Abstract

To date, there has been relatively little discussion of how the UK doctoral funding

landscape shapes digital humanities pedagogy for postgraduate research students. This

article sets out to address this relative lack, by introducing the inter- and

multi-disciplinary context in which many students in the UK work. We examine the

phenomenon of students who are not necessarily interested in becoming DH

practitioners, but have identified DH as a knowledge gap in their own disciplinary

practice. Such a realisation changes the nature of the learner within DH communities

of practice, requiring a different form of learning.

This study therefore explores learning within a community of practice, the inter- and

multi-disciplinary space in which digital humanities practitioners operate. First,

drawing on the diverse disciplinary landscape, it highlights an individual's learning

journey through self-determined learning (heutagogy). Second, it outlines an idea of

digital humanities pedagogy for postgraduate research based on current frameworks of

digital literacies and broader researcher development in the UK, framing research

activity as learning. Third, it presents the DEAR model for learning and teaching

design, which is based on four principles: Diversity; Employability; Application; and

Reflection. Finally, it provides an evaluation of the DEAR model in the context of

one UK Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP). It contributes to understanding of

pedagogical practices for doctoral-level DH training and provides a set of

recommendations for instructors to adopt and adapt these pedagogical principles in

their own programmes.

Introduction

Despite the growth of digital humanities (DH) centres and programmes during the last

twenty years, the provision of digital humanities training in the United Kingdom is

still unevenly distributed across universities and varies in format from dedicated

Masters and Doctoral programmes to more informal seminars and research groups. For

smaller or less research-intensive institutions, the establishment of a digital

humanities programme usually begins with the recruitment of a single specialist

lecturer [

Cordell 2016], who may however struggle to cover the breadth

of expertise required to provide suitably wide-spectrum teaching. While a number of

doctoral students may want to undertake a specific digital humanities PhD supervised

by a specialist, many may desire to acquire digital humanities skills without wanting

to specialise in the field and make it the centre of their research career. UK Arts

and Humanities PhD programmes are not as structured as their US counterparts, though

students are required to do a certain amount of training [

Nerad 2007]

[

Powell and Green 2007]. The direction of the training is left largely to the

students’ own choice; a form of “hidden curriculum”

[

Elliot et al. 2020, 20–1]

[

Thouaille 2017].

The provision of DH training at PhD level in the UK is shaped by the cyclical nature

of the funding context. Since the early 2000s, the funding of doctoral training in

the UK has moved away from single institutions or individual studentships towards

building multi-institution clusters. Initially focused on a regional basis, the

approach later moved to more multi-layered geographical models, with

research-intensive universities securing a prominent role in the new structures [

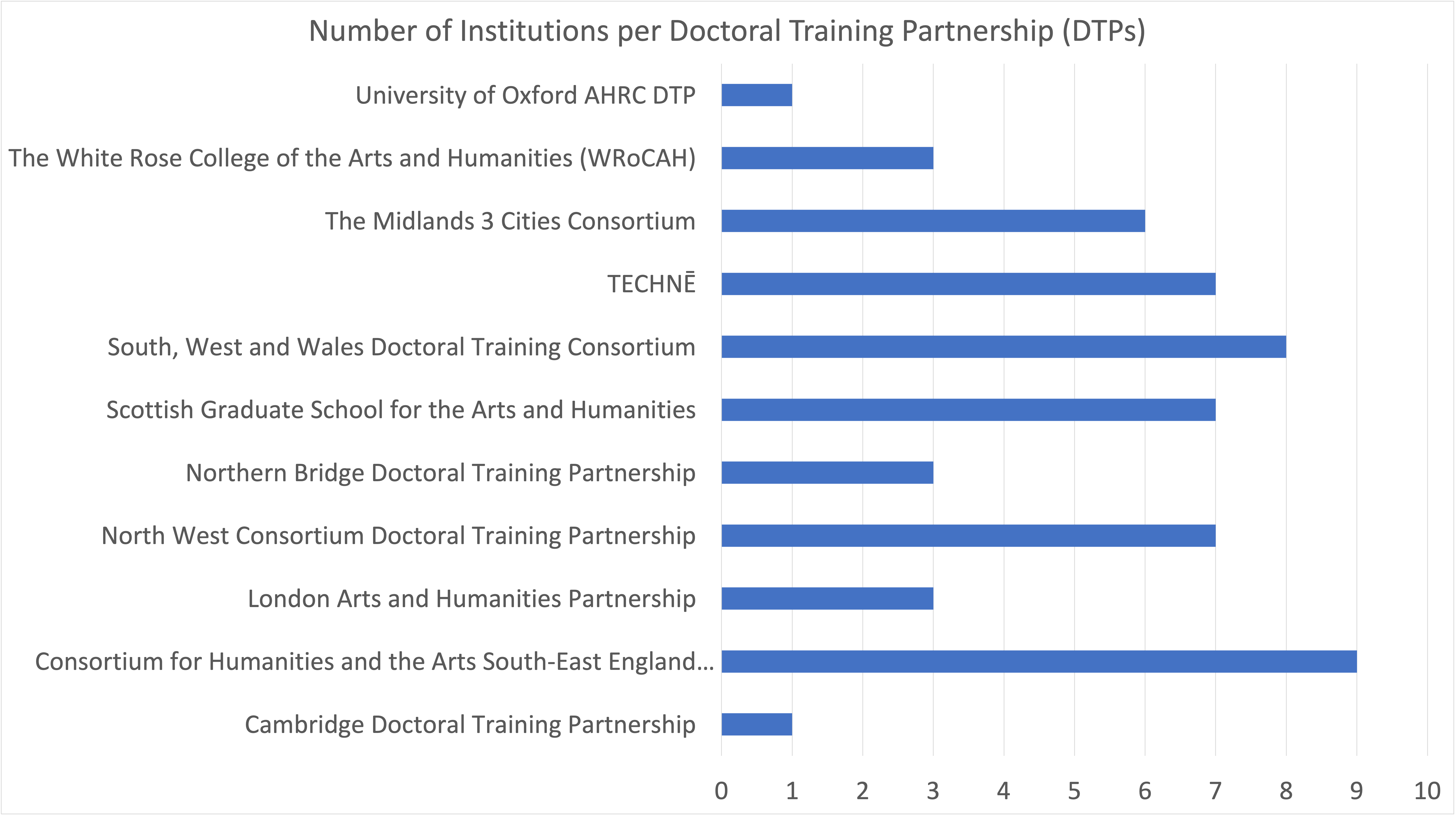

Harrison et al. 2016]. The eleven Doctoral Training Partnerships (DTPs) funded

by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) offer participating

universities the possibility of pooling the expertise of individual specialists to

provide more extensive coverage, especially in emerging areas such as DH (see

Figure 1).

One of the DTPs included in our survey is the Consortium of Humanities and Arts

South-East England (CHASE) DTP [

CHASE DTP 2020]. Founded in 2014 as part

of the DTP1 funding round, it initially comprised seven institutions: the

universities of East Anglia; Essex; Kent; Sussex; Goldsmiths, University of London;

the Courtauld Institute; The Open University. Two more joined in 2016: Birkbeck

College and the School of Oriental and African Studies. CHASE is now proceeding with

a revised membership for its DTP2 second phase, during 2019-2024. This research is

concerned with CHASE phase 1, the period 2014-2019, during which CHASE offered

seventy-five doctoral studentships per annum, enrolling a total of 373 students over

five years.

[1] This article will discuss the

implementation of a DH training programme in the CHASE DTP.

The provision of training is a central element of doctoral funding in the UK, in

keeping with the findings of the 2001 Roberts Review [

Roberts 2002] and

the 2010 Hodge Review [

Hodge 2010], which both recommended the

inclusion of skills training within doctoral education, with a particular emphasis on

transferable skills. From 2014 to 2019 CHASE employed its Cohort Development

Fund

[2] to initiate training

programmes in three broad areas: Advanced Research Craft, Future Humanities and

Public Humanities. Each year, a competitive bidding process allocated funding to both

staff- and student-led training programmes, leading to the development of a number of

initiatives. Once funding had been allocated and a programme established, students

were invited to apply for training places. During Phase 1 of the DTP, priority was

given to students in receipt of a CHASE studentship, while other PhD students at

CHASE institutions were usually allowed to apply if sufficient places were available.

