DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly

2019

Volume 13 Number 3

Volume 13 Number 3

Textension: Digitally Augmenting Document Spaces in Analog Texts

Abstract

In this paper, we present a system that automatically adds visualizations and natural language processing applications to analog texts, using any web-based device with a camera. After taking a picture of a particular page or set of pages from a book or uploading an existing image, our system builds an interactive digital object that automatically inserts modular elements in a digital space. Leveraging the findings of previous studies, our framework augments the reading of analog texts with digital tools, making it possible to work with texts in both a digital and analog environment.

INTRODUCTION

Printed books still remain persistent in the workflow of scholars even though

there is a plethora of digital options available that afford great power and

flexibility to the user. Word processors and other applications have been

completely integrated into people’s daily lives and have started to replace pen

and paper as a modality for interacting with the written word; when it comes to

books, the affordances offered by digital platforms such as search and copy are

considered paradigm shifting additions to the act of reading. But, even though

these tools exist, scholars still write on paper and still have books on their

bookshelves. There is a tension that exists between these new digital formats

and our history. We often create digital tools to mimic the affordances of

books, but while they improve steadily, the weight, smell, and sounds of a book

are still unique to bound paper and ink. It is important to note that it is

still not known how these affordances affect cognition, and for literary

scholarship, interpretation. Mehta et al. studied fourteen literary critics and

found that each had idiosyncratic methods of marking up a literary document, but

most importantly, all of them engaged in some form of annotation when working

with poetic texts [Mehta 2017]. Our own domain expert, a modernist

literary critic, confirmed the findings of that study and presented the idea to

us for a system that allows scholars to quickly digitize a document for

augmentation but retain the look and feel of the original.

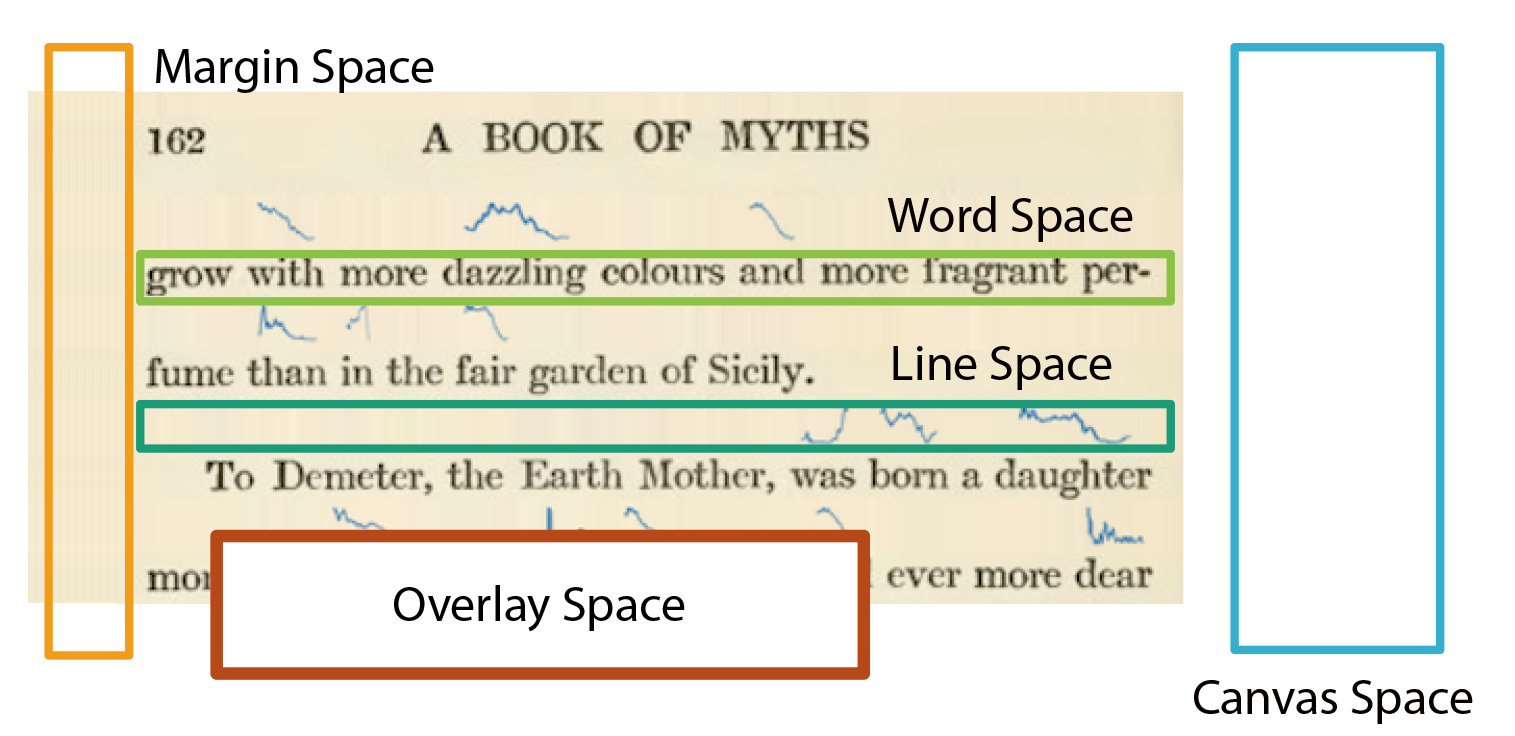

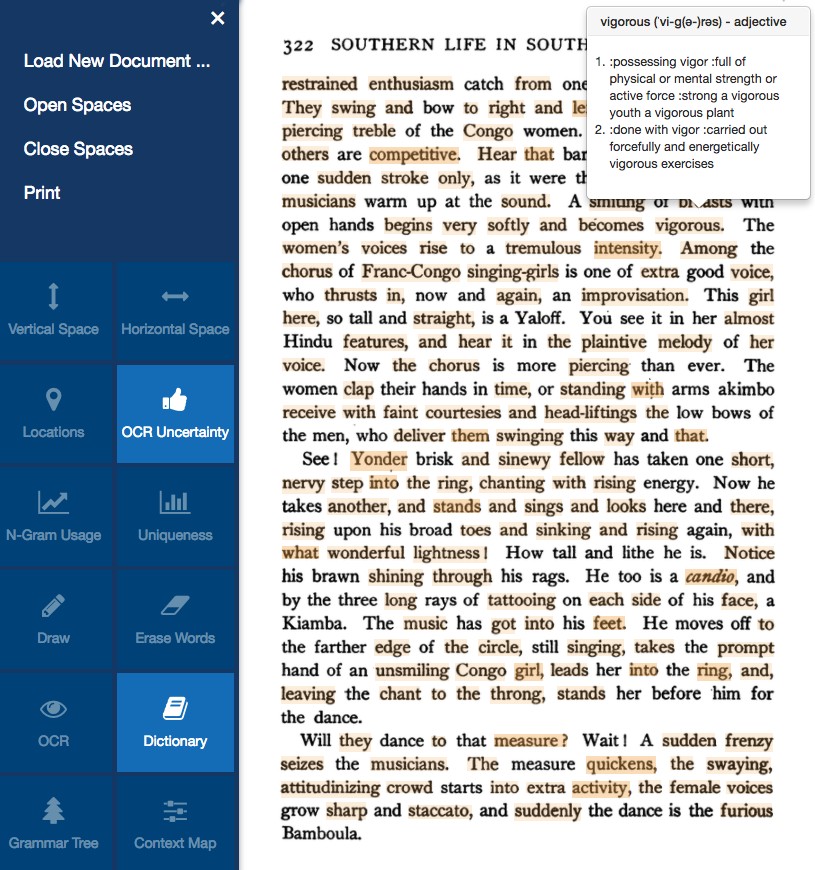

Figure 1.

The five document spaces that can be used for placement of interactive

elements: Word Space, Line Space, Margin Space, Occlusion Space, Canvas

Space. In this image, the line space has been automatically expanded and

sparklines inserted.Beyond the affordances of physical texts, many older texts used for research

often do not have reliable digital versions, and many corpora are still

digitized as images such as Early English Books Online [EEBO 2003]. The solution we offer is a combination of techniques that bring together the

paper and ink history of our past, with the digital affordances of our present.

To demonstrate, we present a web-based interface, geared toward researchers,

that allows for the quick digitization and augmentation of paper documents. By

using any web-based device with a camera or uploading an existing image,

Textension allows the user to create interactive digital objects from analog

texts that retain the look and feel of the originals.

