena & Sampath Kumar 2008] |

2000-2006 |

44% |

| Digital Humanities |

Works cited containing links in Digital Humanities

Quarterly

|

1997-2019 |

27% |

| Humanities and Social Sciences |

Citation links from articles in the Chinese Social Sciences Index

[Yang et al. 2010] |

1998-2007 |

3.60% |

| Science |

Links in citations from 3 high impact journals [Dellavale et al. 2003] |

2003 |

2.60% |

| PubMed |

Internet references in bibliographies [Aronsky et al. 2007] |

2006 |

0.60% |

Table 6.

Percentage of citations that are links

There are some caveats to our findings. For instance, even if a link does not

work, the page might still exist at a different link. The web is fluid, and our

study is only a snapshot of a particular moment from a particular geographic

location. Also, a broken link does not necessarily mean a non-existent page. A

simple search could reveal the new URL, a site may only be temporarily

unavailable, or it might be available in the Internet Archive or another web

archive. A study of library and information science literature found that

employing these two strategies decreased the rate of inaccessible URLs from 36%

to 5% [

Sadat-Moosavi et al. 2012].

Discussion

Our data shows that a significant number of works cited no longer exist, are

inaccessible, or have additional barriers to access. Instances of link rot

increase with time. Additionally, there is a higher frequency and higher

proportion of links contained in DHQ articles, showing

that internet resources are a critical part of the DH literature. Taken

together, the combined result is a persistent and cumulative threat to the

integrity and stability of the DH literature, and one that is even more alarming

when compared to other disciplines.

Just as there are multiple causes of link rot, there is no single or simple

solution to this threat. Here we revisit the three categories presented in the

literature review to use as a framework for discussion: theory of citation,

evolving guidelines for proper citation, and studies of the practice of link

preservation. We focus on recent initiatives as well as overlooked aspects that

we believe are worth greater attention.

The area of citation theory has much potential for reframing our understanding of

the problem. Many technical solutions have been proffered, but after almost

three decades the problem of link rot is as persistent as ever and there has not

yet emerged a convincing full-scale solution. Thus, perhaps we need new lenses

through which to view this phenomenon. For instance, it may be worth revisiting

the broad assumption that scholarly literature should be accessible for the long

term. Put differently, are there wider epistemological shifts or perceptions

toward academic systems of credit that are being reflected in our commitment to

widening the scope of verifiable sources?

In

Digital Diaspora: A Race for Cyberspace [

Everett 2009],

Anna Everett lays out the critical ways a Black digital public sphere developed

parallel to the white, masculinist domain of the early Internet. Kelly Baker

Josephs and Roopika Risam continue this thread in their introduction to

Digital Black Atlantic [

Josephs & Risam 2021] and work

to name these digital spaces of resistance. Josephs and Risam, in pursuit of the

objective “to create a provisional space and framework for academic conversation

that could emerge by virtue of acts of citational and conceptual juxtaposition,”

gesture toward alternative acts of scholarly activation. Current pedagogies of

writing also point to a shifting sense of how to cite sources. In “Web Writing

and Citation: The Authority of Communities,” [

Switaj 2015], Elizabeth Switaj

lists the variations on retweet (RT), modified tweet (MT), via, and hat-tip

(h/t) that indicate a move on social media to gestural citation, its paths to

conversation, and its social system of credit.

The second area, guidelines for citation, has the potential for incremental

improvements to the health of the scholarly record. For authors, Sadat-Moosavi et al.

2012 suggest best practices for constructing links, such as citing

documents in repositories (which typically use persistent identifiers) rather

than private for-profit platforms such as Academia.edu and ResearchGate. When

available, using persistent identifiers is a key practice. Of the 108 DOI links

in our data, 107 resolved correctly (99.1%). Some publishers use DOIs in the URL

string (e.g.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118680605.ch23) but

such links are not persistent (i.e. the persistent link is

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118680605.ch23). Seemingly minor details make a

difference, and ideally such strategies would be more widely incorporated into

citation manuals in an effort to provide authoritative guidance to

researchers.

There are a number of approaches to the third area, the practice of link

preservation. Building on Aronsky et al.

2007 finding that 12% of links in PubMed

were already broken two days after publication, journals should incorporate

link-checking as a regular part of the editorial process. Further, scanning all

article links on a regular basis would make this work more manageable for

journals and also help to identify patterns or issues specific to their field.

Another option would be to implement measures such as those of the

Review Journal of the IDE, which also requires authors

to use the Internet Archive’s “Save Page Now” service [

RIDE n.d.] for referenced

links. This helps ensure that a record exists of the site as it was originally

referenced, which Jones et al.