Digital humanities was immediately identified as a priority area and regarded as an

essential element in the training opportunities offered to CHASE students. During

this period, the CHASE institutions displayed varying degrees of involvement with

digital humanities, ranging from the foundation of a multimillion-pound centre (the

Sussex Humanities Lab, launched in 2015), to the appointment of individual digital

humanities staff (Open University, East Anglia, Essex, Kent), to research and

teaching events on specific sections of DH or adjacent areas (such as Digital Media

at Goldsmiths, Digital Literary Studies at Birkbeck, Digital Art History at the

Courtauld). In none was digital humanities an established part of formal

undergraduate or postgraduate curriculum, though more informal training opportunities

were developed during the life of the consortium. While making it difficult for any

single institution to sustain a digital humanities training programme on its own, the

diversity of approaches and expertise present within CHASE had the potential to

provide a rich and diverse corpus of teachers.

This article introduces a new model of DH pedagogy (the DEAR model) and uses the

example of the CHASE Arts and Humanities in the Digital Age (AHDA) programme in the

context of the UK DTP framework. The AHDA programme was launched in 2015 by an

interdisciplinary team led by The Open University and the University of East Anglia.

It was allocated £15,000-£20,000 per annum by the CHASE Training and Development fund

to cover staff and student travel, seminar organisation and a certain amount of staff

time, with additional staff time provided as an in-kind contribution. It concluded

with the end of the first phase of CHASE in Summer 2019, after having trained over

one hundred students.

There have been previous approaches to training provision in digital humanities for

research students. The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded an

initiative for doctoral students in the UK called Collaborative Digital Research in

the Humanities (CEDAR) (2008-2010). It had three main aims:

- to further the understanding and expertise of doctoral students in the

humanities in the use of hypermedia and other digital humanities research tools;

- to bring together humanities doctoral students in a way that will ensure

current and future peer-led development in this area;

- to offer examples of good practice and innovation in the use of new

technologies in the humanities [Ensslin and Slocombe 2012].

CEDAR was a bold first step in the UK at creating inter-institutional training for

doctoral students on the eve of the creation of the Doctoral Training Partnerships.

However, the focus at that time was largely around how digital technology was

changing the ways that academics worked by sharing and modifying content. The depth

of understanding around the nature of data in the humanities, and the value of

quantitative and qualitative research methods, was at the time very limited.

Similarly, the Praxis Network project provides a snapshot from 2017 of eight

postgraduate-level programmes in digital humanities at institutions in the UK, US,

and New Zealand. The project aims to “emphasize new models of

methodological training and collaborative research”

[

Praxis Network n.d.] in the digital humanities. However, digital humanities

programmes are still relatively uncommon in the UK, and none has explicitly addressed

how the various motivations and expectations of participants shape the extent of

their desired participation in digital humanities as a community of practice.

We will therefore consider how DH training might be embedded within a student’s

broader learning journey with reference to the CHASE AHDA programme. First, we will

analyse how self-determined learning and working within a community of practice

combine in DH pedagogy to support heutagogical learning in DH. Second, we will define

digital humanities pedagogy in the context of postgraduate researcher training.

Third, we will introduce our model, the DEAR model, based on abstracted principles

from the applied pedagogy that could be adapted to account for locally informed

pedagogical practice. These principles are: Diversity; Employability; Application;

and Reflection. Fourth, we will demonstrate and evaluate how we have instantiated the

DEAR model into the CHASE Arts and Humanities in the Digital Age (AHDA) training

programme. In doing so, this paper will make a significant contribution to our

understanding of pedagogical practices for doctoral-level DH training by reflecting

on how the DEAR model can be adapted to other contexts, and provide a set of

recommendations for doing so.

Learning in a Community of Practice

The introduction of the DTP2 funding round (2019-2024) is changing the funding

context, making this an opportune moment to reflect upon DTP1. We therefore aimed to

provide a snapshot of the UK digital humanities provision at a time that coincided

with the end of the DTP1 five-year funding cycle. In June 2019, we surveyed data from

FindaMasters and FindaPhD, two of the most commonly used search websites for

postgraduate programmes. The syllabi of these MAs/PhDs were not examined, meaning

that this data refers only to programmes that explicitly mention DH. Of 350

advertised MA programmes, eleven could be identified as digital humanities. Of twenty

PhD studentships, only one mentioned both “digital” and “humanities.” It is

worth noting that most PhD scholarships are advertised in the period

October-December, so we conducted our survey during a time when fewer opportunities

would be on offer. However, even this survey suggests that digital humanities are not

explicitly mentioned in the majority of the programmes listed in the most widely used

MA/PhD search websites. Our brief analysis also flagged up different terminologies,

levels of self-identification and organisational alignment with digital humanities,

coupled with conflicting definitions of the field.

Another significant result of our survey was the geographical distribution of these

programmes. Of the eleven MAs advertised, eight were based in London, with the rest

of the country, especially England, being severely underrepresented (one course was

offered in Scotland and one in Wales). Only four of the eleven DTPs were included in

the offer of MA and PhD programmes in DH. Overall, this suggests that DH is rarely

the main focus of postgraduate learning in the United Kingdom. As a result, it is

important to reflect upon the challenge of providing DH training in a

multidisciplinary environment where students’ primary focus is at the subject level.

Whether English Language and Literature, History, or Art and Design, many students

ground their training needs first and foremost within their own disciplinary context.

It is therefore important to their development to understand how disciplinarity has

been addressed within the digital humanities.

Inter/multidisciplinary

To take into account the broad disciplinary perspectives of our students, we have

sought not to centre our pedagogical approach on a strict definition of the

digital humanities. In this we take our lead from scholars such as Lisa Spiro, who

describes the digital humanities as a “convergence of several

sets of values, including those of the humanities; libraries, museums and

cultural heritage organizations; and networked culture”

[

Spiro 2012]. All of these groups have been represented in the CHASE

AHDA programme, and each faces the challenge of defining how their established

practices relate to the inter- and multi-disciplinary communities that constitute

DH. In 2011, Matthew Jockers and Glenn Worthey coined the highly influential

concept of the “Big Tent” to express the diversity of DH practices, noting

their “wonder and appreciation for the many-splendored field

of DH”

[

Jockers and Worthey 2011] in a move that was designed to be highly inclusionary

and participatory. Simultaneously joyful and pragmatic [

Terras 2011], the big tent also had the unintended effect of erasing the multifarious

disciplinary traditions – effectively grouping everybody into a single amorphous

space which, by erasing the barriers between disciplines, in fact worked to ensure

that traditionally powerful scholarly traditions dominated the conversation.

Klein (1990) has noted that interdisciplinarity

relies on some form of demarcation between the disciplines in question, and the

push back against the unintended erasure of smaller disciplinary traditions via

the big tent has been characterised by a similar logic.

Klein, while recognising the broad scope and significance of interdisciplinarity,

notes that cutting across all the various theories is one recurring idea: that it

“is a means of solving problems and answering questions

that cannot be satisfactorily addressed using single methods or

approaches”

[

Klein 1990, 196]. The extent to which the digital humanities

truly engage with various disciplines has been contested [

Liu 2013],

and indeed attention has fallen in recent years upon how it represents and

exchanges knowledge with other meta-disciplines such as Library and Information

Studies [

Gooding 2020].

This view follows on from McCarty and Short’s work to map the extent of humanities

computing, the forerunner term to digital humanities. Their work resulted in the

creation of a “methodological commons” which presented

DH as a series of convergence points between the various disciplines, and focusing

upon methods and tools that were considered essential to the DH community [

Siemens 2016]. The nature of this collaboration, or this community of

practice, in DH has been heavily discussed over the years. Several models have

been introduced, which expand upon or provide alternatives to Melissa Terras’

notation of the concept of communities of practice [

Terras 2006].

