DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly

2022

Volume 16 Number 2

Volume 16 Number 2

Worlds and Readers: Augmented Reality in Modern Polaxis

Abstract

This article presents a close reading of the augmented reality (AR) comic Modern Polaxis, which was created by Stuart Campbell. Possible Worlds Theory was applied to discuss how fiction, which creates its own possible worlds, integrates the additional layer(s) of AR into its storyworld. The analysis additionally sheds light on the reader’s position and how the augmented layer may affect the literary experience. We also discuss how the AR interface may contribute to digital literature more generally.

Augmented reality (AR) came to life for everyday users of digital technology when the

game Pokémon Go took everyone to the streets with their

small screens; users discovered a fictional world that could only be accessed

digitally while blending with the surrounding real-life environment. In this article,

we explore the alignment of worlds with different ontological statuses through

digital blending in narrative fiction.

AR can be defined as a system that “supplements the real world

with virtual (computer-generated) objects that appear to coexist in the same space

as the real world”

[Azuma et al. 2001, 34]. Used as a resource in digital literature, the

real-world element may be a physical object or analogue medium that works with

digital media to produce an enhanced version of a story. Hence, in this fictional use

of AR, questions arise about the relationship between “real” and “virtual”

worlds.

In the specific case of AR comics, our question is what adding an augmented layer does to the reading experience. According to Scott McCloud the comics medium is characterised by two formal features: The blending of words and images, and the sequential reading where panels and gutters offer a participatory reading experience for the reader to fill in the blanks between the panels [McCloud 1993]. Jason Helms refers to these characteristics and states that the examples of AR comics he has seen so far “do not substantially augment the reading experience,” either because they only enhance certain images, and not the storyworld as such, or because they disturb the sequential flow of reading. However, he sees some possibilities, requiring that the AR layer was created hand-in-hand with the comic book, and that the reading experience would be better integrated [Helms 2017, 61].

For this article, we apply Possible World Theory to discuss how fiction, which

creates its own possible world [Ryan 2019, 63], integrates the

additional layer(s) of AR into its storyworld. We analyse the AR comic book Modern Polaxis to explore how AR may contribute to a complex

storyworld with several layers. We have a particular interest in how storytelling

with digital media plays with story space across media and worlds and how this may

affect a reader’s literary experience.

AR literature

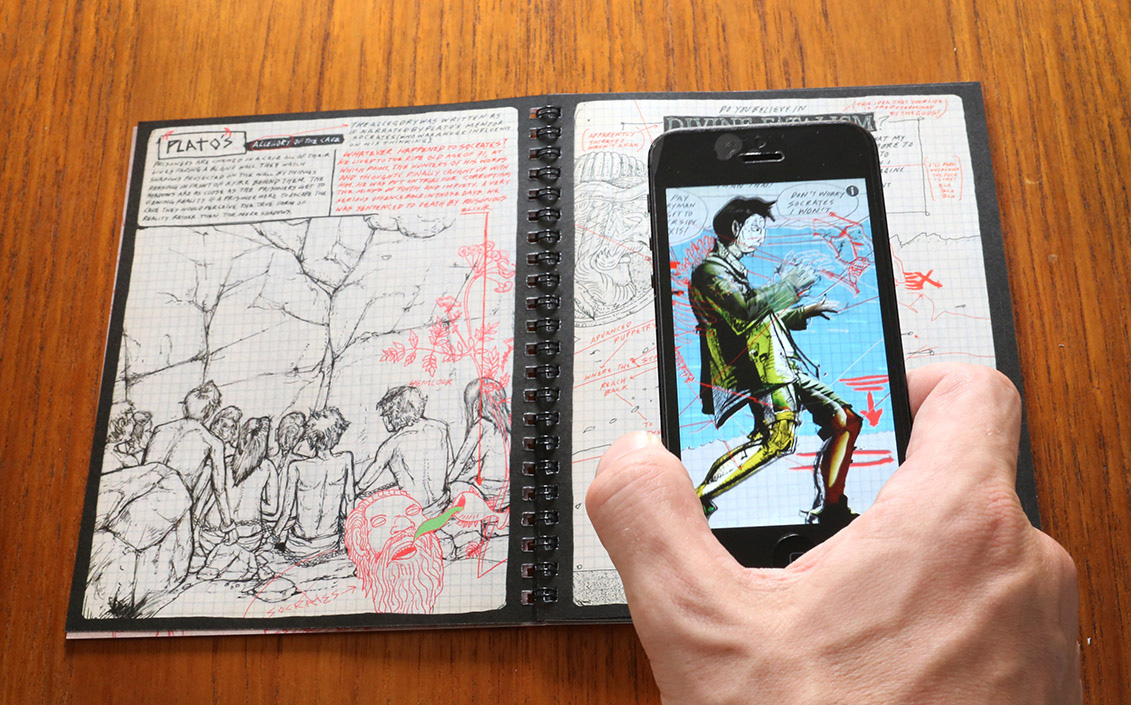

The AR comic Modern Polaxis

[Campbell 2014a] consists of a physical book and an accompanying phone

app that supplements and changes the appearance of the book’s pages (see Figure 1).

We chose this work to study how AR functions in narrative fiction, because the app

consistently adds a layer throughout the comic book, as Helms [Helms 2017] suggested. AR literature is still in its becoming, and few

examples of narrative works take advantage of AR in creative ways. A variety of

combinations of the virtual and what appears as “real” in some sense may be

envisioned. After concluding our analysis, we return to a discussion of how our

findings may be relevant to AR storytelling.

Other examples of AR in digital literature include 57°

North

[Mighty Coconut 2017], which requires a different physical object than a

book to come to life. This app is combined with a Merge Cube onto which the story is

projected. Different turns in the story are chosen by tilting the cube. The potential

for using AR with physical objects seems extensive; however, in this story, its use

is very limited. An AR comic project, Neon Wasteland

[Shields 2020] was planned to launch in summer 2021; however, at this

stage, only poster-like examples on the Neon Wasteland

website that work with the app are available for download. There are examples of AR

studios, such as BlippAR [BlippAR 2011], making commercial AR campaigns

and offering tools for AR development. They also provide an AR browser that, for

instance, works with award-winning Indian Priya comics

[Devineni et al.], which are about a female superhero. In these

comics, the app makes interactive elements pop out of the pages including animation,

films, etc., along with additional features such as AR puzzles. The subjects of the

Priya comics have transparent educational or moral

aims; for example, the latest release, Priya’s Mask

[Prakash et al. 2020], is about stopping the spread of COVID-19. Wonderscope [Wonderscope 2019] is an app that

presents stories to young children. The characters of the stories merge with the

users’ physical space. Each story is tagged with the stories’ themes (such as

confidence, respect and inclusion) or with facts the user may learn about (e.g.,

solar science or fun facts). These examples show some of AR storytelling’s diversity

and illustrate that AR has not yet established steady forms and conventions in

literary genres.

In AR literature we see a potential for combining a multitude of worlds within one

storyworld. In the analysis of Modern Polaxis, we

explore the relationship between worlds and how these may affect the reader’s

aesthetic (literary) experience. Even considering the other AR works mentioned,

Modern Polaxis is a pioneer in AR storytelling, as it

is one of the first AR comics of its kind. Moreover, it is an independent

(crowdfunded) project exploring new possibilities of AR storytelling. It entails a

very complex story, requiring an experienced reader of multimodal texts, and

thematises complicated issues, such as ontology and psychiatry. Additionally, its

aesthetic aims make it an interesting object for literary analysis.

Previous research on AR narratives

Research on AR apps has revolved around apps designed for learning, or games such as

Pokémon Go, whereas studies on AR’s potential

literary contributions are lacking. Several studies have drawn attention to

children’s AR apps and educational settings (see, e.g., [Li et al. 2017];

[Yilmaz et al. 2017]; [ChanLin 2018]; [Wu et al. 2013]; [Green et al. 2019]), while fewer studies have

addressed AR apps aimed at a wider audience that includes teenagers and adults.

