As technological tools have developed over the last several decades, humanities

scholars have explored the opportunities computing technology makes available for

conducting and enhancing their research. Scholars have developed techniques such as

using software to mine texts and creating data visualizations such as maps, charts,

and graphics. Further, they have developed new software products to aid in their

research. These techniques allow scholars to grapple new kinds of qualitative and

quantitative research questions, as well as to work with data and text at scale.

Similarly, archivists and librarians have developed an extensive literature and tool

set to collect, accession, make accessible, and preserve a wide variety of digital

content for their collections. Many of these skills and techniques overlap with

those of DH practitioners; for example, digitizing a text document and performing

optical character recognition to generate a searchable transcript could be a key

step in both a DH scholar's research and an archivist's making a historic pamphlet

accessible for researchers. Furthermore, texts and DH projects generated by the work

of DH scholars might be worth accessioning and preserving as part of their

collections; steps in the archival workflow might have to be adjusted to accommodate

data sets, websites, applications, visualizations, and other products that result

from DH scholars' work.

The present study will investigate the perceptions of information professionals (IPs)

about their role in the work of DH scholars, as well as the perceptions of DH

scholars on the role of IPs in their research. While other scholarly literature has

considered collaborations between these groups via surveys or interviews with small

project teams (e.g.,

Keener 2015,

Poremski 2017), the present study will provide a

large-scale analysis of collaborations using survey responses from more than 500

scholars, librarians, and archivists. The survey questions were based upon findings

in a literature review focusing on DH labor, best practices, and case studies, and

were designed to identify trends across both groups. I wanted to determine the

extent to which these groups collaborate with one another on project teams.

Questions sought to ascertain how these collaborations unfold and who initiates

them; whether IPs have begun to adjust and adapt their work to support specific DH

projects, or to make their content more appealing and easy for potential future DH

projects; and what administrative hurdles are faced during the collaboration. After

working together, how do IPs and DH scholars view the success of the collaboration,

and do they intend to collaborate in future? What do these responses tell us about

how best to support all members of these collaborations?

Survey Results

Participants

Of the 508 survey responses, nearly 48% identified themselves as an

archivist, librarian, or a graduate student in either of these areas. Nearly

34% identified themselves as a faculty member (20.35%) or graduate student

(13.31%) in a subject area outside of library or archives. Of the remaining

respondents, approximately 10% self-identified academic researchers,

administrators, or IT professionals. For the purposes of this article, I

will distinguish between two groups: information professionals (IPs), which

consist of librarians, archivists, and graduate students in those two

disciplines (48% of the total); and other digital humanities scholars (DHs),

which consist of subject faculty, students in subject disciplines,

alt-academic scholars, administrators, and others (52%).

Studying and comparing the responses of information professionals to those of

other types of digital humanities scholars does highlight, and perhaps

reify, a binary between those two groups. As the above literature review

demonstrates, information professionals conduct digital humanities research

alone and in collaboration with other scholars, and casting them as distinct

from other scholars poses the risk of painting them as less qualified

researchers, or erasing their work from discussions of digital humanities as

a field. However, as Posner argues and as the survey results will show,

information professionals face different workloads than other DH scholars

often do, especially those scholars for whom teaching and research is a

primary responsibility [

Posner 2013]. Further, administrative

structures and funding requirements, as well as expectations of a “service

orientation”, work differently in library and archives departments

than in academic departments (or, indeed, in information technology

departments or digital humanities centers). Grouping and comparing responses

as I do below allows me to explore how these realities affect the experiences

of the collaborative partners.

I also inquired about the subject specialties of the faculty and graduate

students responding to the survey. 43.25% of respondents said that English,

literature, foreign language literature, writing, or affiliated disciplines

were their area of expertise. 17.85% indicated history, while an additional

3.78% specified Medieval history or studies. Remaining respondents mentioned

a variety of other disciplines, including anthropology, art and art history,

media studies, and, indeed, digital humanities. The majority of respondents

(77.24%) reported working in a college or university setting, with the next

largest group employed at museum or arts organizations (7.09%). 24.66% of

the graduate student respondents reported that they were enrolled in a

digital humanities track or major. In this survey, I did not ask respondents

whether their institution had a standalone Digital Humanities Center; this

would be an interesting avenue for further research.

