Abstract

This article sheds light on the methods and meaning of W. E. B. Du Bois’ 1899 study

of the everyday lives of Black residents of Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. It does so

by juxtaposing the way Du Bois conducted his research with our contemporary efforts

to recover, recreate, and preserve The Philadelphia

Negro using digital and geospatial technologies to document historical and

contemporary patterns relating to race and class. Beginning with an exploration of

primary source documents that provide new details about how Du Bois went about his

original research, we focus on the humanities and social science research methods

that he employed. Of note is the color-coded parcel-level map Du Bois created to

illustrate Black social class status, which reflected both the influence of the

Social Survey Movement and Du Bois’ efforts to present a new understanding of the

color line. His findings were groundbreaking, considering that most white scientists

of his time assumed Black people to be biologically inferior and socially homogeneous.

Instead, he documented the variability and social stratification within

Philadelphia’s Black population and the systematic exclusion they faced because of

anti-Black racism. Our ongoing project — The WARD: Race and Class

in Du Bois’ Seventh Ward, which seeks to recreate Du Bois’ study —

includes new technologies and participatory research methods that engage high school

and college students. In-depth, intergenerational oral histories conducted with

students also add a new dimension to this work and complement our high school

curriculum, which incorporates online mapping, documentaries, a board game, a walking

tour, and a mural to engage others to create their own primary sources. This research

provides a historical context for today’s racial tensions as we seek new ways to

address the 21st century color line.

INTRODUCTION

Responding to a telegram invitation from the University of Pennsylvania, an ambitious

28-year old Harvard-trained scholar brought his new bride to Philadelphia in 1896 to

answer questions posed by the white women of the College Settlement Association: Why are

the Black residents of Philadelphia not doing better economically and what is the

solution to this “Negro Problem”? [

Philadelphia Press 1896]. He

was able to set aside the patronizing nature of the prompt — he was sure that the women

already had their answer to that question; the indignity of being named an “assistant”

in the sociology department rather than an instructor; the fact that he would not have

an office; and the overall lack of official recognition — and accepted the invitation

[

Lewis 1993]. This ambitious and talented scholar, none other than W. E. B. Du Bois,

methodically collected and analyzed data through surveys, interviews, and observations

along with a review of archival sources, census data, local government reports, and the

press, ultimately reframing the idea of the “Negro problem.”

Rather than focusing on Black residents as a problem, he transformed the phrase to mean

the distinct problems of a group of people who faced systematic racial discrimination in

the primary domains of their lives, including health, occupation and employment,

education and literacy, housing and the environment, voting, and institutional life.

That is racism, not Black pathology, explained the poverty and crime the women of the

College Settlement Association lamented. In making this argument, Du Bois set himself

apart from most other scholars and Americans at the turn of the 20th century. Today,

that argument is central to Critical Race Theory (CRT) and the #BlackLivesMatter

movement, and nearly half of all Americans acknowledge that Black people face “a lot” of

discrimination [

Daniller 2021] [

Ray and Gibbons 2021].

This article examines Du Bois' 1899 study of the everyday lives of Black residents of

Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward by juxtaposing his research methods with our contemporary

efforts to recover, recreate, and preserve

The Philadelphia Negro: A

Social Study (hereafter,

The Philadelphia Negro) using

digital and geospatial technologies. Here, we explore the primary source documents,

mining them for new details of how Du Bois conducted his research, and focus on the

humanities and social science research methods he employed. In particular, this article

focuses on Du Bois' survey techniques and the color-coded parcel-level map that he

created of Black social class status, reflecting the influence of the Social Survey

movement and his efforts to present a new understanding of the color line [

Du Bois 1903]. The range of methods he used to analyze a wide array of primary and secondary

data was essential to his groundbreaking findings. Disavowing the view of most social

scientists of his time that Black people were (a) biologically inferior and (b) socially

homogeneous, Du Bois documented both the variability and social stratification within

Philadelphia’s Black population. With this careful empirical investigation, he pointed

to the need to recognize the full humanity of Black people and address what today we

call anti-Black racism in order to solve this “Negro Problem” [

Du Bois 1899, 386].

This study continues Du Bois' work by using what Gallon, writing within the field of

Black digital humanities, calls the “technology of recovery, characterized by efforts to

bring forth the full humanity of marginalized peoples through the use of digital

platforms and tools” [

Gallon 2016, 44].

More than one hundred years after the publication of Du Bois' seminal work, society is

still plagued with the same problems of individual prejudice and structural racism,

which have been reinvented, reshaped, and reinforced. Our ongoing project,

The WARD: Race and Class in Du Bois' Seventh Ward, employs both

old and new technologies to recreate Du Bois' study and advance research on the state

of America’s race problem. A property-level historical geographic information system

(GIS) of Du Bois' Seventh Ward forms the foundation of our contemporary research and

our teaching and public history project based on

The Philadelphia

Negro. Like Du Bois, we use interviews and observation, archival research,

census data, local government reports, directories, the press, and mapping. We depart

from Du Bois' study, however, by using new technologies and participatory research

methods that engage high school and college students as part of the research process

[

Ammon 2018]. While Du Bois wrote primarily for an audience of elite white leaders, our

project seeks to make the lives of Seventh Ward residents accessible to young people

across race, class, and gender. The in-depth, intergenerational oral histories conducted

with students add a new dimension to this research; these histories also complement our

high school curriculum’s interactive mapping, documentaries, board game, walking tour,

and mural. These curriculum tools allow students to become co-researchers. Much like Du

Bois’ later research during his time at Atlanta University, our process engages students

to help to create visualizations [

Mansky 2018].

Our project extends Du Bois' original work through the use of both old new

technologies, amplifying his central argument that white people of that era were unwilling to

embrace the full humanity of their Black neighbors. White people typically viewed Black people

as an inferior race at the time of his study, understood in today’s language as white

supremacy and anti-Black racism. This manifested in material subordination, structural

forms of exclusion, and individual prejudice, all techniques used by white people to keep most

Black people from the significant economic advancement that they had anticipated when they

migrated to the North [

Loughran 2015]. We revisit Du Bois' work by focusing on the

stories and experiences of the Black residents he studied, as well as subsequent

generations of Black residents who have lived in and around the Seventh Ward. We also

directly engage youth of color and their white peers in the recreation, examination, and

expansion of Du Bois' seminal work. In so doing, we highlight ways to examine the

contemporary challenges of the color line — gentrification, housing discrimination,

racial profiling, and mass incarceration — that we and our young people face. This

research also provides historical context for today’s racial unrest and persistent

racial inequities.

The Influence of the Social Survey Movement and Social Work

Too often, scholars understand Du Bois' approach to studying the Black population of

Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward exclusively within academic sociology rather than seeing

connections to applied sociology, social work, philanthropy, and the Social Survey

Movement. Concentrated in England and the United States between 1880 and 1920, the

Social Survey Movement produced numerous empirical studies concerning the realities of

urban life for immigrants and the poor [

Bulmer et al. 1992] [

Lewis 1993]. Charles Booth,

the wealthy British merchant, launched the movement with a scientific investigation in

the 1880s to assess the level and nature of poverty in London. Booth employed an army of

women to make house calls and register children for school; he then cross-checked the

data they collected with information from philanthropists, social workers, policemen,

and other sources [

Englander and O’Day 1995]. Booth’s great multi-volume work,

Life and Labor of the People of London [

Booth 1899], detailed the social

classes, patterns of income, employment, and forms of labor in several thousand pages of

text. A series of block-level color-coded maps, depicting the spatial nature of poverty

in 19th century London, provided a compelling summary of the overwhelming data which

proved critical for Booth’s call to move from debate to action [

Kimball 2006].

The female sociologists and social workers of that time were exemplary practitioners of

applied sociology and welcomed Du Bois into their circle [

Deegan 1988]. Hull-House

Settlement founder Jane Addams and social reformer Florence Kelly produced the

Hull-House Maps and Papers in 1895. Like Booth’s efforts, they

used community-based research involving extensive field work and interviews to produce a

series of color-coded maps of nationalities and wages of residents by household [

Deegan 2013]. This work also included empirical studies of immigrants, working conditions,

specific laborers, labor unions, social settlements, and the function of art in the

community, in addition to a critique of social services. Influenced by their scholarship

and activism, Du Bois joined forces with these pioneers, who were largely marginalized

by the male-dominated academy. They shared the dual goals of documenting social

conditions and using their research to fight the inequality of Jim Crow segregationist

and discriminatory policies and practices [

Deegan 1988, 309]. Booth and the women of

Hull House served as models for Du Bois’ work in Philadelphia in their methods and

commitment to documenting poor social conditions to inspire social change [

O’Connor 2009] [

Zuberi 2004] [

Du Bois 1899].