To start this project, we asked ourselves the question: How can we allow users

the ability to interact with both analog and digital text at the same time? Not

knowing exactly what we lose when we digitize a text in terms of interpretation

or cognition is a much larger problem, and we wanted to address how to interact

with these texts without completely discarding the originals. While there are

great efforts to digitize the world’s books, such as the Google books projects

[Google 2017], large-scale OCR projects are difficult to

implement. With the growth of digitized text repositories that leverage these

technologies, two problems are still outstanding: digitally supporting books

that have not yet been digitized, and enabling better use of books that have

been digitized as images and are not currently interactive. The flexibility and

freedom of digital writing and reading are leading to increasing pressure to

digitize texts. However, most of these solutions are costly, time-consuming, and

never seem to reach the document of current interest. There is a need for a

quick, direct and simple way to gain these freedoms with the document you

currently have in hand — whether it is a hand-written letter, an old book, or

the newspaper. What we have laid out here is a method for achieving this goal,

while still having and keeping the original text close at hand.

In this paper, we present a framework that extends the power of the digital to

physical books in near real-time. Our contribution is bringing together ideas

studied in digital document spaces and existing word-scale visualizations to

demonstrate how these known quantities can be leveraged to bridge analog and

digital reading and writing. Our framework is informed by previous results

describing document spaces and the different ways they are used with analog

documents. We outline each of the document spaces and describe how they can be

used in tool design, and we implement a prototype to demonstrate the robustness

of this framework (see Figure 1).

Through Textension we offer quick access, applicable to the analog text at hand,

to an integrated digital/analog environment, only requiring common equipment

such as the camera in a phone and a preferred web-enabled device. Simply

photograph or upload an existing picture of a document, display it in Textension

on a web-browser and start interacting. By making paper documents interactive on

mobile devices Textension allows for a smooth transition between our history and

our present by allowing users a quick way to digitize documents while working

on-site in places like libraries. Our system produces in-line visualizations and

interactive elements directly on the newly built digital document, allowing for

work to continue while having an augmented digital document at the ready.

RELATED WORK

While we present a prototype in this paper, we see our main contribution as a

discussion and amalgamation of what is possible when bringing together analog

and digital affordances as it relates to text. We see Textension as a way to

leverage past studies and computational approaches to natural language to

quickly create digital documents from analog texts using readily accessible

mobile technology.

Paper and Digital Functionality

Bridging the affordances of paper documents and digital technologies is not a

new pursuit. Many projects have attempted to cross the boundaries between

these two modalities to leverage what is best in both.

Early work on Fluid Documents [Chang 1998]

[Zellweger 2000] has provided inspiration for working with

both analog and digital documents. Bondarenko and Janssen provide an

overview of what we can learn from paper to improve digital documents [Bondarenko 2005], specifically important to this framework is

their distinction between the affordances of paper versus digital texts in

terms of task management. Supporting active reading using hybrid interfaces

has been addressed by Hong et al. [Hong 2012], and Shilit et

al. report methods for supporting active reading with freeform digital ink

annotations [Schilit 1998], we leveraged these findings as we

designed and built our prototype. More recently, Metatation was presented as

a pen-based project that supports close reading annotation work on physical

paper with a digital interface [Mehta 2017] and concluded that

pen-based annotations were necessary for the workflow of literary critics.

The difference between active and close reading is small but important.

Active reading is often discussed as a way to engage in cognitive offloading

i.e. note taking, while close reading is a task that is specific to literary

criticism where critics use analysis techniques to decipher meanings within

a text. We developed the Textension framework to be robust enough to allow

for both activities.

Pen-based systems that cross between physical and digital interfaces have

also been explored by Weibel et al. [Weibel 2012], and with

the introduction of gestures in RichReview [Yoon 2014].

Gesture-based interactions have also been addressed in Papiercraft, a system

which enables gesture-based commands on interactive paper [Liao 2008], Pacer, a method for interacting with live images

of documents using hybrid gestures on a cell phone [Liao 2010], and Knotty gestures, which presents subtle traces to support interactive

use of paper [Tsandilas 2010].

Paper-augmented digital documents merge physical annotations on paper with a

digital representation [Guimbretière 2003]. Paper and digital

media have also been used together to support co-located group meetings [Haller 2010]. Work has also been done on applying paper

affordances to digital workspaces such as page flipping and annotations in

e-readers [Hinckley 2012]. The Paper Windows project [Holman 2005] projected digital environments onto physical

paper allowing for the affordances of both. The TextTearing tool [Yoon 2013] was the inspiration for how we create space in

digital documents from analog texts. In our framework, this is done

automatically from a picture of an analog text taken in situ with a

smartphone or tablet and not simply from an electronic version of the

document.

Computer Vision for Document Analysis

Our tool uses several computer vision techniques to aid in the OCR from the

camera of a mobile device. The following papers all describe techniques that

helped us to consider the problems and solutions of in-the-wild document

digitization. Digitizing historical documents is a difficult prospect and

the binarization and filtering techniques presented in da Silva’s work [da Silva 2006] provided guidance on working with older texts as

would be often found in a humanities setting. Also, Gupta discusses OCR

binarization and preprocessing specifically for historical documents [Gupta 2007]. Much work has been done on document capture using

digital cameras including background removal [da Silva 2013],

document image analysis [Doermann 2003], and marginal noise

removal [Fan 2001]. Liang et al. provided a useful survey of

camera-based analysis of text and documents [Liang 2005].

Commercial applications such as the WordLens (now part of Google Translate)

also integrate text processing and analysis [WordLens 2010].

WordLens provides real-time translation of text detected through the mobile

camera, creating an augmented reality environment. We build on this concept

by matching the vision technology with information visualization and natural

language processing tools to enhance document images with rich and

task-specific augmentations.

Post-processing for text documents tends to be idiosyncratic to the documents

themselves. For example, a document with a completely white background may

not need to be gamma corrected. We built into our tool the ability to

control multiple processing parameters. Influence for this decision came

from work such as perspective correction [Jagannathan 2005],

quality assessment and improvement [Lins 2007], and image

segmentation [Lu 2006]. There has also been research on tools

for these kinds of post-processing tasks. Specifically, Photodoc is a

program to aid in document processing acquired by digital cameras [Pereira 2007].

Text Visualization

Text vis is an enormous subsection of information visualization. Rather than

a survey of available text visualizations, we have included a list of

references that directly affected our work and design decisions. Early text

visualizations such as ThemeRiver and TextArc demonstrate novel ways of

visualizing text [Havre 2002]

[Paley 2002]. Sparklines over tag clouds have been previously

presented by Lee et al. [Lee 2010]. Projects such as SeeSoft

[Eick 1992], a text-based tool for visualizing segments of

programming code, gave us an insight into how portions of a document could

be visualized separately to indicate different workspaces. And TileBars [Hearst 1995] showed ways of visualizing document structure at

the sentence level. There has been quite a lot of work visualizing document

collections, but for our purposes, two of the most relevant projects were

Compus [Fekete 2000] and ThemeRiver [Havre 2002]. Compus used XML documents to visualize structure in historical

manuscripts and ThemeRiver depicted thematic changes over time in document

collections. For larger surveys of related work, we suggest the text

visualization survey by Kucher and Kerren [Kucher 2015] and a

specific treatment of text analysis in the Digital Humanities by Jänicke et

al. [Jänicke 2017].

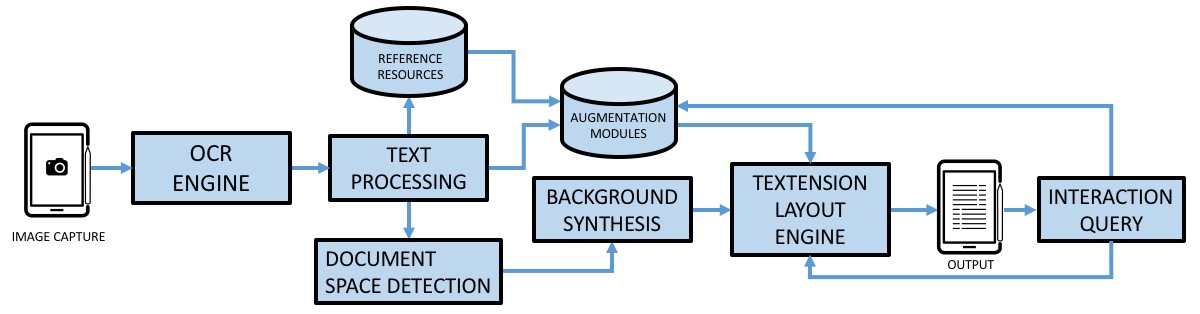

Figure 2.

The Textension framework architecture: images are captured using a

mobile device or webcam. The text is extracted by the OCR engine and the

digitized text is processed using NLP techniques. The background of the

document is detected and synthesized for the insertion of interactive

elements. External resources are brought in as needed to create

augmentations which combine with the document image to create the final

layout on screen. Finally, any interaction queries are fed back to the

layout engine and augmentations and an updated output are

generated.Word-Scale Visualizations

Perhaps the pioneering work in word-scale visualization was Tufte’s proposal

of Sparklines [Tufte 2004], which are small line charts which

reveal trends and work well in small multiples. The different types of

possible word-scale visualizations have been explored by Brandes et al. [Brandes et al 2013], where they discuss the ideas of Gestalt

psychology as it applies to word level visualization. Goffin has explored

implementations and effects of word-scale visualizations in depth [Goffin 2014]

[Goffin 2015]

[Goffin 2015a]

[Goffin 2016]

[Goffin 2017]. These include explorations of the history,

design, placement within a text, the interactive possibilities of word-scale

visualizations, and their impact on reading behavior. Sparkclouds use

word-scale visualizations to show trends as a text visualization [Lee 2010] and Nacenta et al. introduced Fat Fonts, a method

for encoding numerical information on the word-scale directly into the text

itself [Nacenta 2012]. There has also been work on producing

word size graphics for scientific texts [Beck 2017], and a

particularly interesting interaction study that investigates eye movement

while users engage with word-scale visualizations [Beck 2016].