Terras considered whether or not digital humanities (as we now understand it) was

actually a discipline or a community of practice. The former has a more

institutionalised presence as well as an international community; the latter, a

group “which shares theories of meaning and power,

collectivity and subjectivity... but is little more than a support network for

academic scholars who use outlier methods in their own individual

fields”

[

Terras 2006]. Terras’ conclusion is that digital humanities seems

to act like a discipline, but without the institutional acceptance of a subject:

“...the community exists, and functions, and has found a

way to continue disseminating its knowledge and encouraging others into the

community without the institutionalization of the subject”

[

Terras 2006].

This desire to encourage others to participate effectively in DH has led to a

great deal of work in relation to the nature of these communities of practice. In

his influential account, Ray Siemens ruminates on the careful balance that must be

found between preserving an element of disciplinarity, on the one hand, and

adopting a more revolutionary approach to DH:

When we do

try to define in a way that can lead to action...there’s a loss via

disciplinarity’s constraint in light of current and future growth, narrowing

potential collaborative opportunities… Conversely, we can choose to ignore

disciplinary and institutional structures, adopting the revolutionary

approach we find reflected in the several excellent manifestos existing in

the area… but, in ignoring those structures, we run the risk of losing

access to their benefits.

[Siemens 2016]

Siemens, however, focuses upon the

collective nature of this relationship, arguing that this community contains

people who have “identified”

[

Siemens 2016] with the community of practice. The notable and

admirable focus on collectivism here, then, begins to build a definition for DH of

those who are a self-selecting part of the recognised DH community. Within this

context, Siemens’ repeated discussion of the term “we” - “who we are via what it is we do, where we do what we do, and why we do it in

the way that we do it”

[

Siemens 2016] becomes a carefully constrained collective that may

even have limited relevance to those who do not want to identify with the DH

community. Yet, as we have found through our training programme, the

non-identifying DHer represents a significant proportion of those reaching out for

relevant training. Thus it is essential for us to consider how other models – of

DH, of pedagogy, and of learning – might support such learners to engage with

critical digital humanities practices in a meaningful way, by which we mean in a

way that can be successfully operationalised in the individual’s own work.

Svensson borrows the notion of “trading zones” to

describe “places where interdisciplinary work occurs and where

different traditions are maintained at the same time as intersectional work is

carried out”

[

Svensson 2012]. He argues that the digital humanities can become an

intersectional meeting place where scholars can maximise points of interaction and

facilitate deep praxis-led interactions. However, as

Terras (2006) notes, we are still talking here primarily about a

research environment rather than a learning environment. What we are often doing,

then, is encouraging students to enter the DH space through meta-debates that are

focused upon effective research rather than effective learning. Indeed, Claire

Warwick has challenged the orthodoxy assuming that a single form of DH will emerge

that encompasses all relevant parties, noting “the likelihood

that different schools and methods of doing DH will emerge”

[

Warwick 2016]. What, however, is most relevant to the discussion of

research training is that despite their importance to the field of DH,

meta-debates are not obvious to newcomers, and are indeed not often relevant.

Instead, we have found through the CHASE AHDA programme that the key sticking

point for many participants is working out how to operationalise new forms of

intellectual and technical practice into their existing humanistic modes of study.

As such, the otherwise essential work on communities of practice emphasises

characteristics of collectivism in DH research that are to some extent

incompatible with the more self-directed individual learning journey that many new

entrants to DH embark upon.

Interdisciplinary learning, though, offers a degree of guidance in navigating this

tension between the community and the individual learner. Indeed, we will argue

that groupwork is essential within this individual learning journey in order to

expose learners to other disciplinary perspectives, and is a key facet of learning

in this context. Klein’s notions of the pedagogy of interdisciplinarity, for

instance, share an intellectual core with the structure of the CHASE AHDA program.

For instance, she notes that both DH and interdisciplinary learning are “active and dynamic. Group work and projects are common and,

echoing the constructivist theory of learning, students build new knowledge

through exploration and the actual ‘doing’ of a subject”

[

Klein 2014]. Many existing training programmes emphasise and

reinforce the idea that there is a core set of competencies and methods that are

central to DH. This is a matter of necessity, but one great strength of the

collaborative doctoral training system in the United Kingdom is that it encourages

interdisciplinary and collective solutions from staff that support individual

learning from learners.

Digital Humanities and Self-Determined Learning

Many of our students on CHASE AHDA have been more focused on their individual

learning journey. Indeed, the programme has welcomed the full spectrum of

attendees from those who intend to pursue DH-related careers, to those with an

interest in learning more about the field, through to those who are solely

interested in how to operationalise and understand specific DH competencies in

their own work. This means that individuals must learn about the methods and tools

that are available to them, how they individually relate to DH, and how that

influences their own learning. We turn here to the literature on self-determined

learning to propose that it must sit alongside community-driven active learning in

order to maximise the benefits to participants from diverse backgrounds. Our model

for CHASE AHDA thus emphasises two key points: self-determined, reflective

learning, and scaffolding of sessions via active learning and groupwork. As we

will outline here, this allows learners to create their own learning communities,

not as spaces for research practice, but as networks to facilitate and support

their own individual learning approaches. To this end, the concept of heutagogical

learning has been largely underexplored in relation to DH pedagogy.

The term heutagogy was introduced by

Stewart Hase and

Chris Kenyon (2000) to represent the study of self-determined learning.

They draw upon Knowles’ definition of self-directed learning as:

The process in which individuals take the initiative, with or

without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating

learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning,

choosing and implementing learning strategies, and evaluating learning

outcomes .

[Knowles 1970, 7]

Importantly, though, they view

heutagogy as a less linear, and more intuitive and unplanned process. Hase and

Kenyon emphasise that heutagogical learning emphasizes flexibility, in that the

teacher provides resources but the learner designs their own course and, if

appropriate, the assessment [

Hase and Kenyon 2013]. A heutagogically-centred

approach for DH, then, relies upon the ability of learners to access resources

with relevance to their own learning, and to develop their own journey through the

material in a way that helps them to define and obtain their own desired outcomes.

While structured workshops play a vital role in imparting often highly technical

information to learners, and do so within the CHASE AHDA programme, it suddenly

becomes hugely important to provide a highly reflective space that allows learners

time to consider these aspects of their learning. The question of reflection has

been under-investigated but not ignored in DH pedagogy. Mahony et al. provide a

valuable account of the role of reflection in Masters’ study, for example [

Mahony 2014]. The focus and value here is around doctoral learning,

which should address higher-order thinking, and ultimately support an original

contribution to knowledge, a key tenet of research degree programmes in the UK,

and arguably worldwide [

Quality Assurance Agency 2020]. Heutagogy, within this context,

represents a shift towards the learner that facilitates such a reflective turn.

In a subsequent article, Hase noted that heutagogy:

suggests that learning is an extremely complex process that occurs within

the learner, is unobserved and is not tied in some magical way to the

curriculum. Learning is associated with making new linkages in the brain

involving ideas, emotions, and experiences that lead to new understandings

about self or the world.

[Hase 2011]

While much of the heutagogical literature

refers to online learning, it is characterised by several aspects that provide a

useful framework for student-led learning in DH: self-determined learning, in

which individuals take the initiative to diagnose their learning needs and engage

with resources in a way that leads to new understandings [

Hase 2011]; group collaboration, via active learning and creation [

Blaschke 2013]; and a reflective approach to identifying and

evaluating learners’ own learning outcomes. These all provide a useful pivot point

that aligns the approach of the CHASE AHDA programme more closely with those

models of DH that emphasise not only communities of practice that have been

discussed here, but the ways in which diverse individual and disciplinary

backgrounds inform how participants approach their learning in DH.

As such, while DH emphases the collaborative, the interdisciplinary, and the

community-driven aspects of its praxis, its training is often centred on a

self-determined journey of discovery. Stories abound of the autodidact in DH, the

individual who was forced to teach themselves due to a lack of external training.

There is an element of necessity in this – while many aspects of method, approach,

even theory, can transfer across the disciplines that represent the DH community

of practice, a new entrant is faced with the challenging prospect of working out

how to apply these myriad contexts to their own work. It is therefore essential

for them to be given the space to reflect upon their own journey, to adopt a

heutagogic approach to their learning that helps them to shape and decide their

level of engagement with the research-focused community of practice that sits a

step beyond the methodological commons of DH practice situated within various

disciplines.