Du Bois' Invitation to Philadelphia

On June 8, 1896, University of Pennsylvania Provost Charles Harrison sent a telegram to

W. E. B. Du Bois, who was then teaching classics at Wilberforce College in Ohio, the

first private Black college in the country. Harrison’s telegram invited Du Bois to

conduct a study of Black people living in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. The invitation — like

many of today’s text messages — was terse, simply stating: “Are ready to appoint you for

one year at nine hundred dollars maximum payable monthly from the date of service. If

you wish appointment will write definitely” [

Aptheker 1997]. Though formally issued by

the University, Du Bois' invitation came at the prompting of the women who ran

Philadelphia’s College Settlement Association (CSA). Philanthropist Susan P. Wharton, a

member of the wealthy Wharton family for whom the the University of Pennsylvania’s

business school is named, convened a meeting at her home of leading citizens interested

in the welfare of Black people in Philadelphia. She said that the study should focus on the

“problems” of the Black residents and the “obstacles to be encountered by the colored

people in their endeavor to be self-supporting” [

Lindsay 1899, vii–xv]. Wharton’s

motivation, consistent with the goals of the Social Survey Movement, blended

philanthropy, science, and political advocacy [

Lindsay 1899] [

Katz and Sugrue 1998]. In

addition to Penn’s Provost, her neighbor Dr. Harrison, Wharton invited merchant and

philanthropist Robert C. Ogden, editor Talcott Williams, and Fannie Jackson Coppin, the

prominent African-American educator and first lady of the Mother Bethel African

Methodist Episcopal Church. She initially imagined hiring a white woman social worker to

conduct the research but was swayed by Samuel Lindsay, a faculty member in Penn’s

Sociology Department, who recommended Du Bois. Du Bois' proven work ethic, his

education at Fisk and Harvard universities, and his history and sociology studies in

Germany made him the ideal candidate for this research [

Katz and Sugrue 1998]. Du Bois

was grateful to have a new job; he considered this opportunity and his recent marriage

to have “spelled salvation” from the small-mindedness of the Midwestern Evangelical

college where he had suffered for two years [

Du Bois 1968].

Data Collection and Analysis for The Philadelphia Negro

As a young scholar, Du Bois had abundant faith in the power of science to effect social

change. “The Negro problem was in my mind a matter of systematic investigation and

intelligent understanding,” he explained in reference to the invitation to conduct

research in Philadelphia [

Du Bois 1968, 136]. “The world was thinking wrong about race,

because it did not know. The cure for it was knowledge based on scientific

investigation” [

Du Bois 1968, xxvi]. His research incorporated multiple methods of

inquiry and analysis. The door-to-door surveys he conducted with all the Black

households in the Seventh Ward were the most time-consuming aspect of his study. He sat

in the parlors, kitchens, and living rooms of 2,500 households listening and documenting

their stories. W. E. B Du Bois — unlike Booth, Kelly, and Addams — had no research

assistants; he conducted all the interviews himself, following a detailed interview

schedule he developed. In addition to this list of questions for heads of household, he

developed questions about Black businesses and streets or alleys (see Figure 1). In what

was perhaps the University of Pennsylvania’s only direct involvement with the study, the

institution sent these questionnaires out for comment to leading scholars, including

Booker T. Washington, but there is no evidence that Du Bois made any significant changes

based on this outside feedback. He explained in

The Philadelphia

Negro that he usually spoke with the head of the household’s wife for between 10

and 60 minutes, with an average duration of 15 to 25 minutes [

Du Bois 1899, 63]. All

together, he likely spent more than 800 hours conducting these interviews, five months

of full-time work by today’s standards. However, Du Bois likely worked longer days and

weekends given the tight schedule and limited compensation — approximately $30,000 in

today’s dollars, slightly more than a doctoral stipend at the University of Pennsylvania

today and significantly less than a typical post-doctoral salary.

In addition to the exhaustive door-to-door surveying, Du Bois consulted notable local

Black figures, whom he acknowledged in his preface to

The Philadelphia

Negro [

Du Bois 1899, iv]. Reverend Henry Phillips was the leader of Church of

the Crucifixion, a Black Episcopal church located at 8th and Bainbridge Streets on the

southern edge of the Seventh Ward. Du Bois described the Church of the Crucifixion as

“perhaps the most effective church organization in the city for benevolent and rescue

work” [

Du Bois 1899, 217].

This assessment downplayed the role of Mother Bethel A.M.E., the most historic of the

Black churches in the area. “This church [the Church of the Crucifixion] especially

reaches after a class of neglected poor whom the other colored churches shun or forget…” [

Du Bois 1899, 217]. George Mitchell, another of Du Bois' advisers, was among the few

Black lawyers admitted to the Philadelphia bar before 1900

[

Smith 2006, 184]. W. Carl Bolivar, a journalist and bibliophile, wrote a column for

The Philadelphia Tribune, the leading Black newspaper.

Eighty-year-old Robert F. Adger, a well-off furniture dealer who owned a store on South

Street, was the sole businessman whom Du Bois listed as an advisor. Adger founded the

Benjamin Banneker Institute, an intellectual and literary association [

Dorman 2009].

William Dorsey, a Black archivist who kept scrapbooks detailing issues and events

relevant to Black people in Philadelphia well into the twentieth century, rounded out the

group [

Lane 1991].

In addition to collecting information from these primary sources, Du Bois “went through

the Philadelphia libraries for data [and] gained access in many instances to private

libraries of colored folk” [

Du Bois 1968, 124]. The five-page bibliography in

The Philadelphia Negro listed the secondary sources that Du Bois

consulted, including state legislation, history books, and church reports. He cited the

works of 35 Black Philadelphian authors including Richard Allen, Martin Robinson

Delaney, Jarena Lee, William Still, and Benjamin T. Tanner [

Du Bois 1899]. Throughout

the book, there are references to the administrative data he reviewed, particularly

vital statistics and disease records from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health,

crime records from the Philadelphia Police Department, and newspaper clippings. Du Bois

relied on church histories, minutes from local church conferences, and a report of

churches from the eleventh U.S. census in 1890 [

Carroll & U.S. Census Bureau 1894] to capture the organized life of Black people through their congregations. Using such

records as the membership growth and value of property owned by the African Methodist

Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Du Bois presented the state of the Church, a task

facilitated by having both the headquarters and publishing house of the A.M.E. Church

located in Philadelphia.

The greatest data analysis challenge Du Bois faced was making sense of the answers from

his door-to-door survey. Du Bois had to keep track of each household’s address and then

connect that address to a map of the properties in the Seventh Ward to produce the

color-coded property map of social class. There is no record of how he recorded the data

in the field, particularly whether he adapted the large sheets that census enumerators

used or came up with his own system. However, in the spring of 1897, presumably after

finishing the surveys, Du Bois ordered 15,000 cards corresponding to the schedules from

a Philadelphia printer. He probably transferred his field notes onto these cards so he

could sort them to generate his summary statistics (see Figures 2 and 3). His original map

appears to be based on the 1895 or 1896 Bromley fire insurance map — either an actual

copy or a tracing. We also know that in 1890, the most recent census before Du Bois

created his maps for Philadelphia, the U.S. Census categorized people as Indian, Chinese

or Japenese, Black, Mulatto (“3/8-5/8 black blood”), Quadroon (“1/4 black blood,”),

Octoroon (“1/8 or any trace of black blood”), or white [

Brown 2020]. Du Bois does not

specify whether he included bi-racial or multi-racial people as Black, using the single

category of “Negro” for all the households he interviewed, perhaps anticipating the

collapsing of these Black and multi-racial identities into a single category and

underscoring that any Black ancestors meant for practical purposes that one was

“Negro.”

Before Du Bois could match his household data to the corresponding properties, he had to

determine social class based on his survey results. He did not include a direct question

about social class on any of his schedules; instead, he used questions about income and

employment — both the type of work and consistency of it — as the most salient factors

for making this determination. By making house visits, he was also able to consider “the

apparent circumstances of the family judging from the appearance of the home and

inmates, the rent paid, the presence of lodgers, etc.” [

Du Bois 1899, 169]

. Du Bois deliberately used similar categories as Booth — vicious and

criminal, poor, working people, and middle class — so he could compare the distribution

of social class status among Seventh Ward residents to those of London.