The vast majority of respondents worked on at least one digital humanities

project: 18.45% had worked on one project, and 73.02% had worked on more

than one. I instructed respondents who had worked on multiple projects to

consider their most recent project when answering the survey questions.

One line of inquiry not included in this survey pertains to the employment

status of respondents: or whether they held a faculty, administrative or

staff role; if they were faculty, whether they were full-time or adjunct;

whether they were tenure-track or tenured; or if librarians or archivists,

whether they held faculty status or staff status. Further research on how

employment status affects collaborations, funding, and administrative

support could be very fruitful.

Nature of Digital Humanities Deliverables

I asked all respondents to describe the DH projects they had worked on,

asking them to mention deliverables and which members of the team

contributed to which aspects of the project. I chose not to provide a

definition for "digital humanities project" in order to allow respondents to

include anything that met with their own definition of the idea. Indeed, one

respondent wrote that they were not sure whether to include their project

because “[a]rguably, this isn't digital humanities, but

the phrase has been stretched so far that some people would include it

in their definition – [I]'m not sure what yours is.”

Many respondents described multiple projects in their response to this

free-text question, or included a number of digital humanities workflows or

outputs that dealt with a particular collection or theme. I collected 201

responses to this question. I analyzed the responses and flagged recurring

features that were listed, such as websites, digitization projects, and

application development; this analysis generated 546 features (for the

purposes of this article, I will refer to these features as

data

points). For this particular question, I calculated percentages

based on the number of responses; because most responses mentioned projects

with several features, and some responses even mentioned multiple projects,

I wanted to show how many individual practitioners mentioned particular

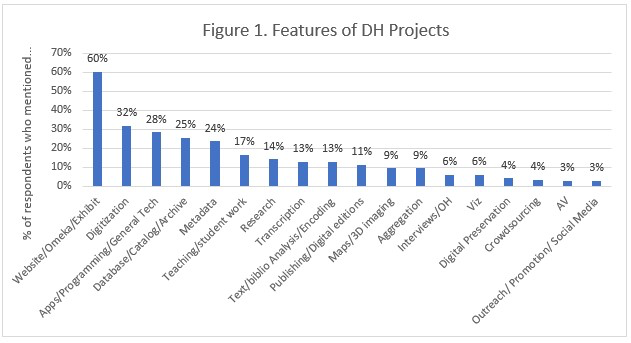

features in their answers. The results of this question can be seen in

Figure 1.

For these respondents, then, a web component is key, either for delivering

the results of their analysis or as the deliverable itself. Approximately

60% of respondents mentioned a website, Omeka gallery, or web exhibit as an

outcome of their projects. Approximately 32% mentioned digitization of print

or analog materials. Approximately 28% mentioned programming, creation of

applications, use of Scalar, or other technical work. Approximately 25%

mentioned creation of a database, catalog, or searchable archive, and

approximately 24% of respondents mentioned metadata work. Interestingly,

some hallmarks of digital humanities projects, including maps, data

visualizations, and textual analysis, were mentioned by fewer than 15% of

respondents each.

Indeed, because the framing of the question focused primarily on

deliverables, few respondents went into depth discussing their research

methodology, subject selection, or critical approach. This is a blind spot

in the research design: perhaps because of my information-professional

approach, I focused on the research products rather than the lines of

scholarly inquiry advanced by these collaborations. In part, this serves to

hide the intellectual contributions of all respondents, particularly

information professionals, who may have fewer fora to showcase their

research output [

Posner 2013]. Future research might inquire

and analyze the scholarly dialogue between collaborators in IP and DH

partnerships.

Initiating the project: Beginning the Collaboration

Next, I wanted to identify who initiated collaborative projects: did subject

specialists reach out to information professionals, or vice versa? How did

these collaborations begin? When I asked information professionals about

their collaborations with academic colleagues, 61.93% of the total responses

(197) mentioned collaboration with faculty or professional colleagues from

their own institution; 11.17% of responses mentioned that they worked with

graduate students from their own institution; 16.24% reported working with

faculty from other institutions; and 1.52% described working with graduate

students from another institution. 9.14% of respondents mentioned that they

worked on their project(s) alone.