Gunnar Liestøl ([Liestøl 2011]; [Liestøl 2019]) explored

AR technologies’ narrative and rhetorical potential in the context of reconstructing

historical events on location. This location perspective is a common concern in AR,

along with an image or text as the base for the AR layer [Li et al. 2017, 621]. The connection to the user’s physical location is also central to

Anders Sundnes Løvlie’s project textopia, which explored

the relations between places and literary texts. The locative system allows a user to

listen to texts relevant to the place where they are positioned. Løvlie [Løvlie 2009] analysed literary strategies that allow readers and writers

to connect literature to their lived environment. With Modern

Polaxis, what is of interest is the tension between the analogue medium of

the book and the digital layer added by the AR app, not the place in which the reader

opens the book.

Weedon et al. [Weedon et al. 2014] described an AR project called Sherwood Rise, which revealed interesting possible effects

of AR that can also be relevant to the analysis of Modern

Polaxis. Weedon et al. see AR as a possibility to disguise and hide

narratives and describe them as a way to “signal the unexpected

and as a mechanism to narrate mystery, confusion, altered/distorted or magical

reality”

[Weedon et al. 2014, 117]. Sherwood Rise

creates tension between the static story (i.e., the printed book) and the dynamic

story (i.e., the AR story), which “was important to keep the

reader engaged across platforms”

[Weedon et al. 2014, 118]. This tension also applies to Modern Polaxis. The interplay between layers is a crucial

part of AR’s contribution to the literary experience. Consequently, we argue that AR

has the potential to enrich storyworlds. It can create possible worlds of different

ontological statuses between which tensions may arise and expand the storyworld in

time and space.

Theoretical perspectives

In AR literature, the “reality” that is augmented through an overlay of a

digital medium may be location-based, anchored in a geographical, spatial reality, or

it may be image-based, represented in a physical medium [Li et al. 2017].

With fictional narratives, the “reality” level does not exist independently of

the text. This means that in fiction, AR functions as an interplay between levels

that may be characterised as possible worlds, albeit expressed in different media.

Ryan [Ryan 2019] noted that possible world (PW) theory, transferred

from its origin in philosophy and modal logic, can shed light on the narrative

experience. For narratologists, PWs are “constructs of the

imagination, as objects of aesthetic contemplation, and as conditions of narrative

immersion”

[Ryan 2019, 62]. In line with Ryan [Ryan 2019], we

assume that immersion in a storyworld is essential to the experience of narrative

fiction.

Ryan and Bell, in their work on narrative semantics inspired by PW theory, focused on

the internal organisation of storyworlds, which they described as “entire modal universes consisting of multiple worlds”

[Ryan and Bell 2019, 18]. One world will appear to the reader as the

actual world within the text (i.e., textual actual world, TAW), whereas the others

are alternate possible worlds (TPWs) [Ryan and Bell 2019, 3]. As

Ryan [Ryan 2015, 70] stated in her PW theory, “The central element is commonly interpreted as ‘the actual world’ and

the satellites as merely possible worlds. For a world to be possible, it must be

linked to the centre by a so-called accessibility relation”. These

accessibility relations can be necessary, possible or impossible [Ryan and Bell 2019, 4]. Which world is seen as TAW is determined by

the reader’s act of “recentring” into the narrative universe, where what appears

as narrative facts comprises the TAW.

This understanding is in line with the so-called modal realism

formulated by philosopher David Lewis, who pointed out that what is actual is

indexical: “Our actual world is only one world among others. We

call it actual not because it differs in kind from all the rest but because it is

the world we inhabit” (Lewis 1979 in [Ryan and Bell 2019, 7]). A TAW may also include the characters’ private worlds, revealing their state of

mind (i.e., beliefs, dreams, desires and fears). “Through these

imaginary constructs, narrative universes acquire distinct ontological

levels,” according to Ryan and Bell [Ryan and Bell 2019, 19].

These levels are imperative for understanding how AR literature may blend worlds.

Since AR merges digital and analogue textual experiences, it can be seen as

transfictionality [Saint-Gelais 2005] or transmedia storytelling [Jenkins 2007]. Ryan [Ryan 2019, 71] discussed the

basic operations of transfictionality and sorted out three: expansion, modification

and transposition. These have inspired our discussion of how the augmented layer

contributes to the aesthetic experience of AR literature.

Ryan [Ryan 1991] also presents three dimensions of storyworlds:

completeness, distance and size; the former two are most relevant to our discussion.

In philosophical PW theory ontological completeness is a condition for PWs to count

as worlds. Fictional PWs, in contrast, are characterised by not being complete. On

the contrary, Lubomír Doležel [Doležel 1998] described fictional worlds

as areas of indeterminacy. Ruth Ronen [Ronen 1994, 12] stated that

“the fictional world system is an independent system whatever

the type of fiction constructed and the extent of drawing on our knowledge of the

actual world”. According to Ryan [Ryan 1991], completeness

does not require a total description of settings or characters; rather, it raises the

question of how much the reader needs to know to become immersed in the storyworld.

Missing information does not necessarily threaten completeness; indeed, it may

encourage the reader to supply information based on their own life experiences, as in

Wolfgang Iser’s [Iser 1978] reception theory, in which filling empty

spaces and dealing with indeterminacies are vital to the reader’s encounter with the

text. A different matter involves ontological gaps in the storyworld [Ryan 2019, 75], which may include contradictions within the TAW and

between the PWs comprising the narrative universe.

Distance concerns the storyworld’s relation to the actual world, which involves a

range of variations, from realistic to fantastic stories. The TAW of the storyworld may deviate from the world as we know it, as long as it is consistent within its own logic. The distance from the reader’s actual world can be described in terms of how

many rules in the actual world can be broken in the TAW of the storyworld [Ryan 2019, 65]. According to what Ryan [Ryan 1991]

coined the principle of minimal departure, readers imagine a fictional

world to be the closest possible to the actual world they inhabit and make only the

changes mandated by the text. A storyworld may even contain elements or events that

the reader would consider logically impossible. Here, Ryan [Ryan 2019]

distinguishes between paradoxes that contribute to the plot on the one hand and

contradiction for its own sake on the other. The former is limited to certain areas

and may “open logical holes in the fabric of storyworlds”

[Ryan 2019, 66]

As mentioned previously, the reader is central in determining which possible world to

consider actual in the storyworld. This points to the reader’s role in interpreting

how actual and possible worlds relate within the storyworld. Umberto Eco [Eco 1984, 246] includes the reader as an active part of the

constellation of possible worlds that comprise the narrative universe. He described

three types of possible worlds connected to the fabula, the characters and the

reader, respectively. The first type represents the fabula as a succession of states

mediated by events that correspond to the actual world of the narrative (i.e., the

TAW). The second type corresponds to the characters’ mental activities, involving

their imaginations, beliefs and wishes (i.e., TPWs, according to Ryan). The third

type of world is found in the unfolding of the story in the reader’s mind.

Including a reception perspective on the interplay between possible worlds in AR

fiction is hence in correspondence with PW theory and the specific situation of

reading digital narratives. The readers are central through their perceptions of what

makes up the actual world of the text and their assessment of how this relates to the

actual world of their own life experience. The readers also play an active part in

interacting with the digital layer of AR.

In his reception theory, Iser is concerned with what the text does in

the encounter with the reader. He sees the text as “a network of

response-inviting structures”

[Iser 1978, 34], in which meaning emerges through the reader’s

semantic operations. He stated that “fiction devoid of any

connection with known reality would be incomprehensible”

[Iser 1993, 1] and that “the literary text is

a mixture of reality and fiction, and as such, it brings about an interaction

between the given and the imagined”

[Iser 1993, 1].

