Abstract

This paper uses network theory and network analysis to propose a new approach

to analyzing cross-dressing in Shakespearean drama, specifically the key

questions driving much of the scholarship on that topic in recent decades:

What kind of disruption to the social order did cross-dressing represent in

Early Modern England, and what did it mean to shift that disruption from

the street to the stage? We know that the laws and customs of the age

emphasized clothing that matched the outward appearances of people to their

places in the social order. Network analysis allows us to analyze how

characters become gendered through a non-linear, non-hierarchical lattice

of social relationships. As the characters interact and social

relationships change, the individual’s gendered subjectivity also

transforms. We find that cross-dressing protagonists propel themselves from

isolated social worlds into a complex web of relationships through

cross-dressing, and that entry into sociability follows predictable

patterns. By following those patterns, the characters combine roles--the

broker and the heroine--that are normally separate in Shakespearean comic

plots, creating a hybrid type that becomes visible through network

analysis.

Introduction

This paper uses network theory and network analysis to propose a new approach

to analyzing cross-dressing in Shakespearean drama, specifically the key

questions driving much of the scholarship on that topic in recent decades:

What kind of disruption to the social order did cross-dressing represent in

Early Modern England, and what did it mean to shift that disruption from

the street to the stage? We know that the laws and customs of the age

emphasized clothing that matched the outward appearances of people to their

places in the social order. A letter from John Chamberlain dated 1620

exhibits the Jacobean stakes of conventionally gendered dress:

Yesterday the bishop of London called together all

his clergie about this towne, and told them he had expresse

commandment from the King to will them to inveigh vehemently

against the insolencie of our women, and theyre wearing of brode

brimed hats, pointed dublets, theyre haire cut short or

shorne...the truth is the world is very much out of order.

As Mary Beth Rose points out, the King’s commandment

“amounted to a declaration of war,” and the

results of that declaration revealed that “women in

men’s clothing had assumed threatening enough proportions in the

conservative mind to be singled out in a conscientious and thorough

attempt to eliminate the style from social life”

[

Rose 1988, 70].

The conservatives of the time attempted, in other words, to enact the kind of

restoration of propriety that Stephen Greenblatt perceives at the end of

Shakespeare’s

Twelfth Night, in which “[t]he sexes are sorted out, correctly paired, and

dismissed to bliss — or will be as soon as Viola changes her

clothes”

[

Greenblatt 1988, 71]. Indeed, one way to view much of

the cross-dressing in Early Modern drama is to see it as a fundamentally

conservative set of practices. From this perspective, cross-dressing allows

actors and their audiences the pleasure of seeing binary, hierarchical

gender relationships troubled temporarily, and not too much. Jean E. Howard

maintains that female cross-dressers retain their “properly feminine subjectivity” even while dressed as men [

Howard 1998, 432]. The heroines are then comfortably

restored to women’s status in a conception of gender that remains, in

Greenblatt’s phrase, “teleologically male”

[

Greenblatt 1988, 88].

Other scholars emphasize the extent to which cross-dressing fundamentally

troubled conventional gender roles, especially in a theatrical world that

involved all-male acting companies. As Phyllis Rackin puts it, the “boy actress's body was male, while the character he

portrayed was female. Thus inverting the offstage associations, stage

illusion radically subverted the gender divisions of the Elizabethan

world”

[

Rackin 1987, 38]. Marjorie Garber has reinforced this

sense of radical subversion in arguing that cross-dressing historically

signaled a “category crisis” for the very

concept of gender [

Garber 1997, 17]. Rackin and Garber

present a disruptive potential of cross-dressing analogous — in this narrow

way — to what Judith Butler identifies in the later phenomenon of drag:

“In the place of the law of heterosexual

coherence, we see sex and gender denaturalized by means of a

performance which avows their distinctness and dramatizes the cultural

mechanism of their fabricated unity”

[

Butler 1990, 137–8].

In the context of Renaissance drama, the perceptions of cross-dressing as

fundamentally conservative or disruptive, as opposed as they seem, share a

good deal of common ground. Both views see the potential disruption arising

from all-male casting and the ways in which female characters cross

boundaries while dressed as men, for example. Much of the disagreement

arises from different assessments of the power of comic resolutions to

contain that disruption. When the structure of comedy involves a movement

from disruption to resolution, the difference between disruptive radicalism

and reactionary essentialism can amount to a question of emphasis. Can the

resolution contain the disruption? How much of the conventional hierarchy

does a play restore when nominally female characters assume the clothing,

legal status, and dispossessions of wives in patriarchal marriage?