Textension Framework

Previous studies on digital document interaction, annotations, e-readers, and

marginal interactions [Marshall 1997]

[Cheema 2016]

[Goffin 2014]

[Mehta 2017] have identified five spaces that are interacted

with on a digital document: word space, line space, margin space, occlusion

space, and canvas space. Mehta discussed word space, line space, and margin

space as places of interaction for analog annotation [Mehta 2017] after studying literary critics working on poetry

with pen and paper. Goffin et al. use word space and line space as

alternatives for the placement of word-scale visualizations [Goffin 2014]. Occlusion space or the space above the document

has long been an accepted interaction modality, the most famous incarnation

being the everyday tooltip. Goffin et al. use this space to provide enlarged

maps on text documents [Goffin 2014]. Canvas space was

discussed by Cheema et al. in a paper outlining how to extend documents

using external resources such as drag and drop images [Cheema 2016]. While each of these spaces represents a unique

portion of a digital document where interactive elements can be placed,

Textension is a modular system that allows for these elements to be created

interchangeably in all document spaces. Our goal is to demonstrate a

framework where analog documents can be turned into interactive objects in a

short span of time by using the document spaces appropriately.

The Five Interactive Spaces of a Digital Document

From the previous work, we have identified five different types of spaces in

digital documents that can be augmented:

- Word Space: Space inside the bounding boxes of words, lines, and paragraphs.

- Line Space: The space within the bounding box of the text on the page that makes up white space between the lines.

- Margin Space: Space that is outside of the text bounding box but within the boundaries of the document itself.

- Occlusion Space: Any overlay on the document whether permanent or impermanent that covers up the existing text or space.

- Canvas Space: Space that is created outside of the borders of the original text and can be infinitely expanded.

It is important to note when discussing document spaces as part of a larger

framework that they can be used alone or in concert with each other and that

sometimes the lines blur between them. For example, the occlusion space bounding box of a paragraph includes the line spaces from that paragraph and the word spaces above each word. Despite this stacking, it would be

possible, for example, to design annotations which are complementary at each

level.

DEFINING DOCUMENT SPACES

Word Space is any portion of a document that has the printed

word on it. The OCR engine we used, Tesseract, can identify and create bounding

boxes around both printed and hand-written words, lines, and paragraphs.

Depending on the specific implementation, word space could be considered any or

all of these. In an analog book the actual printed type is an element that can

be interacted with cognitively, but as we move into digital representations of

that text it allows us to alter and query the text in interesting ways. The

possibilities here are great, with one of the motivations being simply on-demand

OCR. But when the text is digitized it opens up possibilities for text analysis,

computational linguistics, and machine learning based on language. Marshall et

al. reference both highlighting and annotation as a way that this space is

interacted with on paper documents [Marshall 1997].

Line space is any space that exists between existing printed

lines but remains inside the bounding box of the entire block of printed text on

the page. Digitizing documents using our framework allows for on-demand opening

and closing of these spaces. The manipulation of line space can create room for

additional elements, such as ink annotations, inserted figures, and data

visualizations that relate to the text. We synthesize the background of the

document to avoid jarring the reader, and once this is done effectively any

amount of space can be added to the document. Previous studies have found that

this space is most often used for annotation, specifically in-line notes and for

connectors such as arrows between words.

Margin space is any area outside of the bounding box of the

text but still within the bounds of the original document. This is the space

commonly used for free-form note-taking. For example, when studying, editing, or

conducting a close reading of a document [Mehta 2017]. In addition

to free-form note-taking, this space can be used for inserting new elements

related to the text automatically, such as grammar trees, maps, or simply any

placement of third-party or generated images.

Occlusion space is a layer that covers the document.

Additions in the occlusion space can obscure the text, so semi-transparent and

impermanent elements are appropriate to maintain document legibility. In an

analog setting, the occlusion space is often used with physical additions such

as sticky notes. This space can be accessed in multiple ways, but the underlying

function of the space tends to be information that is needed in the moment, but

not on a continual basis. We demonstrate how to interact with this space by

using tool tips that show the definitions of words on demand. Most of the

techniques we demonstrate in this paper could be taken from one of the other

spaces and placed into occlusion space, the question of permanence or

impermanence will be a decision that rests with the designer.

Canvas space is a concept that we could loosely attribute to

the desk that a printed book is placed on or the space outside a page of text

taped on a whiteboard. When we move to a digital representation of the book, the

canvas space could be infinitely expandable allowing for the insertion of larger

interactive elements. We have chosen to demonstrate how linguistic analysis

could lead to automatic insertion of images, figures, and tables within the

canvas space. It is important to note that external images could also be

inserted in this space as Cheema et al. propose in AnnotateVis [Cheema 2016].

Framework Architecture

For this project, we imagined a tool that scholars of the humanities could

use to do their required work on printed manuscripts, edited collections,

and books, while still having access to digital affordances. Imagine the

scenario where a literary scholar is in a rare book archive and cannot write

directly on the document, or a scenario where a humanist is interested in

the linguistic statistics of a text, but lacks the training to execute the

digitization and processing of a text using code. The latter is one of the

main problems that is ever present within the emerging field of digital

humanities, the roadblock of technical knowledge needed to produce tools. We

set out to build an extensible framework that would allow a humanities

scholar with limited technical knowledge the ability to process, augment,

and export digital versions of analog texts. To achieve this, we bring

together multiple technologies including OCR, machine translation, and

information visualization. By enumerating the set of spaces that can be used

for these techniques and demonstrating their possibilities with examples, we

hope to inspire users to add their own document augmentations to our

existing framework.

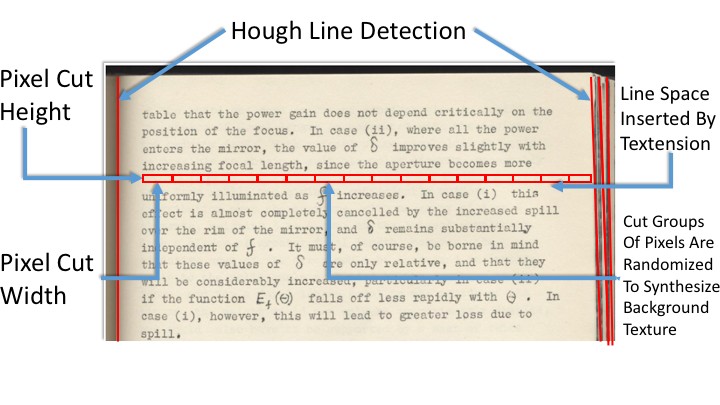

Figure 3.

The space insertion algorithm uses Hough Transform to identify the

x-coordinates of vertical lines in document backgrounds [Duda 1972]. pixel cut height and pixel

cut width measure the height and width in pixels of the

background crop used for background synthesis. These parameters can be

adjusted for different documents because of localized color and lighting

effects.The Textension framework starts with a document image, processes the image to

discern both the content as well as the use of space on the page, adds space

to the page as needed, and creates augmentations, both static and

interactive, to insert into the newly digital object. The resulting

processed image is presented to the user for further exploration,

annotation, and interaction. The framework architecture is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Textension Prototype

We provide a specific implementation of Textension in a web-based system

which offers a selection of document augmentations and interactive tools,

which we will describe in this section.

Image Capture and Processing

When a user comes to the opening screen of Textension they are presented

with two input options. They can either use the camera that is built

into their device (webcam, phone camera, front facing tablet camera) and

take a snapshot of the document they wish to process, or they can upload

an image file that has been previously prepared. Document images can be

single or multiple pages and are uploaded with a drag and drop

interface. The next stage of document processing begins immediately

after the upload completes. The system uses image processing from the

Python Image Library and image manipulation from OpenCV. We have found

that a combination of binarization, grey-scaling, and image sharpening

have had a noticeable effect on the results of the OCR, which is the

next stage of processing.

OCR engine

We used the open source Tesseract OCR engine in the Textension prototype.

Smith provides an overview and a history of the development of the

engine [Smith 2007]

[Smith 2013], and Patel et al. provide a case study

approach for its use [Patel 2012]. Tesseract can be

trained with many different languages and also with handwriting, making

it a robust choice for an implementation such as this.

