3 Data and Workflow

The empirical case study in this article is based on New Year’s speeches of the three

German-speaking countries, Germany, Austria and Switzerland

[2]

covering the years from 2000 to 2021. These three countries were selected, first,

based on the shared language providing us the possibility to compare the use of

language of high politics across these countries. Second, all three countries belong

to the same cultural-political space, Central Europe, with a strong, continental

orientation and a centuries-long experience and tradition of German cultural,

economic, and political influence, but also dominance [

Jordan 2005].

Besides the two more or less uniting criteria, the third selection criterion was a

dividing factor: Germany and Austria are members in the European Union (EU), whereas

Switzerland is only indirectly involved in European integration through its

membership in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and a set of bilateral

agreements with the EU. Switzerland is also member of the Schengen area allowing any

person, irrespective of nationality, to cross the internal borders without being

subjected to border checks. Currently, most of the EU countries plus the non-EU

countries Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein have joined the Schengen

area. Against this background I expect these three countries to form an “imagined

community” (Benedict Anderson) and to share certain values, interests and world

views reflected by the New Year’s addresses. Further, I expect German and Austrian

New Year’s speeches to share discursive patterns related to EU affairs, especially to

the euro crisis (since 2008), the conflict in Ukraine (since 2014), and the refugee

crisis (since 2015).

[3] I also could explore the impact of the global Covid-19 pandemic

disease on both the content and vocabulary across the three countries yet this impact

is visible only in the speeches for the year 2021.

New Year’s speeches held by leading politicians–mostly prime ministers or

presidents–have a long and firm tradition in Europe and “have

become an institution instead of being a crowing event for conciliatory

efforts”

[

Portman 2014, 89]. From the perspective of political

communication, New Year’s addresses fulfil a triple function in the intersection of

the past, the present and the future. First, they summarise the past year from the

perspective of the political leadership and, hence, recall, reconstruct and remind

the most important events of the year. Second, New Year’s speeches describe the

present and, thus, can be understood and analysed as reality constructions, as

windows to the current state of affairs. And third, New Year’s speeches serve as road

maps to the future, into the new year. In this sense, a New Year’s speeches

summarises the most important future challenges, expectations and opportunities.

There exist only a small number of dedicated studies on New Year’s speeches [

Heikkinen 2006]

[

Portman 2014]

[

Purhonen and Toikka 2016]. I could not identify any specific reason for this,

despite that New Year’s speeches are dominantly given in non-English speaking

countries in Europe. As a text genre, however, New Year’s addresses are comparable

with the Presidential Inaugural speeches of the U.S. and this article

methodologically benefits from the study of [

Light 2014] on the United

States’ Inaugural Addresses. From the perspective of social sciences I am not

primarily interested in the use of language, but issues mentioned and described in

the addresses. This viewpoint is rooted in the assumption that a political

phenomenon, topic or event gains in importance if mentioned in a New Year’s address.

Here I also follow the idea that New Year’s speeches offer insights into shifts in

political priorities, interests, and opinions [

Light 2014, 117].

Against this background I am convinced that a longitudinal, computational analysis of

German, Austrian and Swiss New Year’s addresses can help us to a better understanding

of how the political landscape has changed between 2000 and 2021, but also where the

differences and similarities can be found between these three countries.

The speech corpus covers a period of 22 years and contains 64 speeches. There are two

missing years – 2002 and 2017 – in the Austrian speech collection. In Austria Federal

President delivers the New Year’s speeches and between 2000 and 2004 the speeches

were delivered by Thomas Klestil, between 2005 and 2016 by Heinz Fischer, and since

2018 by Alexander Van der Bellen. Although speeches from 2005 onwards can be

downloaded from the

official website of

the Austrian Federal President. Fortunately, the speeches of 2000-2001 and 2003-2004

could be found in different Austrian media archives. As regards the year 2002,

neither the President’s office nor the National Archive of Austria could provide any

information about where this particular New Year’s speech could be found, so that I

was forced to drop this year from the corpus. In 2017 Austria had an extraordinary

political situation with no Federal President in office, so that no New Year’s speech

was given.

In Germany, the New Year’s speeches are held by Federal Chancellor and full texts are

available on the

official website.

[4]. The

first six speeches (2000-2005) were held by Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, the

remaining sixteen from 2006 to 2021 by Chancellor Angela Merkel. In Switzerland, the

annual New Year’s speech is delivered by the President of the Confederation and all

speeches since 1980 are available online on the

official website of the President of the Confederation. As the term of the

Swiss President is just one year all New Year’s speeches are held by a different

person (except Micheline Calmy-Rey, Pascal Couchepin and Moritz Leuenberger, all of

them re-elected and with two speeches).

Despite the varieties in the use of language in the German-speaking Europe, formal

speeches by top-level politicians can be seen as an appropriate source of data, as

policy discourses are comprised of policy addresses and speeches about policy issues

[

Van Dijk 1977].