Iser [Iser 1993] described the semantic operations specific to reading

fiction as a triad of fictionalising acts inscribed in the text and realised in the

reading event. The first is the act of selecting recognisable elements from the

actual world; the second is the act of combining them in new ways in the fictional

world; the third is the contract of reading the text as fiction, which in our view

involves an open attitude towards the PWs included in the storyworld. Iser’s

perspectives were based on written literature, but he emphasised that these semantic

processes do not primarily function on the level of words but rather meanings [Iser 1993, 20].

We find that Iser’s argument about the interplay between the fictive, the real (or

actual) and the imaginary (or possible) brought together by the reader’s interaction

with the text also has relevance for reading AR literature. In the case of AR comics,

blanks and indeterminacies may arise in the gutters between panels, or in the

interplay between words and images and other modes in the multimodal AR ensemble. In

the following, we take the case of Modern Polaxis as a

point of departure for analysing the interplay of worlds in AR fiction, be they

actual, possible or impossible, and we discuss the reader’s position and how the

augmented layer may affect the literary experience. Based on this case, we finally

discuss what the AR interface may contribute to digital literature more

generally.

Analysis

Modern Polaxis represents two different ways of seeing

the world based on two versions of the diary of one fictional character presented in

two media: a comic book with one or more panels on each page, and an AR app adding

colours, animations and soundscape, effectively expanding or modifying the story

presented in the book. The AR layer does not work unless you have the book at hand,

whereas the book stands poorly by itself without the AR layer, as it does not present

the full story. Together, these two elements create one aesthetic work and comprise

one storyworld, albeit divided. The main character is presented on the Modern Polaxis website as “a paranoid

time traveller” who “believes the world we live in is a

holographic projection from another plane in the universe.”

From the very beginning, Modern Polaxis invites the

reader to make ontological reflections by starting with a presentation of Plato’s

allegory of the cave. In this allegory, people are trapped and chained in a cave,

watching a stone wall where shadows are projected from real-world elements, passing a

fire behind them, thus resembling a shadow theatre. They believe the shadows are the

actual world, while Polaxis states that “the shadows are as close

as the prisoners get to viewing reality”

[Campbell 2014b, 1]

[1].

Through this, the question is raised of what is real and whether our experiences can

be trusted to give access to real knowledge, which, in Plato’s philosophy, is the

world of ideas. In the book version, the prisoners seem to be inside the cave,

staring at stone walls. The AR layer adds blue skies where the stone wall used to be

and the stone walls’ structures suddenly become trees, effectively enhancing the cave

allegory’s question of whether the perceived reality can be trusted. This opening

scene is positioned outside the time and space of the storyworld, serving as a

framework for understanding — and questioning — the worlds presented through

Polaxis’s diary.

This philosophical framing may be key to understanding the text’s use of AR, with the

analogue book representing the TAW and a TPW, while the digital enrichment of the AR

app represents an additional PW, including comments, doubts and suspicions. Another

philosophical reference is the principle of “time binding”

[Campbell 2014a, 4], a concept known from Polish-American scholar

Alfred Korzybski, which concerns how memories may be transferred in time and space

through the use of symbols. In Modern Polaxis, this

seems to support the main character’s efforts to escape the limitations of human

perception and knowledge of the world. Korzybski was best known for his dictum,

“the map is not the territory”, which indicates that

human knowledge is limited and that no one can have direct access to reality. This

fundamental doubt about what one perceives through the senses is set as a premise for

the story to be told. It affects the reader’s trust in what is being told and, at the

same time, substantiates the protagonist’s reasoning for challenging these

limitations within the fictional world.

These tensions are also connected to the book’s and the app’s subjective first-person

viewpoint. The story is told through the paranoid and delusional Polaxis without

other commenting viewpoints than the philosophical framing mentioned above. The

diary’s verbal text appears to be handwritten by Polaxis and is not easily

accessible, as it is very small and dense. This makes the text physically hard to

read. The images in the book are mostly line drawings in black and red, and image and

verbiage are tightly interwoven. Even though the book looks small, this is a

comprehensive work. The amount of written verbal language is significant and central

to conveying the story. The digital layer enriches the text with an elaborate

soundscape, colours and animation, sometimes omitting or replacing the book’s verbal

text. These layers present the complicated worlds that Polaxis is struggling to

navigate, which we explore further in the next section.

The worlds of Modern Polaxis

Modern Polaxis’s book and AR app constitute one

storyworld. According to Ryan [Ryan 2019, 64], “[n]arratives that represent travel between different worlds in the

planetary or insular sense” present only one storyworld. For analytical

clarity, we first discuss what constitutes the TAW and how it relates to other

possible worlds (TPWs) in the book before turning to the app and what it contributes

to the storyworld’s totality. Next, we explore more closely how the storyworld

unfolds in time and space. Then, we discuss how ontological gaps in this particular

constellation of PWs, enabled by the digital layer, challenge how the TPWs and the

TAW are understood.

To determine what to consider the TAW of the storyworld, we looked for accessibility

relations that connect to the reader’s actual world, relations that make up the grid

of a TAW easily recognised by a reader. Several points in time and place connect this

storyworld to the reader’s actual world, including geographical names (e.g.,

Brisbane, the Amazon and St. Viateur Bagels) and specific dates (see Table 1). If

seen in connection to the fabula as a succession of states mediated by events [Eco 1984], the TAW is, in a simplified version, the story of a young man

from Brisbane with the mundane job of scanning military maps. After a traumatising

crisis that makes him feel trapped [Campbell 2014a, 3–9] and a

night “fuelled with spiced rum”

[Campbell 2014a, 17], he starts a new life. He randomly travels to

Montreal, Canada, where he meets new friends (i.e., Maki, Feliz and Hoze, and later,

Eddie, Avel, Carlos and Javier) who help direct him to travel to Peru and explore

drugs and shamanism. Finally, we see him five years later as a patient taking

schizophrenia medications in a Tasmanian mental hospital.

The main TPW in the book medium is represented by the protagonist’s thoughts and

feelings expressed by verbal text and images. The multimodal comic presents the

verbal text as coming directly from Polaxis’s mind, whereas the images place the

reader in a position to observe Polaxis from the outside. Nevertheless, as readers

are led to believe that the diary is both written and drawn by Polaxis, the images

somehow still represent his perspective. The drawings in the book are, to some

extent, realistic (although often both symbolic and exaggerated), contributing to the

TAW of Modern Polaxis standing out as a complete world,

where the subjective world of Polaxis is embedded in what Ryan characterizes as an

“entire universe” that contains “not only an actual world of narrative facts, but a multitude of possible worlds

created by the mental activity of the characters”

[Ryan 2019, 65].

As Modern Polaxis is presented as Polaxis’s diary, the

TAW and the TPW are closely intertwined; the TPW of Polaxis’s memories, beliefs and

ideas appear as the narrative’s driving force. Hence, the accessibility relations

between TAW and TPW are necessary for understanding Polaxis’s actions and reactions.

In other cases, the connections are possible, since the allusions to drug abuse and

disillusions are possible explanations of how he sees the world. Other explanations,

such as time splitting [Campbell 2014a, 5], transmigration [Campbell 2014a, 8] or living in a fifth-dimensional hologram [Campbell 2014a, 17], represent accessibility relations that seem

impossible or radically increase the distance from the reader’s actual world.

The AR app presents another possible world that complicates the storyworld of Modern Polaxis: the so-called hidden journal of

Polaxis. On one hand, the hidden journal in the AR layer may be seen as a description

of a parallel world named “Intafrag,” but on the other hand, it may be seen as a

mental possible world created by the main character’s delusions and paranoia. This

question remains open throughout the entire story, although the last image, in which

central characters are placed in a mental institution, might suggest the latter. The

reader may see this plot’s driving forces as the adventurous desires of youth gone

wrong and/or as developing a psychiatric diagnosis. However, because of this

uncertainty, the TPW represented by the AR layer may ultimately challenge what may

represent the TAW, thus raising doubts about the ontological statuses of all worlds

of Modern Polaxis — in line with the philosophical

framing of the cave allegory.