[2] Again, these respondents were removed from the remainder

of the survey at this juncture.

| Information professionals collaborated with… |

Percentage of Respondents |

n= |

| Faculty/ Professional colleagues, same

institution |

66.03% |

103 |

| Faculty/ Professional colleagues from another

institution |

12.82% |

20 |

| Students from my institution |

10.90% |

17 |

| Alone |

9.62% |

15 |

| Students from another institution |

0.64% |

1 |

| Total |

100.00% |

156 |

Table 1.

Table 1. IP Collaborations

When I asked academic colleagues about their work on projects with library

and archives professionals, their responses were as follows. Out of 231

respondents, 37.23% said they worked with both archivists and librarians.

20.35% reported that they worked with librarians; 11.26% reported that they

worked with archivists; and 7.36% said they worked with information

professionals but were not sure whether they were librarians or archivists.

23.81% reported that they worked on their projects alone. Of course, as this

survey was clearly described as being designed to study collaborative

projects, it is no surprise that those who took the survey had collaboration

experience. (Again, at this juncture of the survey I removed any additional

respondents who reported working alone on their projects.)

| DH Scholars collaborated with… |

Percentage of respondents |

n= |

| Colleagues in both areas |

37.23% |

86 |

| Librarians |

20.35% |

47 |

| Alone |

23.81% |

55 |

| Archivists |

11.26% |

26 |

| Yes, but not sure which |

7.36% |

17 |

| Total |

100.01% |

231 |

Table 2.

Table 2. DH Collaboations

Next, I asked the DH scholars and the information professionals whether they

initiated the project themselves, or were invited to join by a colleague.

The standout finding here is that almost 78% of the time, faculty

respondents said that the project was their idea, and they reached out to

their information professional colleagues to join them. For the archivists

and librarians who responded, over 50% of the responses indicated

that faculty colleagues initiated the project (51.56% of responses for

archivists and 53.70% for librarians). For the archivists and librarians,

responses ranged between 19 and 25% for initiating the project on their own

or for coming up with the project in tandem with their colleague. This

finding shows that for these respondents, academic researchers are

frequently initiating collaborations with information professionals for some

portion of their project.

This response is underscored by the next set of questions, displayed

in Table 3. I asked anyone who responded that

the project had been initiated by a colleague how they came to be involved.

First, approximately 72% of the respondents to this question were

information professionals, which confirms the findings in the previous

question. I broke the responses down: for information

professionals, approximately 27% were simply asked to join by colleagues;

approximately 18% had a skill necessary to complete the project;

approximately 18% have jobs that explicitly include DH projects in their

scope; approximately 9% were part of a staff or team that were assigned the

project; approximately 9% applied to a job opening that included work on

that project; and approximately 7% invited themselves onto the

team/volunteered to participate. 13% had another response.

| Method |

Information Professionals (n=44) |

DH Scholars (n=17) |

| Part of staff/team that was assigned specific

project |

8.9% (n=4) |

15.8% (n=3) |

| Had Necessary Skills/In a role that is required to be

looped in |

17.8% (n=8) |

21.1% (n=4) |

| Other |

13.3% (n=6) |

10.5% (n=2) |

| Invited Myself |

6.7% (n=3) |

21.1% (n=4) |

| Was Asked |

26.7% (n=12) |

15.8% (n=3) |

| Applied for Job Opening/Internship |

8.9% (n=4) |

10.5% (n=2) |

| Job Explicitly Includes DH |

17.8% (n=8) |

5.3% (n-=1) |

|

|

|

Table 3.

Table 3. Ways Collaborators Joined Projects They Did Not

Initiate

In contrast, when I broke down the responses for academic and professional

colleagues, the responses were as follows: approximately 16% were simply

asked to join by colleagues; approximately 21% had a skill necessary to

complete the project; approximately 5% have jobs that explicitly include DH

projects in their scope; approximately 16% were part of a staff or team that

were assigned the project; approximately 11% applied to a job opening that

included work on that project; and approximately 21% invited themselves onto

the team/volunteered to participate. 11% had another response.

Information professionals are still much more likely to be asked to join a

project than subject faculty and other academic colleagues. Academic

colleagues were much more likely to invite themselves to join a project of

interest to them. Both IPs and scholars were roughly equally likely to be

asked to join because of a skill they possessed. IPs were much more likely

to have a job that explicitly includes DH work, but academic colleagues were

much more likely to be part of a team assigned to a DH project. These

responses demonstrate that scholarly researchers outside of the library have

more opportunities and flexibility to take on DH projects if they are

interested in doing so. Information professionals may be more likely to be

constrained by their role, or limited by time and resources, as we will see

later in this study; this may prevent them from being the primary motivator

in establishing DH projects. However, another factor to consider is

cultural; the longstanding perception of librarians and archivists as

service-providers may be entrenched enough that scholars are more likely to

draw on IP’s expertise than the other way around. Further research could

examine constraints on when information professionals initiate projects.