New Year’s speeches are traditionally broadcasted over TV or radio within a

relatively short time of 10 to 15 minutes. Consequently, these speeches are relative

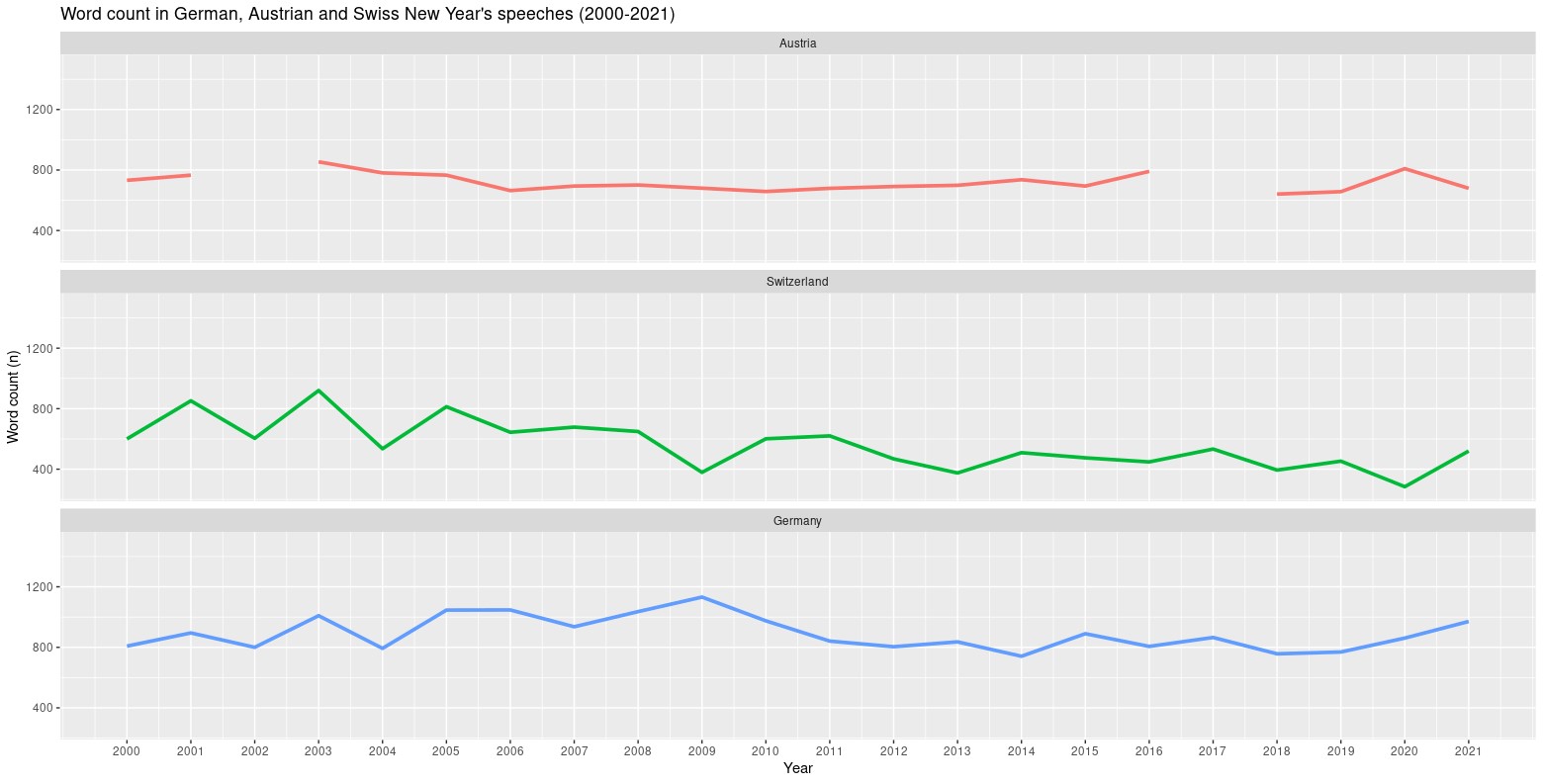

compact in size. The average speeches length of a German new New Year’s speech was

892 tokens and standard deviation (sd) was 111. In Austria and Switzerland the

average lengths were 719 (sd=58) and 562 (sd=159) respectively (Figure 1). Quite

understandably the amount of unique tokens is somewhat lower, since certain words are

used several times during a speech. For German New Year’s addresses, there were 362

unique tokens in average (sd=33), for Austrian and Swiss speeches the average number

of unique tokens was 317 (sd=27) and 255 (sd=60) respectively. Swiss New Year’s

speeches seem to have become shorter over time, whereas both German and Austrian New

Year’s speeches remain relative stable over time (Figure 1). Generally speaking a

country’s size seem to matter here, as German New Year’s speeches are slightly longer

than the Austrian or Swiss addresses. My explanation for this observed difference

stems from the differences in political and economic importance. Germany’s central

role in European politics results in broader political agenda, so that there are more

issues and topics to be addressed to in a New Year’s address.

As regards the analysis workflow, all collected speeches were saved in separate files

in plain text format. These files were then imported into

RStudio, a graphical end-user environment

for the statistical

package R. The

research data was created and analysed in the four steps. First, I used the package

’udpipe’

[5] to tokenise,

part-of-speech tag, and lemmatise the documents. After this step, the data was

structured as a data table consisting of 53893 words and 5277 unique lemmata,

enriched with descriptive metadata about the country and the year, as well sentence

indices. In the third step, I used text mining and explorative data analysis tools

from the package

’tidytext’ to carry out different text analyses and to transform textual

data to different sets of text network data. The applied text mining methods will be

described in the next section. For the text network network creation I used both

bi-grams by linking two consecutive words, as well skipgrams of length two by

combining non-adjacent words that were three, four or five words apart.

[6] Both the bi-grams and

skipgrams were created within the boundaries of the same sentence based on the

sentence index included in the data structure. (2) in the case of concepts used in a

single country, only concepts which occur more than three times are included. Text

networks were visualised and analysed with ’visone’, a fully-fledged, platform

independent software offering powerful layouts for network visualisations and a

comprehensive set of tools for network manipulation,

transformation and analysis.