This paper seeks, if not to break that impasse, at least to shift the terms

of the conversation away from the linear placement of Early Modern

theatrical cross-dressing on a scale from radical disruption to the

conservative reinforcement of norms. Network analysis allows us to analyze

how characters become gendered through a non-linear, non-hierarchical

lattice of social relationships. As the characters interact and social

relationships change, the individual’s gendered subjectivity also

transforms. We find that cross-dressing protagonists propel themselves from

isolated social worlds into a complex web of relationships through

cross-dressing, and that entry into sociability follows predictable

patterns. By following those patterns, the characters combine roles — the

broker and the heroine — that are normally separate in Shakespearean comic

plots, creating a hybrid type that becomes visible through network

analysis.

This paper seeks, if not to break the impasse, at least to shift the terms of

the conversation away from the linear placement of Early Modern theatrical

cross-dressing on a scale from radical disruption to the conservative

reinforcement of norms. Network analysis allows us to analyze how

characters become gendered through a non-linear, non-hierarchical lattice

of social relationships. As the characters interact and social

relationships change, the individual’s gendered subjectivity also

transforms. We find that cross-dressing protagonists propel themselves from

isolated social worlds into a complex web of relationships through

cross-dressing, and that entry into sociability follows predictable

patterns. By following those patterns, the characters combine roles — the

broker and the heroine — that are normally separate in Shakespearean comic

plots, creating a hybrid type that becomes visible through network

analysis.

Network Analysis Methods

To perform our analysis, we generated network visualizations of each of

Shakespeare’s plays including a crossdressing heroine using the Python

library NetworkX. These visualizations, hosted at

https://rnlp.net/shakespeare/, depict the relationships among

characters scene-by-scene, shown as networks of nodes with edges connecting

them. Across the play’s scenes, each node represents a single character and

the edges linking nodes represent verbal interactions between the

characters. Edge length represents the frequency of interactions between

characters; i.e., characters that speak more lines to each other more

frequently have shorter edges between them. Node size corresponds to the

number of lines spoken by a given character in the play or scene in

question. This means that the more lines a character utters, the larger the

radius of their respective node is. For example, if we were interested in

analyzing the visualization for Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5 (fig. X), we see

there are four nodes, one each for Hamlet, Ghost, Horatio, and Marcellus.

Hamlet and the Ghost’s nodes are considerably larger than Horatio or

Marcellus’s because Hamlet and the Ghost speak far more lines than either

of the other two characters in the scene. Edges connect those characters

that speak to one another; i.e. Hamlet is linked to Ghost, Horatio, and

Marcellus, because he speaks to all of them while Ghost is linked only to

Hamlet because he speaks to Hamlet and only Hamlet.

We modeled our uses of NetworkX to measure and parse speaking relationships

among Shakespeare characters after those expressed in

Lee (2017). As such, rather than merely count

exchanges between characters to create a simple character map, our

visualizations include weighted relationships based on volume as well as

frequency of speech — that is, we assign greater importance to longer

utterances — ensuring a more comprehensive view of Shakespeare’s language

than was typical before 2017. Building upon former methods, we also

measured relationships using other social network analysis metrics to

analyze our results [

Wasserman and Faust 1994]. These included

comparative degree counts (the number of edges connected to each node),

density (the overall ratio of edges to nodes), and clustering (the

probability of two nodes being connected if they are both connected to a

third node). We display these metrics as graphs where applicable throughout

the paper.

Network visualizations have proven useful in many academic disciplines in

recent years because they rearrange linear data in a two-dimensional space,

foregrounding formerly latent connections as a visible structure. In

literary studies and other areas of the humanities, where our data (usually

language) is primarily observed one-dimensionally (through reading), it can

be difficult to accurately observe trends and large scale relationships,

let alone reenvision primary sources among so many other competing ideas in

the academy. This is especially pertinent to scholars interested in

analyzing source data in widely read and written about subdisciplines like

Shakespeare Studies. It is our assertion that network visualizations are

one way to engage with Shakespeare Studies and Queer Theory in an

innovative way while also remaining true to the text.