The worlds of Modern Polaxis unfolding in time and space

In this section, we look closely at how Modern Polaxis’s storyworld unfolds in

time and space and how differences in these dimensions create tensions between the

worlds. Table 1 summarises the stated times in the work and the places that

Polaxis visits at these points in time. A turning point in the story is marked

with the heading “RIP Polaxis of the past for this statue is

dedicated to the Polaxis of the future”

[Campbell 2014a, 18]. This marks the beginning of Polaxis’s

travels and a new way of perceiving time and space, and the book’s verbal text

states that “a new reality begins”.

Only some events are accurately dated, and there are significant gaps in the

story. The dates do not seem to differ much between the book and app, except for

once, when the in-flight magazine says 2 July [Campbell 2014a, 26], and the journal entry [Campbell 2014a, AR 26] states 29

June. This would not be strange if the time difference were the other way around,

with the date on the magazine being before the date Polaxis wrote about the

flight. The fact that time seems to turn backwards represents a gap that might

refer to time travel.

| Time | Page | Place in book | Place in app |

| No date specification | 1 | In a cave | Outside |

| 9 December 2008 | 3 | Dark alley + future apartment — on a ship | Same as the book |

| One night (retrospect) | 12 | Dark alley | Intafrag junction/space |

| Two years earlier | 13 | A small office on the seventh floor of the Zenith building in Spring Hill, Brisbane | Same as the book |

| One weekend | 14 | IT expo at Brisbane Convention Centre | Same as the book |

| After a night out | 17 | From a bench to the McDonald’s carpark | Same as the book |

| “RIP Polaxis of the past.” “A new reality begins:” Modern Polaxis of the future | 18 | ||

| 7 February 2009 | 19 | Montreal, Canada | Same as the book |

| 11:47 pm | 20 | St. Viateur Bagels | Same as the book |

| 20 minutes later | 24 | At a home party (in an apartment) | Same as the book |

| 29 June 2009 (In app: in-flight magazine says 2 July) | 26–27 | Montreal >> Lima, On airplane, later bus. Bus stops somewhere in the Andes |

Bus stop — ancient world of Intafrag? |

| 2 July 2009 | 28 | Lima >> Cusco, Peru | Same as the book |

| 3 July 2009 | 29 | Pisac, Peru | Intafrag Peru/Tibet |

| 35 | The Yellow Rose of Texas Café, Iquitos suburbia | Iquitos (Peru’s gateway to the Amazon) | |

| 7 February 2009 | 46 | Montreal, Canada | Same as the book |

| 2014 In app: a new time phase | 48 | Terrylands, mental hospital, Burnie, Tasmania | Same as the book |

Table 1.

Overview of times and places in Modern

PolaxisThe first part [Campbell 2014a, 3–17] tells the story of

Polaxis’s past in retrospect and gradually reveals his background up to the point

when the story is being told. This is where his connection to Intafrag and the

fear of its agents is first established in the AR layer [Campbell 2014a, AR 5–6]. The story about the Polaxis of the

future, the Modern Polaxis, is told in the present

tense and moves chronologically forward in time from the party in Montreal in

February 2009 to Polaxis’s experiences in Peru and the Amazon in June/July 2009

(except for the logical gap between the flight and magazine dates). Then there is

a flashback to February 2009, followed by a five-year leap at the end to the

mental hospital.

In Table 1, we see how changes in time and place move quickly forward from page to

page in some phases, while there are mainly two phases where time seems to come to

a halt: one in Polaxis’s past and one in his future. This may be seen as

ontological gaps in time that constitute indeterminacies in the fabula. The first

appears as a dream triggered by the introduction of the concept of “time binding”

[Campbell 2014a, 4]. Here, Polaxis recollects a sensation of

burning in the book TPW and being chased by Intafrag agents through dark alleys in

the app. In the book layer he refers to the experience as “transcendence. Time splits in two”

[Campbell 2014a, 5], “the breakdown of cells

into light”

[Campbell 2014a, 7], “transmigration”

and “Mind + Body transfer”

[Campbell 2014a, 8]. As the process accelerates, the AR layer

adds no words [Campbell 2014a, AR 7–10] but instead intensifies

the experience with swirling movements and scary sounds. These memories from the

past explain what happens to the “Polaxis of the

future”

[Campbell 2014a, 19]. These incidents may represent

corresponding ontological gaps in the two TPWs.

Another example of ontological gaps in the TPWs is a corresponding experience of

a time in the future when Polaxis travels from Montreal to Lima. The spaces of the

airplane and bus seem to overlap [Campbell 2014a, 26–27] and

immediately follow the confusing experience of time going backwards (from 2 July

to 29 June). Hence, neither time nor space is perceived as stable: “My position...Is not stable…”

[Campbell 2014a, 27]. In the AR layer, this experience is

presented as a “time fold” (a portal between two

overlapping realities) [Campbell 2014a, AR 30]. The following

events include Polaxis’s experience in Peru, which has been given a double

explanation. He is invited to try Ayahuasca, “a psychoactive

homebrew traditionally prepared by Amazonians for the purpose of healing the

body of toxins and interfacing with the divine”

[Campbell 2014a, 31], and he joins the ceremony led by the

shaman Javier in the Pisac sacred valley [Campbell 2014a, 37–45]. On page 46 in the book, the lost journal entry connects back to 7 February in

Montreal, and the AR layer connects these two timeless phases with the word “purge”.

These experiences of time coming to a halt represent ontological gaps or

indeterminacies in the storyworld across book and app. The main difference

concerning the time perception between the analogue and digital layers is that the

time gaps in the book seem like “normal” gaps in time. The reader will not

perceive the changes in time and place as missing information, but as events that

have occurred but are not told. In the digital layer, however, these gaps are

explained as actual time travel, occasionally jumping between places. When, in the

end, Polaxis is in the mental hospital, he refers to an incident in Montreal five

years earlier: “The blow to my head knocked me unconscious. I

was out long enough for the plant creatures to time-bind me to this

reality”

[Campbell 2014a, AR 48]. It is as if those five years never

actually transpired. Hence, there is a conflict between accessibility relations

and the timeline of the book and the app, respectively. The alternate timeline of

the AR layer represents a transposition that may challenge the storyworld’s

logical consistency, according to Ryan [Ryan 2019, 72].

The places where Polaxis visits seem to vary more between the analogue and digital

layers than the time references. As Løvlie [Løvlie 2009, 19]

explained, “the concept of ‘place’ should not only

be treated as a physical location in space, but also as a psychological, social

and cultural phenomenon (…) ‘places’ are spaces that are

valued”. This is relevant to the relations between narrative spaces in

the worlds of Modern Polaxis. It seems that the places in

the two different layers carry different values, even though the physical

locations of both are mostly the same. The colours, sounds and animations of the

AR layer reinforce the notion of being in a different place, as do the people

inhabiting the two different layers when changing their personalities from the

analogue to the digital medium. These changes are ontological gaps, creating

uncertainty between the two layers.

As mentioned in the Theory section, relations to storyworlds can be verified in

the actual world; they can be possible or impossible. In Modern Polaxis, references to placenames that can be verified in the

actual world are overrepresented in the book version. Many of the actions,

especially in the book version, are possible, for example, the travels, alcohol

and drug abuse and the parties. However, the connection to Intafrag and the

Intafrag agents is impossible if delusions are not taken into account. The main

level of possible references and real-life references is represented by the book,

whereas the impossible is represented largely by the app. Moreover, the illegal

actions concerning the actual world, such as drug abuse, are not “hidden” in

the journal, which perhaps indicates it is not the police or other authorities

that the journal is hidden from; rather, the main character in his paranoia hides

it from the representatives of Intafrag.