4 Results

Figure 2 presents the addresses network for the whole corpus based on the similarity

of the New Year’s addresses. Similarity is here calculated as cosine measure, a

term-based comparison between documents in a document corpus, and has a value range

from 0 (no similarity at all) to 1 (full similarity).

[7] I reduced noise in the document-term matrix

by removing both stopwords and all terms except nouns, verbs, pronouns, and proper

nouns. In the network visualisation nodes represent different New Years speeches and

are coloured with country-specific colours so that German addresses are coloured with

yellow, Austrian with red, and Swiss speeches with white. I have also added labels to

help the reader to identify different addresses. Nodes are connected by edges, of

which width is visualised proportional to the cosine measure of the two speeches

connected by that edge. In my data the cosine measures ranged from 0.103 (between the

Swiss speeches 2006 and 2020) to 0.641 (between the German speeches 2009 and 2010),

but I have removed edges with cosine measure below 0.400 in order to improve the

readability of the network visualisation. Further, I used a force-directed layout and

optimised it to position speeches with higher similarity closer, those with lesser to

each other so that the clusters of more similar speeches are easier to identify.

As regards the similarity network two observations seem appropriate. First, the New

Year’s speeches evidence a stronger similarity within, and weaker similarity across

countries. This is clearly visible in the network structure as well, as speeches from

different countries form clear and distinct cluster in the visualisation (see Figure

2). Overall, the average similarity for cross-country speeches is 0.318 (min=0.114,

max=0.514), for national speeches the average similarity is 0.384 (min=0.103,

max=0.614). If we set the threshold value for cosine measure to 0.5, only two

cross-national combinations, namely Austria 2018 – Switzerland 2020 (0.505) and

Germany 2014 – Switzerland 2018 (0.514), exceed this limit. Varieties of national

political agenda and circumstances seem to explain these observed differences, thus

underlining the primacy of national topical issues. An interesting result is also

that the cosine similarity between German and Austrian speeches is significantly

higher (mean=0.355) than that between German/Austrian and Swiss speeches

(mean=0.277). This difference is at least partly explained by the EU membership, as

certain topical issues both German and Austrian speeches tackle are connected to EU

politics.

And second, similarity seems to be stronger between between chronologically close

speeches and weaker between speeches with greater temporal distance. I tested this

with a simple Pearson’s correlation test and calculated the correlation between the

cosine measure and the temporal distance in years between the New Year’s addresses.

The correlation was -0.085 (p<0.001), thus confirming the hypothesis that the

similarity measure decreases when the temporal distance between compared speeches

increases. This seems logical when reflected against the fact that New Year’s

speeches tackle topical issues at the end of a year. The longer the temporal distance

between two addresses, the more probable there has been significant changes in

political circumstances affecting the vocabulary used in the addresses. Hence, this

observation also gives support to the argument that New Year’s speeches offer an

interesting and valuable perspective on a year’s prevailing political reality.