In another sense, reading Shakespeare as a series of networks also serves to

circumvent presupposed organizing forms among characters. Because our

networks are spatially arranged by machine, these visualizations represent

the relationships among characters based only on the amount and

directionality of their language. This means that relationships in the

network are independent of qualitative taxonomies like social hierarchy,

marriage, friendship, or employment [

Lee and Lee 2017, 12].

Instead, our networks prioritize actual acts of speech to define

relationships, away from any occlusion from paratextual descriptions

provided in the list of characters or the implications of a name. For

example, in

As You Like It, while Touchstone

does appear as a relative “touchstone” between characters in the

networks, he is mathematically displayed as such neither because of his

position as the fool, nor because of his apt name, but simply because of

how much and to how many people he speaks. From there, we might enrich our

reading of Touchstone with the qualitative facts of his character, but they

do not inform the network at the generative end. This revisioning of

Shakespeare’s plays as two-dimensional relative spaces based on direction

and amount of speech was pivotal to our analysis because it shifts focus

away from conventional organizing structures that we may take for granted

and onto how characters actually function in the text itself.

While this project began with a general interest in the ways in which

cross-dressed heroines are relationally positioned in Shakespeare’s

gender-bending plays, our research did not initially start with a

hypothesis or set of assumptions that we hoped to evidence with these

network diagrams. Rather, we used the network visualizations as a way to

perform exploratory data analysis of Shakespeare’s comedies in a different

light. Ultimately, our findings confirmed to a certain extent existing

understandings of the texts, as well as some conclusions drawn by other

scholars interested in this area. We viewed such confirmation as valuable

because it reinforced existing qualitative interpretations with a different

mode of evidence gleaned from an independent method - network analysis

rather than reading. Often however, as we will demonstrate in the following

sections, our findings complicate, and at times challenge previous

scholarly interpretations of Shakespeare’s comedies.

Embedding within the Social

Shakespeare’s comedies have been defined by “inversions

of the norms of behavior,” which can temporarily provide “the exhilarating sense of freedom which transgression

affords”

[

Gay 2002, 2]. This line of reading relies on a

definition of Bakhtin's carnivalesque from C.L. Barber, who famously

posited that Shakespeare’s comedies hinged on a movement from release to

clarification - from releasing vital energy normally “locked up in awe and respect,” to a “heightened awareness of the relation between man and nature”

[

Barber 2011, 6]. In Barber’s line of reading, the

playful transgressions of the comedy unlock social energy by functioning as

a sort of pressure valve.

Criticism on the comedies has more recently moved away from the binary poles

of order and its inversion within the play’s plot, toward a more

historically nuanced understanding of cross-dressing on the stage as a

disruptive failure of gender representation. Specifically, Tracey Sedinger

has suggested that cross-dressing on stage in the early modern context

rejects a definition of sexuality in relation to embodiment or any object

[

Sedinger 1997]. Rather, the logic of cross-dressing in

the comedies is a sequence with a specific narrative temporality. Our

analysis supports this interpretation of cross-dressing by Shakespeare’s

characters as a generative sequence or process resituating the gendered

subject within the play’s social network, as opposed to a transgression in

relation to a normative social equilibrium. In our network analysis, the

act of cross-dressing by female characters does not cut against the grain

of the normative social structure so much as it reconfigures the contours

of the structure itself.

Our network visualizations show that when female characters don men’s

clothing, the social network constructed between characters changes. The

individual characters are thrust into dynamic webs of interactions, but

more generally we see the proliferation of dense and tightly clustered

communities. Those communities allow the protagonists to meet a variety of

characters and ultimately participate in a social world that is at once

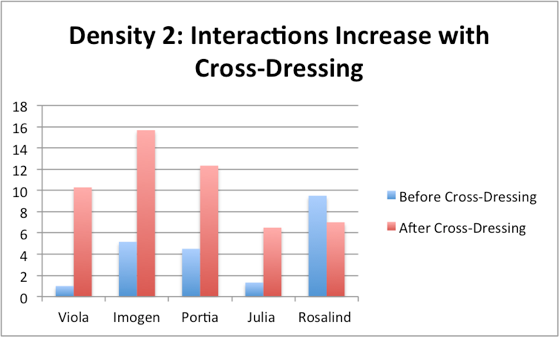

larger and more complex. Density, which measures how many interactions each

character has with the other characters in the scene, increases

significantly after the female protagonist cross-dresses. The simple bar

graph in Figure 1 shows the typical jump in density of interactions once

the protagonist cross-dresses.