Reframing the “Negro Problem”

To complete

The Philadelphia Negro, Du Bois “labored morning,

noon and night” [

Du Bois 1968, 125]. He imagined that his sponsors had already

identified the “corrupt, semi-criminal vote of the Negro Seventh Ward” [

Du Bois 1968, 194] as the problem

that prevented them from bringing about moral reform and better governance for the city.

Black people sold their votes to Republicans in exchange for a limited number of municipal

jobs and the protection for their voting clubs, which were often illegal drinking houses

[

Katz and Sugrue 1998]. “Everyone agreed that here lay the cancer,” he explained —

everyone except him [

Du Bois 1899, 60].

Du Bois and his wife of three months, Nina Gomer, lived in a one-room apartment at

Seventh and Lombard Street over a cafeteria run by the Settlement House, which also had

buildings on St. Mary’s Street (now Rodman Street, one block north of South Street) at

the eastern edge of the Seventh Ward. This was the heart of the “Negro slums,” home to

“loafers, gamblers, prostitutes, and thieves” — some of the people Du Bois would

characterize as “vicious and criminal” [

Du Bois 1899, 60]. He explained, “We lived there

a year, in the midst of an atmosphere of dirt, drunkenness, poverty, and crime. Murder

sat on our doorsteps, police were our government, and philanthropy dropped in with

periodic advice” [

Du Bois 1968, 122].

Still, he wrote with uncharacteristic joy about his first Christmas with Nina, who was

delighted to have a 15-cent Christmas tree “with tinsel, fruit, and cotton snow” and

five dollars to spend on him at Wannamaker’s department store [

Du Bois 1968, 129].

He wanted to use the best social science tools, transcending disciplinary boundaries and

investigating the complexity of the “Negro problem.” Though white Philadelphians largely

thought of Black people as a monolithic group marked by chattel slavery and marginalized

politically and economically, Du Bois revealed Black citizens in a new light by

introducing the notion of Black heterogeneity across class, space, religion, and

politics [

Du Bois 1899] [

Hunter 2015]. “Nothing more exasperates the better class of

Negroes,” such as himself, “than this tendency to ignore utterly their existence” [

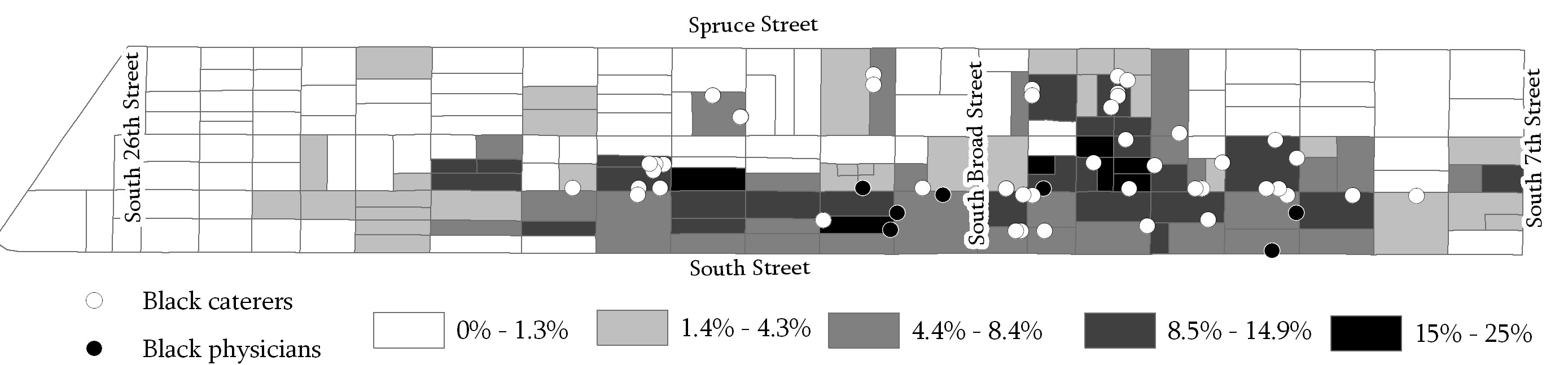

Du Bois 1899, 310]. With his color-coded parcel map highlighting the social class

differences among Black residents (see Figure 4), he advanced our understanding of these

within-group differences. He also argued indirectly that Black people were just like white people,

thus challenging the prevailing theories of the day about white supremacy.

Du Bois studied Black people in their urban enclaves, highlighting the role of the social and

physical environment in shaping their outcomes and documenting spatial inequalities,

thereby anticipating the direction that public health research would take a century

later [

Jones-Eversley & Dean 2018] [

Hunter 2013a]. He also highlighted the historical,

structural, and cultural factors that distinguished the experience of Black people from that

of their immigrant neighbors. Ultimately, Du Bois rejected biological explanations and

racial logics of Black inferiority. He rested his hopes first on the Black middle class

to save the masses from the moral disorder that contributed to their poverty and second

on the white “benevolent despot” to sweep away racial discrimination and remedy the lack

of educational and employment opportunities [

Du Bois 1899, 127].

Du Bois finished his research in Philadelphia by the end of December 1897, just as his

appointment ended and his new teaching position at Atlanta University began. He signed

off on the book’s preface 18 months later, in June 1899, while teaching and writing his

landmark essay, “The Study of the Negro Problems,” for the

Annals of

the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Inspired largely by his

work in Philadelphia, this essay served as a research agenda and call to action for the

next phase of his professional life. While on the faculty of Atlanta University, Du Bois

refined his empirical data collection and data visualization techniques to draw

attention to the significance of the color line and the plight of Black Americans at the

1900 Paris Exposition [

Du Bois 1900] [

Battle-Baptiste and Rusert 2018].

Re-Making The Philadelphia Negro WITH The WARD

The WARD: Race and Class in Du Bois' Seventh Ward is an ongoing

research, teaching, and public history project that uses geographic information systems

(GIS), individual-level 1900 U.S. census data, and archival data to recreate Du Bois'

survey research to the extent possible (see:

http://www.dubois-theward.org). Using old

and new technologies, we expand the analytical capabilities and the stories of the color

line from the 19th century to the 21st century with interactive mapping, a board game,

documentaries, an oral history collection, a walking tour, a mural, and curriculum

materials for high school students.

The WARD project materials

focus on Du Bois' life and work in Philadelphia as a diligent social science researcher

and courageous agent for social change. The project was initially funded in 2005 with a

small grant from the University of Pennsylvania’s Research Foundation; the real dollar

value of this grant was not much less than the compensation offered by the same

university to Du Bois for his original study. Our project was largely advanced with

funding from the National Endowment for Humanities and has been sustained by subsequent

small grants from local foundations, the University of Pennsylvania, and Haverford

College.

Primary Data Sources for The WARD

The WARD relied primarily on address-level 1900 U.S. manuscript

census data to recreate Du Bois’ door-to-door survey. Other primary sources included

hospital admissions records, infectious disease records, newspaper articles, crime

reports and mug books, historical photographs, court transcripts, and fire insurance

records and maps. To complement these resources, we conducted oral histories with older

members of the churches referenced in Du Bois' original study. As we revisited and

recovered Du Bois' research, we did not follow his convention of anonymizing people,

instead choosing to use the names and stories of individuals and their families as they

highlighted the daily lives and struggles of Black people in the community, believing

this would allow youth to connect more closely to them.

Maps and Spatial Data

[1]. The individual and

household-level data that Du Bois collected on Black households no longer exists, as far

as archivists and Du Bois scholars know. The individual-level data collected through the

1900 U.S. census is the best available proxy for the people Du Bois found living in the

Seventh Ward in 1897. Using the census enumerator sheets on microfilm (also available as

scanned documents on Ancestry®), student research assistants entered the census data for

the 28,000 Seventh Ward residents of all races into an electronic spreadsheet, including

their name, age, place of birth for themselves and their parents, occupation (for

adults), the number of children born and still alive (for adult women), schooling (for

children), and their relationship to the head of household. Research assistants also

created a corresponding GIS parcel layer by digitally tracing the boundaries of the

approximately 5,000 properties in the Seventh Ward based on Bromley fire insurance maps,

which also noted property ownership and the names of institutions. By lining up a

high-resolution scan of the color-coded property map Du Bois created of the Seventh Ward

with this digitized parcel layer, we were able to integrate the social grade Du Bois

assigned each property into the Seventh Ward GIS. Ultimately this “thick mapping”

collects, aggregates, and visualizes layers of place-specific data [

Ammon 2018, 13],

adding nuance and greater detail regarding race, national origin and class to

traditional archival sources.