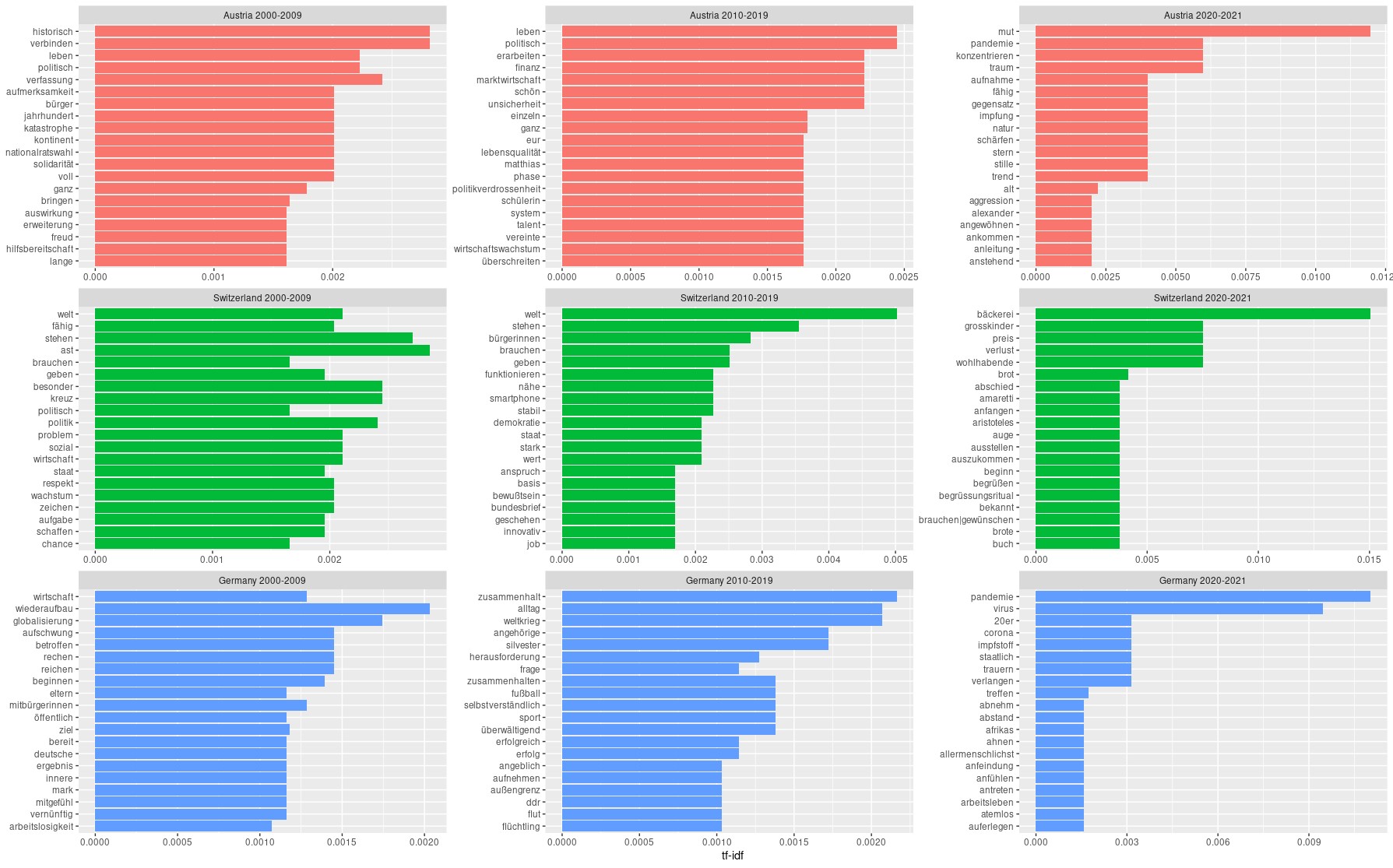

Results from the document-level TNA suggested the existence of variance in vocabulary

between the countries and over time. In order to better understand this variance I

applied a specific text mining method, called term frequency, inverse document

frequency (tf-idf) analysis, to adjust the frequency of a word for how

rarely it is used in the collection of New Year’s speeches of each country. A word’s

inverse document frequency (idf) was then applied to explore words that

are not used very much during the whole period from 2000 to 2021. I divided each

national collection of New Year’s speeches into three distinct periods of 2000-2009,

2010-2019, and 2020-2021. Here the idea was to capture changes in the vocabulary over

time within a country, most probably caused by changes in topical issues or political

circumstances. The results of this tf-idf analysis are presented in

Figure 3. In this barplot we can see for each country the most important words in

each distinct period of time. Hence, the Figure 3 highlights temporal changes within

each country, but preserves national differences. In my opinion three central

findings from this analysis are worth being discussed in detail.

First, the connection to topical political issues and circumstances is especially

evident in Germany across the time periods, but also clearly visible in Austrian

speeches of the last two periods. As regards Germany, during the first period

(2000-2009) words like “wiederaufbau” (rebuilding), “betroffen” (upset),

and mitgefühl“” (sympathy, compassion), together with such words like

“naturkatastrophe” (natural disaster), “region” (region), or

“erschüttern” (shock, shake) belonging to the top-30 tf-idf

words in this period, tackle the 2002 European flood. Germany was the hardest hit

country in Europe and the flood resulted in heated political discussions in the eve

of the Federal elections 2002. In Austrian speeches of this period words like

“jahrhudert” (century), “katastrophe” (catastrophe), and

“hilfsbereitschaft” (helpfulness) document the presence of the 2002 flood –

which hit also Austria quite severely – also in Austrian political discourses.

Another issue in this period was the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in the

eurozone in 2008/2009. This economic crisis is present in German speeches through

words like “globalisierung” (globalisation), “wirtschaft” (economy),

“arbeitslosigkeit”, (unemployment). Contrary to Germany, the eurozone crisis

is not very present and visible in Austrian speeches in this period of time. A

possible explanation to this difference might be found in the different roles the two

countries played in the early stage of the eurozone crisis. Germany as the strongest

economy in the eurozone played a central, designing role from the very beginning of

the eurozone crisis [

Müller-Brandeck-Bocquet 2010]

[

Jsnning and Möller 2016]

[

Kundnani 2016]

[

Bulmer 2018], whereas Austria were not strongly hit by, nor a central

player in this crisis. In addition to that I would also stress the economy-oriented

political culture in Germany. The strong role of economic questions as a central

shaping factor of German domestic and European politics increases the weight of

topical economic issues in public debates. Against this background it is not

surprisingly that the eurozone crisis occupied a more significant space in public

debates in German compared to Austria [

Allen 2005]

[

Maull 2018].

During the second period (2010-2019) the focus of German New Year’s speeches shifts

from economy to refugee politics. In 2015 Chancellor Merkel decided to keep German

state borders open to refugees coming mainly from the Middle East. Although this

political turn was captured in positive political slogans like

“Willkommenskultur” (culture of welcoming) or – most prominently – “Wir

schaffen das” (we can do it/ we manage it), the fact that words like

“flüchtling” (refugee), “zusammenhalt” (sticking together),

“herausforderung” (challenge), “außengrenze” (outer border), or

“aufnehmen” (receive, welcome) are among the top-20 terms underline the

change the refugee crisis caused in German public and political discourses during

this period of 2010-2019. From the methodological point of view the identification of

terms with a clear connection to the refugee crisis evidence the usefulness of

tf-idf analysis when it comes to explore discursive changes. Contrary

to Germany, the refugee crisis was not central in Austrian New Year’s addresses.

Instead, the national political and economic setting seem to dominate Austrian

addresses. Terms like “marktwirtschaft” (market economy), “lebensqualität”

(quality of life), or “finanz”(finance) tackle economic consequences of the

eurozone crisis. The word “politikverdrossenheit” (jadedness with politics)

refers to domestic political turbulences behind the rise of the right-wing populist

Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) in the mid-2010s. Although this rise was partly

supported by the refugee crisis, it was also an expression of disillusionment with

the political elite.

