DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly

2021

Volume 15 Number 3

Volume 15 Number 3

Translation Alignment for Historical Language Learning: a Case Study

Abstract

This paper proposes text alignment in digital environments as a way to empower language learning. It presents the principles and goals of text alignment in Natural Language Processing, and introduces Ugarit, a web-based translation alignment editor for the collection of aligned language pairs. Then, it reports observations on the application of translation alignment in historical language courses at Tufts and Furman University between 2017 and 2019.

Introduction

The World Wide Web has introduced a massive change in the cognitive processes of

reading: skimming has become the most popular way in which readers interact with

written texts on digital support, with possible enormous consequences on how

human beings process information and articulate complex thought [Wolf 2018]. On the other hand, digital environments have an

immense, often underdeveloped, potential to improve interactive engagement and

exploration of information, integrating very different media and conveying

extremely complex and multifaceted messages. Readers of the future should be

educated to critically approach a text through digital technologies, making full

use of this potential, and going beyond the reading processes conceived for

texts encoded on static supports. In this paper, we propose the application of

text alignment as one method to empower the reflective engagement with digital

texts, specifically in the context of language learning.

Text alignment, and more specifically translation alignment, is a type of

annotation,[1] which consists in analytically matching a word or expression in a

text with the corresponding ones in another text, often in a different language,

in environments created to collect aligned word pairs. This is an exceptionally

complex hermeneutic task, by which readers are induced to problematize the

function and implications of morphosyntactic, semantic, and expressive devices

of a language, even of their own native tongue.

This paper collects a set of preliminary observations on groups of students that

have used translation alignment in the framework of language courses at various

levels of expertise. We propose text alignment as a way to empower the

perception of the complexity of a written source, but also as a method to

leverage usual obstacles in the process of reading in a different language by

directly engaging with original literary texts.

Principles of Translation Alignment

Translation alignment is one of the most popular applications of Natural Language

Processing. It is defined as the comparison of two or more texts in different

languages, also called parallel texts or parallel corpora [Kay and Röscheisen 1993]

[Véronis 2000],[2]

by means of automated or semi-automated methods. The main purpose is to define

which parts in a source text correspond to which parts of a second text in a

different language. The result often takes the form of a list of pairs of items,

which can be words, sentences, or larger text chunks like paragraphs or

documents. This task is often performed automatically through various methods,

which often require large amounts of training data: one of the most traditional

methods for automated translation alignment is statistical machine translation

[Brown et al. 1990], which uses statistical methods to extract and

identify correspondences of words and phrases in two parallel texts, based on

already available aligned pairs.

The alignment of texts in different languages, however, is an exceptionally

complex task, because of the several variables involved. It is often difficult

to find perfect correspondences across languages that express ideas through

different morphosyntactic constructs, with variations in word order, sentence

length, and even underlying cultural significance. Machine-actionable systems

are often inefficient in providing equivalences for wordplays, metaphors, and

other rhetorical devices. The resulting aligned pairs may be one-to-one (one

word in the source text corresponds to one word in the translation), but often

align as one-to-many, many-to-many, or many-to-one. Each word correspondence may

be complete or perfect (with complete overlap between two words), but also

possible or incomplete (partial overlap, or both words being a translation of

each other only in certain contexts [Graça et al. 2009]).

For these reasons, manually aligned word pairs are one of the main sources of

training data, and are not only employed for the implementation of machine

translation systems, but are increasingly useful for many other purposes,

including information extraction and automated creation of bilingual lexica [Dagan et al. 1999]

[Melamed 1998]. Therefore, large corpora of manually aligned word

pairs are a much desired resource, which remains, however, extremely rare.

The operation of collecting training data is often configured as a Citizen

Science effort: for example, Glosbe (https://glosbe.com/) provides thousands of dictionaries created from

the manual alignment of word pairs performed by a community of users.[3] However, because of the

hermeneutic complexity implied in the alignment across different languages,

translation alignment has also a powerful pedagogical potential. We have

implemented a specific web-based environment, called Ugarit, to provide a

framework for language learning applications through translation alignment.

The Ugarit Translation Alignment Editor

The first public web-based environment for manual text alignment of parallel

corpora was conceived within the Alpheios Project (http://alpheios.net/), and is currently

hosted by the Perseids Project (https://www.perseids.org/). The editor offers an easy environment to

manually match corresponding words in two parallel texts.

The Ugarit Translation Alignment Editor (http://ugarit.ialigner.com/),

developed in 2016 by Tariq Yousef at the University of Leipzig, was conceived as

the first version of an improved interface that could perform more extensive

alignment tasks than the Alpheios editor: it allows alignment in up to three

texts, incorporates transliteration of non-Latin alphabets, and collects

manually aligned pairs as training datasets [Yousef 2019]

[Yousef and Jänicke 2020]. Moreover, it allows almost immediate visible online

publication of the material.