Successes and failures

Both DH scholars and information professionals were asked to reflect upon

their interactions with colleagues, and asked to suggest what could be done

to improve similar (or future) collaborations. 57.89% of the DH scholars

responded that the collaboration was successful, with another 31.58%

responding that they had mixed results. Only 3 responses (2.63%) were a

clear “no” (the remainder were coded as N/A, other, or that the project

was still ongoing). Those scholars who felt they had a mixed experience most

commonly mentioned that they wished the library/archives staff had more time

or resources to share. Several also mentioned that they would have liked

more clarity about project planning and timelines; more training so they

could do more of the work on their own; or more of a mutual understanding

around key project terms like metadata,

preservation, and sustainability.

The information professionals’ assessment was a bit more complex. 82

information professionals answered this question. Of these, 28.05% said it

was a successful collaboration; 8.7% said it was not; 58.54% said it was a

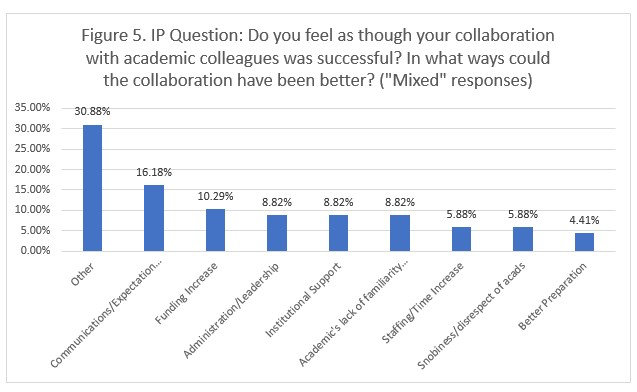

mix; and 3.66% said N/A or other. I then broke the “mixed” responses

into categories, to further analyze their explanations; these responses were

parsed into 68 data points. 16.18% of the data points mentioned issues

around communication, responsiveness, and expectation-setting with their

faculty counterparts. 10.29% mentioned that the project would be more

successful with increased funding. 8.82% mentioned issues around leadership,

coordination, and decisionmaking; 8.82% mentioned the lack of familiarity on

the part of faculty with IT or librarianship/archival work and what would be

possible to accomplish; and another 8.82% mentioned the need for improved

institutional support (aside from funding). For example, one librarian

wrote, “Collaboration with my immediate colleagues

was/is successful, but the way our projects fit into the overall library

structure is still very tricky. [Our digital project has an] unfunded

mandate and this model is not sustainable, in terms of staff time

required. So, it's not that collaboration could be better but the

infrastructure around the collaboration needs to be better.”

Another librarian wrote, “Collaboration with faculty was

good. Getting buy in from library admin is harder.”

From these responses, information professionals seem to be frequently turned

to for support and labor, and they would like to be able to do these digital

humanities projects. However, they may not have the time, resources, or

support to do so. Further, many respondents mentioned that faculty

colleagues had different expectations than they did around what was possible

via their collaboration: how much time it would take, how responsive each

party would need to be, and what kind of IT or library work was feasible and

what was not. Further research could highlight the hurdles, especially

administratively, that prevent information professionals from working on

digital humanities projects.

Interestingly, 5.88% also mentioned that they felt some snobbery or

dismissiveness on the part of faculty against their information professional

counterparts. One archivist said, “It was hard for

academic colleagues to acknowledge the fact that I am myself also

faculty and also have research interests to pursue…. They didn't

understand why I was driving the project, and thought it needed to come

out of a pet question or topic under study by a ‘serious’ scholar.

I was studying user response to data visualizations. And I got an

awesome digital humanities project out of it.” It is important to

note, however, how few responses mentioned this kind of tension.

I also asked several questions pertaining to issues around resource

allocation, which provide a preliminary snapshot into the funding associated

with these respondents’ DH projects. First, all respondents were asked, in a

free-text question, “How was the project funded?”