2021 identify as a core issue but one that is

not inherently guaranteed by web archiving services such as the Internet

Archive, Archive-It, or Conifer. The on-demand service Perma.cc was specifically

designed to address reference rot by generating permanent links to affix web

citations used in publishing [

Perma.cc n.d.]. Perma.cc comes the closest to

providing a turnkey solution, although its approach is to replace the original

resource with a replica. Each of these web archiving strategies show different

approaches that can be employed by journals, although it is worth noting that

they rely on external service providers.

Finally, there are several recent initiatives providing resources for website

creators and maintainers as well as a growing general awareness of the labor and

craft required to build and sustain web-based DH outputs. Page-level redirects,

or URL forwarding, is a proven and established technique for ensuring that links

resolve correctly, and is particularly important when migrating a site or

performing other updates that alter the URL structure of references. Best

practices for this are thoughtfully articulated in Guidelines for Preserving New

Forms of Scholarship [

Greenberg et al. 2021].

More broadly, the Socio-Technical Sustainability Roadmap gives a practical

framework and holistic approach for the range of work involved in the entire

lifecycle of a project [

Socio-Technical n.d.]. And the Endings Project has

produced a valuable set of tools, principles, and body of knowledge that

advances our ability to create “accessible, stable, long-lasting resources in

the humanities” [

Endings 2022]. Additionally, [

Minimal Computing n.d.] provides an

ethos that undergirds this work, and tools like Wax directly put these

principles into practice by generating static sites [

Minimal Computing n.d.]

[

Nyröp n.d.]. None of these will inherently ensure long-term access to websites,

and it is crucial to acknowledge that all require real and sustained

institutional investments in staff and technical resources (see the articles by

Otis and Cummings in this issue). However, there is some room for optimism given

the overlap and shared history between DH and scholarly communication [

Coble et al. 2014]. The practitioners of the latter, who share a keen interest in the

stewardship of the scholarly record and have already taken great strides to

address this phenomenon, are well positioned in terms of expertise and resources

to continue these efforts. Taken together, they constitute an engaged community

bringing necessary advancements to digital scholarly infrastructure.

Conclusion

Scholarly discourse depends on the practice of referencing sources. Our study

shows that over a quarter of sampled citations are links to websites. Over 30%

of these references are inaccessible or have additional access barriers. When

compared to other fields, articles in DHQ contain the

highest number of links per article, a high proportion of citations that are

links, and a high proportion of articles that contain links. This problem is

persistent and gets worse over time, creating a significant threat to the

stability and integrity of the DH literature.

Even when we acknowledge that link rot and content drift present a risk to the DH

literature, it is worth exploring to what extent this is a problem. It is unwise

to simply assert that all websites should be accessible forever. Rather, within

the context of scholarly literature, we should consider what criteria or

considerations would be helpful to better understand which sites require longer

term access. Preserving the record of a resource does not inherently preserve

access to that resource, and understanding the social expectations of citation

practice within a given field should be taken into account as DH citations are

created. Maintaining access to websites is different from maintaining links to

those websites, and it is always worth emphasizing that implementing such

approaches at scale requires significant investments of labor and resources from

institutional coalitions of publishers, libraries, and archives.

Notes

- Three main characteristics were observed in our analysis: number of

citations per article, percentage of citations that are links and percent

of links that work. Our sample size was chosen to ensure confidence about

the percentage of citations that were links and we observed the status of

all of those. Given the observed standard deviations of our sample

characteristics we are able to calculate the margin of error for a 95% and

a 99% confidence interval. The results are presented on the following

table:

|

|

Links per article |

Percent citations that are links |

Percent of links that work |

|

|

Mean |

8.5 |

28% |

69% |

|

|

Standard Deviation |

11.3 |

24% |

29% |

|

|

Sample size |

226 |

213* |

180** |

|

|

Population |

438 |

438 |

438 |

|

|

Margin of error (95% confidence interval) |

1.47 |

3% |

4% |

|

|

Margin of error (99% confidence interval) |

1.93 |

4% |

5% |

|

|

* For this we only consider papers that have citations |

|

|

** For this we only consider the papers where at least one citation

is a link |

|

Table 7.

Citation data statistics

Acknowledgements

The authors give thanks to Luiza Nassif Pires.

Works Cited

APA 2020 American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association 2020: the official guide to APA style (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

Arneil et al. 2019 Arneil et al. (2019) “Project Endings: Early Impressions from

Our Recent Survey On Project Longevity In DH”

DH2019, Utrecht, Netherlands.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.34894/SIKOBN.

Aronsky et al. 2007 Aronsky, D., Madani, S., Carnevale, R.

J., et al. (2007) “The prevalence and inaccessibility of

Internet references in the biomedical literature at the time of

publication”,

Journal of the American Medical

Informatics Association, 14(2), pp. 232–234. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M2243.