The GIS data files work well for Lab exercises in undergraduate and graduate GIS

courses, and we made them accessible to a broader range of students through a series of

online interactive mapping platforms. Guided by worksheets, students analzyed the

historical data in these applications as well as demographic changes over time using US

Census data and Social Explorer®, a publicly-available mapping system. Students were

able to look up individual residents of the Seventh Ward based on their name, age,

occupation, and address. They could also create parcel-level maps to see patterns in

race/ethnicity, nationality, household size, children enrolled in school, homeownership,

and occupation. Because the dataset includes multiple variables, one can map multiple

parameters simultaneously to visualize associations between, for example, place of birth

and presence of boarders or servants — the best available proxies for low- and

high-income households, respectively. Census block-level aggregations of the

individual-level census data allow additional insights as distinct spatial patterns

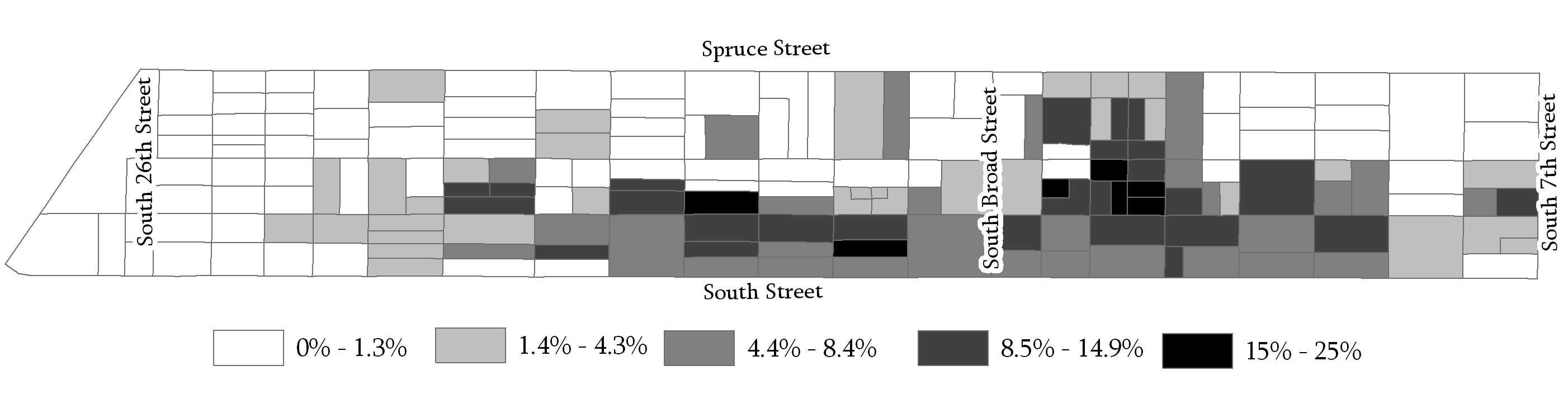

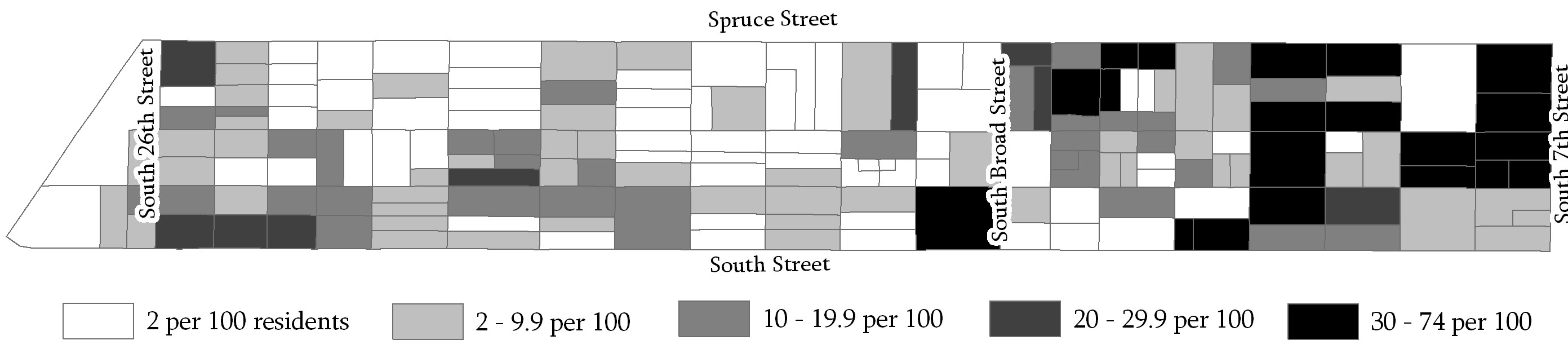

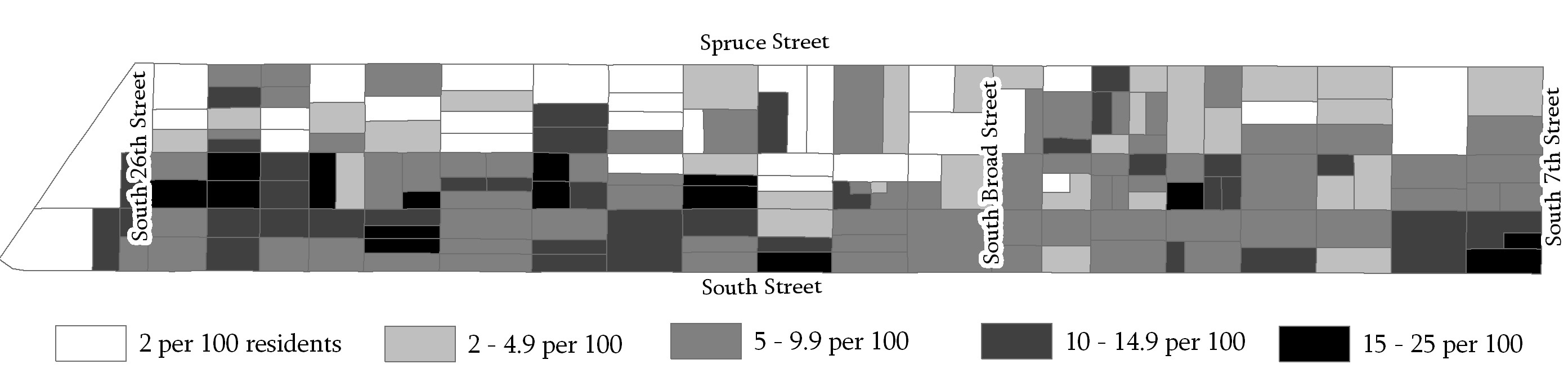

become more prominent (see Figure 6-10). The concentration of Black people in the lower half of

the Seventh Ward, lodgers/boarders on the eastern side, and live-in servants in the

northwestern section, further show this relationship between race and income. By

combining the individual geocoded addresses with block-level data, it is possible to see

that even the most prominent Black residents — physicians and caterers — lived on

predominantly Black blocks where they would have lived with Black people of diverse social

class (see Figures 5-9).

In addition to facilitating the analysis of these broad spatial patterns, the Seventh

Ward GIS makes it possible to identify some of the Black individuals and households that

contrasted with the general pattern. These include specific examples of interracial

marriage, such as 46-year-old Oscar Stewart, a Black waiter born in Alabama who was

married for 23 years to Katie, a 45-year-old housekeeper from Ireland. Many of the white

women who were married to Black men were born in other countries, but not all of them.

Similarly, while Black people rarely had live-in servants, there were some notable exceptions.

Abraham Corney, a 50-year-old Black man born in Delaware, worked as a stevedore and

lived with his wife, Virginia-born Bessie, a dress-maker; his 11-year-old son; a

63-year-old live-in servant, Lidia Anderson; and five lodgers. Arthur McKenzie, a

47-year-old junk dealer, born in the British West Indies, had a live-in servant and two

lodgers. The female servant was 23 years old and McKenzie’s daughter was 19; both

lodgers were men, one 25 and the other 26 years old.

A dozen physicians, including Nathan Mossell who founded Frederick Douglass Hospital for

Black people in 1897, and nearly 50 Black caterers, including 8 women, composed much of the

Black middle class and professional elite. Mapping this individual-level data from the

1900 Census along with block-level data on racial composition shows how even these Black

elite lived with other Black residents rather than along the wealthy white streets like

Spruce Street.