The question of the distance between the world of the readers and Polaxis’s world

is not straightforward. It depends on which world is taken as a point of

departure. The idea of the parallel world of Intafrag contributes to the

distancing of the entire storyworld from the actual world of the reader. Even so,

there is a question of whether the experiences of the TPW in the AR layer, the

Intafrag experiences, should be seen as real experiences or as delusions caused by

drug abuse. The notion of drug experiences has a much shorter distance from the

real world than a parallel universe, even considering that some readers may

believe in parallel worlds. Ryan [Ryan 2019, 66] states that

“ghost stories could be credible for people who believe in

the occult.” However, such beliefs are not mainstream, and because of

that, if Intafrag is seen as a result of paranoia and delusions, the distance from

the real world is much shorter.

The distance between the PWs of the AR layer and the book can be illustrated by

looking for verbal references that occur only in the app, and that may even seem

impossible in the TAW. Words that appear only in the app are “Intafrag” (15 times) and “creatures” (23

times). The word “key,” referring to entering Intafrag,

is only mentioned in the app. Furthermore, “agent(s)”

appears frequently in the app version but is only mentioned three times in the

book. These words connect directly to the world of Intafrag and are not compatible

with what would be considered the ontological rules of the TAW. Polaxis’s diary,

where he expresses his experiences and thoughts in the book layer, is hence closer

to the TAW than the AR layer, which is said to be his secret diary.

Visually, certain symbols or objects of symbolic value also serve to establish

relationships between the TPWs. For example, a triangle first appears on page four

and in the AR layer is emphasised by blinking colours. Later, it reappears on a

pendant [Campbell 2014a, 9], which is later described as an

anchor point [Campbell 2014a, AR 33]. These objects play an

essential role in time binding, which is reminiscent of Korzybski’s theory of how

memories may be transferred by using symbols, perhaps indicating a connection

between movement in time and space and inner perception (memories).

Polaxis is haunted by the ambivalence of having friends but distrusting them, as

he is insecure about whether they are, in fact, friends or disguised Intafrag

agents. In the book, many characters seem to be fellow travellers whom Polaxis

incidentally meets. However, the AR layer reveals their relations to Intafrag. For

instance, on the last page, in the image from the mental hospital, the characters

Maki and Hoze appear to be sitting next to Polaxis on a bench. In the AR layer,

however, their faces are crossed out while the verbal text states, “This is not Maki or Hoze. They’re Intafrag agents sent here to

monitor me”

[Campbell 2014a, AR 48]. On the same page, Dr. Affeldt is

labelled a “neuropsychiatrist” in both the book and AR

layers, while earlier, his name and profession were only revealed in the AR layer.

Then he was presented as the founder of time-binding theory who tried to find a

“synthesis of the first chemical agent to disrupt

Intafrag”

[Campbell 2014a, AR 6]. Hence, Polaxis’s early suspicions of

being a test subject in the AR layer are explained in the book layer by Dr.

Affeldt, asking him to take his schizophrenia medication [Campbell 2014a, 48].

At the house party in Montreal, a drug dealer named Feliz appears, and the verbal

text in the book describes him as a “dapper-looking

fellow”

[Campbell 2014a, 22], whereas in the AR layer, he is revealed as

a gatekeeper holding “several ancient keys to enter

Intafrag”

[Campbell 2014a, AR 22]. Eddie, who is a character that Polaxis

meets on his way to Peru, has connections to Intafrag in the app layer, but he is

oblivious to his Intafrag experiences, which only Polaxis can see [Campbell 2014a, AR 32]. In the AR layer, normal people attending

a shaman ceremony in Peru become strange green creatures from Intafrag and so on.

Hence, the people who inhabit the worlds of Modern Polaxis

are not easily trusted. These people, even if radically changing their roles in

the story, also connect the TPW of the AR layer with the worlds of the book layer.

Nevertheless, there are always some relations that remain the same, reminding the

reader that the layers are part of the same story.

According to Ryan [Ryan 2019, 76], some fictions create worlds

with ontological gaps. Ontological completeness presupposes that “for every contradictory pair of propositions, one must be true

and another false in that world”

[Ryan 2019, 74]. In Modern

Polaxis, the references to Intafrag may, for the reader, represent an

ontological gap in the storyworld; however, from the viewpoint of the main

character, Intafrag is the only truth maintained throughout this story.

Consequently, Polaxis’s ontological doubts are about how people and events in his

actual world are related to (or infiltrated by) Intafrag. Perhaps the possible

worlds of the book and the AR layers are ontologically different, but they are

still two sides of the same storyworld, according to the main character. Still,

there is a question of how this affects the TAW. In the case of a parallel

universe, it would connect to the TAW on a more profound level than in the case of

being a purely mental possible world. The story’s philosophical framing poses the

radical question of what is real. If the parallel universe of Intafrag is given

priority, this radically changes the understanding of the TAW, altering

propositions from true to false.

To explore how different worlds may be perceived by the reader, the next section

presents a reader-oriented perspective on the simultaneous experiences of the

partly conflicting possible worlds depicted in Modern

Polaxis.

Reading Modern Polaxis

The literary experience of an AR work differs from reading a traditional book and

other kinds of digital literature by simultaneously offering two different sides of

the story. Physically, when reading Modern Polaxis, it

is possible to read the book first and then use the app to read a different version

of the story. We expect readers to read the book and app in parallel, first reading a

page in the book and then seeing what the app reveals. Seeing the story change while

reading is one thrill of the AR app. It is also crucial to understand the work as a

whole. This is one storyworld unfolding in two different layers transpiring

simultaneously. The starting point is that the aesthetic work comes to life through

the act of reading [Iser 1978], which is experienced through the senses

and ultimately activates the reader’s imagination.

Fiction, imagination and sensory experience

Fictional narratives invite interpretive work that caters to the imagination. As

Ryan [Ryan 2019, 70] claims, “when a text

creates a storyworld, we imagine that there is more to this world than

what the text represents.” As mentioned in the Theory section,

reading fiction includes a triad of fictionalising acts [Iser 1993]:

the fictive, the real and the imaginary brought together by the readers’

interaction with the text. Certain elements in Modern

Polaxis expand the possibilities for imagination; for instance, the

people whom Polaxis meets are genuinely mysterious, and how he reaches some places

in his travels is unclear. This applies to both analogue and digital layers. One

might assume that adding information automatically narrows the possibilities for

the reader’s imagination. However, Intafrag creates a new space for imaginative

deduction and spatial immersion. In this way, Modern

Polaxis opens itself up for the reader to create a more complex

storyworld based on their imagination, thus providing space for the reader’s

uncertainties and ambivalences in line with Polaxis’s experience of being in the

world.

Regarding the question of how the interplay between worlds in AR literature may

affect the reader’s literary experience, we explore this through Iser’s [Iser 1984] concept of aesthetic response. Iser connects aesthetics

with perception and sees the aesthetic effect as a form of

realisation stemming from the human senses. This view on aesthetics reflects the

etymological meaning of the Greek word, aísthēsis – sensation. When reading AR literature, the physical

sensory experience is simultaneously perceived in both analogue and digital

layers, which creates the potential for a multitude of connections between what

the senses perceive and how this translates to an act of immersion and inner

experience.

The two TWPs may be seen in light of the platonic question raised at the beginning

of the story. Which world is apprehended as the most real world, the one closest

to the TAW, as they are both materialised in the physically touchable book or the

alternate, mental one? The world in the book layer is generally less colourful

than in the digital layer. The digital layer adds perceivable differences, such as

colour, movement, sound and sometimes picture-like elements. The visual

impressions in the app layer are perceived as more salient than the book’s visual

expressions due to the colourfulness and movement. Adding the digital layer

changes the visual style, in this case giving more emphasis to affect [Painter et al. 2013, 32] and hence providing potentials for the

readers’ emotional immersion. The liveliness of the AR layer might indicate that

this is the most “real” part of the story. To complicate this, however, the

analogue layer is touchable and concrete, whereas the digital layer is volatile

and intangible.