Brunelle et al. 2015 Brunelle, J. F., Kelly, M., SalahEldeen, H. et al. (2015) “Not all mementos are created equal: measuring the impact of missing resources”,

International Journal on Digital Libraries, 16, pp. 283–301. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-015-0150-6.

Burnhill et al. 2015 Burnhill, P., Mewissen, M., & Wincewicz, R. (2015)

“Reference rot in scholarly statement: threat and remedy”,

Insights, 28:2, 55–61. Available at:

http://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.237.

Coble et al. 2014 Coble, Z., Potvin, S., and Shirazi, R. (2014) “Process as

Product: Scholarly Communication Experiments in the Digital Humanities”,

Journal

of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 2:3. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.1137.

Dellavale et al. 2003 Dellavalle, R. P., Hester, E. J., Heilig, L. F., et al.

(2003) “Going, Going, Gone: Lost Internet References”,

Science, 302:5646,

787-788. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1088234.

Dimitrova & Bugeja 2007 Dimitrova, D. V. and Bugeja, M. (2007) “The half-life

of internet references cited in communication journals”,

New Media &

Society, 9:5, 811–826. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807081226.

Duda & Camp 2008 Duda, J. J., and Camp, R. J. (2008) “Ecology in the information

age: patterns of use and attrition rates of internet-based citations in ESA

journals, 1997–2005”,

Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 6(3), pp. 145–151.

Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1890/070022.

Everett 2009 Everett, A., (2009) Digital Diaspora. Albany, NY: State University

of New York Press.

Garfield 1994 Garfield, E. (1994) “When to Cite”, Library Quarterly,

66(4), pp. 449–58.

Greenhill 2003 Greenhill, A., and Fletcher, G. (eds.) (2003) “Electronic

References & Scholarly Citations of Internet Sources”,

The World-Wide Web

Virtual Library. Available at:

http://www.spaceless.com/WWWVL/.

Hibberts et al. 2012 Hibberts M., Burke Johnson R., and Hudson K. (2012) “Common

Survey Sampling Techniques” In L. Gideon (ed.),

Handbook of Survey Methodology

for the Social Sciences. New York, pp. 53–74. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3876-2_5.

Josephs & Risam 2021 Josephs, K. B., and Risam, R. (eds.) (2021)

Digital Black

Atlantic. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.5749/9781452965321.

Klein et al. 2014 Klein M, Van de Sompel H, Sanderson R, et al. (2014)

“Scholarly Context Not Found: One in Five Articles Suffers from Reference Rot”,

PLoS ONE 9(12), e115253. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115253.

Oermann et al. 2008 Oermann, M. H., Nordstrom, C. K., Ineson, V., and Wilmes, N. A.

(2008) “Web Citations in the Nursing Literature: How Accurate Are They?”

Journal of Professional Nursing, 24(6), pp. 347–351. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.12.004.

Perma.cc n.d. “Perma.cc”

Harvard Library Innovation Lab. Available at:

https://perma.cc/.

Russell & Kane 2008 Russell, E., & Kane, J. (2008) “The Missing Link:

Assessing the Reliability of Internet Citations in History Journals”,

Technology

and Culture, 49(2), pp. 420–429. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.0.0028.

Sadat-Moosavi et al. 2012 Sadat-Moosavi A., Isfandyari-Moghaddam A., and Tajeddini

O. (2012) “Accessibility of online resources cited in scholarly LIS journals: A

study of emerald ISI-ranked journals”, Aslib Proceedings, 64(2), pp. 178–192.

Socio-Technical n.d. Visual Media Workshop at the University of Pittsburgh. “The

Socio-Technical Sustainability Roadmap”. Available at:

http://sustainingdh.net.

Switaj 2015 Switaj, Elizabeth. (2015) “Web Writing and Citation: The Authority

of Communities” In Dougherty, J and O'Donnell T (eds.),

Web Writing: Why and How

for Liberal Arts Teaching and Learning. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press,

pp. 223–32. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv65sxgk.24.

Yang et al. 2010 Yang, S., Qiu, J. and Xiong, Z. (2010) “An Empirical Study on

the Utilization of Web Academic Resources in Humanities and Social Sciences

Based on Web Citations”,

Scientometrics, 84, pp. 1–19. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0142-7.

Zhou et al. 2015 Zhou, K, Grover, C, Klein, M, and Tobin, R. (2015) “No More

404s: Predicting Referenced Link Rot in Scholarly Articles for Pro-Active

Archiving”,

JCDL '15: Proceedings of the 15th ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, New York, pp. 233–236. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1145/2756406.2756940.

Zuckerman 1987 Zuckerman, H. (1987) “Citation analysis and the complex problem

of intellectual influence”, Scientometrics, 12(5), pp. 329–38.