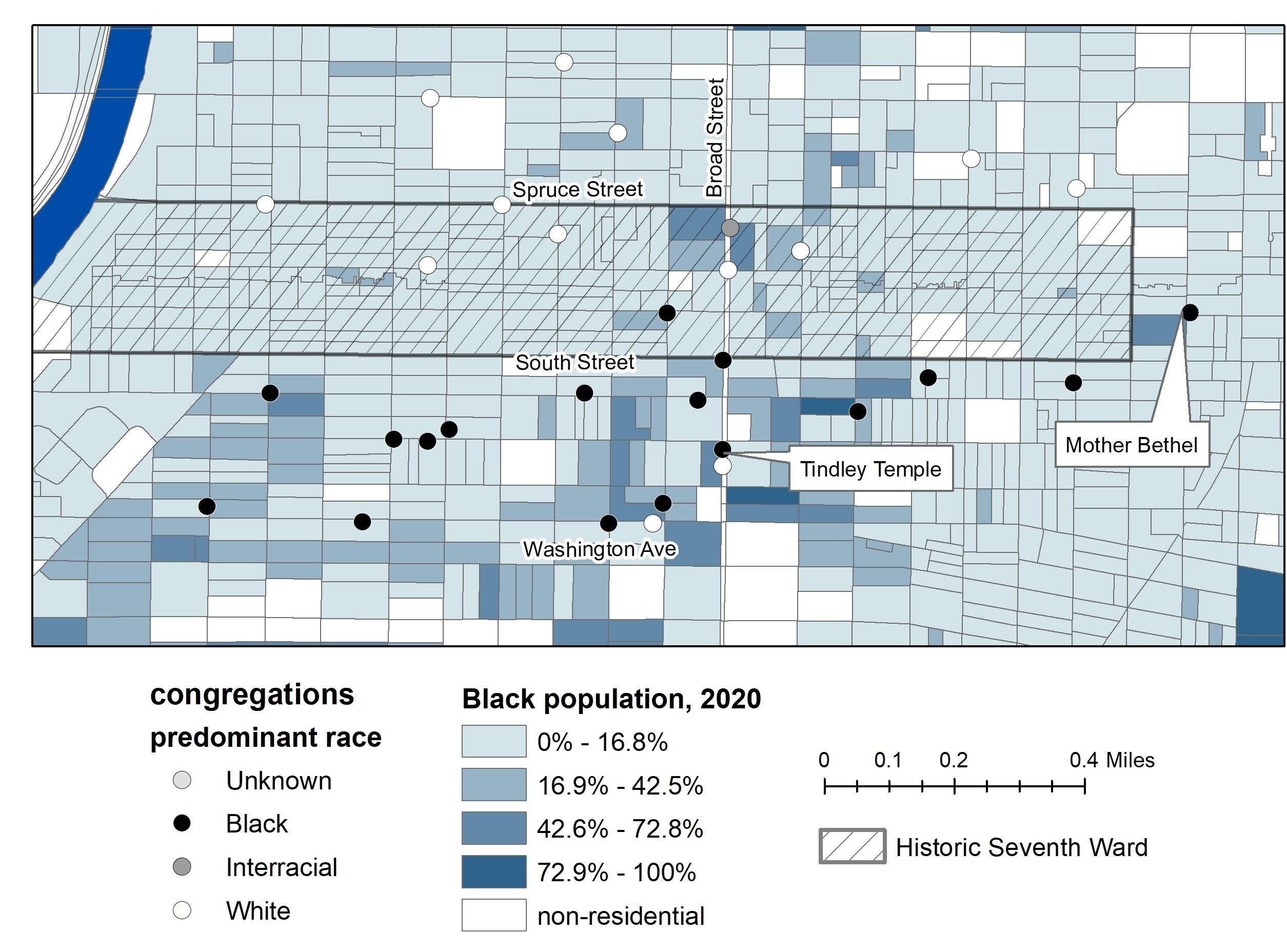

Oral histories. In 2012, we began collecting the oral histories of older African

American members affiliated with the Black churches studied by Du Bois, namely Mother

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and Tindley Temple United Methodist, earlier

known as Bainbridge Methodist Episcopal Church.

[2] These two congregations were located at the edge

of the Seventh Ward and have experienced significant racial and economic change over the

past 120 years (see Figure 10). We retrieved 30 oral histories recognizing the residents

who once lived, worked or worshipped in or near the Seventh Ward as keepers of

unrecorded history [

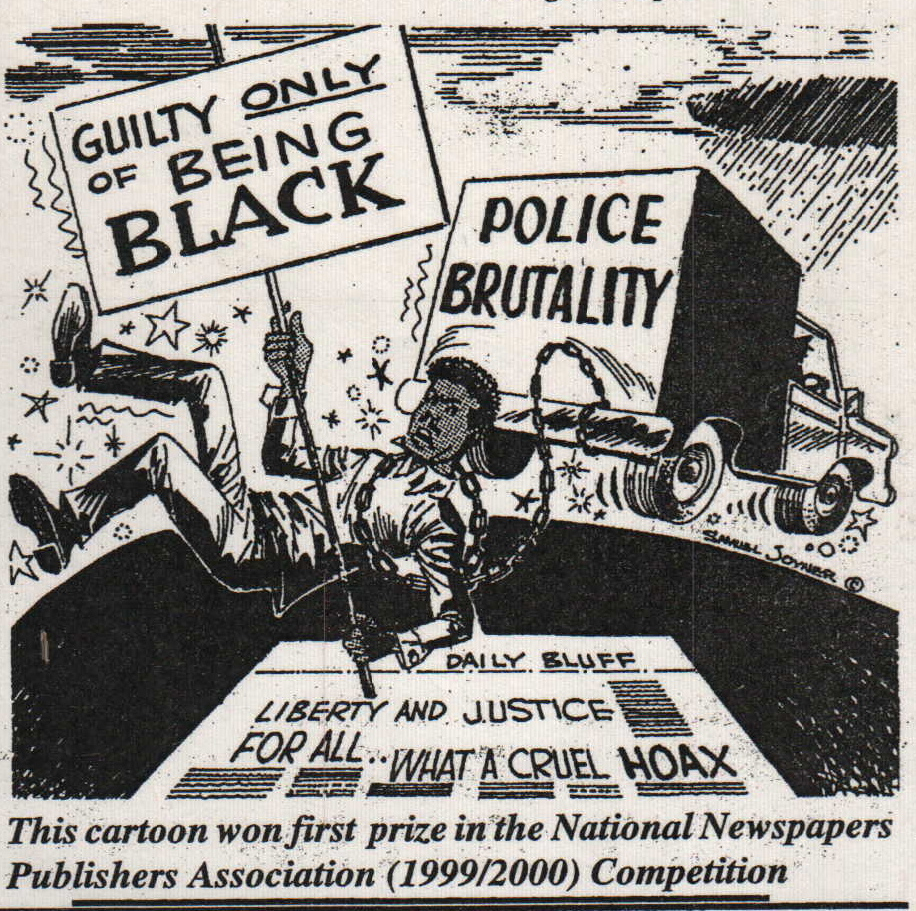

Ammon 2018]. Of the oral histories collected, Mr. Samuel Joyner’s

stood out as the kind of narrative that would have attracted Du Bois' attention.

Mr. Joyner, a retired artist, entrepreneur, World War II veteran, school teacher, and

regular church member, was among the first to sit down with us in his home to share his

story. Born in 1924, he described himself as a once-invisible artist who is now among

the few award-winning African American political cartoonists in the country. He was

surprised to find himself “out of place” in the North, a condition his family had

expected to escape when migrating from the South. Mr. Joyner’s segregated military life

in Alabama and the brutality of the South fueled his desire to use pen and ink to

confront racism, discrimination, and poverty. In his words, life in the South “made me

feel like dirt, you know. I had to walk out in the street when white people came.”

During World War II, when he discovered that the United States would feed white German

prisoners of war before feeding Black U.S. soldiers, he was left with a deep racial

wound. He confronted a similar kind of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism when he returned

North. Gifted and educated, Joyner still often gave his work to his white peers to pass

off as their own to ensure a fair wage for his work as an artist. Eventually, new

opportunities opened up, though they began as what he called "tokenism." In 1999, his

cartoon on police brutality earned

The Philadelphia Tribune a

National Newspaper Publishers Association award for best editorial cartoon (see Figure

11). His work has been archived at his alma mater, Temple University. We use his story to

highlight what Combs [

2015] refers to as the experience of being out of place both

geographically and symbolically (i.e., socially and politically) and the expectation of

assuming a subservient position to white people. Though Joyner did not find his place in the

military, he found his place of Black respectability at church and as an educator; he

also stumbled upon his place of Black resistance as a political cartoonist. These themes

can be heard as Joyner retells the ways he has confronted the problems of the color line

during his life (See Mr. Joyner’s oral history post including both videos and other

highlights:

http://www.dubois-theward.org/history/histories/samuel-joyner/).