Each respondent could list as many responses as they desired; phrases were

coded and collected to yield 272 data points. Of these, 36.76% of responses

mentioned receiving no additional funding at all to complete the project;

the project was funded only out of regular salary or department funds. A

similar percentage, 37.78%, of responses included a mention of funding by

external or governmental grants (respondents who identified as DHers were

more likely to mention that they had external funding: 41.28% of DHers

mentioned external or governmental grants in their responses, whereas only

32% of IPs did). Additional funding for these projects came in the form of

internal (departmental or institutional) grants. Responses across these

categories were consistent between DH and IP respondents, aside from the

difference in those reporting external grant funding.

Next, I asked all respondents, “What extra resources (eg

staff, time, equipment), if any, did completion of the project

require?” This, too, was a free-text question, and answers were

parsed and coded. Out of a total of 356 responses, the most frequent

responses were staff time (specifically existing staff time reallocated from

other projects and responsibilities) at 35.92%; acquisition of equipment or

software at 24.14%; and additional staff, volunteer or students hired, at

18.10%. Response rates for each of these categories were similar between DH

and IP respondents.

Lastly, due to my interest in institutional support for information

professionals participating in DH work, I asked only the IP respondents to

“Please describe any support, interest, or

roadblocks you faced from supervisors while taking on this

project.” Out of 76 respondents, 57.89% reported that they

received support from their supervisor. Respondents were also permitted to

add a free-text explanation to this answer; the most popular issues they

reported supervisors mentioning were concerns around the time it would take

to complete the project (15.79%); IT support (9.21%); issues around funding

(9.21%); and issues around copyright (3.95%).

These results provide some preliminary context for the key issues

collaborative partners face in their work in DH. Many projects were

supported by external grant funding. A lot of the projects were completed

using existing staff and staff time, rather than via an injection of

additional resources or staff. Many projects were not awarded any additional

funding at all. A slim majority of information professionals reported

support from supervisors, but supervisors mentioned concerns about the

investment of time and resources required to participate in these DH

projects. As a practicing information professional, these results suggest to

me that while there is a lot of interest in this work among scholars,

information professionals, and supervisors, resources may be limited to

complete it, and for information professionals in particular, projects of

this type that may be added to more established workloads represent a

resource crunch rather than an inducement to build capacity. Further

research is necessary to understand the varied experiences of library

scholars and other researchers, as well as the responses and support

provided by their administrative and institutional contexts.

The role of IPs, according to DHers

Next, I wanted to explore the ways digital humanities scholars outside the

library perceived the role of information professionals in contributing to

their shared projects, and how that might have changed as a result of

working with an information professional. I targeted a series of questions

to the digital humanities scholars about their perceptions.

First, I asked, “Has your understanding of the work of

your archives/library colleagues changed in any way? Please

explain.” There are 69 free text answers to this question. Most

people responded that they learned something new (60.87%), and the majority

of these new things can be characterized as positive. Examples include:

“I have more respect for their skills and

knowledge”; “I have a better understanding of

the different roles of librarians/archivists”; and “I have more ideas about collaborating with them in the

future.” Nearly 57% of the answers in the lessons

learned category pertain to the subject researchres learning more

about what goes into library work. For example, one respondent wrote: “I wasn't aware before of the ‘mismatches’ between

archival metadata (like EAD) versus the kinds of metadata other academic

researchers need for searching and retrieval.” However, not all

the lessons learned were positive: some people (nearly 16%) learned lessons

they described in negative terms, such as that information professionals

“don't have good technical skills” or that

they were not aware of how understaffed the libraries were. In addition,

some responded that they were already well aware of what information

professionals do from having worked with them extensively in the past.

Next, I asked DH scholars to explain whether they felt it was the role of

archivists and librarians to prepare analog materials for use in digital

humanities projects, such as by digitizing text or adding geodata to maps.

Many archivists and archival repositories are seeking ways to make their

collections more visible and usable by seeking to participate in such

digital projects; I was curious to see whether DH scholars expected this

work from IPs. The answers to this question were, again, a mix. 37.35% of

respondents said yes; 10.84% said no; and 38.12% said they were unsure, or

that it wasn’t necessarily in the purview of archivists and librarians.