While great effort is being taken by many companies to digitize the

world’s books, this process is expensive, hardware dependent, and

time-consuming. The Tesseract OCR engine provides high-quality open

source OCR in a local setting for printed and hand-written text. Often

when working between analog and digital platforms scholars are forced to

type passages out, for example, to extract a quote from a book for

insertion into a manuscript. This is due to the fact that many digital

book readers do not give you access to text that can be copy and pasted

for copyright reasons, or in some cases, only images of paper documents

are provided. Our domain expert has been using Textension to quickly

digitize small portions of text for inclusion into working documents.

This application of Textension allows for easy transfer of quotable

information from analog books to digital platforms using only the OCR

functionality. In addition, the OCR engine provides the content in a

machine-readable form for later linguistic processing, linking, and

other augmentations. Tesseract also provides bounding boxes for each

word, which we use to identify document spaces.

Background Synthesis

In order to augment documents with helpful annotations, or to provide

space for users to make pen-based annotations, document spaces often

need to be enlarged. This is not possible when working with an analog

document. However, in the digital version, we can manipulate the image

to provide the needed space. For example, to place a translation of text

between lines, the inter-line spacing first needs to be increased.

Document backgrounds can be complicated, with changing lighting

conditions almost guaranteed using mobile phone and tablet cameras. To

retain the original look of the document image, we created a method for

inserting space by synthesizing sections of the document background

which seamlessly integrate with the original. These regions can be

optionally clearly noted, for example by using a different color. This

may be preferable in situations where differentiating the original

document from manipulations is important, for example in archival and

preservation work. Background pre-processing is a computationally

intensive process, so an option for low or high-resolution processing is

included. Low-resolution processing is suitable for quick interactive

applications, where high-resolution processing is more suitable for

printing and saving the results of an analysis session.

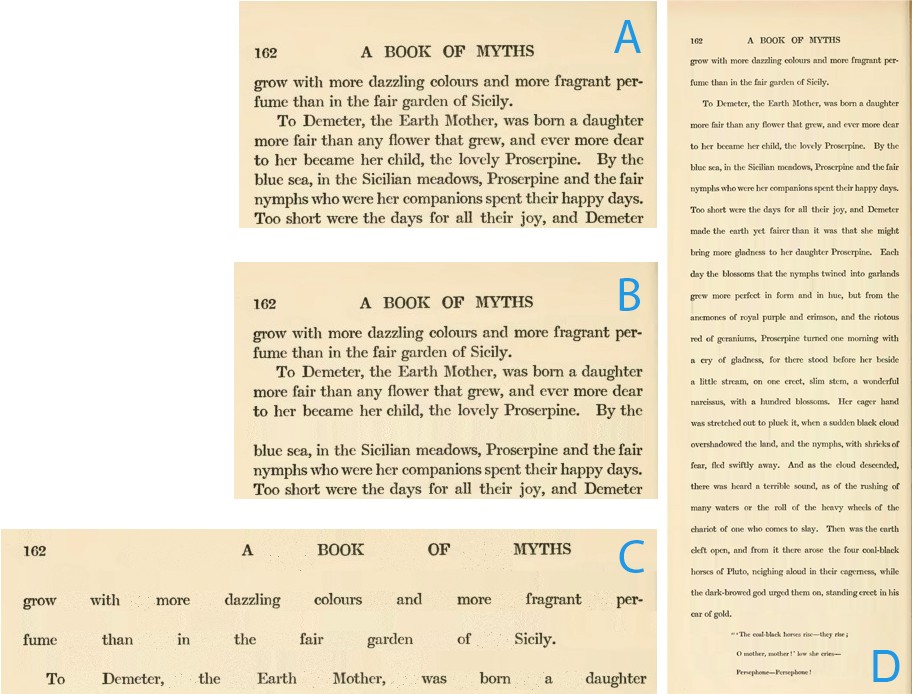

Figure 4.

A. Original document image. B. A single line space inserted. C.

Horizontal word space and vertical line space inserted into the

document. D. The whole page with all line spaces opened.To improve image capture quality, which can affect background synthesis,

we provide the user with a frame to set their image in. While it is

possible to adjust skew correction and automatically crop text from

images, we found from our internal testing that forcing the user to

frame the image themselves resulted in much better OCR and therefore a

much better experience. There is precedence for this type of interaction

in commercial settings such as remote cheque deposits for online

banking, where a user is forced to frame and focus the cheque before the

system will accept the image. Once we have the image we use the bounding

boxes provided by the OCR engine to rebuild the document in image

fragments within the web platform. Each space and word is modeled

separately to allow us to manipulate those elements within the

browser.

The important image regions for the space insertion algorithm are

illustrated in Figure 3. To expand the

space between the lines (expand line space) in

high-resolution mode we first use Hough line detection to identify

x-values where vertical lines exist on the page [Duda 1972]. The Hough transform is a feature extraction technique to find

instances of objects within a certain class of shapes (vertical lines in

our application) by a voting procedure. This allows us to maintain the

edges of pages and also to recreate lighting conditions near the bound

edges as we expand space within the document.

The algorithm then copies a slice of the image from between each

individual line from one edge of the page to the other. The height of

the slice (the pixel cut height ) is set to the height of

the unimpeded space between the bounding boxes of the lines of text

above and below. For the low-resolution processing, copies of this slice

are inserted vertically to create space in the document. Depending on

the complexity of the background this process is sometimes adequate.

However, in most cases, this results in image streaking, which is usable

for testing and exploration, but can be distracting and is not

sufficient for photo realistic background additions.

As local lighting and color effects are so prevalent in scanned and

photographed documents, especially historical documents, we wanted to

model the backgrounds from as local a position as possible. The

intuition behind our approach is that we can randomly reorder pixels in

a local region to reduce streaking while retaining local lighting. From

the extracted slice of the document, we select a patch of the original

image that has the dimensions of pixel cut height by

pixel cut width. To insert a new patch below it we

simply randomize the pixels from the current patch and insert it. As we

scan across the line we continue this in increments of pixel cut

width until the line is complete. The one exception is when

the patch location falls within a definable threshold of the x-values of

the vertical lines found by the Hough line algorithm at the start of the

process. In this case, the pixels in that patch are not randomized but

rather copied, to retain the sharpness of the detected edge. This allows

us to sample local lighting effects in the background of the image. For

adding horizontal space between words a similar process is used. When

space is added only between two words on a single line, we also add the

same amount of space to all lines by distributing it across all

inter-word spaces. This preserves the original justification of the

document (see Figure 4).

The pixel cut height and pixel cut width

parameters control the locality of the modeling. Reasonable defaults are

provided, but they can be varied in the settings screen to obtain the

best result.

We have also found that artifacts on the page disrupt the color balance

within each individual cut and can affect the quality of the background

rendering. We offer the option of removing artifacts on the input

screen. To remove blemishes on the page, the cropped line is binarized,

any pixels that turn black in the binarization process are not used

within the color randomization that synthesizes the background color.

This leaves the original artifact but does not propagate it during the

space insertion process.

Background synthesis and artifact removal are pre-processed across all

candidate regions of the document to a pre-set threshold of inserted

space. The synthesized image data is stored for quick access and

insertion during document augmentation and interaction.

LAYOUT ENGINE

After creating an interactive, expandable document from the captured image,

augmentations can be added to provide supportive features as required for the

specific task and context. For example, a learner may require word definitions,

while a literary scholar may be interested in the contemporary use of the words

in the document. Augmentations can take the form of inserted glyphs, images,

overlays, and annotations in the document spaces, or they may replace or change

the words in the document. Augmentations can be temporary or permanent, as

appropriate for their purpose and the document space in which they appear. The

insertion and placement of augmentations and the provision of interactivity on

the document and its augmentations is provided by the layout engine (see Figure 5).

The images after upload are broken into individual word and space objects that

are then recompiled in order onto an HTML canvas to reproduce the original image

with the added flexibility of moving, inserting, and changing elements.

Augmentations are placed on the canvas as a layer on top of the image objects.

Textension has been developed to support the creation of new augmentations,

which can draw on custom data processing, local datasets, or public APIs and

data. Textension was built using flask, a python server back-end; bootstrap, for

UI elements; jinja, a template engine for python; and jquery, for data

handling.

DOCUMENT AUGMENTATIONS

What we present in this section are a series of concrete implementations of

document augmentations that demonstrate a subset of the possibilities of the

Textension framework. The selected examples highlight the possible breadth

available when considering the five document spaces and the possibilities for

interaction with those spaces. We explore insertion augmentations, as well as

temporary and permanent overlays. The availability of the plain text allows easy

integration of natural language processing, and the fact that the digital

document is built in pieces allows for easy insertion of space to accommodate

for the adding of new features. In this way, we envision Textension as both a

sandbox for designing interactive elements for digital documents and a way to

use both digital and analog affordances simultaneously when working with texts.