The Participatory Research and the Role of Students and Teachers

Over 60 students have participated in the design and development of

The WARD. Through collaborations across the University of Pennsylvania and

other colleges, local high schools, and churches, we have involved students from the

fields of social work, history, urban studies, city planning, historic preservation,

political science, public health, education, and English [

Lowy 2011] [

Pirro 2012].

Students received training and engaged in a collaborative research process with faculty

and staff across Penn. By actively participating in each phase of the project, the

students came to understand the lived experiences of Black citizens within their social

environment and analyzed historical and contemporary racial patterns [

Kornbluh et al. 2015]. In the process, these students shared their knowledge, developed new skills, and

became empowered as co-researchers. Most notably, students collected archival records,

photographs, newspapers, and digitized manuscript census data from microfilm;

interviewed experts and community residents; produced documentaries; and designed the

board game, walking tour, and the high school curriculum materials. The project products

— particularly the Seventh Ward GIS, website, board game, walking tour guide,

documentaries, and oral history collection — are evidence of the research, analytical,

technological, and design skills that the students mastered and the creativity that they

brought to this project.

The board game (see Figure 12) provides a special example of how student artistic skills

and vision shaped many of

The WARD curriculum material. The

game requires players to assume the identity of one of eight Seventh Ward residents from

the 19th Century who represented the four social classes Du Bois included in his map. We

hired a student from a Philadelphia public high school as a research assistant who had

studied

The Philadelphia Negro in his required African American

history course, and he combed through the book for facts to include in the game card

questions. Jonah Taylor, then an undergraduate student, designed the board game based on

maps and historical photographs of the Seventh Ward. He gave the buildings a bird’s-eye

view perspective to add life to the game board, showing rooftops like Google Earth,

“playing off of contemporary visual culture” [

Taylor 2011].

To complement his computer-generated graphics, Jonah commissioned an art student at the

Maryland Institute College to paint full-length portraits of the eight board game

characters to incorporate into the game board and use for the game pieces. Using a

limited number of available photographs and conducting extensive research about late

19th century dress, Katie Emmitt produced multiple sketches and line drawings in order

to produce life-like oil paintings (Figure 13). “It was very difficult, and it was stressful,” she

explained in a video interview, “but it was such a good learning experience to have to

put all of my effort into making something that looked real,” [

Emmitt 2011]. The

original paintings include her lightly written notes in the corner to guide her

decisions about expressions and poses. For example, Mr. Turner, a member of the working

class who rented a room from Nettie Cook on South Darrien Street, had a common law

marriage to Katie, a white woman who worked as a maid. On his painting, Katie Emmitt

wrote “proud” and “tired face” in the top left corner.

Another undergraduate student research assistant, Heidi Smith, was frustrated by the

“moralizing tone” and the lack of voices of Seventh Ward residents in

The Philadelphia Negro text and primary sources such as the College Settlement

Association records. Borrowing an idea from late 20th century poet Charles Reznikoff,

she looked at transcripts from civil court cases to hear those missing voices and

developed poems based on individual court cases [

Bernstein 2014]. “I was wary that I

would be focusing on violence or crime, because that’s what court cases are mostly

concerned with and I didn’t want to give the impression that life in the Seventh Ward

had only to do with violence,” she explained in her project write-up. “I hope you will

look around and beneath the plot, to get at its implications, having to do with race,

class, gender, and language in really strange ways” [

Smith 2006]. One of the poems she

wrote told the story of how Mr. Turner, one of the board game characters, exchanged

heated words with another passenger on the trolley and then killed him in self defence

when the other man followed him off the trolley and into an alley.

High school students, college students, and teachers have embraced this project as a

novel way to recover and preserve the research of W. E. B. Du Bois and engage with a

part of the Black experience that textbooks rarely cover. Our collaborations have

extended to urban and suburban public schools, private middle schools, historically

Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), private liberal arts colleges, and a state

department of education. The curriculum has also expanded the opportunity to engage

students as co-researchers in this project. Through the curriculum, students learn to

apply social science methods as a tool for social change. Of particular note are the

assignments provided during the five days. On day one, students uncover the hidden

stories of a Black community once located in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward through a

19-minute documentary. On day two, students examine a range of historical primary

sources to learn and practice skills for analyzing documents to extract information and

identify patterns. On day three, students learn about social science research as a

systematic process of collecting information to answer questions about a community and

the potential role of research for social change. On day four, students play the board

game, and on day five, students use

The WARD’s GIS mapping

program to explore the spatial patterns of the historical Seventh Ward and learn about

specific individuals who once lived there. (See

The WARD

curriculum:

http://www.dubois-theward.org/curriculum/learning-goals/). This research

project has continued to evolve with feedback from teachers, high school students, and

college student researchers. Our student researchers continue to present new ways to

extend Du Bois' work while incorporating additional elements into the project. Like

many emerging digital humanities projects,

The WARD democratizes

the creation of this research and blurs the lines between the creators and users of this

research [

Ammon 2018]. This research project also extends the kinds of transdisciplinary

collaborations possible.

How Philadelphia and the Seventh Ward have changed

Once the largest Black community in Philadelphia, itself the Northern city with the

largest Black population at the turn of the 20th century, the Seventh Ward has lost most

of its Black residents even while the Black population in Philadephia has increased

ten-fold. The Black middle class was drawn to new row houses in West and North

Philadelphia — and to a lesser extent, the inner-ring suburbs — while lower-income

households found new opportunities in the segregated public housing developments across

the city [

Hunter 2013b] [

Hunter 2014]. Gentrification, broadly speaking, and the threat of a

crosstown expressway, specifically, led Black people to forgo Center City as the heart of

residential, religious, and cultural life. An area that was once 28% Black is now

dominated by upper-middle-class white people; only 7% of current residents identify as Black

or African American [

Du Bois 1899] [

U.S. Census Bureau 2018]. Numerous historic markers stand as

reminders of the lives and institutions of the Black communities in the Seventh Ward; memorialized

are the intellectual and activist Octavius Catto, the Institute for Colored Youth, and

Engine Company 11. At the edge of the Seventh Ward, Mother Bethel African Methodist

Episcopal Church — acquired by Richard Allen in 1794 — remains the longest-held Black

property in the nation.