The first version of the tool was made public in March 2017. Since then, Ugarit

has registered an ever-increasing number of visits and new users.

Originally, Ugarit was developed to collect training data for the implementation

of statistical machine translation of historical languages, mainly Ancient

Greek, Latin, and Persian, for which few to none aligned datasets exist.

Ideally, historical languages are closed systems with a finite number of words

and very limited change in the foreseeable future. Therefore, it should be

possible to create adequately efficient automated methods of statistical machine

translation based on a relatively small training dataset.

However, after the tool was made public, the number and variety of languages

included by the users has steadily increased and has gone far beyond the

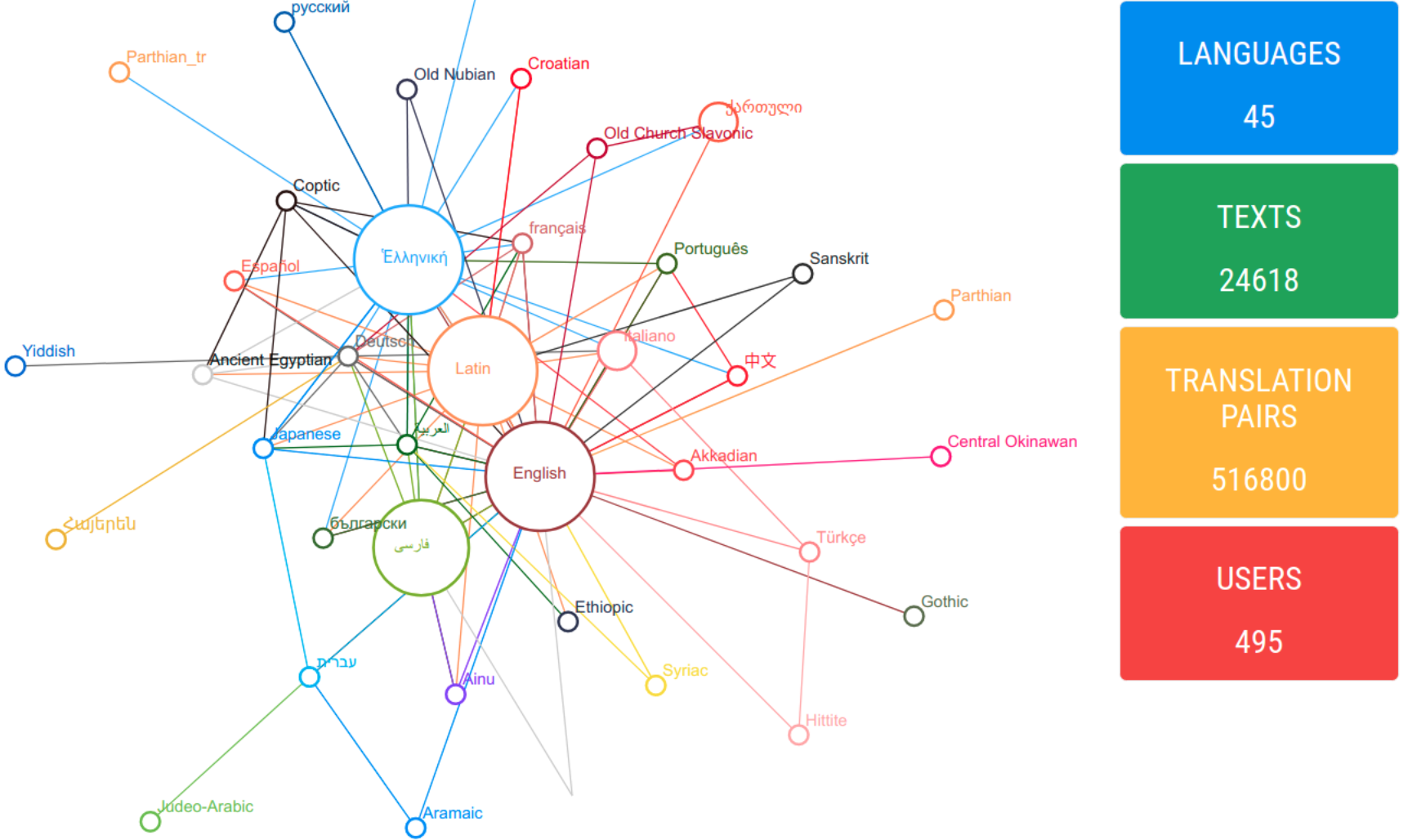

original intent: at the moment this article is being written, 45 languages are

included in Ugarit, including Ancient Greek, Latin, Arabic, Persian, English,

French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Croatian, Armenian, Japanese, Chinese,

Syriac, Sanskrit, Coptic, Egyptian, Akkadian, and Ethiopic; 465 unique users,

and about 24,500 parallel texts, are currently hosted.