Insertion of Space

To allow for interaction with books off the shelf we wanted to cross over

between digital and analog affordances. The ability to write notes directly

on the pages of a book is one of the analog affordances that is constantly

used, much to the dismay of librarians throughout the world. As seen in

studies by Marshall [Marshall 1997] and Mehta [Mehta 2017], there are workflows that depend on this type of

interaction. Due to space constraints on the printed page, these annotations

often take the form of writing in the margins of the text or squeezing into

the spaces between the printed lines. For the digital version of the text,

we wanted to enhance the ability to write on the page in both the line space and the margin space.

The pre-processed background is used to insert space within the text, to

allow for writing notes or inserting elements such as maps.

There are two ways to insert space in Textension. The first is to simply tap

and hold on a line with the stylus, or click with a mouse and that line will

open up allowing space for writing. This works both vertically and

horizontally; the trigger for vertical line creation is in the space between

lines and for the horizontal space insertion it is in the space between

words (see Figure 4). The size of the space to

be added is determined in the parameter settings for the tool. By default,

we have set the opening increment at 20 pixels. Inserted space is both

editable as a text box by clicking on it, or by toggling the draw mode space

can be written in any way the user chooses (see Figure 6). The second method is to open all spaces of a given

type (e.g. line spaces) through a menu function. Spaces can also be inserted

by other augmentations which require space. For example, inserting space is

a precursor to inserting translations between lines. Together, these methods

allow for flexible interaction that can be used for editing and

annotation.

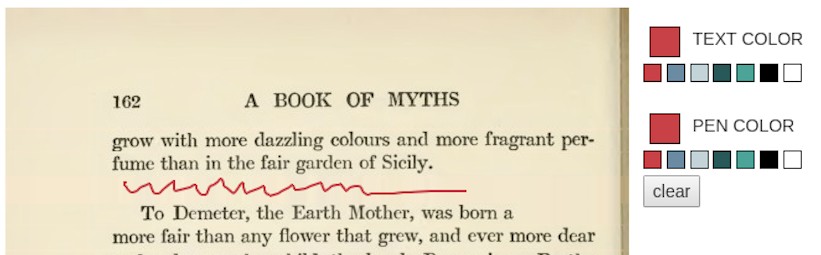

Drawing and Typing on the Document

Once space has been opened up we wanted to maintain the ability to type and

write on the document. Both functions have a toggle and a color picker that

allows for this type of interactivity. You can draw anywhere on the

document, but typing has been constrained to text boxes that have been

created in the new space of the document (see Figure

6).

OCR Confidence

Often when digitizing analog texts OCR confidence is very important.

Textension provides a feature where users can see an overlay of how

uncertain the OCR algorithm was for each word. This augmentation is

displayed as an overlay in the word space. The darker

the color the less confident the score. This mapping was designed to draw

attention to and “obscure” those words that the system

had difficulty recognizing. With the current trend in machine learning and

the relative anxiety that is brought with black box algorithms, showing the

inner workings of the OCR engine is a way to both help the user understand

how the system is working but also where exactly work may need to be done to

make for a better user experience and digital document (see Figure 5).

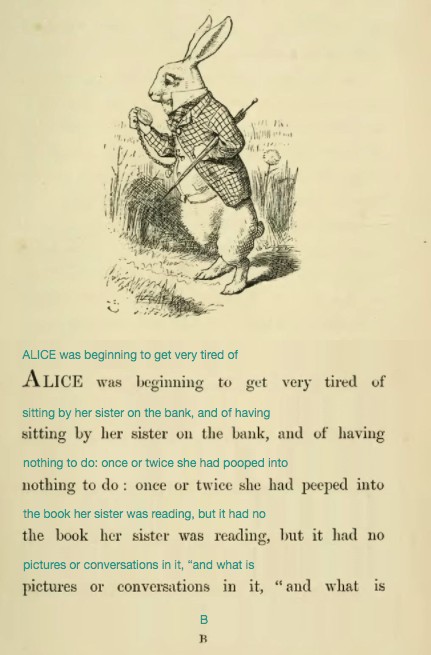

OCR Text

While the OCR confidence overlay can allow users to understand how well their

scan has been processed, we added another feature that works in concert with

the previous ones to place text within the line space.

The OCR text feature will spread all the lines in the document and insert

the OCR text into editable text boxes (see Figure

7). The user can then correct the OCR directly on the newly built

document and export the finished text into a text file. Our own project’s

domain expert is already using this feature to solve the problem of not

being able to cut and paste from digital books while writing Humanities

essays. He has been taking pictures of quotations from physical copies of

the books and exporting the OCR directly into a word processor.

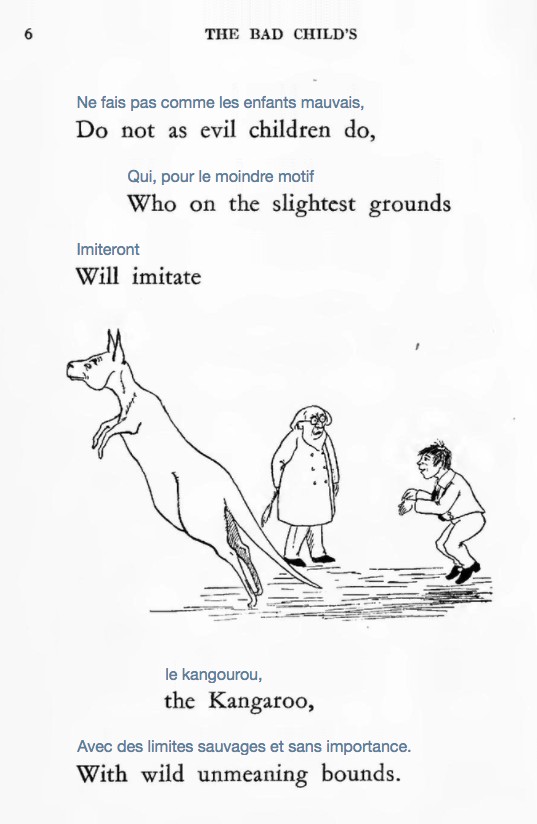

Translation

Once the user has tuned the OCR to their liking, they can toggle the

auto-translate menu button which will then use the Google translate API and

automatically insert a translation of the text in the line

space (see Figure 8). This method

works for all of the languages currently supported by Google and its one

limitation is typographical, in that books often split words on the end of

lines. Future work will address this limitation.

Manual Removal and Replacement of Words

The manipulation of the word space on the level of the

text is an option that could be used in many scenarios. This widget provides

the ability to select an individual word, erase it from the document image,

and substitute in a word provided by the user. New words are scaled to fit

into the space of the existing word and are highlighted to show that they

were additions. Possible scenarios for this type of inclusion could be

manual translation, gender pronoun switching or switching between the Latin

and common names of scientific organisms.

Location-Based Maps

With named entity recognition, we demonstrate the power of digital

affordances with photographed texts by inserting maps. During

pre-processing, we detect and store place names within the text. When the

map feature is toggled Textension highlights the place name in the document,

and automatically inserts a map from the Google maps API directly into the

document in the margin space. This feature is a

demonstration of the power of combining existing technology, such as the

Google maps API with automatic document space expansion. Because the

document is built in pieces we can freely move interactive elements into

different document spaces to see which works best for the specific

implementation.