Some respondents added comments or explanations to their response; I parsed

these into 136 data points for analysis. 8.82% of the responses mentioned

that this work should be done as a collaboration between information

professionals and scholars; and 4.41% mentioned that IPs, on their own,

would not know what should be digitized or prepared for DH projects, and

should rely on scholar-driven research to develop their projects. This kind

of answer points to some interesting contrasts in training and expectations

among IPs and DH scholars. Many information professionals are experienced

with selecting materials to highlight, and many are subject specialists

themselves. Further, library and archival training can help teach IPs to

identify materials that would be of interest to scholars. In fact, within

the last fifteen years, the archival community has focused resources on

processing and showcasing “hidden collections,” those materials that

might not have been yet made visible to users due to resource or time

constraints. From the perspective of IP training, digitizing collections and

making them accessible can be a way to draw the attention of scholars and

develop new projects around their holdings. However, resource constraints

often limit IPs’ ability to do this kind of work.

DH scholars, on the other hand, might have an area of particular interest to

their own scholarship. Their work is project-based and tied to specific

corpora that would support their own research. As one respondent put it, IPs

shouldn’t preemptively digitize materials because “often

they don't know what might be of interest to scholars.” As

another put it, “I don't know how [to] help librarians

know which materials to prioritize, and it would be a shame to invest an

enormous effort into digitizing, collecting, or correlating data that

then never gets used.” However, it

is an expected part of an information professional’s purview to perform

research and investigate what content is most suitable for digitization, if

resources permit.

Next, I asked scholars whether they felt that it was the role of information

professionals to “preserve and make accessible in the

long term digital humanities projects created by scholars like

yourself?” I had 80 responses to this question; 61.25% said yes,

this is within the purview of IPs, 7.5% said no, and 31.25% said not sure or

not necessarily. A number of these respondents provided more detail in their

explanation; I parsed these into 28 data points, and the most popular

answers were as follows. 21.43% of the answers mentioned that IPs should

continue providing access to digital humanities projects like they have

always done with other resources, like books. 21.43% mentioned that

information professionals doing this sort of preservation work preserves the

relationship between a scholar, their work, and their institution; and

14.29% mentioned the idea that libraries have the resources or

infrastructure necessary to do this sort of preservation. 14.29% argued that

information professionals and digital humanities scholars should be having

conversations and what sorts of work should be preserved and why. Overall,

most scholars reported support for the notion that information professionals

should be involved in this work.

To conclude this section, I asked DH scholars, “How can

archivists or librarians help your work in future digital humanities

projects?” Responses varied widely. I parsed the responses into

109 data points, and they break down as follows. Most respondents (24%)

requested help with technical and library skills. 13.76% mentioned an

interest in initiating or improving more collaborations. A number of

respondents asked IPs to “share,”

“collaborate,”

“connect,” and “contribute” (12.84%) to overall projects. 4.59% of the answers

highlighted help with metadata specifically. 4.59% mentioned that time and

funding hurdles can prevent DHers from capitalizing effectively on IPs'

expertise. Other noteworthy themes: some DH scholars noted that IPs are key

for providing access and acting as gatekeepers to particular materials

(2.75%), with another 5.5% asking IPs not to be “obstructive” and to have a better attitude about sharing

resources and listening to the needs of DHers. 2.75% said that IPs need to

improve their own technical skills before they can be helpful. And 12.84%

simply said wanted archivists and librarians to keep positively supporting

their work: IPs should “keep being awesome;” they

should “keep doing exactly what they have been doing,

which is being well-trained, interested colleagues open to new form[s

of] digital scholarship;” and noting that “librarians and archivists are historians' best friends :-)”

The role of IPs, according to IPs

Turning now to the perspective of information professionals on their role in

digital humanities projects, I asked them a series of questions about their

experiences. First, I asked archives and library respondents whether they

felt digital humanities projects were part of their role. The results were

overwhelmingly positive: 55.84% said yes, that these projects were

explicitly part of their role; another 24.68% said they were somewhat or

tangentially related to their role; and another 3.90% said they built

digital humanities projects into their role. Only 14.29% said DH projects

fell outside the scope of their work. These answer demonstrate that

information professionals now expect to do this work as part of the course

of their librarianship.

I then asked information professionals about the ways they might have altered

their workflows to accommodate the needs of DH projects. First, I asked,

“Did your work on the project contribute to any of

the traditional archival life cycle steps, such as Arrangement,

Description, Preservation, or Providing Access? Please explain.