Second, as expected the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic disease in Europe in the

first half of 2020 resulted in a clear change, especially as regards the German and

Austrian New Year’s addresses. Words like “pandemie” (pandemic),

“impfung”/“impfstoff” (vaccination), “abstand” (distance), or

“corona” (coronavirus) poke from the results as indicators for this

discursive change in political and public discourse in Germany and Austria. Once

again, the results also confirm the usefulness of tf-idf analysis for

the exploration of discursive changes through changes in vocabulary over time.

And third, the overall results confirm the hypothesis that Germany and Austria are,

what comes to political agenda and circumstances, as well to topical issues, closer

to each other than to Switzerland. It is, however, a somewhat odd observation that

Swiss speeches seem to avoid topical political issues and to concentrate

on the construction of neutral narratives. A possible explanation for this might be

found in the fact that in Switzerland, as opposed to Germany and Austria, the federal

president giving the New Year’s speech is not the head of state, but just the head of

Switzerland’s Federal Council, and only carries out some representative duties.

Hence, the federal president is merely a mediator between the different parts of the

Swiss federal state.

The results presented thus far indicate two main aspects. First, New Year’s addresses

offer a valuable and reliable source to explore topical issues and tackle changes in

political and public discourses. And second, although the national political agenda

and circumstances seem to have a stronger impact on the content of the addresses,

significant European political incidents and events, e.g. the refugee crisis or the

Covid-19 pandemic disease, seem to cause changes across countries. This leads us to

the final analysis, an attempt to explore shared topics. For this analysis I

constructed text networks based on bigrams, i.e. word co-occurrences of two adjacent

words, and of skipgrams, i.e. combinations of two non-adjancent words that are three

to five words apart [

Jelveh et al. 2014, 1805]. The bi- and skipgrams

were created for words occurring within the same paragraph. Since the idea is to

analyse topics across countries all word pairs co-occurring in New Year’s speeches of

one single country only were removed. In the last step I calculated a co-occurrence

weight measure by dividing the number of speeches a word pair co-occurs by the total

number of speeches (64) in the multi-national corpus. The interpretation of this

weight measure is rather straightforward: the higher the value, the more significant

the word pair for the cross-country content.

Figure 4 visualises word co-occurrences network across countries based on bigrams,

whereas Figure5 visualises word co-occurrence network across countries based on

skipgrams. Hence, both visualised text networks present shared word co-occurrences

central for the multi-country corpus of German, Austrian, and Swiss New Year’s

addresses, i.e. word pairs that can be interpreted as fundamental for the – put in

Benedict Anderson’s (1991) famous terminology – imagined discursive community of

these three German-speaking countries. The bigram-based core text network consists of

336 words and 565 co-occurrences, whereas the skipgram-based core text network

consists of 423 words and 1157 co-occurrences.

In order to visually highlight the most important structural properties both

visualisations apply identical visualisation effects:

- Node size is mapped to the node’s degree centrality value and node label size

is mapped the nodes betweenness centrality measure. In network theory centrality,

in general, indicates a node’s position in the network and can be calculated

either relative to a node’s direct neighbours or the whole network. A node’s

degree is the simplest centrality measure and equals to the number of connections

the node has to other nodes. Betweenness, as the term itself indicates, defines

centrality by analysing where a node is placed within the network. Consequently, a

node’s betweenness centrality score is computed by taking into consideration the

rest of the network and by looking at how many times a node sits on the shortest

path linking two other nodes together, thus helping to identify nodes having

“a high probability of occurring on a randomly chosen

shortest path between two randomly chosen vertices”

[Hasu and Kao 2013]

[Prell 2012, 103–104]. Considering meaning circulation across

the entire network, the latter capability is assumed to be more relevant, since

betweenness centrality “shows the variety of contexts where

the word appears, while high degree shows the variety of words next to which

the word appears”

[Paranyushkin 2011, 13]. This difference is important to keep

in mind and therefore I use betweenness centrality to measure a concept’s general

status in the text network. As both [Paranyushkin 2011] and [Shim et al. 2015] point out concepts with high betweenness and degree

centrality play a meaning circulation role across texts in the document corpus,

whereas concepts with low centrality measures are peripheral concepts and, thus,

typical only for a certain part of documents. Between these two extremes are

located concepts with high betweenness but low degree centrality and concepts with

low betweenness but high degree centrality. The former play an important role as

bridging concepts between local communities, the latter, in turn, are local hubs

within a cluster [Shim et al. 2015, 59f]. This mapping strategy allows

us to easily identify the most important and influential words in the

graph.

- Node colour is mapped to the topic cluster the node belongs to. One of the

proposed key advantages of TNA is bound with the possibility to exploit network

community detection techniques.[8] The underlying idea here is that when textual

documents are reconstructed as text networks a word’s position in the network is

not random but determined relative to the context it appears in. Consequently,

words belonging to the same (or similar) context are assumed to cluster across

documents, so that we could be able to identify groups of words in the network

structure having dense connections within the group, but sparse

connections to other parts of the text next. These groups are here interpreted as

topics describing the main thematic content of the document corpus. By leaning on

the promising results of [Paranyushkin 2011] and [Shim et al. 2015] I applied a modularity-based community detection method

called “Louvain method” based on the assumption, that nodes

being more densely connected together than with the rest of the network construct

a network community [Blondel et al. 2008]. The method identified in total

13 clusters - in my interpretation: topics - in the bigram-based and 12 topics in

the skipgram-based text network.

- Edge width is mapped to the weight of the co-occurrence of the word pair. The

more often two words co-occur in the document corpus, the wider the connecting

edge is visualised in the network graph. Since the graph includes only word pairs

shared by at least two countries, edge effects help us to identify word pairs used

together frequently across countries.