Yet, as DH training becomes an ever-more embedded, but sadly under-theorised, area

of focus for the community, the question of how to balance the needs at the

various points of the learner spectrum becomes a highly pressing concern. As the

following section will indicate, the framework outlined here gives us a structure

upon which we, as professionals with DH-related positions, might leverage our

broader understanding of the field in a way that promotes the self-determined

model of learning that is necessary to support a diverse body of learners.

Digital Humanities pedagogy in the context of postgraduate researcher

training.

In addition to the tension between collectivism and individual direction in

research practice, there is a further layer of complexity as this takes place

within specific higher education structures. The increased formal presence of DH

in universities and DTPs has an influence on who attends certain training

programmes. Where there is a strong local presence of DH, students are likely to

use that provision first, as opposed to a cross-institutional programme provided

by the DTP.

A digital humanities pedagogy for research training therefore needs to be mindful

of the quasi-disciplinary community it speaks to and the ability of students to

apply skills and behaviours locally within their own institution. This will depend

on the degree to which DH has been embedded alongside the other fundamentals of

their discipline. One of the dimensions that has been crucial in the DTP training

context is employability. For example, the CHASE DTP currently provides students

with the opportunity to undertake a three-month paid internship with a partner

organisations in the GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) sector [

CHASE DTP 2018]. As a result, students are coming to programmes such

as the CHASE AHDA with objectives that include enhancing future employment

prospects [

Software Sustainability Institute 2020].

The primarily US-oriented literature has addressed such learner motivations.

Leigh Bonds (2014), for instance, has written on the

preparation and delivery of undergraduate courses that include both the

employability dimension, which is also a feature of researcher development, and

“project-based learning;” an approach relevant to

our model of training.

Margaret Konkol (2015),

however, has highlighted some of the inherent assumptions around learning and

research outputs around digital humanities in US institutions (and arguably those

in the UK as well). The difference that Konkol identifies is the apparent

distinction between the two terms: “digital humanities” and “digital

pedagogy,” in which the latter is “classified as the

light and lively little sister whose ability to use digital tools in the

classroom engages students in a variety of interactive learning formats”

[

Konkol 2015].

Konkol’s digital pedagogy resembles digital literacies in the UK (

Figure 2); functional skills aimed at employability

which can be readily embedded in undergraduate programmes, with defined learning

outcomes. However, research activities that may receive more substantial funding

tend to sit apart from learning and teaching conceptually. The “real”

academic work is assumed to take place within such projects.

In many ways, universities and digital humanities teachers can draw on a digital

literacy framework in the UK to structure their approach, but the functional

skills, such as learning Python syntax to extract textual data from different

source files (ICT literacy), are not in isolation training in digital

humanities.

Digital literacies are defined by JISC as “those capabilities

which fit an individual for living, learning and working in a digital

society”

[

JISC 2014]. Although frequently considered in relation to

undergraduate and Masters programmes, which are highly structured through taught

programmes, they are clearly applicable to researchers, and particularly those

whose work focuses on or utilises digital resources.

These seven elements have a clear employability dimension, and are intentionally

transferable from the formal learning environment of the university classroom, to

other sectors and industries. They are also compatible with the recommendations of

research training formulated since the 2002 reviews [

Roberts 2002]

[

Hodge 2010], and they also map onto several subdomains of the Vitae

Researcher Development Framework (RDF) (

Figure 3),

namely Knowledge Base (A1), which comprises information seeking, literacy and

management, as well as Professional and Career Development (B3) and Working with

Others (D1).

The challenge for those in the UK who support doctoral researchers is to develop

these digital literacies across a range of disciplines and fields at a research

level, rather than embed them in undergraduate programmes.

One of the reasons that the pedagogy around digital literacies is so challenging

is that it contains seven elements that work as part of a longer developmental

process, and one which is seen as very much bound up with the student’s own

identity [

JISC 2014]. Research training as a whole can be seen as

remedial, with digital literacies becoming part of a deficit model in higher

education [

Hinrichsen and Coombs 2013], the aim being to embed functional

skills to enable the student to complete their research in a timely fashion, and

hence reduce risks around non-completion and low employability. This has been a

particular concern in doctoral education in the US in recent years [

Rogers 2020]

[

Cassuto and Weisbuch 2021].

Konkol’s point here is that this distinction is false. Digital humanities work

entails learning, (few researchers begin research fully-equipped to undertake it)

and students can learn through involvement in and contribution to real-world

projects: this is how a digital humanities pedagogy is applied. In short, and in

the applied context of research training, we have taken digital humanities

pedagogy to mean digital humanities combined with digital pedagogy.

Core Elements of a Digital Humanities Pedagogy

Reviewing the last decade of digital literacies and digital humanities

pedagogy, it is clear that researcher developers need to look broadly at the

context of the modern doctorate, the design of undergraduate teaching using

project-based learning, digital literacies, employability, and the nature of

digital humanities as a community of practice to inform the structure of formal

programmes. The CEDAR programme mentioned earlier focused primarily on digital

literacies, whereas there is a need for a model that encompasses the complexity

of postgraduate researcher training. CEDAR encountered challenges around the

diversity of backgrounds of students, which reflects Taylor, Kiley and

Humphrey’s [

Taylor et al. 2018] observation about the present diversity

of the doctoral candidate population worldwide.

In drawing together these phenomena at research degree level, we can discern

several core principles:

- Programme design should embrace diversity of candidates’ a) disciplinary

backgrounds and b) technical proficiencies

- Learning outcomes should reflect candidates’ priorities around

employability, in terms of transferable ICT skills and disciplinary

expertise

- Learning should emphasise application and preferably involve the design,

execution and evaluation of a project

- Learning should emphasise reflection on a) individual abilities and b)

attitudes and behaviours towards others in the digital humanities

community

We can visualise these principles as core elements to underpin learning and

teaching, which we present in

Figure 4 as the

“DEAR” model:

Although there are clear challenges to embedding each of these elements, they

should function and be taught interdependently. For example, significant

differences in technical proficiencies (diversity) can be supported and

improved through initial reflection by candidates on their current abilities

and aspirations (employability), as well as the nature of the application; most

projects do not rely on all team members having the same skill sets, nor do

individual projects require an individual to have a high level of proficiency

in all skills. The skills and competencies need to match the

aims of the project. This is true of any doctoral research; digital

humanities projects are no exception.

In the following section we will consider how this self-determined approach to

learning and engagement with a community of practice supports a digital

humanities pedagogy. We will do so with reference to the CHASE AHDA programme,

which embodies many aspects of the pedagogical DEAR model proposed here.

The CHASE AHDA programme

This section demonstrates and evaluates how the principles of the DEAR model were

instantiated in the CHASE AHDA programme. The programme was enabled by a yearly

grant from the CHASE Training and Development Group, which was allocated each year

during the period 2014-2019 through a competitive bidding process. The grant

covered staff travel and subsistence while teaching on the programme, catering for

staff and students and honoraria for a small number of external speakers. Staff

time and room use were provided as an in-kind contribution from CHASE member

institutions. No charge was levied for enrolling in the programme, but students

were responsible for their own travel costs, except for overnight accommodation at

residential workshops, which was covered by the yearly grant. Students who

received their doctoral scholarship from CHASE had access to a £1,000 individual

research allowance, which they could employ to travel to the course workshops.

The first iteration of AHDA in 2014/15 experimented with a multi-site approach

based on independently-held seminars on a number of Digital Humanities subjects,

which experienced quite variable levels of attendance. While each seminar provided

in-depth training on a given area, the CHASE Training and Development Group

remarked upon the lack of a unifying vision for the programme. In order to address

these issues, the core AHDA team, led by Francesca Benatti (Open University),

Matthew Sillence (University of East Anglia) and Paul Gooding (then University of

East Anglia) decided from 2015/16 to provide a more directed programme delivered

in one centralised and easily accessible location, The Open University in London

regional office. After Paul Gooding’s move to the University of Glasgow, David

King (Open University) joined the core AHDA team for the 2018/19 academic

year.