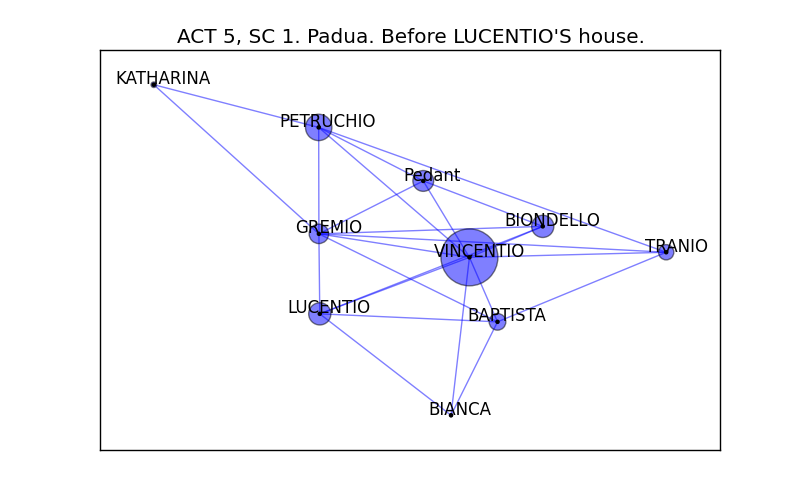

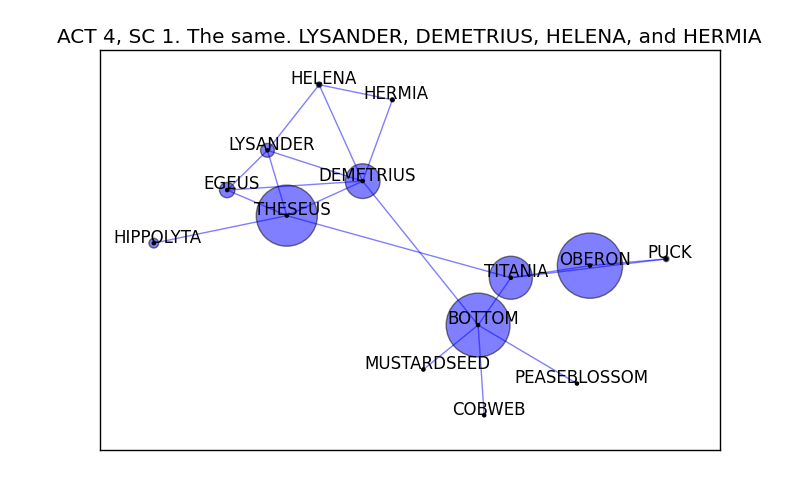

Figure 2 visualizes the interactions in each play that create the tendencies

summarized in Figure 1. In Figure 2, for each play, we visualize four

scenes from each play, in chronological sequence. In each case, the first

scene (shown at the top of the four-scene sequence) takes place before the

moment of cross-dressing, and the other three afterwards. These are only

selected scenes, but they illustrate the kinds of increasing density of

social networks that create the overall effects captured in our analysis.

Looking at these patterns across the five plays, we see visual patterns

emerging. The networks before cross-dressing are frequently structured like

a barbell or a hub and spoke; the secondary characters are companions to

the protagonists and do not interact with anyone but their masters and

mistresses. That is, the networks cluster tightly around the major

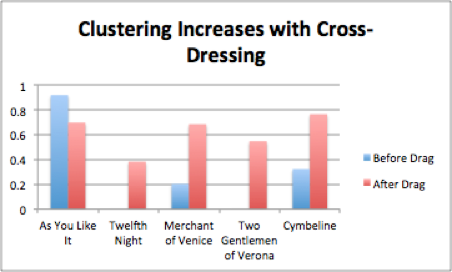

characters, who are isolated from one another. By contrast, when dressed as

men, the female characters are able to join tightly bound networks in which

many characters interact with each other. The high interconnectedness of

these groups can also be measured by the clustering coefficient of these

network, which increases in the plays after the female characters dress as

men.