As an example of this layered reading experience, we will have a closer look at

the episode in which Polaxis travels from Montreal to Lima, following the

ontological gap where time seems to move backwards, as described in the previous

section. Pages 27-28 are part of this travel, describing Polaxis on the bus in

Peru [Campbell 2014a, 27] and what he sees as the bus stops [Campbell 2014a, 28].

On page 27, Polaxis is depicted on a bus, stating it could be anywhere. He falls

asleep and wakes up “somewhere else”, which turns out

to be Peru. Throughout the comic book the background is white and cross ruled,

alluding to Polaxis’s diary being jotted down in a notebook. The image is rather

detailed, but a line drawing. On this page the verbiage is in white on black

background. There are drawings depicting a chaotic mess, including elements

resembling tentacles and branches, over and under the outline of Polaxis on the

bus. The page can be read as a comics page divided in three panels horizontally,

in which the upper and lower panel represent a chaos foreshadowing the monster on

the next page.

As the AR layer is projected upon the book page, colours appear in the bus window

displaying a photographic image of mountains in motion, to indicate that the bus

is driving. When looking closely, green, huge, monster-like creatures with long

thin insect-like legs emerge in the mountain landscape. The predominantly green

monsters connote the green Martians of past times science fiction, perhaps

pointing to the outer worldly of a parallel universe. The sound of a vehicle (the

bus) merges with strange sounds, perhaps guttural sounds from the monsters, and

sounds of large rocks falling. The sounds create feelings of great unease and may

be perceived as scary. This is however an interpretation; it is the reader’s

starting point in the principle of minimal departure [Ryan 1991]

that makes the reader perceive the engine-like noises and the moving image as the

bus moving. The photographic image in the AR layer brings the representation

closer to the real world of the reader, hence questioning the ontology of the TAW

of the book. The green monsters, however, appear hand drawn, perhaps leading the

reader to think that they are a product of Polaxis’s imagination. Projecting the

AR layer, the colour of the letters shifts from white to red, making them pop out,

which in turn gives them a greater semantic load. Polaxis in the AR layer says he

closed his eyes on the plane and ended up on the bus, that his position is not

stable and that he sees “strange shapes” in the

distance, presumably referring to the monster-like creatures only visible in this

layer. It is up to the reader to draw connections between the book and the AR-

layer. The indeterminacy lies in which layer to believe in. Are the monsters

products of Polaxis’s imagination, as they are not present in the original “hand-written” book? What is the origin of the soundscape?

These are fundamental tasks of interpretation for the readers to solve through

their imagination. What is specific for comics reading is the interpretative work of closure that happens when the reader draws connections between panels. Adding the AR layer expands this reading space by adding a new kind of “gutter” between book and app.

On the opposite page, the text states Cusco, Peru, July 2nd 2009. Words and image

in the book describe a rather mundane situation of the bus stopping in the Andes,

and construction workers building new roads and installing a traffic light system,

which Polaxis finds strange, as the place is quite rural and he states that there

is no traffic. A red, thin handwriting on the left reads: “Every [man][2] wants to see” and this sentence

seems to be continued on the right with “the ancient

world!”

When the AR layer is projected, a large monster appears, resembling the monsters

on the previous page. The animated monster is multi-coloured, but mainly green,

and it is not possible to identify its face or body parts. It seems to have

tentacles rather than humanlike limbs. The men in the picture who are raising

traffic lights in the book version now seem to try to control the monster. The

sounds resemble roars, presumably from the monster, along with distant human

voices. It is not possible to make out what the voices say, and again it is the

principle of minimal departure that makes the reader understand these sounds as

human voices from the workers. The red letters stating “every

man wants to see” now say “Intafrag”. They

turn turquoise with a red background and are surrounded by lots of spinning

arrows, as if symbolising confusion or a compass that is not working. This is an

example of the explicit Intafrag references in the AR layer. The verbal text on

the top of the page reveals that Polaxis does indeed feel confused, wondering

whether what he sees is hallucinations, or whether he actually sees Intafrag.

There is an evident void between the perceiving of a mundane, but odd situation in

a street, and the revealed monster of the AR-layer. How the layers are connected,

is a question of interpretation, where the perspective taken by the main character

is only one of many options. The soundscapes and visual layers of AR create

unease, merging the sounds of humans and engines with undefinable roars; and the

colours, movements and landscapes of the actual world with the hand drawings of

the monster. The AR layer questions the ontology of the textual worlds of Modern Polaxis because these elements bring the static

situation in the notebook to life.

The experience of reading this AR comic represents new ways of viewing the

relations between the real and the virtual [Farman 2017]. Touching

the book while using the app maintains the physical sense of the book medium,

while at the same time sensing the AR layer being projected over your hands. The

app is transitory, it is only seen and heard when swiping over a page; as opposed

to the physically stable book, which can be moved from one place to another

without pictures and verbal text disappearing. The touchable book is held against

the stronger visual (i.e., colours, movement, etc.) and audible experiences of the

app. These sensory experiences underline and thematise the question of what is

real or what we may know about the world rather than providing an answer.

The game of interpretation

Gaps for the reader to fill in the text occur when text segments are indirectly

connected and can break the expected order in the text [Iser 1984, 302]. Indeterminacies require the reader to make individual decisions on

textual meanings. Even if there are several connections between the analogue and

digital layers, there are also gaps between them. The main gap consists of the

lack of explanation regarding the layers’ differences, raising the question of

what is real. An interesting aspect of the gaps in time is that, according to

traditional storytelling, they are perceived in the book as gaps for the reader to

fill, whereas the digital layer insists on explaining the gaps with time

travelling. This repeats the question of what is delusional and what is real. In

this uncertainty, the reader participates in the main character’s delusions and

his struggle to be in two worlds simultaneously. This distance and tension between

the two layers may cause the reader to feel a sense of insecurity.

The tension between the layers is a driving force in the story. The reader’s

curiosity is driven by revealing the differences between the layers, rather than

by being immersed in the actual story, which is not very causally driven. This is

a form of indeterminacy that seems related to the interpretative work of closure

in comics reading. There is little explanation for why the events occur and the

information on characters other than Polaxis is very limited. Polaxis himself has

a past that is only vaguely elaborated, for instance, with an ex-girlfriend who

appears only in a flash. The mundane, the usual and everyday aspects of life, are

not emphasised in the work, nor is the causality between events. Mystery surrounds

Polaxis, and the reader gets a first-hand impression of his insecurity,

estrangement, existential anxiety and uneasiness. The work renders the impression of having access to someone’s delusional and paranoid mind as if the readers are getting to see something that is not for them to see.

The line of events may not be as interesting as the way the app makes the reader

feel. This feeling of estrangement and uneasiness constitutes a common ground for

the analogue and digital TPWs. Polaxis does not seem to feel comfortable in any of

these worlds. This may be seen in connection to the modern in the

Modern Polaxis story. The modernist feeling is

that of estrangement, existential anxiety and uneasiness. The threats in the app

come from the Intafrag agents, but Polaxis does not seem to find the real world

very appealing either. He wishes to travel through time and space, which is what

he simultaneously fears. In a way, he is lost in both worlds.

Polaxis is presented as a human in a human world and thereby ontologically like

the reader, which is a prerequisite for immersion [Ryan 2019, 74]. However, the potential discrepancy between Polaxis’s and the reader’s views of

Intafrag makes Modern Polaxis a work that does not

effortlessly provide immersion. This is because Polaxis is not necessarily a

character with whom the reader identifies. However, the emotional state of

uncertainty and vulnerability, mainly emphasised in the AR layer, may invite

identification and emotional immersion. Even if the feeling of estrangement is a

general human experience of the modern, it might be said to connect to the story’s

psychological dimension. Anxiety and unease are also commonly associated with

psychological conditions that sometimes need professional treatment. According to

this view, the TPWs constitute both opposites and mutual preconditions for

interpretation.