- Layout used for the visualisation is a radar-like centrality layout, in which a

node’s position is determined by its topic cluster and links are arranged

according to their weights. The underlying idea of this layout is to gather nodes

belonging to the same cluster on the same circumference. Further, the

visualisation makes also connections between the clusters – i.e. word pairs, of

which words belong to different topic clusters – easier to identify. As regards

the meaning circulation across the multi-country text network word pairs

connecting two topics can be analysed from the perspective of structural holes.

These connections bridging two separate topics by closing a structural hole in a

network can make us aware of possibly existing latent similarities between these

two topics [Burt 2004].

| Bigram text network core communities |

(Total # of clusters: 13, modularity: 0.55) |

|

Cluster

|

Core content words of the topic(a) |

|

#1: Solidarity / Sense of community (55 words in total) |

bürgerin/bürger, frieden, geschichte, hilfbereitschaft, sicherheit,

stabilität, verantwortung, wiederaufbau, zukunft, zusammenhalt |

|

#2: Crisis recovery (41) |

einsetzen, ereignis, erinnern, freuen, generation, glauben, krise,

verbinden, weltkrieg, überwinden |

|

#3: Covid-19 era (36) |

erfolgreich, familie, friedlich, meistern, pandemie, phase, resignation,

schwierig, zeit, zusammenleben |

|

#4: Europe (32) |

entwicklung, erweiterung, europäisch, hoffnung, krieg, mitgliedstaat,

parlament, terror, union, wählen |

| Skipgram text network core communities |

(Total # of clusters: 12, modularity: 0.35) |

|

Cluster

|

Core content words of the topic(a) |

|

#1: Crisis recovery (62 words in total) |

erinnerung, friedlich, krieg, mauer, notwendig, optimismus, pandemie,

vergessen, verlust, wirtschaftskrise |

|

#2: Faith in the future (51) |

aufschwung, bemühen, gestaltung, neugier, selbstvertrauen, technik,

wirklichkeit, wissenschaft, zufriedenheit, zuversicht |

|

#3: Economy (46) |

arbeitsplatz, beitrag, einsatz, erreichen, global, idee, leisten, offen,

unternehmen, wirtschaft |

|

#4: Solidarity / Sense of community (45) |

alltag, bürgerin/bürger, demokratie, entwicklung, familie, frieden,

gemeinsam, gemeinschaft, stehen, welt |

Table 1.

Most important topics in the New Year’s speeches across countries.

(a) Core content words include ten (10) most influental words relative to the topic

of the cluster (listed in alphabetical order). Bold words indicate top ranking words

both in degree and betweenness centrality, i.e. words being central for meaning

circulation across the text network.

Table 1 summarises the most significant results of the community detection analysis

of both the bigram based and the skipgram based text network by focusing on the four

largest communities found by the Louvain algorithm. As expected there is some

variance across topics between the bigram and skipgram networks. I consider this

variation as normal when the differences in network data creation is taken into

account. Actually, against this background, the two networks should not be considered

as exclusionary but complementary to each other. I have given each community a

descriptive label based on a manual evaluation of the vocabulary linked to the

community.

There are two shared topics. I have labelled the first “Solidarity / Sense of

community” and it is the largest topic in the bigram and fourth largest topic

in the skipgram text network. Both includes words “bürger/bürgerin” (citizen)

and “frieden” (peace). In the bigram network this topic is with respect to

content more focused on helpfulness and security, indicated through words like

“hilfebereitschaft” (helpfulness), “sicherheit” (security),

“stabilität” (stability), “verantwortung” (responsibility), and

“zusammenhalt” (togetherness, solidarity). The skipgram network, in turn, has

in this topic a stronger bias towards democracy and society embodied by words like

“alltag” (everyday life), “demokratie” (democracy), “familie”

(family), and “gemeinschaft” (community).

This topic appears in different contexts over time. In the German New Year’s speech

in 2006 the topic is used to emphasise the inter-linkages between Germany and the

international, global community:

[9]

Deutschland ist keine Insel. Wir stehen

in einem internationalen Qualitätswettbewerb, der alle Bereiche unseres

Zusammenlebens betrifft: Welcher Nation gelingt es am besten, die

schöpferischen Kräfte ihrer Menschen zu wecken? Wie offen ist eine Gesellschaft

für Neues? Was bietet sie jungen Familien? In welchem Land gibt es die besten

Schulen und Hochschulen? Wie gut gelingt das Miteinander von Einheimischen und

Zuwanderern?

(Germany 2006)

In the German speech of 2015, the topic is used in the context of the refugee crisis

to foster solidarity among citizens, but also to strengthen confidence and commitment

to the community and its values:

Genauso klar ist: Nur mit offenen

Diskussionen und Debatten können wir Lösungen finden, die langfristig Bestand

haben und von Mehrheiten getragen werden. Wir sind es, die Bürger und ihre

gewählten Repräsentanten, die entwickeln und verteidigen werden, was dieses

unser liberales und demokratisches Land so lebenswert und liebenswert macht.

Wir sind es, die Lösungen finden werden, die unseren ethischen Normen

entsprechen, und den sozialen Zusammenhalt nicht gefährden. Lösungen, die das

Wohlergehen der eigenen Bürger berücksichtigen, aber nicht die Not der

Flüchtlinge vergessen.