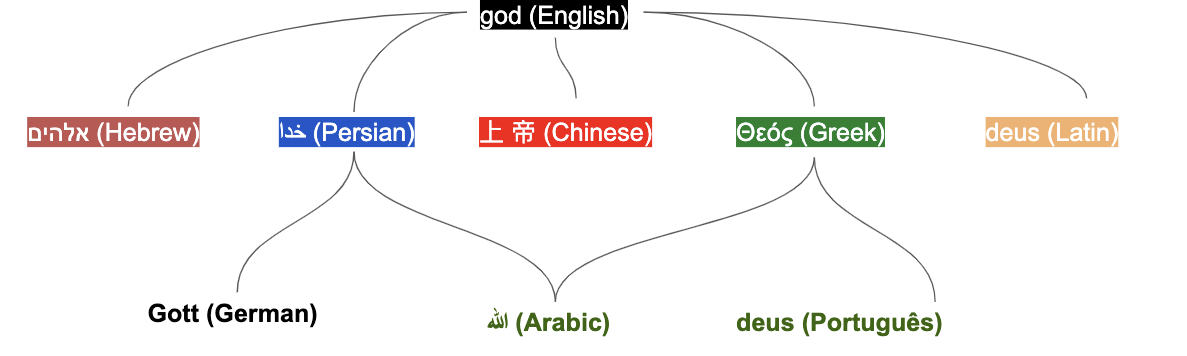

The home page of Ugarit offers a quick overview of the languages currently

available (the graph showing the proportions of the respective corpora), the

number of users and texts, the available word pairs, and the newest

alignments.

The workflow is simple: users can upload their corpus in text format, or import

it by calling its CTS URN from the Perseus Digital Library (http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/) [Babeu 2019].

Then, the parallel texts can be manually aligned by matching words or groups of

words. Resulting pairs are automatically stored in the database, and can then be

exported in XML or tabular format.