Clustering can be explained with the following example: if Viola knows Olivia

and Olivia knows Sir Toby, then the likelihood that Viola and Sir Toby also

interact is high. These complex social circles expand to include characters

of different classes and professions: Julia is captured by outlaws,

Rosalind barters with a shepherd, Portia dresses as a doctor of law and

orchestrates a court scene, and Imogen befriends both shepherds and Roman

soldiers. Thus dressing as men allows these women to escape the confines of

these dialogues and participate with a larger community. Through escaping

their isolation the female characters are therefore embedded in the larger

network and able to become participants in the social drama of the

plays.

The exception to this trend is Rosalind from

As You Like

It, whose density and clustering measurements decrease after

cross-dressing and assuming the guise of Ganymede. The playtext, however,

gives us some indication of why this discrepancy occurs. Rosalind

aggressively stretches the limits of her gender play as Ganymede, by

staging a metatheatrical courtship scenario with the lovesick Orlando, in

which Ganymede plays the role of Rosalind:

I would cure you if you

would but call me Rosalind and come every day to

my cote and woo me.

(3.3.433-435)

In effect, Rosalind performs a

double move, by initially adopting the male role of Ganymede, and then by

performing the role of his object of desire, Rosalind. This complex

layering of Rosalind’s gender play based on her adoption of a female role

when in male disguise, allows her to play with the gendered courtship

behaviors shaping the encounters in the forest of Arden by switching

between object, subject, and ultimately the end of the play, the mediator

of desire. Rosalind’s oscillation between male and female identities may

account for this specific play’s density and clustering measurements.

These networks suggest that that all five of the cross-dressing protagonists

experience a change in sociality: when they put on men’s clothing they are

no longer limited to one-on-one dialogues, but instead enter into a dense

and interwoven community that allows for the drama to unfold. King James I

recognized these effects that cross-dressing could have on the larger

society when he expressed his fear that cross-dressing would create a

“world very much out of order.” However,

Shakespeare paints a different picture of its influence: rather than

creating chaos, cross-dressing transforms a sparse and isolated world into

one that multiplies social interactions.

Brokerage: The Individual within the Network

Drawing on theory of corporate organizations, Richard Jean So and Hoyt Long

argue for the importance of brokerage functions in networks: when a network

has two subgroups divided by a gap, the “broker” fills the hole in the

network and thereby enables connections among the other people who had been

separated [

So and Long 2013, 162]. So and Long draw on the work

of Ronald Burt, who writes, “A structural hole is a

potentially valuable context for action, brokerage is the action of

coordinating across the hole with bridges between people on opposite

sides of the hole, and network entrepreneurs, or brokers, are the

people who build the bridges”

[

Burt 2005, 18]. We find this concept of brokerage

useful for describing the implications of our analysis. As the female

protagonists move into the denser networks they inhabit while dressed as

men, they enable the comic resolutions of their plays by connecting

communities that begin the plays as separate social worlds.

On this point, the finding of the network analysis is intuitive and

consistent with textual evidence from the plays. For example, in

As You Like It, Rosalind leads Touchstone and

Celia into the forest, where the group meets the shepherd Corin. Although

Touchstone tries to assume the typical male role and parlay with the

shepherd, Rosalind hushes him and then bargains:

Buy thou the cottage, pasture, and the flock,

And thou shalt have to pay for it of us

(II. V.95-96)

In this exchange, Rosalind

orchestrates a business deal between Corin and the party or “us” that

Rosalind represents. Rosalind likewise manages Silvius and Phoebe’s

relationship: “Cry the man mercy, love him...so take

her to thee shepherd” (V.V.491). Here, Rosalind addresses one

party, then the other, ultimately joining the couple together. In

Cymbeline, Lucius entreats Imogen to speak for

him: “I do bid thee beg my life, good lad” (V.V.