(Examples include digitizing analog text for the project that could

provide increased access, or taking steps to ensure digital preservation

of a website created as part of a DH project.)” I parsed the

results to yield 122 answers. Most respondents highlight ways they provided

all or most of these. Some used the word “digitization” in general, but it's not clear whether they felt

this was associated with access, preservation, or another step that I

highlighted; I classified those responses as other. 34.43% of

the responses mention access; 18.85% mention preservation; 24.59% mention

arrangement/description; 12.30% were classified as other; and

the remainder (9.84%) said No or N/A.

For the next question, I asked information professionals, “Did you change any of your standard archival workflows to

accommodate this project, or in anticipation of future similar projects?

(For example, did you switch to higher quality OCR software to support

text mining? Did you embed geographical metadata into a digitized map to

allow for geodata visualizations?)” First, I broke the 69

responses from information professionals down into yes

(44.93%), no (36.23%), N/A (8.7%), and

other (5.8%). A number of the respondents explained their

answers; I parsed these answers into 108 responses, the most popular answers

of which broke down as follows. 9.82% made changes in the realm of metadata;

7.14% made changes in their work with mapping and geodata; 4.46% made

changes to their digitization workflows; 2.68% changed their staffing to

accommodate the new projects; 1.79% made changes with OCR; 1.79% changed

their data visualization procedures; and 1.79% reported that they didn’t

have standard workflows in place before this project, but the project helped

to implement them.

Finally, I asked information professionals whether they planned to provide

long-term access or preservation for this project. There were 69

respondents. The vast majority (64.38%) said Yes, they plan to ensure

ongoing access or preservation in some form or fashion, with another 12.32%

percent saying that they are still working it out. 15.07% percent said no,

though several of these said it's because their projects were pedagogical in

nature or proofs of concept, so they were not designed to be kept for the

future. 5.48% responded in some other way.

Conclusions

The survey results and analysis provide a number of conclusions and suggestions

for further research. First, it seems clear that collaborations between subject

researchers and information professionals are happening, and happening

frequently. Secondly, while information professionals generally see digital

humanities projects as within their purview, they are not initiating these

collaborations nearly as frequently as their digital humanities scholar

colleagues. Why are the information professionals not initiating as often? This

is an area for further research, but responses in this survey suggest that

information professionals are often so limited in their available staff time and

resources that they will work with a colleague when approached but are not able

to prioritize these projects from within their own departments.

Next, this survey lends support to Rosenblum and Dwyer’s (2016) argument that in

collaborations between subject researchers and information professionals, tasks

do not necessarily break down into expected categories in which the subject

expert is in charge of the academic research questions and interpretation, and

the information professional is in charge of tools, implementation, and support.

Based on my analysis of the projects described here, information professionals

and subject specialists shared many tasks, and sometimes did tasks outside of

what would traditionally have been their expected purview. For example, one

academic researcher wrote, “My archivist colleague

participated in the design of metadata fields, tutorials for appraisal,

finding additional sources of funding. I was responsible for the design and

development of the digital archive, outreach, funding and securing a home

for it.” In many projects, however, archivists and librarians are

serving in a more “support” role, doing project management, digitizing

materials, working on metadata, and learning and teaching new tools or software

products.

This survey revealed intriguing responses regarding the impressions information

professionals and digital humanist researchers had of working with each other.

While, generally speaking, the researchers felt that their projects were

successful and the information professionals were supportive colleagues with

whom they enjoyed working and whose expertise they valued, responses from the

information professionals were more mixed. Many felt that they had difficulty

working collaboratively with researchers, had trouble setting appropriate

expectations and communicating clearly. This may support Schaffner and Erway’s

contention that collaborations might be difficult because many humanities

scholars are very used to working on their own, and may not have much practice

successfully negotiating a collaborative research project [

Schaffner and Erway 2014, 8]. On the other hand, many information

professionals responded that they felt their collaborative work was very

successful, but it would have been improved with more administrative buy-in or

support in the form of staff time, funding, or other resources.

The survey results indicate that these collaborations, on average, tend to be

viewed as successful and mutually beneficial by both parties, especially when

institutional support is available. However, information professionals do report

more difficulties with the collaboration, with resources, and with

administrative buy-in. Institutional conditions must adapt to support more of

these projects, and in particular funnel resources toward archivists and

librarians to do this work and support long-term sustainability of these

projects.