The emphasis of the revised programme was to provide a more coherent structure

with clearly defined outcomes in terms of employability skills, allowing space for

the application of DH research skills within a short project. At the same time,

students would be invited to reflect upon their degree of participation in the

digital humanities community, taking into account the diversity of their

backgrounds and goals. The structure of the course was therefore revised and

rebuilt around

- a three-day residential winter school (December or January)

- four one-day methods-based workshops (January - April)

- a two-day mid-project residential (March)

- a final plenary session (April or May)

Below we assess how the programme employed the DEAR pedagogical model to achieve

its outcomes within the remit provided by the CHASE DTP.

Winter School

The 2014/15 iteration of the AHDA programme had shown the promise and

challenges of digital humanities training. Following informal consultations in

2015 with Digital Humanities colleagues and with the CHASE Training and

Development Group, it was decided to open all following presentations of AHDA

with a three-day residential Winter School, which took place in December or

January. The aim of this intensive residential opening was to enable the

students to reflect upon their prior knowledge of Digital Humanities and their

expectations for the course. In addition, a venue was provided for students to

begin to consider their desired degree of participation in the digital

humanities community. A public blog was maintained for each year, providing

information on programme details, booking links, and access to learning materials

[3]. Over its four iterations, the Winter School was attended by fifteen to

twenty-five students each year, with numbers capped at twenty students per

programme from 2017/18 onwards. The event consisted of

- a plenary lecture by leading CHASE Digital Humanities scholars

- a number of introductory 2-hour seminars from the AHDA core team and from

the teachers of the subsequent workshops, including

- Digitisation and metadata

- Text analysis

- Data visualisation

- Image analysis

- Threshold concepts as a critical learning framework

- Project management

- a final student-led “unconference” focusing on the practical group

project that would form the main application of their learning

The residential school format has widespread precedents in Digital Humanities

pedagogy, such as for example the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI)

[4] and the Digital Humanities at Oxford Summer School (DH@OxSS)

[5]. For the AHDA programme, it was found to offer considerable benefits

but also some significant disadvantages, due to the diversity of the student

population. An intensive, face-to-face experience allowed the students to

participate in a more in-depth introduction to the variety of Digital

Humanities approaches. Additionally, it permitted students from different

universities and departments to develop connections based on common or

contiguous interests, building a sense of membership in a shared student

cohort. Finally, it was central to the definition and allocation of group

projects, which formed a central part of the application of the students’

learning.

The four iterations of the Winter School confirmed the validity of this

approach but also highlighted its exclusionary impact on certain categories of

students, with the potential to negatively affect student diversity.

Specifically, students with disabilities, caring duties or additional

commitments (for example, those undertaking part-time study) were found to

experience difficulties in attending the Winter School or in committing to its

full duration. Mitigation strategies were gradually put in place and included

the prior circulation of teaching materials and handouts, culminating finally

in the video capture of the directed teaching component of the School from

2017/18 onwards. However, the seminar-style discussions and group-based

exercises could not be captured for data protection reasons.

Contents were pitched at an introductory level, assuming no prior familiarity

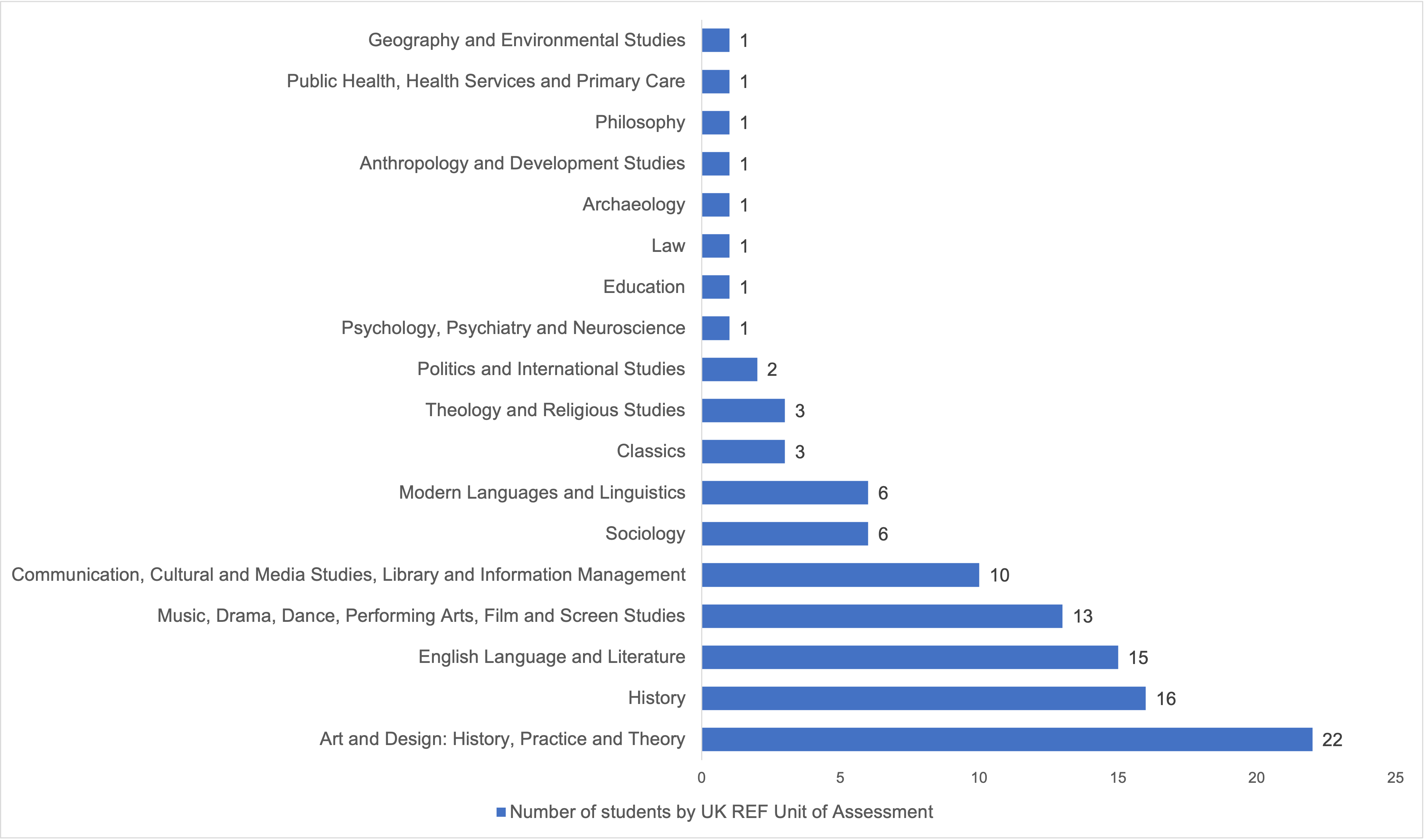

with Digital Humanities methodologies and debates. The diversity of the student

cohorts was the main reason for this choice. While CHASE is a specialist Art

and Humanities partnership, student backgrounds were nonetheless quite

disparate, including a range of subjects such as digital humanities,

musicology, practical digital arts, social sciences, literature, art history,

history, visual arts/visual anthropology and media studies.

Figure 5 groups them on the basis of the UK

Research Excellence Framework (REF) Units of Assessment

[6].

Though a growing number of students joined AHDA because of an interest in

digital media and culture, over the five iterations students presented with

variable levels of digital skills, ranging from programming to video editing to

basic digital literacy skills. Rather than force the more novice students to

catch up on their own, the Winter School was designed to develop a common basis

through intensive training. Topics discussed included what were labelled “the building blocks of Digital Humanities:”

digitisation and metadata, basic text analysis and web authoring. All topics

were taught in two-hours sessions, which included both a lecture and a

practical applied component through in-class exercises. The exercises, carried

out in small groups, offered a first chance for students of different prior

skill levels to enter into a dialogue and begin to collaborate.

Transferable skills for employability were further developed with the

introduction of a session on project management from 2017/2018 onwards.