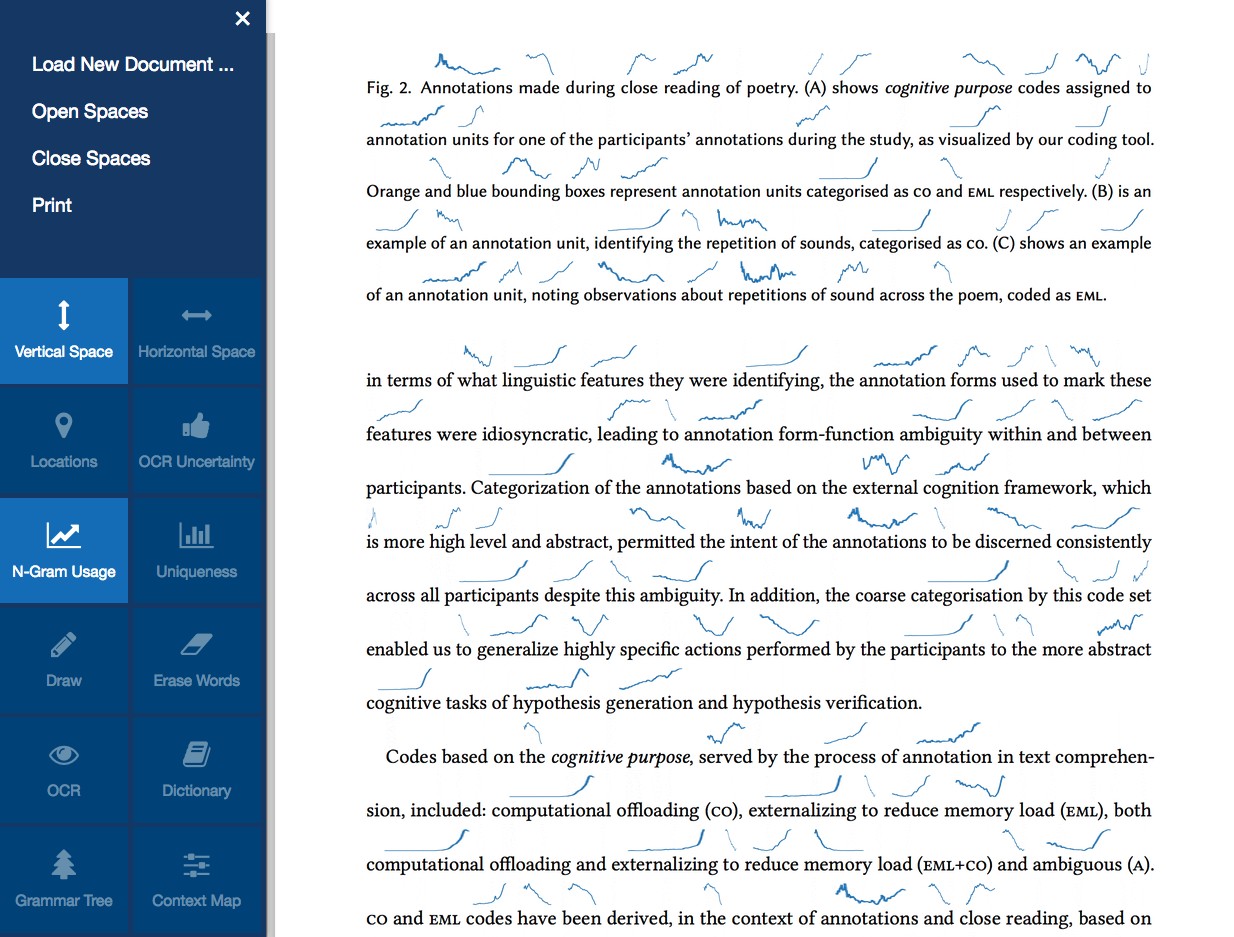

Sparklines

Word space visualizations have been showing promise as

ways to augment digital texts [Goffin 2014] Textension offers

the ability to automatically insert these visualizations into images of

analog texts. We have chosen to implement lexical usage sparklines [Tufte 2004] directly above each word showing the usage within

the Google Books corpus from 1800–2012 (see Figure

9). This technique could be used for many different types of

visualizations limited only by the power of the OCR and NLP techniques

available.

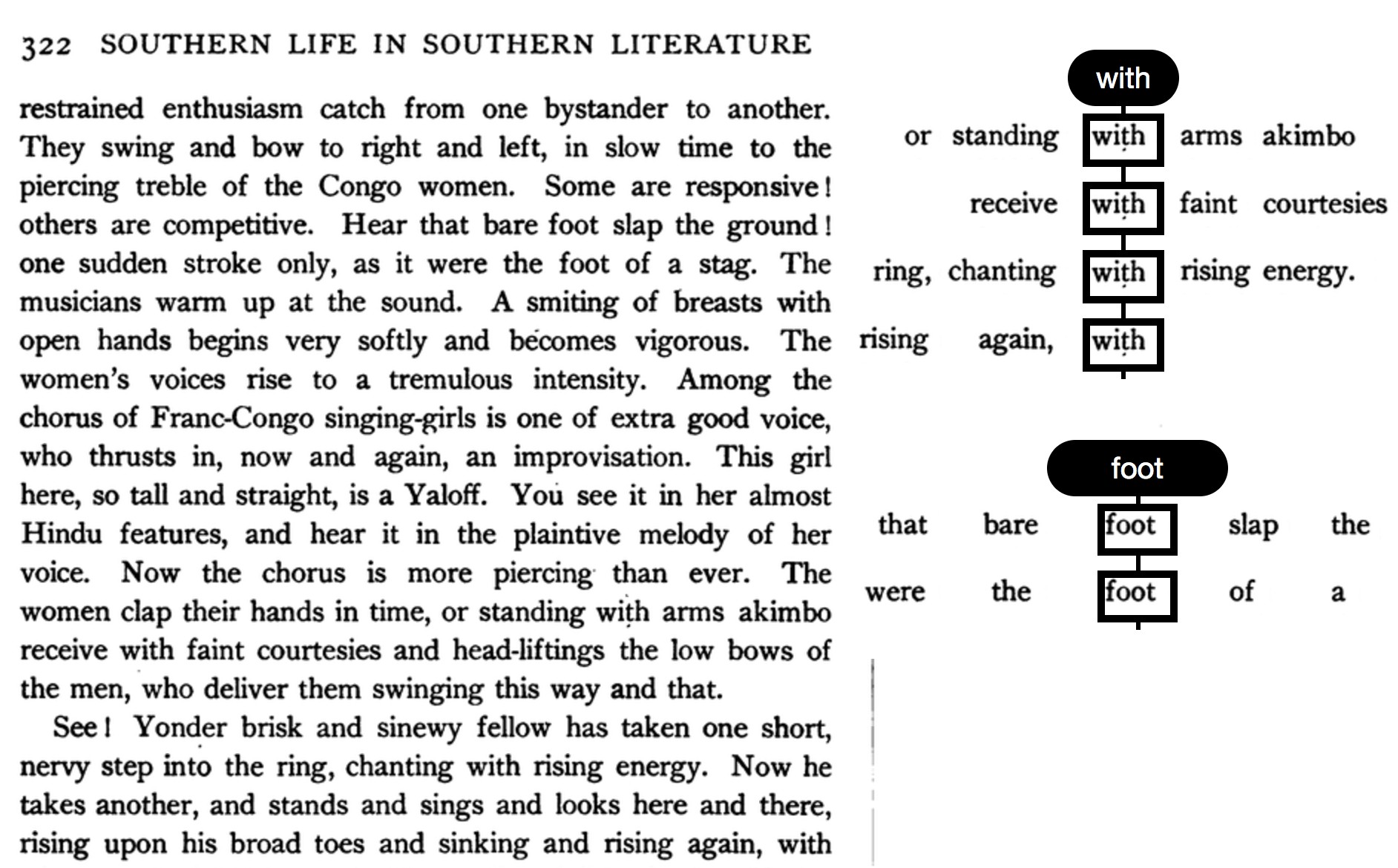

Context Maps

A context map lists all of the ways that a particular word or phrase has been

used within a document. This digital affordance uses canvas

space to build interactive concordance lines that highlight the

four words before and after the word in question. The maps are built using

the images patches of words in the document to maintain the document

aesthetics and reduce the impact of OCR errors. This is an example of the

types of things that can be done with ready access to linguistic information

and expandable canvas space (see Figure

10).

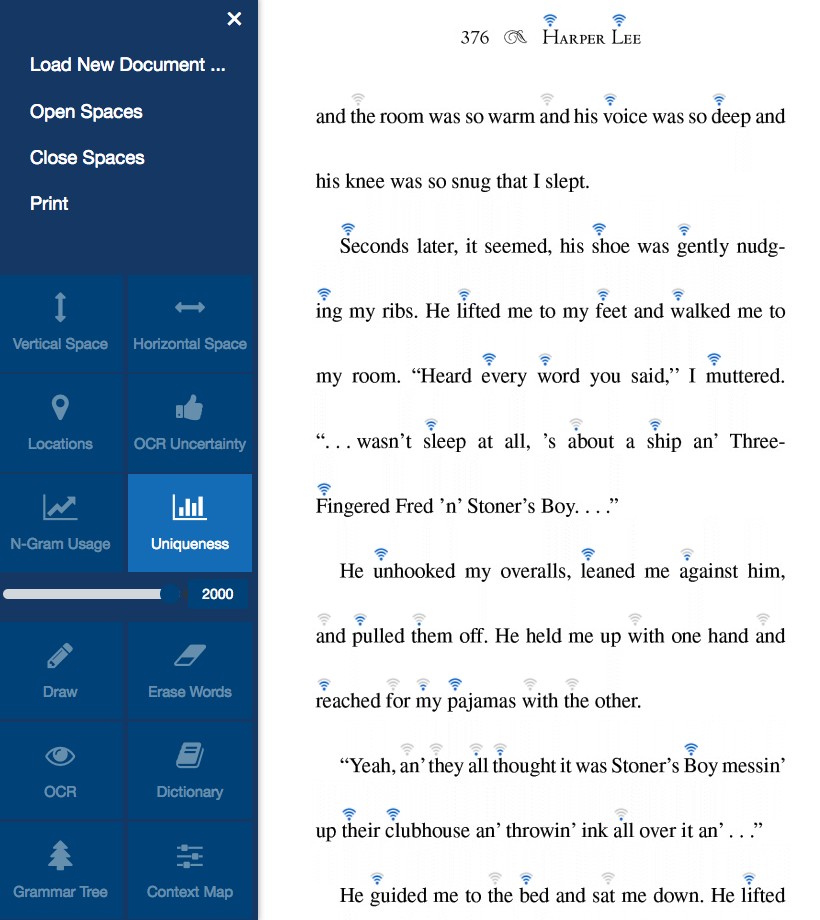

Lexical Uniqueness Glyphs

The second word space visualization we implemented was

showing the uniqueness of each word within the language (see Figure 11). When this mode is toggled active

the user is given two time sliders, one for the upper and one for the lower

bounds of the time in question and small bar charts are automatically

inserted for each word in the document. Each chart is a relative

representation of the word’s uniqueness within the given document, meaning

that as the upper and lower bounds time sliders are adjusted, each glyph

will adjust relative to the other. This type of interaction could be

adjusted to address specific historical questions from literary scholars and

could be extended to display anything that has data relating to the text.