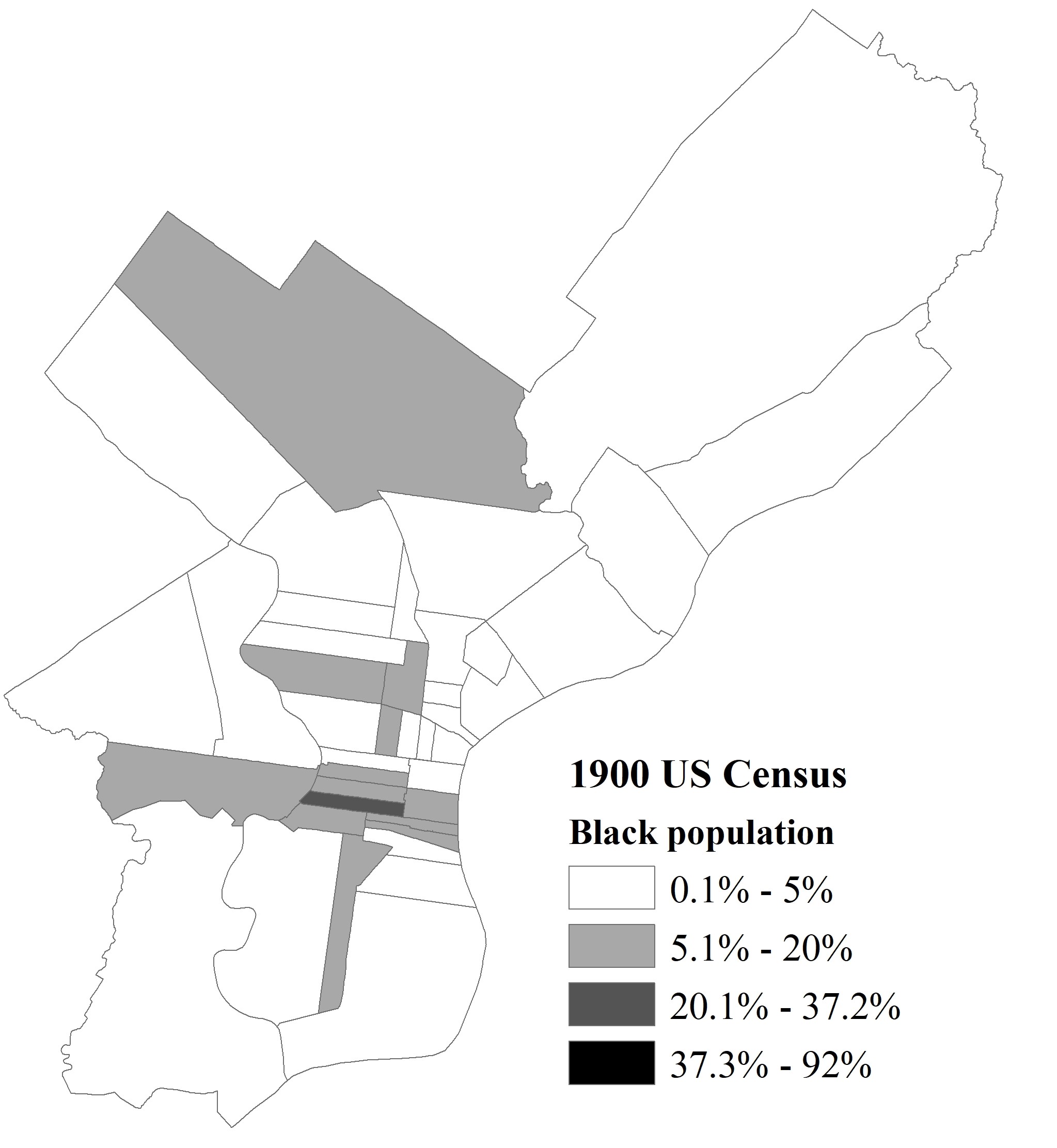

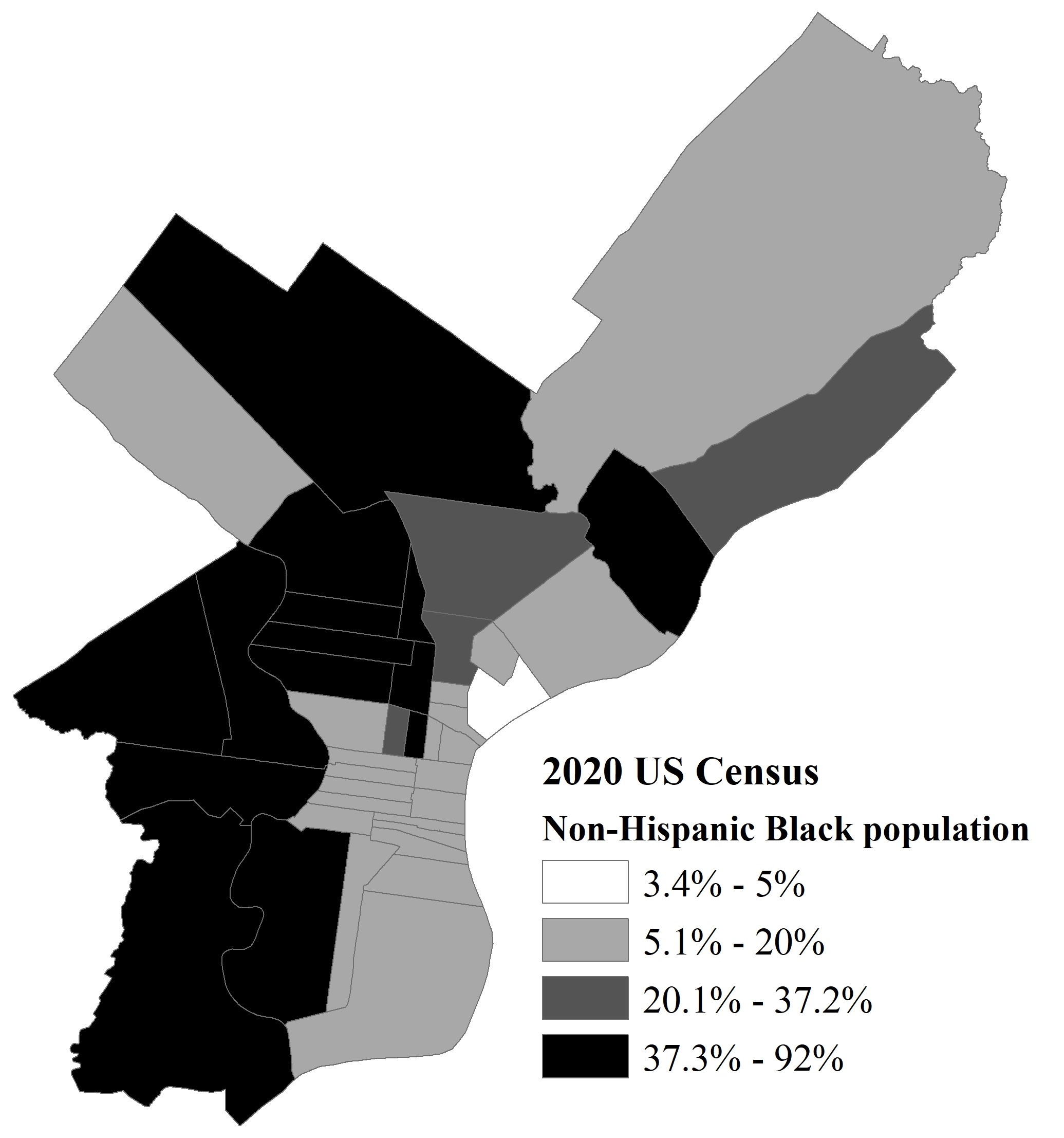

Maps comparing the distribution of the Black population in 1900 to that of 2020 show two

distinct patterns (see Figures 14 and 15). First, the Black population outnumbers white,

Hispanic/Latino and Asian groups. Second, Black people are concentrated in areas outside the

historical Center City and Seventh Ward, making up a majority of residents for a wide

section of the city stretching from due north of downtown to the far reaches of

Southwest Philadelphia. If one were to study the “Philadelphia Negro,” today, the

historical 32nd Ward in North Philadelphia might be the more appropriate focus. Anchored

by institutions such as Temple University and historic congregations such as the Church

of the Advocate and Zion Baptist Church. Racial residential patterns over the past 50

years have demonstrated a level of racial segregation unknown to people living in

Philadelphia at the end of the 20th century. Recent maps show how gentrification has

spread to neighborhoods north and south of the old Seventh Ward, further displacing

Black communities that once found refuge there [

Bowen-Gaddy 2018].

Limitations of The WARD

Despite the advantages that the 1900 U.S. census records provide over the original data

Du Bois collected, there are numerous limitations of this re-creation. Most importantly,

Du Bois gathered much more information than the census enumerators because his interview

schedules were more detailed, including questions about health, previous occupations,

experience with racial discrimination, income, housing, and neighborhood conditions. In

addition, the 1900 U.S. census was conducted three years after Du Bois conducted his

study, so there is no guarantee that it included the same people. Finally, a paid

enumerator — not a trained researcher of Du Bois' caliber — collected the census, so

the data are likely not of comparable reliability and validity. In fact, the

Philadelphia Press [Philadelphia Press 1900] reported in June 1900, while the census was

being collected, that two census enumerators were fired for drunkenness. Still, these

data provide the best approximation of Du Bois' survey results and offer great insight

into what Du Bois found when he came to Philadelphia — and how he conducted his

research.

The GIS re-creation of Du Bois' map indicates that the 2,500 households Du Bois

interviewed lived at approximately 1,400 properties. The property lines for the GIS

parcel layer do not correspond perfectly to the property lines on Du Bois' map,

primarily because they are based on different Bromley fire insurance maps. Also, some of

the properties that Du Bois marked as Black households had white residents in 1900,

according to the census. This was the case for at least 60 properties. Of the 1,400

properties, 70 appear to have been owner-occupied by Black people, consistent with Du Bois'

estimate that only 5% of Black Seventh Ward residents owned their own homes. We included

the walking tour and mural in this project as we recognize there is no substitute for

returning to the neighborhood and retracing Du Bois’ steps to discover what remains of

the Seventh Ward, particularly how this neighborhood helps us to understand the ways the

color line changed over time.