The narrative possibilities for tensions between the worlds in the case of Modern Polaxis counteract the human pull towards

everything adding up in the end. The AR layer questions whether the Intafrag

notions are only manifestations of the protagonist’s delusions or whether they

are, in fact, real. The latter acts against the conclusion implied in the end when

Polaxis is in a mental hospital. The aesthetic experience of the work, namely

frustration and feelings of alienation and unease, lies in this counteraction.

Since the narrative is difficult to follow, it requires the reader’s

concentration. Ryan [Ryan 2015, 68] defined concentration as a

type of “attention devoted to difficult, non-immersive

works”. It is possible, however, to have an experience of the app

without understanding the full story. Perhaps the aesthetic experience of unease

is even stronger than the actual narration of events.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss more generally how AR can contribute to literary

experiences. AR can enhance experiences with sound, colours and animations, but what

can AR contribute beyond pop-up-like environments with sound effects [Helms 2017]. Does this technology have the potential to enrich literary

experiences in more profound ways? First, we will look at AR contributions in terms

of Ryan’s [Ryan 2019] transfictional operations: extension,

modification and transposition. Then, we discuss some differences between

location-based and object-based AR and, lastly, the potentials concerning the degree

of interactivity in AR works.

Extension is a transfictional operation that “adds new stories to the fictional world while respecting the facts

established in the original”

[Ryan 2019, 71]. These additional story elements may be more or

less true to and more or less consistent with the TAW. AR also has the potential to

expand storytelling experiences by blending fictional worlds with the reader’s actual

world. In AR stories, such as those of Wonderscope,

users may see the room they are in or even their hands merging into the story. This

draws the reader closer to the narrative and invites empathy for the characters. In

other cases, ambivalence may result from the interplay between the layers, or the

layers may be polarised by providing alternative viewpoints and perspectives [Weedon et al. 2014], as we see in the Modern

Polaxis story. Whether the aim is to deepen the feeling of closeness and

empathy or to open new, surprising narrative spaces, AR contributes to the

storyworld’s extension and elaboration.

In contrast to extension, modification more radically changes the

original narrative’s plot [Ryan 2019, 71]. These changes may

concern the characters’ behaviours and missions, as in the case of Modern Polaxis, or modify how events play out and ultimately

change the ending that feeds back in one’s interpretation of the entire story. In

sum, the layers may offer alternative plotlines or more or less elaborate courses of

events. Transposition entails a plot moving into a different temporal or

spatial setting [Ryan 2019, 71]. Here, AR may offer new

possibilities across the narrative dimensions of time and space. Time leaps may occur

in narratives across media, such as books, films and theatre, but the possibility of

operating in different times and places in the simultaneous display of analogue and

digital layers may be specific to AR technology. More generally, AR may inspire a

broad range of interplay between parallel or contrasting timeframes; for example, an

AR story with historical events in one layer and something resembling the present day

in the other (or present-day versus the future, or any other combination).

The complexity of space being simultaneously perceived in two different layers is

AR-specific. The AR layer may extend and elaborate the textual worlds in terms of new

information and additional modes of expression, such as colour, movement and sound.

The layers may also display more separate possible worlds than in Modern Polaxis, thus inviting the creation of stories in

parallel or contrasting worlds. Such choices may invite a great variety of options

for spatial immersion. Spatial transpositions seem vital to AR technology.

The interplay between the AR layer and a physical object or a geographical, spatial

reality is unique to the AR experience [Li et al. 2017]. The merging of a

digital layer with the physical reality in which the reader’s body is located, is

perceived differently through AR work than in other media. This adds to the relevance

of PW theory, as the complexity of textual possible worlds plays out in different

layers simultaneously. The AR layer can express both closeness and distance to the

TAW; in the case of Modern Polaxis, AR contributes to

distancing the reader from the TAW. This interplay between different dimensions or

worlds has significant potential for expanding the storyworld. The potential

complexity of the interplay between worlds seems extensive through the combination of

the physical and AR layers. However, one could also imagine a less complex

relationship between the analogue and the digital. The PW of the AR layer may support

or subvert the premises of other textual worlds.

As previously mentioned, AR has the potential to play with both surroundings and

artefacts. In this respect, there is a difference between space-oriented and

object-oriented works. In location-based works, the opportunity arises to exploit the

fact that the user must move physically from one place to another, which influences

their experience of the story. In object-based AR, one can envision endless

possibilities in the choice of objects onto which the story is projected, moving far

beyond the traditional comic book medium employed in Modern

Polaxis. One example is the Merge Cube,

formed like a giant dice that fits in your hand, onto which the multilinear AR story

57° North is projected; however, the potential is not

utilised in this app, where turning the cube has much the same function as turning a

book page. The potential for further development appears to be extensive, with

stories yet to be told.

While interactivity in Modern Polaxis is kept to a

minimum, the possibilities for interactions in terms of tasks for the reader to solve

or paths to choose in AR work seem endless. Using interactivity in narrative apps

carries potentials to expand aesthetic experiences in several ways [Hagen 2020]. The already complex combination of AR and the actual and

possible worlds of the story may be additionally augmented through the creative use

of interactivity.

Topics about location-based AR and interactivity could be extended to future research

on AR narratives. For this paper, we have merely touched upon some of the

possibilities that lie in an approach based in narratology and possible world theory.

Further research on AR and aesthetic experiences, could broaden this perspective with

insights from multimodal theory or game studies, which would expand the understanding

of how AR literature works.

Conclusion

The analysis of Modern Polaxis shows how AR can contribute to aesthetic experiences through the parallel structure — the simultaneous sensation of the story’s different layers that cannot be experienced in a format other than AR. The potential complexities of reading AR comics may be understood as an extension of the two dimensions characteristic of comics discussed by Scott McCloud [McCloud 1993]: The juxtaposition of panels, as well as that of words and images. McCloud categorises six kinds of transitions between panels, of which action-to-action is the dominant in comics within western culture. Interestingly, he finds cultural differences, where aspect-to-aspect transitions are more common in comics from Eastern culture (Japan). This kind of transition “bypasses time for the most sake and set a wandering eye on different aspects of a place, idea or mood” [McCloud 1993, 72].

As we have pointed out in the analysis, the interpretative work of closure that is involved in connecting what happens in a sequence of panels across gutters, is multiplied in reading AR comics. Adding the AR layer may work as a new kind of “gutter.” In the case of Modern Polaxis, this contributes primarily to the mood by elaborating different aspects of the storyworld.

Furthermore, in AR comics the digital layer caters for including new modes such as

sound and animation to the words and images in printed comics. These are experienced

simultaneously, and may expand, modify, transpose, or even contradict the printed

story. The simultaneous merging of layers carries a specific potential for

elaborating the emotional immersion in the story, rather than the sequence of actions

unfolding in time. Hence the AR layer may be particularly interesting as it

complements sequential art with nuances, paradoxes and embodied experience through a

fuller multimodal orchestration.

The prerequisite for such potential expansions in time and space to be successful in

augmenting the story told, rather than disturbing the narrative drive or displacing

attention from meaning to form, is that the AR layer is consistently integrated in

the story, as Helms points out [Helms 2017, 62]. In the case of

Modern Polaxis, the AR layer affects every spread

throughout the story, and this playing with worlds is thematically justified by

framing the story with Plato’s allegory of the cave. It may be no coincidence that we

find such a thorough AR strategy in a unique, stand-alone story, written, illustrated

and animated by one artist, in close cooperation with programmer and musical

composer.

As implied in our discussion, these insights from reading Modern

Polaxis may transfer to other kinds of AR literature through an

understanding of panels, gutters and layers as spaces of interpretation. In Wolfgang

Iser’s more general theory of aesthetic response, this experience of connecting

events over time and space, can be seen as gaps, blanks and indeterminacies, which

invite the reader into the work of interpretation by connecting syntagmatic

combination with paradigmatic selection. This opens possibilities for telling

multifaceted, complex stories, and this complexity is sensed through AR technology

and at least partly driven and caused by it. In simultaneously displayed layers lie

possibilities for unique aesthetic experiences. Hence, AR may contribute to complex

storyworlds by presenting possible worlds in different layers and exploiting the

spatial complexity of textual worlds specific to AR. The reader’s literary

experiences may be correspondingly complex, as the narrative worlds expand and reach

beyond the reader’s previous literary experiences.