Possible scenarios for this include showing etymological information, usage

information, or using color as a visual variable to display languages of

origin.

Word Definitions

To demonstrate the possibilities of the occlusion space

we have implemented a widget that allows the user to hover on a word within

the newly digitized document and get dictionary information scraped from

Webster’s Online Dictionary API [Webster’s 2017]. This space

will often be used for impermanent information that the user will need once,

such as a definition, and then can disappear (see Figure 5).

Print, Save, and Download

As the features are toggled on and off within the tool, the user is given the

option to save both editable text as an external text document but also

high-resolution images of the current state within the program. The user has

the option to export whatever document state that they create. Many features

of Textension can be used at the same time so it is possible to create and

export multiple variations of a single document.

CONCLUSION

The tension that exists between our analog pasts and our digital present can be

addressed using our framework. Our prototype, Textension, leverages the power of

OCR and digitally manipulates the five document spaces in near real-time. The

system we present is an implementation of previous studies brought together in a

way that can be extended easily for domain-specific analysis tasks. The

web-based platform allows for easy integration with mobile technology and makes

it possible to use Textension in a variety of locations and scenarios. We have

demonstrated a breadth of possible use cases and have chosen widgets that

demonstrate the utility of each of the document spaces.

Discussion

Textension can be used in situations where quick digitization is necessary

and digital versions may not be available, such as within the stacks of a

university library. The web-based framework allows for easy document

digitization using any web-enabled camera. This could be on a mobile phone

or a desktop computer with a webcam. The system also allows for the

uploading of previous digitized texts. The drag and drop interface allows

for the uploading of PDF’s and digital images providing a robustness of

input possibilities. The provided text augmentations support humanities

activities such as annotation and close reading. By bringing in linked

reference resources such as maps and lexical uniqueness scores, Textension

can situate an unknown text in the greater spatial and linguistic context,

assisting with tasks associated with “distant reading”

[Moretti 2005].

Future Work

While we designed Textension to demonstrate the usefulness and power of

bringing together affordances from paper and digital documents, there are

still several ways that we can expand the system. The first is by using

larger canvases. Textension focuses on space within documents and provides a

limited extended canvas space. An infinite canvas workspace, such as the

zoomable interface of PAD++ [Bederson 1994], could allow for

insertion of more than one document image in the same workspace, and the

addition of larger and more sophisticated interactive visualizations.

The second addition that we envision is to apply these techniques in the

opposite direction, namely to augment digital books with the same types of

interactive elements. We have already seen some of these approaches within

existing e-readers like Amazon’s Kindle, but there is a lot of room to

experiment with that design space. Another welcome addition would be

horizontal space organization to solve problems like line breaks when using

the Google Translate API. Because the OCR uses lines as an organizing

principle, hyphenated words often disrupt the OCR and the translation

algorithm. Reconnecting hyphenated words would require reflowing the

document to maintain a justified layout.

A final addition that would solve a problem in the digital humanities is to

provide a way to easily create new augmentations for Textension so that

users with limited programming abilities would be able to add features to

the interface. The current implementation makes it easy to add new features

with modest programming skills, but we would like to make that more

accessible in the future.

Works Cited

Beck 2016 F. Beck, Y. Acurana, T. Blascheck, R.

Netzel, and D. Weiskopf. 2016. An expert evaluation of word-sized visualizations

for analyzing eye movement data. In IEEE Workshop on Eye

Tracking and Visualization (ETVIS). IEEE, 50–54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ETVIS.2016.7851166

Beck 2017 F. Beck and D. Weiskopf. 2017. Word-Sized

Graphics for Scientific Texts. IEEE Trans. on Visualization

and Computer Graphics 23, 6 (June 2017), 1576–1587. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2017.2674958

Bederson 1994 Benjamin B. Bederson and James D.

Hollan. 1994. Pad++: A Zooming Graphical Interface for Exploring Alternate

Interface Physics. In Proc. ACM Symp. on User Interface

Software and Technology (UIST). ACM, 17–26. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/192426.192435

Bondarenko 2005 Olha Bondarenko and Ruud

Janssen. 2005. Documents at Hand: Learning from Paper to Improve Digital

Technologies. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (CHI). ACM, 121–130. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1054990

Brandes et al 2013 Ulrik Brandes, Bobo Nick,

Brigitte Rockstroh, and Astrid Steffen. 2013. Gestaltlines. In Proc. Eurographics Conf. on Visualization (EuroVis).

171–180. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cgf.12104

Chang 1998 Bay-Wei Chang, Jock D. Mackinlay, Polle

T. Zellweger, and Takeo Igarashi. 1998. A negotiation architecture for fluid

documents. In Proceedings of the 11th annual ACM symposium

on User interface software and technology (UIST '98). ACM, New York,

NY, USA, 123-132. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/288392.288585

Cheema 2016 Muhammad Faisal Cheema, Stefan

Jänicke, and Gerik Scheuermann. 2016. AnnotateVis: Combining Traditional Close

Reading with Visual Text Analysis. In IEEE VIS Workshop on

Visualization for the Digital Humanities. 4.

Doermann 2003 D. Doermann, Jian Liang, and

Huiping Li. 2003. Progress in camera-based document image analysis. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Document Analysis and Recognition

(ICDAR). 606–616. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2003.1227735

Duda 1972 R. O. Duda and P. E. Hart. 1972. Use of

the Hough Transformation to Detect Lines and Curves in Pictures. Comm. ACM 15 (Jan. 1972), 11–15.

EEBO 2003 EEBO - Early English Books Online. http://eebo.chadwyck.com/home.

(2003). Accessed: 2017-09-18.

Eick 1992 S. C. Eick, J. L. Steffen, and E. E.

Sumner. 1992. Seesoft-a tool for visualizing line oriented software statistics.

IEEE Trans. on Software Engineering 18, 11

(Nov. 1992), 957–968. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/32.177365

Fan 2001 Kuo Chin Fan, Yuan Kai Wang, and Tsann Ran

Lay. 2001. Marginal noise removal of document images. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR).

317–321. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2001.953806

Fekete 2000 Jean Daniel Fekete and Nicole

Dufournaud. 2000. Compus: Visualization and Analysis of Structured Documents for

Understanding Social Life in the 16th Century. In Proc. ACM

Conf. on Digital Libraries (DL). ACM, 47–55. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/336597.336632

Goffin 2014 Pascal Goffin, Wesley Willett,

Jean-Daniel Fekete, and Petra Isenberg. 2014. Exploring the placement and design

of word-scale visualizations. IEEE Trans. on Visualization

and Computer Graphics 20, 12 (2014), 2291–2300.

Goffin 2015 Pascal Goffin, Wesley Willett,

Jean-Daniel Fekete, and Petra Isenberg. 2015. Design Considerations for

Enhancing Word-Scale Visualizations with Interaction. Posters of Conf. on

Information Visualization (InfoVis). (Oct. 2015). Poster.

Goffin 2015a Pascal Goffin, Wesley Willett, and

Petra Isenberg. 2015a. Sharing information from personal digital notes using

word-scale visualizations. In Proc. IEEE VIS Workshop on

Personal Visualization: Exploring Data in Everyday Life. https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01216223/

Goffin 2015b Pascal Goffin, Wesley Willett,

Anastasia Bezerianos, and Petra Isenberg. 2015b. Exploring the Effect of

Word-Scale Visualizations on Reading Behavior. In Proc. ACM

Conf. Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA

’15). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1827–1832. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2702613.2732778

Goffin 2016 Pascal Goffin. 2016. An Exploration of Word-Scale Visualizations for Text

Documents. Ph.D. Dissertation. Université Paris-Saclay. http://www.theses.fr/2016SACLS256

Goffin 2017 P. Goffin, J. Boy, W. Willett, and P.

Isenberg. 2017. An Exploratory Study of Word-Scale Graphics in Data-Rich Text

Documents. IEEE Trans. on Visualization and Computer

Graphics 23, 10 (Oct 2017), 2275–2287. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2016.2618797

Google 2017 Google Books. https://books.google.ca/. (2017).

Accessed: 2017-09-18.

Guimbretière 2003 François Guimbretière.