According to a recent report, unlike their colleagues in STEM, UK Arts and

Humanities PhD students are less likely to be motivated to undertake doctoral

study by the opportunity to develop transferable skills [

Bennett 2020], despite the fact that roughly 75% of those who move

into non-academic careers undertake non-research roles [

Hancock 2020]. The CHASE AHDA team therefore viewed it as

essential to introduce students to the skills that could be mapped to Domains C

and D of the Vitae Researcher Development Framework, especially around Research

Management (C2) and Working with Others (D1) (see

Figure 3). A half-day project management workshop was delivered in

collaboration with the British Library, one of the CHASE non-academic partner

institutions, and by CHASE team members with project management expertise. In

2019, we also partnered with the Royal Society, the School of Advanced Studies,

and digital consultancy company Digirati to provide a workshop to evaluate the

Science in the Making platform, where students worked alongside cross-sectoral

partners to support further development of the user interface and functionality

of the resource.

[7]

A significant reflective element was provided by a session on threshold

concepts, which asked the students to consider the motivations and modalities

of their learning journey [

Kiley and Wisker 2009]. Through threshold

concepts, students were asked to examine the process of learning, focusing on

their expectations of transformative and integrative enhancement to their

education through their participation in AHDA [

Berman 2013]. The

decision to include this component was led by research showing the benefit of

aiding students in the development of an explicit conceptual framework to

support doctoral learning [

Berman 2013]. At the Winter School,

students were asked to define their research problems and to organise their

research design for the upcoming group or individual project, with further

assessments of their implementation and their conceptual conclusions in the

middle and at the end of the entire AHDA programme. They were also asked to

situate their participation in AHDA within their broader learning and career

goals.

The Winter School was designed to allow the students to combine an individual

learning journey with taking the first steps into a digital humanities

community of practice. After the 2016/17 academic year, teacher-led plenary

sessions were replaced with presentations from AHDA alumni who evaluated the

programme and its impact on their employability, for example by enabling them

to join Digital Humanities projects as interns or team members. This

heutagogical approach culminated in a one-day student-led “unconference,”

during which students were asked to propose a research project, usually focused

on their own research interests, and to pitch it to their fellow students.

Votes were then cast to choose which four projects would be developed during

the remainder of the AHDA course, with students choosing which project group to

join. AHDA team members then provided the students with advice on methodologies

and resources for their projects.

While this process enabled students with more developed plans for their

learning journey to expand them through the help of their peers, feedback

collected over the first three iterations led to the introduction of individual

projects. The latter were found to enable greater dialogue between the

interdisciplinarity of Digital Humanities methods and the diversity of the

students’ disciplinary backgrounds and interests. This grounding in the

students’ own priorities helped them to remain motivated for the duration of

the programme and to assess the relevance of their learning to their future

employability. The initial presentation and the subsequent iterative refinement

of the project ideas through peer and teacher feedback were retained even with

the individual projects approach.

Follow-on workshops

After the Winter School, students had further opportunities to self-direct the

course of their learning. Between 2015/16 and 2017/18, students were able to

choose between two and four one-day workshops, held face-to-face over the

course of three months (January to April). The syllabus as initially proposed

aspired to provide an overview of the main areas of Digital Humanities research

as as reflected in the expertise present within scholars from CHASE and the

British Library, who delivered workshops on the following topics:

- Text Analysis for History and Literature

- Digital Images and Digital Art History

- Databases

- Information Visualisation

While the topics above were appreciated by the students, they were not equally

relevant to all of the students’ diverse disciplinary backgrounds and to all of

their employability goals. This element of self-direction led to an excessive

dispersion of a small student cohort, with certain seminars being poorly

attended. More broadly, it reduced the development of a common grounding in

digital humanities methods and perspectives.

The emphasis of the AHDA programme shifted gradually from teaching discrete

topics into preparing the students for employability as digital researchers

either as individuals or as part of a group. The 2018/19 programme focused

therefore on guiding the students through the development of their own research

project, providing workshops on the following interdisciplinary skills:

- Data cleaning and management

- Introduction to Python

- Network Analysis

- Information Visualisation

Each workshop included a taught element, presented by a subject specialist, and

a practical afternoon session, where students applied what they had learnt to

their individual projects and data. This hands-on session enabled students to

ask and receive advice from the AHDA team, who were also available outside of

the workshops through virtual office hours. The diversity of the student cohort

resulted in all students being able to make contributions to the discussions

and exercises on the basis of their disciplinary and personal background, such

as having experience of working in cultural institutions, being skilled in a

programming language, or being familiar with certain media types.

Mid-project residential

Another residential event was organised midway through the AHDA programme,

usually in early March. Students and the AHDA team met for two days to

- report on project progress in 10-minute individual or group

presentations

- receive feedback and “feed forward” advice from instructors and

peers

- develop transferable skills in web authoring and dissemination

The mid-project residential allowed students from different institutions to

meet face-to-face and to reflect on the progress of their group project,

receiving further feedback from teachers and peers. After the shift to

individual projects, the focus of this second residential moved to short

presentations on ongoing progress and challenges, and on the provision of

“feed forward” advice, helping the students to

plan the next steps in their research [

Hattie and Timperley 2007]. For both

group and individual projects, the second residential had the aim of increasing

the opportunities for cohort-building and collegiality among students and

teachers. It also helped to reinforce important employability skills, such as

communication (through presentations on the progress of their project),

critical thinking (by providing “feed forward” on other students’ work)

and problem solving (by sharing suggestions for development with the other

students). Finally, it provided additional opportunities for reflection and

evaluation.

Final presentation

The concluding learning event took place in late April and consisted of

presentations on the group (or individual) projects, discussions on the

projects and an extended feedback session where students expressed their views

on the entire AHDA programme. Sample group projects included mapping medieval

miracles, visualising Early Modern printing networks and building a survey and

database of favourite songs. Individual projects included performing text

analysis on mailing lists and forums, classifying music reviews, visualising

the social networks behind a museum collection, analysing the language of

newspaper articles and of official reports, and building a language corpus.

In the student presentations and discussion, emphasis was placed on process and

reflection, rather than on notions of “success” and “completion.”

Reconnecting to the threshold concepts session at the Winter School, students

were asked to reflect on their research journey, highlighting both milestones

and difficulties. The importance of careful project planning, of documenting

each step of the research process, and of a clear division of tasks within a

team were among the most frequent items to emerge from this reflection phase.

Students were also encouraged to consider the applicability of what they had

learned within their doctoral research and their envisaged future employment

opportunities. Several students, for example, declared the intention to include

their AHDA project as part of seminar presentations, articles and

dissertations, or to further their participation in the digital humanities

community through, for example, further involvement in DH initiatives such as

summer schools or DH seminars and centres in their home institutions.

The AHDA feedback sessions provided the team with essential information to

develop and adjust the programme over the years in order to better understand

the training needs of the students and respond to them. For example, the shift

from group to individual projects was motivated by consistent student feedback,

which highlighted the shortcomings of the group approach. Collaboration is a

central tenet of digital humanities, which is often manifested in

multi-disciplinary project teams and programmes. However, the constraints of

the AHDA programme made effective groupwork difficult. Students were based in

different institutions, often separated by significant geographical distances.

Moreover, they were often at different points in their doctoral student

journeys, ranging from first year to thesis submission. Hence, the other

demands on their time varied considerably. Finally, they had different levels

of commitment to the projects, especially where the fit with their disciplinary

background was poorer, and different degrees of participation in the digital

humanities community.

In order to recognise this diversity within the student cohort, the AHDA team

agreed therefore to move to individual projects, refocusing the group work

objective through the “feed forward” and feedback sessions in the

mid-project and final workshops. The team were impressed by the students’

development of informal support networks, for example through a WhatsApp group,

and their engagement in independent exchanges of expertise, resources and

advice. The vast majority of the goals of the previous group projects were

therefore fulfilled through a self-determined asynchronous contact

strategy.