490). When she complies, Imogen acts as a bridge between Lucius and

Cymbeline. Likewise, in

The Two Gentlemen of

Verona, Julia acts as an ironic go-between to profess Proteus’

love to Silvia: “And now am I, unhappy

messenger” (V.V. 116). And in

Twelfth

Night, Viola acts as a bridge between Orsino and Olivia:

“All the occurrence of my fortune since/ Hath been

between this lady and this lord” (V.I. 270-271). When the

visual networks show that the cross-dressers are brokers, they therefore

highlight a role that was already embedded in the text.

The less intuitive aspect of this brokerage function lies in the brokers’

centrality to their respective plays. The broker is more typically a

marginal figure whose importance lies in creating connections whose

importance outweighs the broker’s own. As So and Long put it, “One’s eyes naturally focus upon the massive ‘sun’

or smaller ‘stars’ that occupy our network visualizations, yet

somewhat less visible broker figures significantly populate the

literary field”

[

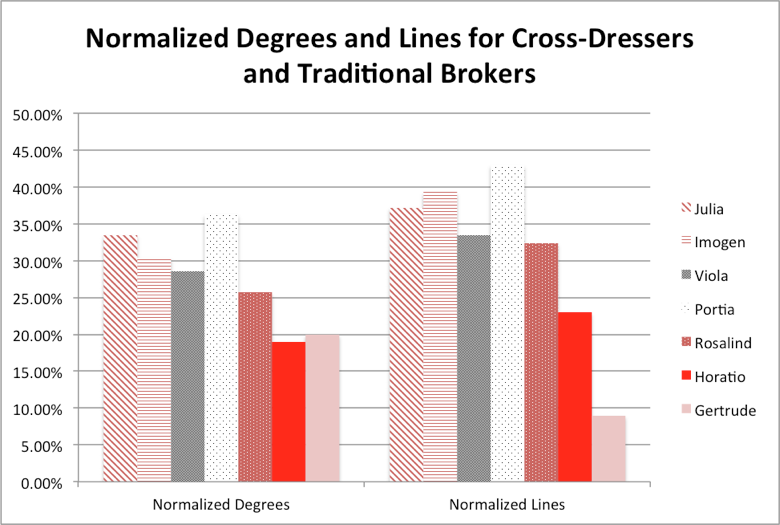

So and Long 2013, 163]. This model accurately describes the

function of Shakespeare’s more typical brokers, such as Horatio and

Gertrude in

Hamlet, who do not cross-dress. As

we can see Figure 4, the cross-dressers speak more and form more

connections — measured by degrees, or the number of links to other nodes

from each character — than do Gertrude and Horatio.

In this visualization, to compare the degrees and lines across plays, the

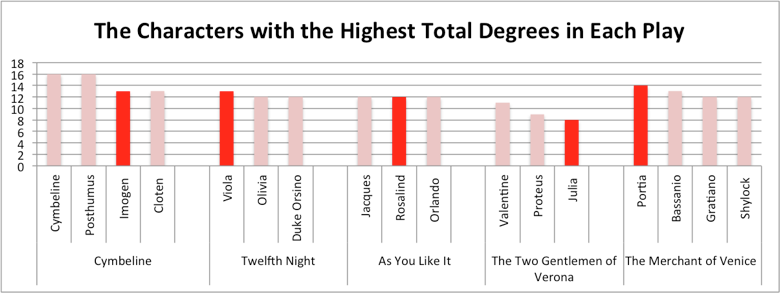

numbers are represented as a percentage of the total degrees and lines of

each play. Within a given play, we can use the unadjusted number of degrees

to illustrate the connectedness of the characters relative to one another,

as shown in Figure 5.

All of the cross-dressing protagonists are among the three most connected

characters (in Imogen’s case, tied for third) in their respective plays. In

Figure 6, network visualizations of scenes illustrate the connections that

constitute each protagonist’s network.

In the network of each play, the most connected characters have the smallest

distances to other characters; put more technically, they minimize the sum

of all distances to all other vertices. In the visualizations, therefore,

the nodes of the most connected characters appear tightly clustered with

the nodes of other characters.