2003. Paper Augmented Digital Documents. In Proc. ACM Symp.

on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST). ACM, 51–60. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/964696.964702

Gupta 2007 Maya R. Gupta, Nathaniel P. Jacobson,

and Eric K. Garcia. 2007. OCR binarization and image pre-processing for

searching historical documents. Pattern Recognition

40, 2 (2007), 389–397. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2006.04.043

Haller 2010 Michael Haller, Jakob Leitner, Thomas

Seifried, James R. Wallace, Stacey D. Scott, Christoph Richter, Peter Brandl,

Adam Gokcezade, and Seth Hunter. 2010. The NiCE Discussion Room: integrating

Paper and Digital Media to Support Co-Located Group Meetings. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems

(CHI). ACM, 609–618. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753418

Havre 2002 Susan Havre, Elizabeth Hetzler, Paul

Whitney, and Lucy Nowell. 2002. ThemeRiver: Visualizing Thematic Changes in

Large Document Collections. IEEE Trans. on Visualization

and Computer Graphics 8, 1 (Jan. 2002), 9–20. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/2945.981848

Hearst 1995 Marti A. Hearst. 1995. TileBars:

Visualization of Term Distribution Information in Full Text Information Access.

In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems

(CHI). ACM, 59–66. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/223904.223912

Hinckley 2012 Ken Hinckley, Xiaojun Bi, Michel

Pahud, and Bill Buxton. 2012. Informal Information Gathering Techniques for

Active Reading. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (CHI). ACM, 1893–1896. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208327

Holman 2005 David Holman, Roel Vertegaal, Mark

Altosaar, Nikolaus Troje, and Derek Johns. 2005. Paper Windows: Interaction

Techniques for Digital Paper. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on

Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). ACM, 591–599. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1055054

Hong 2012 Matthew Hong, Anne Marie Piper, Nadir

Weibel, Simon Olberding, and James Hollan. 2012. Microanalysis of active reading

behavior to inform design of interactive desktop workspaces. In Proc. ACM Conf. on Interactive Tabletops and Surfaces

(ITS). 215–224. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2396636.2396670

Jagannathan 2005 L Jagannathan and CV

Jawahar. 2005. Perspective correction methods for camera based document

analysis. In Proc. Int. Workshop on Camera-based Document

Analysis and Recognition. 148–154.

Jänicke 2017 S. Jänicke, G. Franzini, M. F.

Cheema, and G. Scheuermann. 2017. Visual Text Analysis in Digital Humanities.

Computer Graphics Forum 36, 6 (2017), 226–250.

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cgf.12873

Kucher 2015 K. Kucher and A. Kerren. 2015. Text

visualization techniques: Taxonomy, visual survey, and community insights. In

Proc. IEEE Pacific Visualization Symp.

(PacificVis). 117–121. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/PACIFICVIS.2015.7156366

Lee 2010 Bongshin Lee, Nathalie Henry Riche, Amy K.

Karlson, and Sheelash Carpendale. 2010. SparkClouds: Visualizing Trends in Tag

Clouds. IEEE Trans. on Visualization and Computer

Graphics 16, 6 (Nov. 2010), 1182–1189. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2010.194

Liang 2005 Jian Liang, David Doermann, and Huiping

Li. 2005. Camera-based Analysis of Text and Documents: A Survey. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recognit. 7, 2-3 (July 2005),

84–104. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10032-004-0138-z

Liao 2008 Chunyuan Liao, François Guimbretière, Ken

Hinckley, and Jim Hollan. 2008. Papiercraft: A Gesture-based Command System for

Interactive Paper. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum.

Interact. 14, 4, Article 18 (Jan. 2008), 27 pages. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1314683.1314686

Liao 2010 Chunyuan Liao, Qiong Liu, Bee Liew, and

Lynn Wilcox. 2010. Pacer: Fine-grained Interactive Paper via Camera-touch Hybrid

Gestures on a Cell Phone. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). ACM, 2441–2450. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753696

Lins 2007 R. Lins, G. P. e. Silva, and A. R. Gomes e

Silva. 2007. Assessing and Improving the Quality of Document Images Acquired

with Portable Digital Cameras. In Proc. Int. Conf. on

Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Vol. 2. 569–573. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2007.4376979

Lu 2006 Shijian Lu and Chew Lim Tan. 2006. The

Restoration of Camera Documents Through Image Segmentation. In Proc. Int. Workshop on Document Analysis Systems

(DAS). Springer, 484–495. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/11669487_43

Marshall 1997 Catherine C. Marshall, Annotation:

From paper books to the digital library. In Proc. ACM Conf.

on Digital Libraries (DL). ACM. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/263690.263806

Mehta 2017 Hrim Mehta, Adam James Bradley, Mark

Hancock, and Christopher Collins. 2017. Metatation:

Annotation as Implicit Interaction to Bridge Close and Distant Reading.

in (TOCHI) ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. Volume 24

Issue 5, November 2017, Article No. 35.

Moretti 2005 Franco Moretti. 2005. Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary

History. Verso, Brooklyn, NY.

Nacenta 2012 Miguel Nacenta, Uta Hinrichs, and

Sheelagh Carpendale. 2012. FatFonts: Combining the Symbolic and Visual Aspects

of Numbers. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Advanced Visual

Interfaces (AVI).

Paley 2002 W. Bradford Paley. 2002. TextArc:

Showing word frequency and distribution in text. In: Posters of IEEE Conf. on

Information Visualization. (2002).

Patel 2012 Chirag Patel, Atul Patel, Dharmendra

Patel, Archana A. Shinde, Hui Wu, and Jian Liang. 2012. Optical Character

Recognition by Open source OCR Tool Tesseract: A Case Study. Int. Journal of Computer Applications 40, 10

(2012).

Pereira 2007 Gabriel Pereira and Rafael Lins.

2007. PhotoDoc: A Toolbox for Processing Document Images Acquired Using Portable

Digital Cameras. In Camera Based Document Analysis and

Recognition. 107–115.

Schilit 1998 Bill N. Schilit, Gene Golovchinsky,

and Morgan N. Price. 1998. Beyond Paper: Supporting Active Reading with Free

Form Digital Ink Annotations. In Proc. SIGCHI Conf. on

Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). ACM, 249–256. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/274644.274680

Smith 2007 R. Smith. 2007. An Overview of the

Tesseract OCR Engine. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Document

Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Vol. 2. 629–633. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2007.4376991

Smith 2013 Ray W. Smith. 2013. History of the

Tesseract OCR engine: What worked and what didn’t. Proc.

SPIE 8658 (2013), 865802–865802–12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/12.2010051

Tsandilas 2010 Theophanis Tsandilas and Wendy

E. Mackay. 2010. Knotty Gestures: Subtle Traces to Support Interactive Use of

Paper. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Advanced Visual Interfaces

(AVI). ACM, 147–154. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1842993.1843020

Tufte 2004 Edward Tufte. 2004. Sparklines: Intense,

simple, word-sized graphics. In Beautiful Evidence.

46–63.

Webster’s 2017 Webster’s Online Dictionary API.

https://www.dictionaryapi.com/. (2017). Accessed: 2017-09-18.

Weibel 2012 Nadir Weibel, Adam Fouse, Colleen

Emmenegger, Whitney Friedman, Edwin Hutchins, and James Hollan. 2012. Digital

Pen and Paper Practices in Observational Research. In Proc.

SIGCHI Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). ACM,

1331–1340. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208590

WordLens 2010 WordLens. Software application.

(2010). https://questvisual.com/

Accessed: 2017-09-08.

Yoon 2013 Dongwook Yoon, Nicholas Chen, and Francois

Guimbretière. 2013. TextTearing: opening white space for digital ink annotation.

In Proceedings of the 26th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and

technology (UIST '13). ACM, New York, NY, USA,107-112. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2501988.2502036

Yoon 2014 Dongwook Yoon, Nicholas Chen, François

Guimbretière, and Abigail Sellen. 2014. RichReview: Blending Ink, Speech, and

Gesture to Support Collaborative Document Review. In Proc.

ACM Symp. on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST). ACM,

481–490. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2642918.2647390

Zellweger 2000 Polle T. Zellweger, Susan

Harkness Regli, Jock D. Mackinlay, and Bay-Wei Chang. 2000. The impact of fluid

documents on reading and browsing: an observational study. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (CHI '00). ACM, New York, NY, USA,249-256.

DOI=http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/332040.332440

da Silva 2006 João Marcelo M. da Silva, Rafael

Dueire Lins, and Valdemar Cardoso da Rocha. 2006. Binarizing and Filtering

Historical Documents with Back-to-front Interference. In Proc. ACM Symp. on Applied Computing (SAC ’06). ACM, 853–858. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1141277.1141471

da Silva 2013 Gabriel de França Pereira da Silva,

Rafael Dueire Lins, and André Ricardson Silva. 2013. A new algorithm for

background removal of document images acquired using portable digital cameras.

In Proc. Int. Conf. on Image Analysis and Recognition

(ICIAR). Springer, 290–298. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39094-4_33