Conclusion: Evaluating the DEAR Model in AHDA

This article has used the CHASE AHDA programme as a case study to consider how DH

training might be embedded within a student’s broader learning journey. We have

analysed the roles of self-determined learning within DH communities of practice, and

defined digital humanities pedagogy in the context of postgraduate researcher

training. Based on this critical framework, we have introduced the DEAR model for DH

learning and teaching, based on four abstracted principles that can be adapted to

account for locally informed pedagogical practice: Diversity; Employability;

Application; and Reflection. Finally, we have evaluated how we have instantiated the

DEAR model into the CHASE AHDA training programme. This conclusion provides a set of

reflections upon the extent to which DEAR has been successfully implemented in our

programme, and recommends key priorities for those looking to adopt it in their own

pedagogical practices. In doing so, it demonstrates the potential for DEAR to act as

an adaptable framework upon which to shape local multidisciplinary training in

digital humanities.

Diversity

The AHDA programme has certainly embraced the diversity of its candidates,

originally in attempting to address the disciplinary interests through historical

and literary texts, social media, social and economic data and visual and aural

media. Although this may reflect the disciplinary demographics of postgraduate

research in DTPs such as CHASE, it proved difficult to anticipate each year, and

therefore more challenging to cover with our teaching staff.

In terms of diversity in skills and competencies, AHDA has been able to establish

an entry-level approach, which has clearly benefited the majority of postgraduate

researchers in being accessible. This was, however, more problematic for students

working on group projects. In these cases, students with pre-existing knowledge

and higher proficiency in certain methods or techniques were more likely to adopt

technical roles within their groups. This limited the opportunities for other

members to develop comparable skills.

Diversity has much deeper historical, social and political implications. Digital

Humanities as a community of practice may be inclusive in aims, but clearly can do

more to decolonise its curriculum, as shown through the work of groups such as

Postcolonial DH and Global Outlook::Digital Humanities.

[8] Possible avenues include addressing the gaps in the digital archives,

using digital methods to represent marginalised voices, embracing plurality and

using the digital to question dominant narratives [

Risam 2018]. The

CHASE DTP overall is addressing diversity issues through, for example, the BAME

Masterclass series

[9], the Feminist Duration

[10] lecture series, the CHASE Feminist Network

[11] and public lectures such as Decolonising the Nuclear.

[12] A specifically feminist approach to Digital Humanities was introduced with

the 2020 FACT///.coding workshop series, which partnered with Women Who Code

London and the Reanimating Data Project.

[13]

Writing this in an ongoing pandemic, the question of remote attendance is at the

forefront of everyone’s mind, but virtual or mixed seminars are a possibility for

widening participation regardless of wider issues. They offer the opportunity to

support diverse student needs, such as those who have personal or professional

commitments that prevent them from taking part in residential programmes. This

approach would have to be combined with a reevaluation of the programme’s goals

and structure.

Employability

Many candidates on the AHDA programme were motivated by their own projects, i.e.

the PhD itself. The initial focus on group projects was intended to reflect the

collaborative nature of work in digital humanities, but this was not limited to

preparedness for an academic career. The involvement of key partners from the UK

GLAM sector was both a DTP strategic commitment, but also in recognition of the

various career trajectories of doctoral candidates.

Where engagement with employability has been most successful is undoubtedly when

representatives of the GLAM sector and project managers have been involved. These

contributors have repeatedly highlighted the importance of institutional

responsibilities, such as risk management, openness and scalability. Although

candidates could use the AHDA experience as evidence of working with institutions

beyond their immediate academic community, our programme did not focus on

CV-building itself. We have also yet to measure the impact of AHDA on

employability longer term. This would require a survey of the AHDA alumni to see

if the training helped them in their careers, where opportunities in the academic

community are still discipline-oriented. This in turn is heavily dependent on

structural factors, such as the short-term funding provided by the DTP.

Employability, therefore, is not the sole responsibility of this training, but

needs to be part of broader initiatives in the UK addressing mentoring, skills and

career diversity. One way forward may be the public scholarship model proposed by

Cassuto and Weisbuch (2021), which involves

academic knowledge and digital literacies, but also the professional attributes

that are frequently deployed - but often implicit - in the GLAM sector [

Rogers 2020]. The question of employability is an ongoing debate in

DH [

Romanova et al. 2020], for which programmes such as AHDA provide

important context.

Application

The heutagogical ethos of the AHDA programme meant that students needed to take

individual responsibility for the design, execution and evaluation of a project.

In group projects, although the first process involved investment from most group

members, the remaining processes depended heavily on a group’s dynamic and its

diversity.

Consistent motivation and evidencing of learning through design, execution and

evaluation can be better defined and observed through individual projects. Their

final stage is clearly complemented by an anonymous feed-forward approach, which

allows for peer-learning in the absence of a team-based approach.

Application is therefore observed in two ways. The first is in furthering a

student’s PhD research, the second is in making a wider contribution to knowledge,

for example through partnerships with cultural heritage organisations, such as the

British Library, or broadcast media. This is broadly in line with DTP support for

partnerships and placements with CHASE partner institutions.

[14] Ultimately, this involves a movement from what both Nowviskie and Warwick

describe as the unhelpful construct of “hack” versus “yack,” and towards

a praxis-based model of digital humanities in theory and practice [

Nowviskie 2016]

[

Warwick 2016].

Reflection

A reflective approach to learning in the AHDA programme has been key to enabling

the three other core elements of the DEAR model. A recognition of the challenges

of the learning curve at the outset, and the need to effectively self-assess

current skills and knowledge, has been crucial for addressing individual

motivations and outcomes for both the project and for learning itself. In its most

recent iteration, AHDA candidates’ mid-project and final presentations clearly

demonstrated the technical skills acquired and extended abstract thinking [

Biggs and Collis 1982]. Specifically, the projects displayed the conceptual

alignment of the ontological, methodological and epistemological dimensions of a

research project; key characteristics of doctoral candidates [

Berman and Smyth 2013].

Within the DEAR model, such reflection should take into account the other

components of diversity, employability and application as encompassed within the

students’ own learning journey. For example, the AHDA programme’s final reflective

session is delivered as a group, which allows the diverse perspectives of

attendees to feed in, while students are also tasked with addressing the

development and learning outcomes of their project work, thus linking their

reflection back to the application of digital humanities theory in practice. The

iterative approach to reflection adopted in our programme (feed-forward and

feedback) for students’ presentations also addressed the ways in which individuals

identify their next steps, both for development of their own skills set and

realisation of their project(s). These are fundamental aspects of professional

development and employability generally, relating back to the RDF sub-domains B3

and C2 (see

Figure 3).

Recommendations for Practice

This article has conceptualised and applied the DEAR model within the context of

the UK, demonstrating its success in developing a community of practice conducive

to heutagogical learning within an advanced research training programme. However,

the model has applicability for other contexts where a highly reflective,

self-directed style of learning is suited locally to student needs, including

doctoral training programmes internationally. The DEAR approach allows students

the time and space to situate digital humanities within their own broader research

skills development. As such, we see this as complementary to existing summer and

winter schools, which are more focused upon skills development over a compressed

time frame. Although we have cited examples of the projects that participants in

AHDA have undertaken over the years, this study does not advocate adopting a

predefined programme structure. It is the core elements of the DEAR model that are

crucial to its success, such as providing time and space within the programme for

the heutagogical aspects to be prioritised. Programme design should build out from

these core principles, rather than inserting them once a programme is confirmed.

For this reason, while team-taught models of DH training, including AHDA, may well

use reflection, each of the instructors can benefit from building it in as an

explicit value at the design stage.

As a result of running AHDA for several years, we recommend that those

implementing the DEAR model pay particular attention to the following points:

- Focus on participant projects and individual motivations, in order to

scaffold learning and increase engagement with reflective components of the

programme. This could be achieved through small group presentations about

individual learning aims and, resources allowing, alternative pathways through

the programme.

- Encourage peer support for the learning around the project, rather than the

execution of the project, using group feed-forward and feedback opportunities.

For example, students can be encouraged to adopt communication platforms that

best suit them, such as WhatsApp, which create a self-moderated back channel

that facilitates heutagogical learning outcomes.