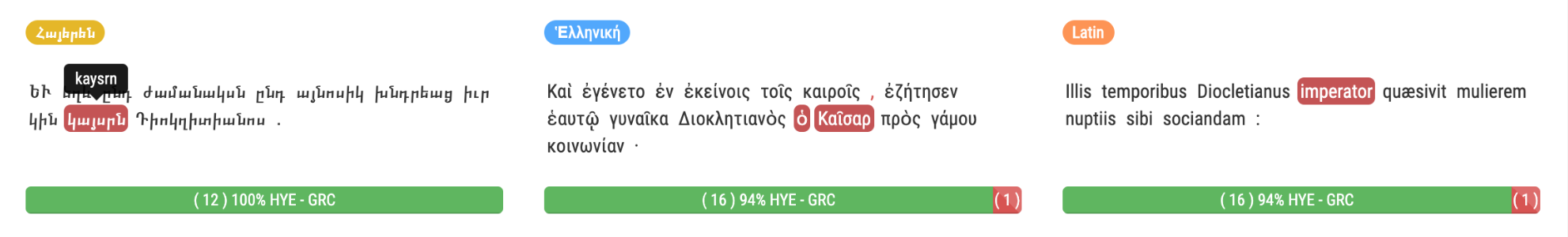

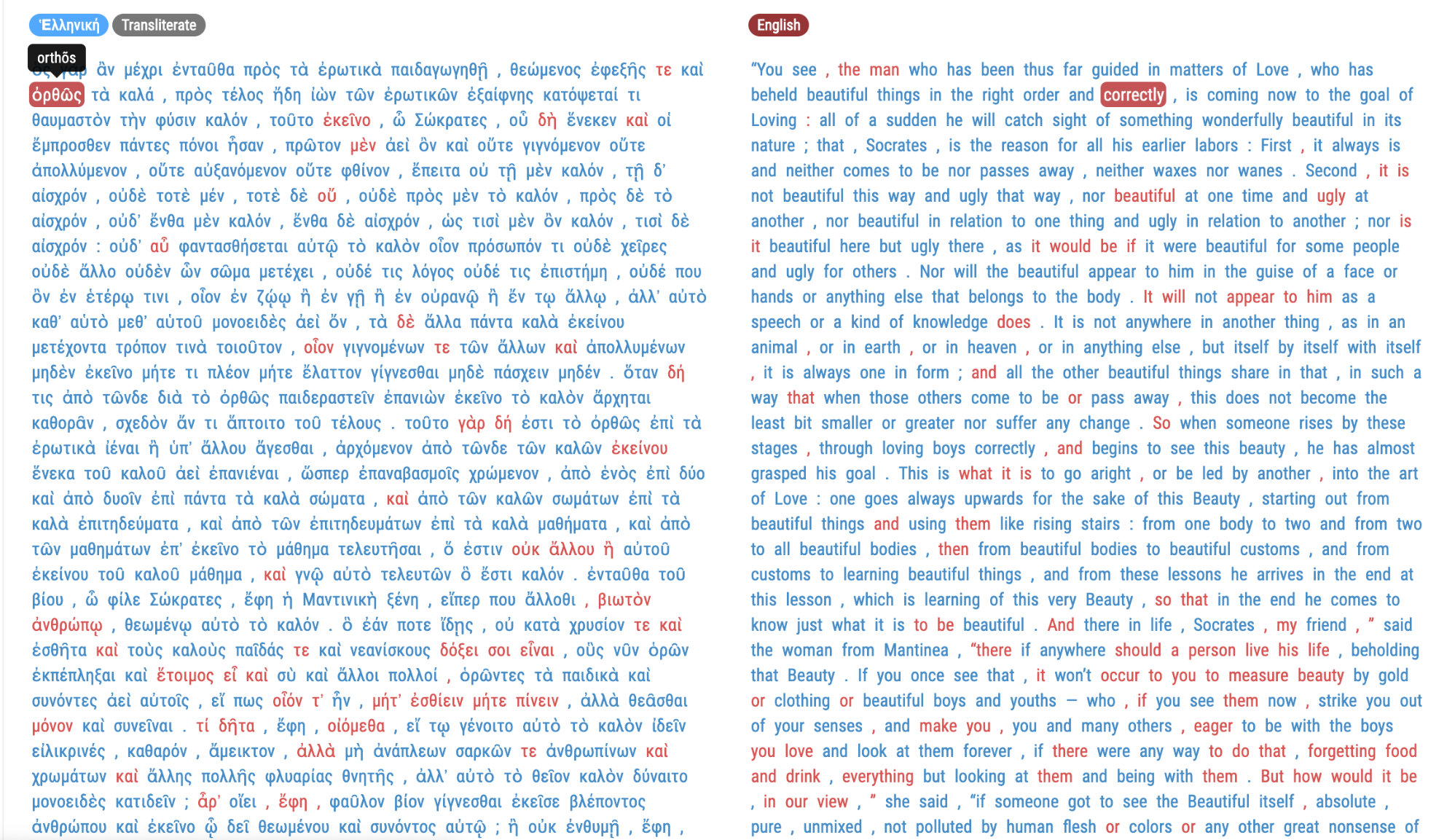

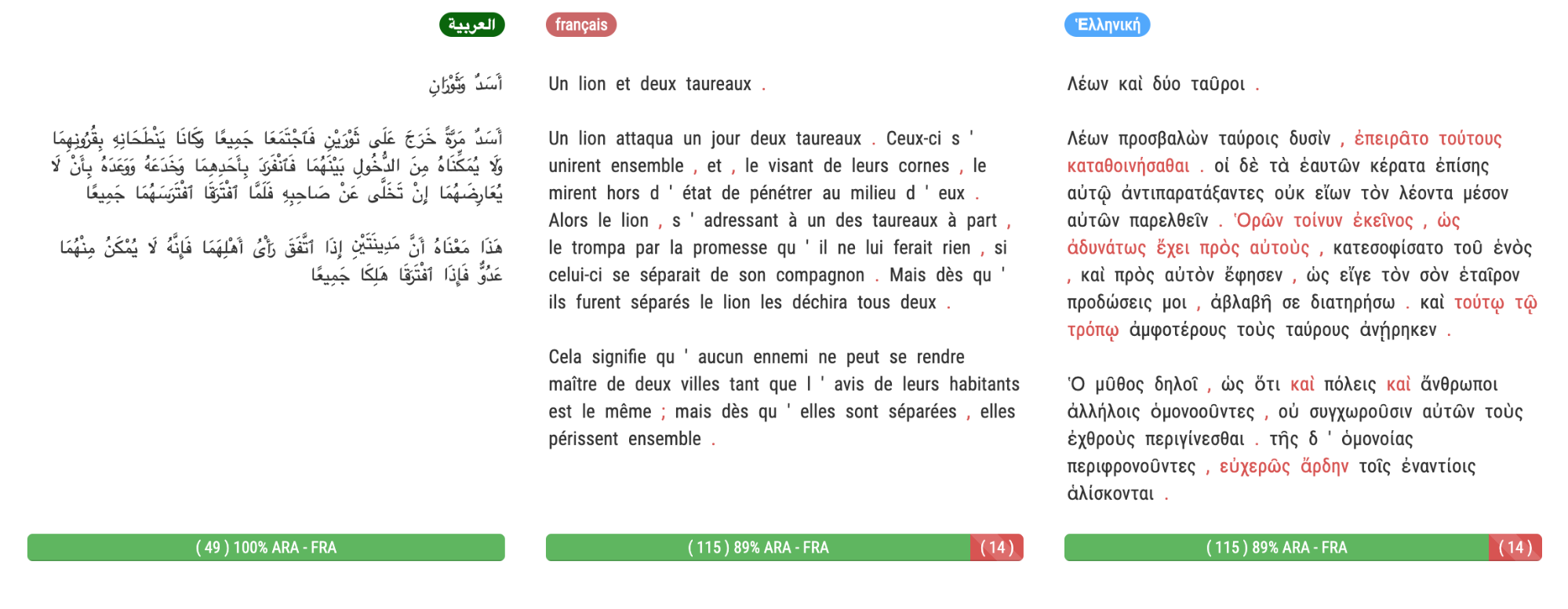

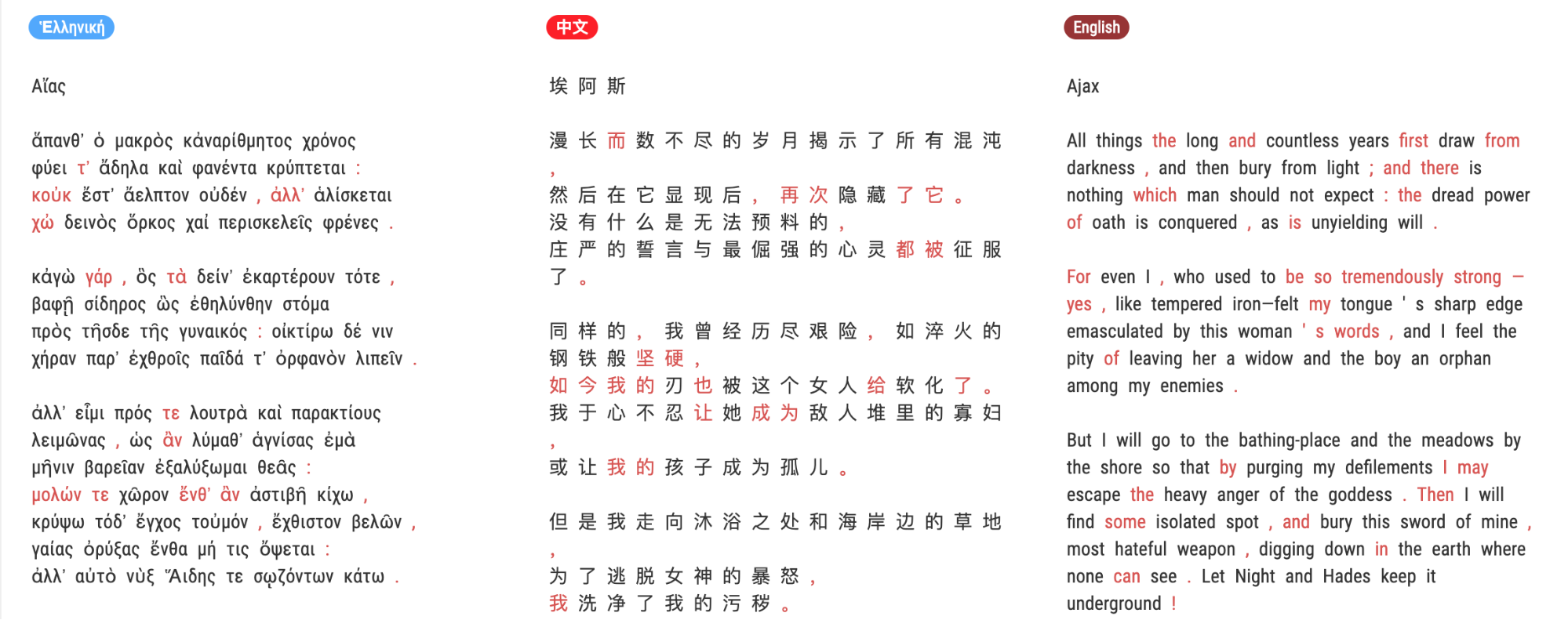

Currently, Ugarit works with up to three texts in different languages, and there

is virtually no limit to the amount and length of texts that can be uploaded. A

clickable option enables the user to decide whether the alignment can be

publicly visible on the website or not. When the default value is kept, the text

appears in the homepage of the website, and other users can inspect the

alignment by hovering with the mouse on individually paired tokens, which are

automatically highlighted. The proportion of aligned tokens is indicated in the

colored bar below the text: the green indicates the rate of matching words, the

red the rate of non-matching words.

For languages with non-Latin alphabets, Ugarit offers automatic transliteration,

which is visible when the pointer hovers on the desired word. This feature is

currently available for Greek, Arabic, Persian,[4] Armenian, and

Georgian.