Conclusion

Through our digital humanities project, The WARD, we continue a

search to understand the universality and uniqueness of W. E. B. Du Bois' research. In

particular, we seek to document the patterns of the lives of Black people at the end of

the 19th century and compare those patterns to the experiences of Black people today.

Like Du Bois, we found that denying Black humanity takes many forms and ultimately

affects the place of Black people in education, employment, housing, civic life, and

other sectors.

Over 50 years ago, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Congressman John Lewis, and others

marching for civil rights, greater equality in voting, education, housing, and other

practices confronted firehoses, dogs, violence, verbal abuse, and even threats by the Ku

Klux Klan. Their courage helped to outlaw codified and sanctioned racist practices.

Today, students benefit from the progress made by changes in policies and practices in

voting, housing, education, and employment. They have, however, only pieces of the

racialized history pre-dating the Civil Rights movement to help them better understand

the world they inherited. This leaves them unprepared to fully understand the context

for the deaths of Black citizens during police encounters, challenges to voting rights,

and other problems of the color line.

The

WARD engages students in this research project to help them

remember our past and critically consider what they can do about the color line today.

Ultimately, we hope that revisiting Du Bois' work will help the next generation find

alternative ways of thinking about race and addressing both interpersonal and structural

forms of racism. The coronavirus pandemic and the police killing of George Floyd in 2020

have laid bare the persistent racism in our systems (e.g., persistent patterns of racial

segregation; limited access to health care, healthy foods, and reliable transportation;

concentrated poverty; lack of affordable housing) [

Williams and Cooper 2020] [

Yancy 2020]. These times call for community-engaged and participatory research projects like

The WARD to move us closer to our democratic ideal, one that

recognizes the full humanity of all people as created equal and endowed with the

unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2016 Institute for Space and Place

in Africana/Black Studies. The authors are grateful for comments from participants, the

peer reviewers, and Dr. Jena Barchas-Lichtenstein as well as the research assistance of

Rachel Williams, Sabrina Sizer, and Sonari Chidi. We also

acknowledge the generosity of our funders: The University of Pennsylvania’s Research

Foundation, Penn Institute for Urban Research, Robert A. Fox Leadership Program, and the

Provost Office; the National Endowment for Humanities; Philadelphia’s Samuel S. Fels

Fund; and the John B. Hurford ’60 Center for the Arts and Humanities at Haverford

College. We thank Baylor University librarians, Joshua Been and Sinai Wood, for creating a new interactive mapping dashboard for this project.

Works Cited

Ammon 2018 Ammon, F.R. “Digital Humanities and the Urban Built Environment:

Preserving the Histories of Urban Renewal and Historic Preservation.” Preservation Education & Research10: 10-30.

Aptheker 1997 Aptheker, H., ed. The Correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois, Volume 1. University of Massachusetts Press, (1997).

Battle-Baptiste and Rusert 2018 Battle-Baptiste, W. and Rusert, B. W. E. B. Du Bois' Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America. New York: Princeton Architectural Press

(2018).

Booth 1899 Booth, C. Life and Labour of the People in London.

London: MacMillan and Co.,

Limited (1899).

Bulmer et al. 1992 Bulmer, M., Bales, K., and Sklar, K. K. The

Social Survey in Historical Perspective, 1880-1940. New York: Cambridge

University Press (1992).

Carroll & U.S. Census Bureau 1894 Carroll, H. and U.S. Census Bureau. Report on Statistics of Churches in the United States at the

Eleventh Census, 1890. Statistics of Churches in the United States.

Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office (1894).

Combs 2015 Combs, B. “Black and Brown and Out of Place: Towards a Theoretical

Understanding of Systematic Voter Suppression in the United States.” Critical Sociology 42(4-5) (2015): 535-549.

Deegan 1988 Deegan, M. J. “W.E.B. Du Bois and the Women of Hull-House, 1895–1899.” The American Sociologist, 19(4) (1988): 535–549.

Deegan 2013 Deegan, M. J. “Jane Addams, the Hull-House School of Sociology, and Social

Justice, 1892–1935.” Humanity and Society, 37(3) (2013):

248–258.

Dorman 2009 Dorman, D. “Philadelphia’s African American Heritage: A Brief Historic

Context Statement for the Preservation Alliance’s Inventory of African American

Historic Sites” (2009):2–9.

Du Bois 1899 Du Bois, W. E. B. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social

Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press (1899).

Du Bois 1900 Du Bois, W.E.B. “The American Negro at Paris,” American Monthly Review of

Reviews 22(5) (1900): 575-577.

Du Bois 1903 Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. New

York: New American Library, Inc. (1903).

Du Bois 1968 Du Bois, W. E. B. The Autobiography of W.E.B. DuBois:

A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century.

New York: International Publishers. (1968).

Emmitt 2011 Emmitt, K. Video interview about process of painting board game

portraits. Philadelphia, PA, (2011).

Englander and O’Day 1995 Englander, D., and Rosemary O’Day. Retrieved Riches: Social Investigation in Britain, 1840–1914. Aldershot

Hants, England: Scolar Press (1995).

Gallon 2016 Gallon, K. “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities”. In Matthew K.

Gold and Lauren F. Klein (Eds.) Debates in the Digital Humanities

2016. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press (2016). pp. 42–49.

Hunter 2013a Hunter, M. Black Citymakers: How the Philadelphia

Negro Changed Urban America. New York, Oxford University Press (2013).

Hunter 2013b Hunter, M. “A Bridge Over Troubled Waters: W.E.B. Du Bois' The

Philadelphia Negro and the Ecological Conundrum.” The Du Bois Review

10(1) (2013): 7–27.

Hunter 2014 Hunter, M. “Black Philly After the Philadelphia Negro.” Contexts 14 (2014): 26–31.

Hunter 2015 Hunter, M. W.E.B. Du Bois and Black Heterogeneity. The

American Sociologist 46(2) (2015): 219–233.

Jones-Eversley & Dean 2018 Jones-Eversley, S. D. and Dean, L. T. “After 121 Years,

It’s Time to Recognize W.E.B. Du Bois as a Founding Father of Social Epidemiology.”

Journal of Negro Education 87(3): 230-245.

Katz and Sugrue 1998 Katz, M. and Sugrue, T.J. “Introduction” in Katz, M. and

Sugrue, T.J., eds., W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and the City: 'The Philadelphia Negro' and Its

Legacy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1998).

Kimball 2006 Kimbal, M. “London through rose-colored graphics: Visual rhetoric and

information graphic design in Charles Booth’s maps of London poverty.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication 36(4):

353-381.

Kornbluh et al. 2015 Kornbluh, M., et al. “Youth Participatory Action Research as

an Approach to Sociopolitical Development and the New Academic Standards:

Considerations for Educators.” The Urban Review 47(5)

(2015): 868–892.

Lane 1991 Lane, R. William Dorsey’s Philadelphia and Ours: On

the Past and Future of the Black City in America. New York: Oxford

University Press (1991).

Lewis 1993 Lewis, D. W.E.B. Du Bois : a biography / David Levering Lewis. New

York: Henry Holt and Company (1993).

Lindsay 1899 Lindsay, S. M. “Introduction,” The Philadelphia Negro:

A Social Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1899), pp.

vii-xv.

Loughran 2015 Loughran, K. “The Philadelphia Negro and the Canon of Classical Urban

Theory.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 12(2)

(2015): 249–267.

O’Connor 2009 O’Connor, S. “Methodological triangulation and the social studies of

Charles Booth, Jane Addams, and WEB Du Bois.” Sociation Today 7.1 (2009).

Philadelphia Press 1896 “Seeking Solution of Negro Problem,” The

Philadelphia Press. Susan Wharton Scrapbooks, 1894-1900, Historical Society

of Pennsylvania (1896).

Philadelphia Press 1900 “Will arrest census hater! Prominent man will test right of

enumerators to demand information,” The Philadelphia Press (1900).

Shuford 2001 Shuford, J. “Four Du Boisian Contributions to Critical Race Theory.”

Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 37, no. 3 (2001): 301–37.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40320845.

Smith 2006 Smith, H. “Notes on Testimony Sources.” Philadelphia, PA, (2006).

Taylor 2011 Taylor, J. Video interview about process of creating board game.

Philadelphia, PA, (2011).

Zuberi 2004 Zuberi T. W. E. B. “Du Bois’s Sociology: The Philadelphia Negro and Social Science.”

The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;595(1):146-156. doi:

10.1177/0002716204267535