- Ensure diversity of voices among trainers and support students in developing

core knowledge around the nature of data and project management. One approach

could be to involve individuals with expertise in project management and

interdisciplinary collaboration, such as library, Alt-Ac and industry

professionals in roles allied to digital humanities research and

infrastructure.

- Aim for inclusivity by providing recordings of workshops and preparatory

reading materials and exercises. Organisers may want to use a project blog for

public outputs or draw on existing local technical resources, such as a virtual

learning environment (VLE), where materials cannot be made public. Online

learning may also lower financial overheads, but may come with a potential

trade-off in cohort development that comes with in-person learning.

- The DEAR principles encourage trainers to develop learning environments that

support active learning. This might require additional time commitment within

the programme; if a course requires six hours of taught sessions, then an

additional hour would allow for reflection on learning or application, for

instance.

It should be considered that our implementation of the DEAR model was a

non-credit-bearing programme, and relied on students and staff meeting several

times over a period of four months. Residential programmes carry significant

financial overheads, but in our case CHASE invested extensively in AHDA through

the Training and Development fund, which may not be true of all programmes. One

consideration for instructors is whether the programme is credit-bearing, a core

requirement or extracurricular, which has implications for the availability of

financial and administrative support. Scalability is also an issue, as we would

argue that such an approach inevitably limits the number of participants. As

organisers, we felt that a maximum of twenty to twenty-five students allowed for

effective delivery of the programme aims and objectives.

If the resources for delivering a full training programme are unavailable, the

DEAR model has value as a diagnostic, self-assessment tool in terms of learning

design, which can be deployed for instructors who might be building separate

course modules in a short programme or by postgraduate researchers and PhD

students who need to scaffold their own self-determined learning in DH.

Furthermore, it has potential to become a modular, adaptable framework whereby the

four components are remixed to fit local learning priorities. In this sense it

operates at both the level of the individual and the higher education

institution.

Taking into account our findings, we argue that the DEAR model has great value for

trainers working in a context where digital humanities skills are required.

However to date the DEAR model has only been implemented within CHASE AHDA. We

encourage other digital humanities instructors to adopt and adapt the DEAR model

to their own educational contexts in order to test its application as a means of

framing learning and teaching design within diverse digital humanities

communities.

Works Cited

Berman 2013 Berman, J. (2013) “Utility of a conceptual framework within doctoral study: A researcher’s

reflections,”

Issues in Educational Research, 23(1), pp.1- 18.

Berman and Smyth 2013 Berman, J. and Smyth, R.

(2013) “Conceptual frameworks in the doctoral research process: a

pedagogical model,”

Innovations in Education and Teaching International,

52(2), pp. 125–136. doi:

10.1080/14703297.2013.809011.

Biggs and Collis 1982 Biggs, J.B. & Collis, K.F.

1982, Evaluating the quality of learning: the SOLO taxonomy

(structure of the observed learning outcome). New York: Academic

Press.

Blaschke 2013 Blaschke, L. M. (2013) “E-Learning and Self-Determined Learning Skills,” in Hase, S.

and Kenyon, C. (eds) Self-Determined Learning: Heutagogy in

Action. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 55–67.

Bonds 2014 Bonds, E. L. (2014) “Listening in on the Conversations: An Overview of Digital Humanities

Pedagogy,”

CEA Critic, 76(2, pp. 147-157). Available at:

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/550519#b43 (Accessed: 9 October 2020).

CHASE DTP 2020 CHASE DTP (2020)

CHASE Doctoral Training Partnership CHASE DTP. Falmer: University of

Sussex. Available at:

https://www.chase.ac.uk (Accessed: 28 July 2020).

Cassuto and Weisbuch 2021 Cassuto, L. and Weisbuch,

R. (2021) The New PhD: How to Build a Better Graduate

Education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cordell 2016 Cordell, R. (2016) “How Not to Teach Digital Humanities,” in Gold, M. K. and Klein, L. F.

(eds)

Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis and

London: University of Minnesota Press. Available at:

http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/87 (Accessed: 9 October

2020).

Elliot et al. 2020 Elliot, D.L., Bengsten, S.S.E.,

Guccione, K. & Kobayashi, S. 2020, The Hidden Curriculum in

Doctoral Education. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ensslin and Slocombe 2012 Ensslin, A. and Slocombe,

W. (2012) “Training humanities doctoral students in collaborative

and digital multimedia,”

Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 11(1–2), pp.

140–156. doi:

10.1177/1474022211428897 (Accessed: 9 October 2020).

Gooding 2020 Gooding, P. (2020) “The Library in Digital Humanities: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Digital

Materials,” in Dunn, S. and Schuster, K. (eds) Routledge Handbook on Research Methods in Digital Humanities. London:

Routledge.

Harrison et al. 2016 Harrison, J., Smith, D. P. and

Kinton, C. (2016) “New institutional geographies of higher

education: The rise of transregional university alliances,”

Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(5),

pp. 910–936. doi:

10.1177/0308518X15619175.

Hase and Kenyon 2013 Hase, S. and Kenyon, C. (eds)

(2013) Self-Determined Learning: Heutagogy in Action.

London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hattie and Timperley 2007 Hattie, J. and Timperley, H.

(2007) “The Power of Feedback,”

Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81–112. doi:

10.3102/003465430298487.

Hinrichsen and Coombs 2013 Hinrichsen, J. and

Coombs, A. (2013) “The Five Resources of Critical Digital

Literacy: A Framework for Curriculum Integration,”

Research in Learning Technology 21, pp. 1-16. Available

at:

https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21.21334 (Accessed 9 October 2020).

Kiley and Wisker 2009 Kiley, M. and Wisker, G. (2009)

“Threshold concepts in research education and evidence of

threshold crossing,”

Higher Education Research & Development, 28(4), pp.

431–441. doi:

10.1080/07294360903067930.

Klein 1990 Klein, J. T. (1990) Interdisciplinarity: History, Theory, and Practice. Detroit: Wayne State

University Press.

Klein 2014 Klein, J. T. (2014)

Interdisciplining Digital Humanities: Boundary Work in an Emerging Field.

Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dh.12869322.0001.001 (Accessed: 9 October

2020).

Knowles 1970 Knowles M.S. (1970) The Modern Practice of Adult Education: Andragogy versus Pedagogy. New

York: Associated Press.

Mahony 2014 Mahony, S. et al. (2014) “Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Integrative Learning and New Ways of

Thinking About Studying the Humanities,” in Mills, C., Pidd, M., and

Williams, J. (eds)

Proceedings of the Digital Humanities

Congress 2014. Sheffield: Digital Humanities Institute (Studies in the

Digital Humanities). Available at:

https://www.dhi.ac.uk/openbook/chapter/dhc2014-mahony (Accessed: 25

September 2020).

Nerad 2007 Nerad, M. (2007). “Doctoral Education in the USA,” in Powell, S. and Green, H. (eds.) The Doctorate Worldwide. Maidenhead: The Open University

Press, pp. 133-140.

Powell and Green 2007 Green, H. and Powell, S. (2007)

“Doctoral Education in the UK,” in Powell, S. and

Green, S. (eds) The Doctorate Worldwide. Maidenhead: The

Open University Press, pp. 88–102.

Praxis Network n.d. The Praxis Network (n.d.). “Home · The Praxis Network.”

http://praxis-network.org/ (Accessed:

8 September 2021).

Risam 2018 Risam, R. (2018) “Decolonizing the Digital Humanities in Theory and Practice,” in Sayers, J.

(ed.)

The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital

Humanities. 1st edn. New York : Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group,

2018.: Routledge, pp. 78–86. doi:

10.4324/9781315730479-8.

Rogers 2020 Rogers, K.L. (2020) Putting the Humanities PhD to Work: Thriving in and Beyond the Classroom.

London: Duke University Press.

Romanova et al. 2020 Romanova, N., Ciula, A.,

Smithies, J., Jakeman, N., Murphy, Ó., Tupman, C., Winters, J. Edmond, J., Doran, M.,

Gooding, P., Hughes, L., Murrieta-Flores, P., and Tonra, J. “Capacity Enhancement in Digital humanities in the UK and Ireland: Training and

Beyond.”