(Germany 2015)

The Austrian speech of 2007, in turn, highlights the role of persons in different

positions of trust for the security, stability and confidence of the community:

Lassen Sie mich abschließend die

Gelegenheit benutzen, um den vielen Frauen und Männern herzlich zu danken, die

in den verschiedensten Funktionen für unser Gemeinwohl, für unsere Sicherheit,

für unsere Gesundheit und für den Zusammenhalt unserer Gesellschaft

buchstäblich oft Tag und Nacht beruflich, oder auch als freiwillige Helferinnen

und Helfer tätig sind. Der Wert dessen, was hier geleistet wird, kann gar nicht

hoch genug eingeschätzt werden.

(Austria 2007)

And finally, the following two quotes from the Swiss speeches of 2017 and 2021

establish connections between the economic welfare, sovereignty and stability of the

country and the solidarity and togetherness of the society:

Stabil und erfolgreich wollen wir auch

in Zukunft sein. Dazu braucht es mehr denn je den Zusammenhalt. Unsere

Gesellschaft ist stark, weil wir erprobt sind im Versöhnen von

Ansprüchen.

(Switzerland 2017)

Wir Schweizerinnen und Schweizer müssen

zusammenstehen. Nur so können wir als Land einstehen für die Interessen von uns

allen: für unsere Gesundheit und unser wirtschaftliches Wohlergehen, für

Frieden und Verbundenheit, für Freiheit und Unabhängigkeit, – kurz: für alles,

was uns seit Langem lieb und teuer ist.

(Switzerland 2021)

The second shared topic is labelled “Crisis recovery”. The content vocabulary of

this topics indicates that this topic is not limited to the Covid-19 pandemic disease

only. Instead, this topic seems to be used over time to embed a current, topical

crisis into a wider, historical context. Although the clustering algorithm allocates

topical words like “pandemie” (pandemic) or “wirtschaftskrise” (financial

crisis) to this cluster, in my interpretation other content words like

“generation” (generation), “krieg / weltkrieg” (war / world war),

“überwinden” (overcome), “optimismus” (optimism), “mauer” (wall),

and “erinnern” (remember) stand for this wider historical context.

Both in the Swiss speech in 2010 and German speech in 2011 this topic was used to

frame the eurozone crisis. Both quotations manifest a clear optimism that the crisis

has been successfully fought and the country will recover rather quickly:

Wir verfügen über eine starke Wirtschaft

und eine solide Finanzpolitik. Wir haben es geschafft, trotz grosser

Wirtschaftskrise die Schulden nicht übermässig wachsen zu lassen. Das wird uns

im Aufschwung stärken.

(Switzerland 2010)

Deutschland hat die Krise wie kaum ein

anderes Land gemeistert. Was wir uns vorgenommen hatten, das haben wir auch

geschafft: Wir sind sogar gestärkt aus der Krise herausgekommen. Und das ist

vor allem Ihr Verdienst, liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger.

(Germany 2011)

In 2020, the Austrian speech used this topic in a totally different context combining

the most important crises and challenges of the current time, i.e. climate change,

digitalisation, and migration, as well questions related to gender equality and

welfare state reforms.

Zur Klimakrise kommen weitere große

Herausforderungen: Wie werden wir künftig arbeiten? Welche Antworten geben wir

in Österreich auf die Digitalisierung? Wie soll sich unser Wirtschaftsstandort

entwickeln? Wie gehen wir mit Migration um? Und was tun wir, um Frauenrechte zu

stärken? Haben wir ausreichend drüber nachgedacht, das Nötige im

Bildungsbereich anzugehen? Welche Reformen sind im Gesundheits- und

Sozialsystem notwendig, um soziale Sicherheit und sozialen Zusammenhalt für die

Zukunft zu gewährleisten?

(Austria 2020)

Both text networks produce also distinct topics. In the bigram network we can

identify the unique topics labelled by myself “Covid-19 era” and “Europe”,

in the skipgram network such topics include “Faith in the future” and

“Economy”. As regards the bigram-specific topics, “Covid-19 era” not

only embodies the strenuousness of the pandemic disease by content words like

“pandemie” (pandemic), “resignation” (resignation), or the word

combination “schwierig” + “zeit” (hard times), but also seeks to create

hope through words like “erfolgreich” (successful), “familie” (family),

“meistern” (control), “zusammenleben” (life together). The topic

“Europe”, in turn, tackles both current European issues like terrorism

(“terror”), European parliamentary elections (“wählen” (vote),

“parlament” (parliament)) and European integration as a wider context

(“europäisch” + “union” (EU), “erweiterung” (enlargement),

“mitgliedstaat” (member state)). This latter topic clearly evidences the role

and status of the EU as the most important political, economic, and geographical

context.

The topic “Covid-19 era” is a mixture of resignation and hope. The Austrian

speech in 2021 well exemplifies this mixture:

Ein neues Jahr liegt vor uns. Wir spüren

noch die Last des alten, die Last der Pandemie. Aber viele von uns spüren trotz

allem eine hoffnungsfrohe Erwartung, wie sie nur am Beginn von etwas Neuem

stehen kann, wenn alle Möglichkeiten offen und alle Träume noch frisch

sind.

(Austria 2021)

The German address, in turn, acknowledges the dramatic changes caused by the Covid-19

pandemic disease. At the same, however, the quotation has a positive trait, stressing

the supportive and stabilising role of the federal state in the times of crisis:

Die Aufgaben, vor die die Pandemie uns

stellt, bleiben gewaltig. Bei vielen Gewerbetreibenden, Arbeitnehmern,

Solo-Selbstständigen und Künstlern herrschen Unsicherheit, ja Existenzangst.

Die Bundesregierung hat sie in dieser ganz unverschuldeten Notlage nicht allein

gelassen. Staatliche Unterstützung in nie dagewesener Höhe hilft. Verbesserte

Kurzarbeitsregeln greifen. Arbeitsplätze können so bewahrt

werden.