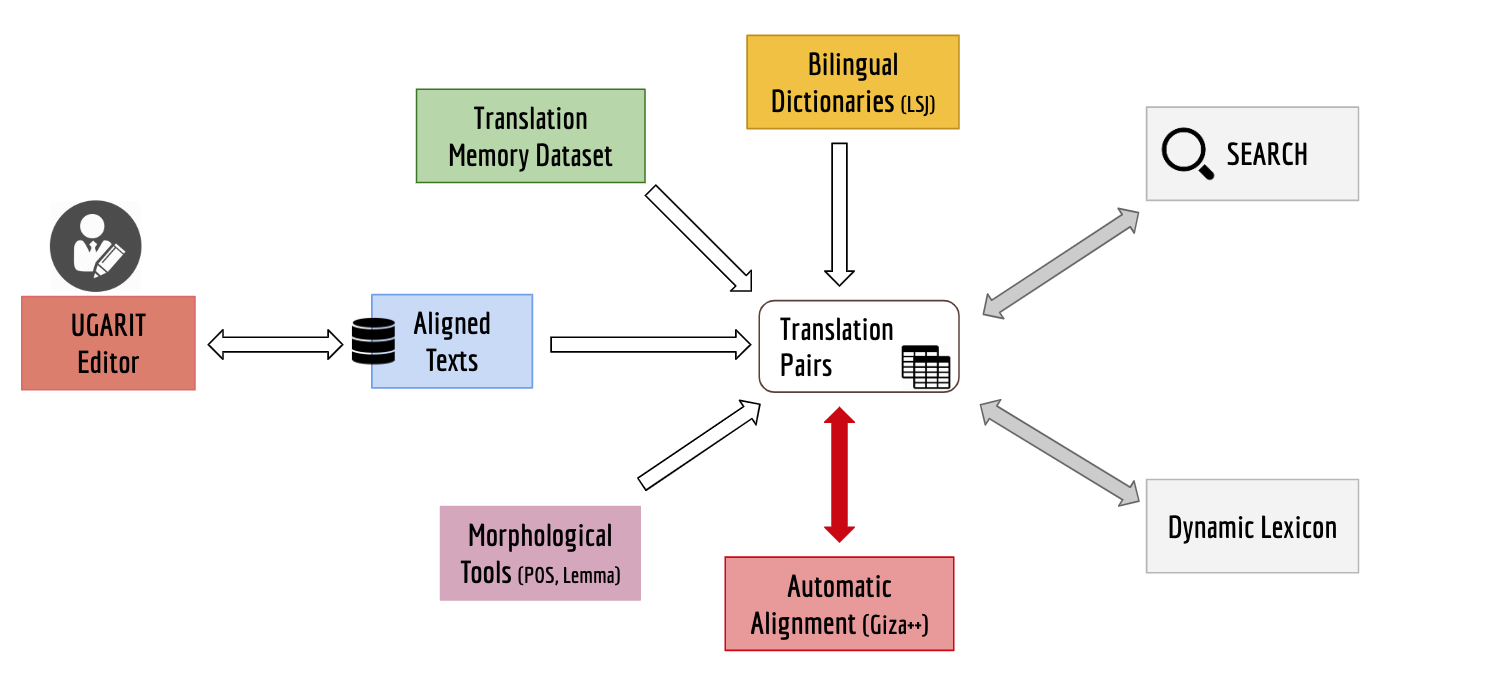

Translation pairs are stored in a local database that gathers data from the

manually aligned texts, but also from bilingual dictionaries and automatically

aligned texts with GIZA++.[5] This database would form the bulk of training data to

improve automatic translation alignment methods focusing on historical

languages.