We can take this line of thinking an important step further: not only do the

cross-dressing characters combines the roles of heroine and broker, but in

doing so, they also assume a dramatic centrality beyond that of their

counterparts in other Shakespearean comedies. Compare the networks formed

by cross-dressing heroines, for example, to the position of the main female

characters in two late scenes from comedies without cross-dressing

characters, Taming of the Shrew and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

In both of these networks, non-cross-dressing female characters (Katharina,

Bianca, Helena, Hermia, and Hippolyta) occupy positions at the margins of

the networks. Cross-dressing female protagonists consistently gain a

central position in the social networks involved in the final moves of the

plays. Female characters who retain conventional dress and gender

conventions, on the contrary, occupy a marginal social position during

crucial scenes of narrative resolution.

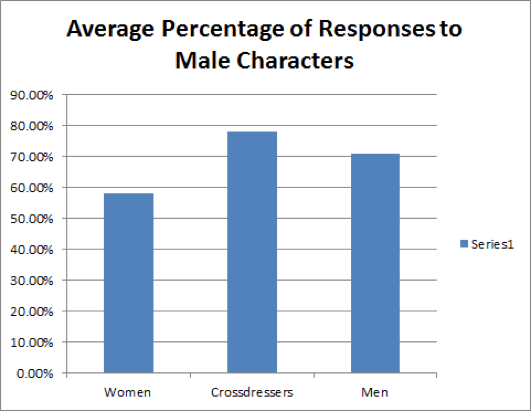

Implications for Network Structure and Gender

Considering a cross-dressed heroine in terms of networked sociability helps

us see that character’s gender in terms of relation as well as identity:

the cross-dressing not only allows a character initially gendered female to

act like a man, so to speak, but it also allows her to connect like a man.

The social worlds of all of these plays are male-dominated, in that

characters of all genders speak primarily in response to men, but we find,

in the data as well as intuitively, that male characters respond to men

more than female characters do, reflecting the plays’ tendency to

incorporate same-gender and well as mixed-gender conversations. The

cross-dressed heroines, however, respond to male characters even more than

other male characters do. As Figure 8 illustrates, when wearing men’s

clothing, the heroines inhabit the social relations of men (or even

statistical super-men), even to the point of leaving behind the

conversational connections to other women that have previously defined

their relationships.

These visualizations share a common assumption: that gender in the plays

arises initially from the categorizations that the text offers us and,

subsequently but crucially, from the nature of the characters’

interactions. In this latter aspect, gender is fundamentally relational. In

a more conventional linear model of gender, masculinity and femininity

constitute two poles, and the focus of analysis is an individual character

using cross-dressing to traverse the distance between those poles. Rather

than investigating the gender identity of isolated characters — no matter

how complex those identities may be — our approach instead describes the

social relations within dynamic systems that produce the performed effects

of gender in the plays.

The grounding of our approach in textual rather than contextual data creates

our focus on the carnivalesque effects of cross-dressing within the action

of the plays. We do not mean, however, to minimize the importance of other

approaches: for instance, Rackin’s helpful insistence on the gendering of

the actors in all-male performances of the plays implies another kind of

network visualization, showing every interaction as a male actor (in both

senses) speaking exclusively to other male actors, with our conception of

mixed-gender networks operating in ironic tension with that all-male

theatrical world. And that is not to mention yet another layer of

complication: that the “male” actors of those companies may also have

experienced their gender as relational or non-binary, thus implying in

their irrecoverable subjectivities another kind of multiply

gendered network functioning in any given performance.

In closing, we step back from the landscape of nodes and edges to consider

the implications of our analysis for reading passages of these plays in

light of a networked conception of gender. Jean Howard has made the case

that the cross-dressing heroines fail to disrupt gender relations

fundamentally because the cross-dressing women are reabsorbed into the

conventional social world by the end of of the plays. Howard argues that in

the conclusion of

Twelfth Night, for instance,

“real threats are removed and both difference and

gender hierarchy reinscribe”

[

Howard 1998, 35]. While Howard concedes that

As You Like It

“shows a woman manipulating [gender] representations in

her own interest,” Howard still maintains that the play

ultimately has the “primary effect...of confirming the

gender system”

[

Howard 1998, 37, 36]. However, in the midst of her

argument, Howard does note that this recuperation of the gendered subject

in the social world “is never perfectly

achieved”

[

Howard 1998, 41].