(Germany 2021)

Contrary to Austria and Germany, the Swiss speech of 2021 is marked by negative

ambience, even resignation underlining the deep societal impact the Covid-19 pandemic

disease has caused in Switzerland:

Selten haben wir Vergleichbares erlebt:

Unsere Tätigkeiten kamen zum Stillstand. Die ganze Gesellschaft befand sich in

noch nie dagewesener Isolation. Wir mussten lernen, ohne Händeschütteln

auszukommen. Dieses wichtige Begrüssungsritual gefährdete plötzlich unsere

Gesundheit.

(Switzerland 2021)

The topic “Europe” is mostly used, as the following quotations exemplify, to

remind the citizens about the fundamental importance of European integration as a

uniting community of Europeans, but also as provider for economic and political

security in a global world:

Es geht nun darum, dass die Union nicht

nur wirtschaftlich, sondern auch verstärkt politisch und emotional

zusammenwächst. Die Bürger müssen spüren, dass es sich lohnt, in diesem

erweiterten Europa zu leben und zu arbeiten.

(Austria 2003)

In den vergangenen Jahren habe ich oft

gesagt, dass es auch Deutschland auf Dauer nur dann gut geht, wenn es auch

Europa gut geht. Denn nur in der Gemeinschaft der Europäischen Union können wir

unsere Werte und Interessen behaupten und Frieden, Freiheit und Wohlstand

sichern.

(Germany 2020)

Wirtschaftlich sind wir weltweit

verflochten. Geografisch, historisch und kulturell sind wir ein europäisches

Land. Die Beziehungen zu unseren Nachbarländern und zu den anderen

Mitgliedstaaten der Europäischen Union regeln wir in bewährter Weise bilateral.

(Switzerland 2005)

Within the skipgram network, the topic “Faith in the future” represents a strong

faith in technological and scientific development as the most important fundament for

a better future. This is especially evident when we consider such content words like

“technik” (technology), “wissenschaft” (science), “aufschwung”

(boom, economic expansion), “selbstvertrauen” (self-confidence), and

“zuversicht” (confidence). Interestingly, this topic also contains words with

strong, dynamic connotation to the shaping the future (“gestaltung”) and the

putting oneself out (“bemühen”). How this topic is used to generate optimism

towards the future is well illustrated by the following quotations:

Wie wichtig es ist, auch im scheinbar

größten Durcheinander Gelassenheit, Mut und Zuversicht zu bewahren.

(Austria 2020)

Zusammenhalt, Offenheit, unsere

Demokratie und eine starke Wirtschaft, die dem Wohl aller dient: Das ist es,

was mich für unsere Zukunft hier in Deutschland auch am Ende eines schweren

Jahres zuversichtlich sein lässt.

(Germany 2017)

Dennoch bin ich zuversichtlich. Denn ich

glaube an die Fähigkeit des Menschen zu gestalten. Es gibt immer einen Weg.

Manchmal braucht es Mut und Kraft.

(Switzerland 2010)

Finally, the topic “Economy” is characterised by very concrete, economic content

words like “arbeitsplatz” (job, post), “global” (global[isation]),

“unternehmen” (company), and “wirtschaft” (economy). But this topic also

has a forward-looking content embodied by words like “erreichen” (reach),

“idee” (idea), or “leisten” (perform). An excellent example of how this

topic is present in the speeches is the following quotation from the German speech of

2008: “Deutschland kann seine alte Kraft als das Land der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft

wieder neu unter Beweis stellen, der Verbindung von Freiheit und Gerechtigkeit,

Fleiß und Unternehmergeist”. The same spirit can be found in the following

Austrian and Swiss addresses:

Unsere Bevölkerung hat nicht nur ein

Recht auf sichere Grenzen und innere Sicherheit, sie hat auch ein Recht auf ein

möglichst hohes Maß an wirtschaftlicher Stabilität und sozialer

Sicherheit.

(Austria 2013)

Starke Unternehmen sind der beste Garant

für Arbeitsplätze. Und Arbeitsplätze sind die Basis für soziale Sicherheit und

Wohlstand. Noch gehört die Schweiz zu den wirtschaftlich erfolgreichsten

Ländern. Sorgen wir mit freiheitlichen Rahmenbedingungen dafür, dass das so

bleibt.

(Switzerland 2016)

Overall, the topics identified by the Louvain method seem appropriate and reliable in

the context of these three countries. The main topics discussed above not only

connect well to the political and economic reality in these countries or in Europe in

more general terms, but also evidence that TNA tools offer – as the previous studies

of [

Paranyushkin 2011], [

Light 2014], or [

Shim et al. 2015] already suggest – a reliable alternative to traditional

methods of text mining. Further, the differences between topics identified in the

bigram and the skipgram based network seem to give support to the study of [

Jelveh et al. 2014] that the complementary use of both methods can help us to

reliably identify topics that use similar vocabulary but show differences in the text

structure. And finally, it is worth being noted that the most important content words

of each topic contain only a few words with both a high degree centrality and a high

betweenness centrality. This means that the most important content words are those

enjoying higher relevance within the topic and, thus, are descriptive for the topic.

A closer look at words used for meaning circulation across topics and countries

reveals that these words include words related to peace (“frieden”,

“friedlich”) and war (“krieg”), security (“sicherheit”), crisis

(“krise”), community (“gemeinschaft”), economy (“wirtschaft”), and

future (“zukunft”). All these “glueing” words are less topical and more

contextual, thus framing and embedding the topical issues into a wider context of

European (integration) history.