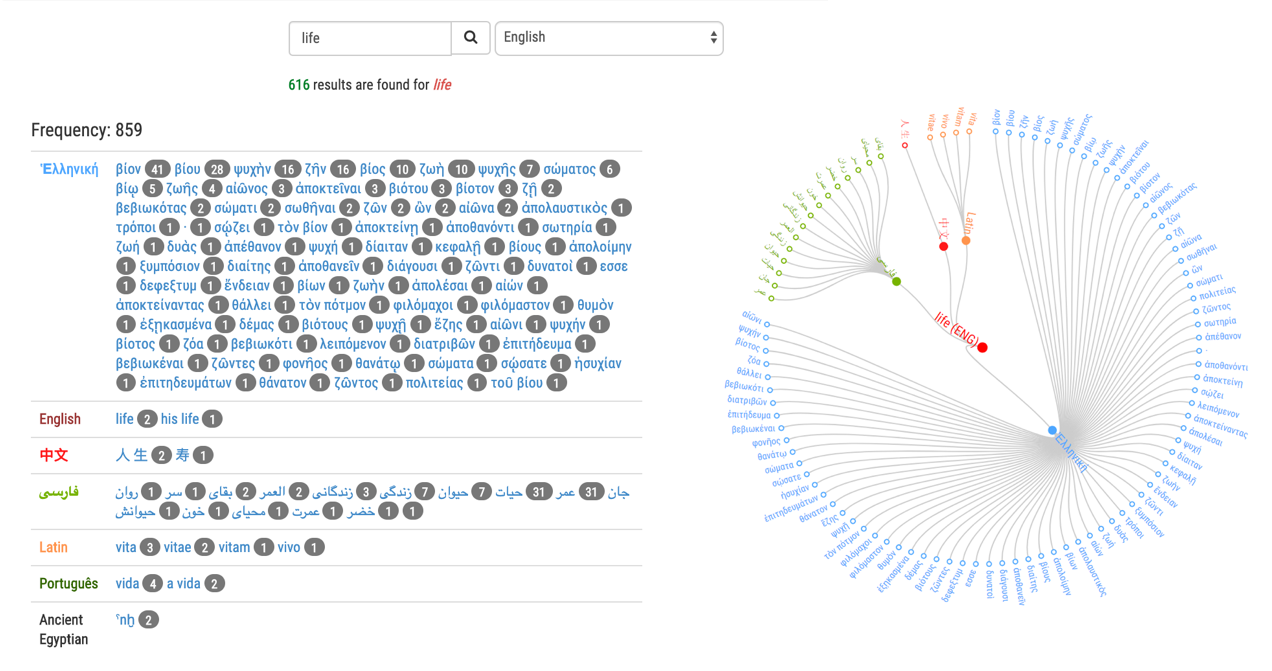

As such, the database of translation pairs serves two main functions: first, it

serves search queries to provide information on all the available translations

of a word. Therefore, if the user looks for a word (for instance, “life”)

with the search function available on the home page, the output displays all the

available aligned pairs currently hosted in Ugarit. In this way, the user can

access an extended number of translations of a word in many different

languages.

Second, Ugarit provides training data to the Dynamic Lexicon (http://dynamiclexicon.com/), which

applies the principle of triangulation to extract bilingual pairs across Ancient

Greek, Persian, and Latin, using bridge pairs in Greek/English, Persian/English,

and Latin/English: the Dynamic Lexicon fetches alignment information from all

available aligned corpora, and it uses aligned languages as pivot to fetch

translated words in other languages that may bear the same meaning [Berti and Yousef 2015]. So, each aligned pair functions as a translation

vector to access more matches in other languages that are not directly aligned.

This method is based on the assumption that two words in two given languages are

more likely to match if they are translations of the same word in a third

language [Kumar et al. 2007]. The accuracy of the triangulation can be

improved by expanding the available corpus of translation pairs, considering

available part-of-speech classification, or adding more pivot languages [Yousef 2015].

In other words, Ugarit was designed as a Citizen Science resource to collect

training datasets on historical languages from a variety of sources and

projects. One of the most important initiatives in this regard was the Hafez

Project (http://dynamiclexicon.com/hafez/; http://www.divan-hafez.com) led by

Maryam Foradi at the University of Leipzig [Foradi et al. 2017], which

tested how German and Persian speakers aligned textual portions of Hafez using

English as a bridge language. The results indicated that, provided with the

appropriate scaffolding by using English as a bridge language, users with no

knowledge of the source language could generate word alignments with the same

output accuracy generated by expert users in both languages of source and target

texts. The study showed that, while the long-term pedagogical effectiveness of

this method is comparable with learning vocabulary with flashcards, the

vocabularies learned both intentionally with flashcards and incidentally through

text alignment had a significantly better retention [Foradi 2019].

These results suggested that alignment could serve as a pedagogical tool with a

certain effect of long-term retention of vocabulary. Between 2017 and 2019, we

conducted a pilot study investigating how students of historical languages could

use translation alignment to improve their learning experience through direct

engagement with original texts. The lack of scholarship on the pedagogical

application of alignment as a tool for language learning, and the complexity

involved in the reproducibility of the experience, compel us to start with

pre-experimental observations from specific cases, where translation alignment

has been applied as a standard method during language courses. Our initial

observations provide the justification for a more experimental design.

Our Pilot Study

Ugarit was used in graduate and undergraduate semester-long Classics courses at

the Universities of Tufts and Furman, with different focuses: language (mainly

Ancient Greek and Latin) at elementary, intermediate, and upper level,

literature in translation, literature surveys, and individual research

projects.[6]

The use of translation alignment was incorporated in the teaching practice as a

structural element:

- The students made continuous use of Ugarit in class, using and creating aligned translations as a reading support.

- The task of aligning more lengthy chosen texts against one or two translations constituted the main type of assignment, in the form of individual research projects at various degrees of complexity: depending on the course and level, the students produced bilingual and trilingual alignments, whose accuracy was graded accordingly.

- The results were discussed in the form of research papers and presentations, in class and also in public venues.[7]

We observed the application of this workflow on students with very diverse

language skills, including those who mastered other modern languages, and those

whose native language was not English. We propose three cases of study:

- Students who were proficient in the source language and had complete mastery of one other language (including the native tongue).

- Students who were proficient in two different languages, and had basic knowledge of a third one.

- Students who were proficient in one or more languages, but had no prior knowledge of the source language.

Case 1: Students of the source language

Students of Case 1 were enrolled in intermediate and upper level courses in

historical languages, mainly Ancient Greek or Latin. They performed two

tasks:

- Pairwise alignment between the source text and one chosen translation in a modern language.

- Alignment of the source text against two different translations.