Howard’s reading persuasively accounts for the conservative movement of these

comic plots as well as the disruptive and incompletely contained

undercurrents that cross-dressing creates. We perceive another reading that

moves away from the conservative/radical opposition at the heart of that

reading. In

Twelfth Night, Viola initially

voices her desire to escape the bounds of society and create her own

agency:

O, that I served that lady,

And might not be delivered to the world

Till I had made mine own occasion.

(I. II. 43-45)

Here, Viola eschews typical

feminine passivity and fantasizes that she will enter the social world once

she has “made” her own place within it. Viola’s efforts, however, lead her

not to independence but entanglement, as with the lives of Orsino and

Olivia:

O Time, thou must untangle this, not I.

It is too hard a knot for me t’ untie.

(II.III.40-41)

In this moment, Viola states

that she cannot individually control the “knot” of society, even

though she may shape it through her decisions.

Viola thereafter voices a new understanding of her agency that is contingent

on her social circumstances:

Do not embrace me

till each circumstance

Of place, time, fortune, do cohere and jump

That I am

Viola;

(V.I.263-265)

Here, Viola

recognizes that she cannot entirely “make her own

occasion.” Even her most fundamental statement of named

identity, “I am Viola,” becomes a dependent

clause that is shaped by the space she inhabits, namely, the “place”

as well as the “time” and “fortune” of her circumstances.

Furthermore, all of those contingencies build on the fundamental irony of

acting, that the pleasure of watching the play involves understanding that,

in voice and body, Viola is not Viola at all.

We propose that network analysis allows new and complementary understandings

of the kinds of identity and contingency, being and relationship, that

enable performed gender to make, and be made by, its own occasions. Our

visualization of these Shakespearean networks illustrates cross-dressing

not as an individual character’s movement a simple spectrum of more or less

disruptive gender performance, but rather as an act of social

reconfiguration made more visible by visualization methods such as social

network analysis. By cross-dressing, the heroine moves to the center of a

complex social world and brokers its transformations during the part of the

play in which she dresses as a man. Even after she changes back into a

woman’s clothing, in a seemingly dismaying regression back to the governing

social norms that James I’s “commandant” sought to preserve, the

play’s resolution comes about subtly in response to her more fundamental

remaking of its networked communities.

Works Cited

Barber 2011 Barber, Cesar Lombardi. Shakespeare's festive comedy: A study of dramatic form

and its relation to social custom. Princeton University Press,

Princeton (2011).

Burt 2005 Burt, Ronald. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital.

Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005).

Butler 1990 Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of

Identity. Routledge, New York (1990).

Folger 2019 Folger Shakespeare Library. “Shakespeare's Plays from Folger Digital Texts.”

Ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Folger

Shakespeare Library,

www.folgerdigitaltexts.org, (2019).

Garber 1997 Garber, Marjorie. Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural

Anxiety. Routledge, London (1997).

Gay 2002 Gay, Penny. “As she

likes it: Shakespeare's unruly women.” Routledge, London

(2002).

Greenblatt 1988 Greenblatt, Stephen.

Shakespearean Negotiations. University of

California Press, Berkeley (1988).

Howard 1998 Howard, Jean. “Crossdressing, The Theatre, and Gender Struggle in Early Modern

England,”

Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 4

(1988).

Lee and Lee 2017 Lee, James, and Lee, Jason.

“Shakespeare’s Tragic Social Network; or Why All

the World’s a Stage,”

DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11, no. 2

(2017).

Rackin 1987 Rackin, Phyllis. “Androgyny, Mimesis, and the Marriage of the Boy Heroine

on the English Renaissance Stage,”

PMLA, 102, no. 1 (1987).

Rose 1988 Rose, Mary Beth. The Expense of Spirit: Love and Sexuality in English Renaissance

Drama. Cornell University Press, Ithaca (1988).

Sedinger 1997 Sedinger, Tracey. “‘If Sight and Shape be True’: The Epistemology of

Crossdressing on the London Stage,”

Shakespeare Quarterly, 48, No. 1

(1997).

So and Long 2013 So, Richard Jean and Hoyt Long.

“Network Analysis and the Sociology of

Modernism,”

boundary 2, 40, no. 2 (2013).

Wasserman and Faust 1994 Wasserman, Stanley

and Katherine Faust. Social Network Analysis: Methods

and Applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

(1994).

.png)