On a more general note, we could say that the relations between levels of reality in

AR fiction remind us of the challenges of interpretation. Iser [Iser 2000, 147] claims that any interpretation opens a liminal

space, and he connects a poetic quality [Iser 2000, 150] to this

“space between”

[Iser 1996]. He sees interpretation as a dynamic process where this

space invites the reader to perform new meaning. We find that this awareness of the

game of interpretation is amplified by the layered structure of AR narratives. The

core of the AR function lies in the different aesthetic perceptions of the layers, as

well as in the differences and tensions of the layers, the gaps between them, and

despite all of this, their creation of a common ground for interpretation.

Notes

[1]

Modern Polaxis is written in capital letters only. For

readability, we cite from the work using both capital and small letters. Although

the book is not paginated, we have provided page numbers for the content. We use

“AR” in front of page numbers when the reference is to the app.

[2] The [man] is not written but drawn as a simple symbolic

presentation of “man”.

Works Cited

Azuma et al. 2001 Azuma, R., Baillot, Y.,

Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S. and MacIntyre, B. “Recent

advances in augmented reality,”

IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 21(6) (2001):

34-47. https://doi.org/10.1109/38.963459

BlippAR 2011 BlippAR.

BlippAR Group Limited, 2011. https://www.blippar.com/

Campbell 2014a Campbell, S. Modern Polaxis [book and smartphone application software], (2014).

Campbell 2014b Campbell, S. Modern Polaxis [website]. 2014. https://modernpolaxis.com/

ChanLin 2018 ChanLin, L. “Bridging Children’s Reading with an Augmented Reality Story

Library”, Libri, 68(3) (2018): 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2018-0017

Devineni et al. Devineni, R., et al. Priya. https://www.priyashakti.com/

Doležel 1998 Doležel, L. Heterocosmica: fiction and possible worlds. Johns Hopkins University

Press, Baltimore (1998).

Eco 1984 Eco, U. The Role of the

Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Bloomington, Indiana UP

(1984).

Farman 2017 Farman, J. “When

Geolocation Meets Visualization.” In S. Morey and J. Tinnell (eds), Augmented Reality; Innovative Perspectives Across Art, Industry, and

Academia. Parlor Press, Anderson, South Carolina (2017): 177-199.

Green et al. 2019 Green, M., McNair, L., Pierce, C.

and Harvey, C. “An Investigation of Augmented Reality Picture

Books: Meaningful Experiences or Missed Opportunities?”

Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 28(4)

(2019): 357–380.

Hagen 2020 Hagen, A. “The Potential

for Aesthetic Experience in a Literary App,”

Nordic Journal of ChildLit Aesthetics, 11 (2020): 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2000-7493-2020-01-02

Helms 2017 Helms, J. “Potential

Panels; Towards a Theory of Augmented Comics.” In S. Morey and J. Tinnell

(eds), Augmented Reality; Innovative Perspectives Across Art,

Industry, and Academia. Parlor Press, Anderson, South Carolina (2017):

47-62.

Iser 1978 Iser, W. The Act of

Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Johns Hopkins, London

(1978).

Iser 1984 Iser, W. Der Akt des

Lesens: Theorie ästhetischer Wirkung. W. Fink, München (1984).

Iser 1993 Iser, W. The fictive and

the imaginary: charting literary anthropology. John Hopkins University

Press, Baltimore (1993).

Iser 1996 Iser, W. “Coda to the

Discussion.” In S. Budick and W. Iser (eds), The

Translatability of Cultures: Figurations of the Space Between. Stanford

University Press, Stanford, CA. (1996): 294–302.

Iser 2000 Iser, W. The Range of

Interpretation. Columbia University Press, New York (2000).

Jenkins 2007 Jenkins, H. “Transmedia Storytelling 101,”

Confessions of an Aca-Fan (2007). http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2007/03/transmedia_storytelling_101.html

Li et al. 2017 Li, J., van der Spek, E., Feijs, L.,

Wang, F. and Hu, J. “Augmented Reality Games for Learning: A

Literature Review.” In N. Streitz and P. Markopoulos (eds), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, volume 10291, Springer

International Publishing (2017): 612–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58697-7_46

Liestøl 2011 Liestøl, G. “Situated Simulations Between Virtual Reality and Mobile Augmented Reality:

Designing a Narrative Space.” In B. Furht (ed.), Handbook of Augmented Reality, Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0064-6_14

Liestøl 2019 Liestøl, G. “Augmented Reality Storytelling: Narrative Design and Reconstruction of a

Historical Event in situ,” International Journal of

Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM), 13(12) (2019): 196–206.

https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v13i12.11560

Løvlie 2009 Løvlie, A.S. “Poetic

Augmented Reality: Place-bound Literature in Locative Media.”

MindTrek '09: Proceedings of the 13th International MindTrek

Conference: Everyday Life in the Ubiquitous Era, September 2009: 19–28.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1621841.1621847.

McCloud 1993 McCloud, S. Understanding comics. Harper Perennial, New York (1993).

Mighty Coconut 2017 Mighty Coconut. 57° North. Mighty Coconut (2017). https://www.mightycoconut.com/57north

Painter et al. 2013 Painter, C., Martin, J.R. and

Unsworth, L. “Reading Visual Narratives.”

Image Analysis of Children’s Picture Books. Equinox,

Sheffield (2013).

Prakash et al. 2020 Prakash, S., Fini, S., and

Kazemifar, N. Priya's Mask. Rattapallax, 2020.

Ronen 1994 Ronen, R. Possible

worlds in literary theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

(1994).

Ryan 1991 Ryan, M.-L. Possible

Worlds, Artificial Intelligence and Narrative Theory. Indiana University

Press, Bloomington (1991).

Ryan 2015 Ryan, M.-L. Narrative as

Virtual Reality 2: Revisiting Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and

Electronic Media. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (2015).

Ryan 2019 Ryan, M.-L. “From Possible

Worlds to Storyworlds: On the Worldness of Narrative Representation.” In A.

Bell and M-L. Ryan (eds), Possible Worlds Theory and

Contemporary Narratology. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln

(2019).

Ryan and Bell 2019 Ryan, M.-L. and Bell, A.

“Introduction: Possible Worlds Theory Revisited.” In

Alice Bell and Marie-Laure Ryan (eds), Possible Worlds Theory

and Contemporary Narratology. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln

(2019).

Saint-Gelais 2005 Saint-Gelais, R. “Transfictionality.” In D. Herman, M. Jahn and M.-L. Ryan

(eds), The Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory.

Routledge, London (2005): 309–10.

Shields 2020 Shields, R. Neon

Wasteland. (2020) https://www.neonwastelandgame.com/

Weedon et al. 2014 Weedon, A., Miller, D., Franco,

C. P., Moorhead, D. and Pearce, S. “Crossing Media Boundaries:

Adaptations and New Media Forms of the Book,”

Convergence, 20(1) (2014): 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856513515968

Wonderscope 2019

Wonderscope. Within Unlimited Inc., vers. 1.18, 2019.

Apple App Store, https://apps.apple.com/us/app/wonderscope/.

Wu et al. 2013 Wu, H-K., Lee, S. W-Y. Chang, H-Y. and

Liang, J-C. “Current Status, Opportunities and Challenges of

Augmented Reality in Education,”

Computers & Education, 62 (2013): 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.024

Yilmaz et al. 2017 Yilmaz, R. M., Kucuk, S. and

Goktas, Y. “Are Augmented Reality Picture Books Magic or Real for

Preschool Children Aged Five to Six?”

British Journal of Educational Technology 48(3) (2017):

824-841. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12452