Example 1: Plato, Symposium 210-212. Ancient Greek-English.[8]

Graduate, native English speaker, upper level Ancient Greek. The student

created bilingual alignments of Plato’s Symposium, comparing it against the translation by Nehamas

and Woodruff (1989), in the context of a research project[9]

that integrated different levels of linguistic digital annotation, with

the goal of enabling readers with no Greek knowledge to explore the

original through the dynamic reading of the aligned parallel texts. The

student created a consistent alignment strategy that only matched words

corresponding in meaning and grammatical function (with the partial

exception of verbs for which a perfect match would not be possible, such

as subjunctives or participles with predicative use).

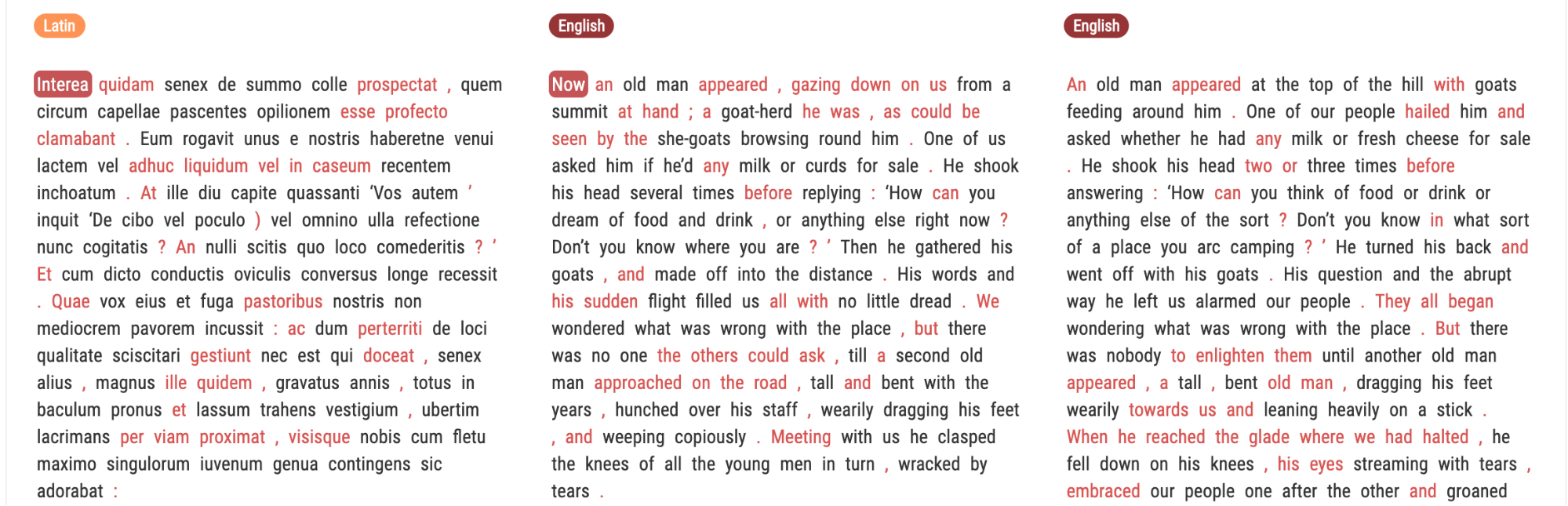

Example 2: Apuleius, Metamorphoses 8.19-22. Latin-English.[10]

Undergraduate, native English speaker, intermediate Latin. The student

performed a three-text alignment of a passage from the Metamorphoses by Apuleius, comparing the

original and two chosen English translations (A.S. Kline, 2016 and R.

Graves, 1950), to discover differences in translation strategies in a

very complex and rhetorically skilful literary work. The focus of the

observation was the semantics of different words and expressions with

potential ambiguity, but also the different ways the translators

addressed the challenges of rendering Latin syntactical structures in a

completely different linguistic system. The student then created a new

English translation, discussing where it distanced itself from the

original and which aspects were instead retained. The comparison between

two very different authorial translations proved useful to understand

different strategies of addressing relevant linguistic and semantic

problems, but also to help the student to find their own “translator’s

voice”.

Example 3: Homer, Odyssey 9.105-115. Ancient Greek-English.[11]

Undergraduate, English-Chinese speaker, upper-elementary Greek. The

student aligned the original text of Odyssey 9.105-115 against two different English

translations, in prose and poetry respectively (A.T. Murray, 1919 and S.

Lombardo, 2000). The student used the correspondences in meaning and

words across the two English renderings to individuate possible matching

words in the Greek, specifically focusing on the potentially discrepant

translation strategies between prose and verse. Overall, the prose

translation revealed a slightly better alignment rate, but typical Greek

stopwords, such as δέ or τε, were consistently not translated in

both English versions.

Case 2: Students of a third language

The typical case for trilingual alignment was a student who was proficient in

two languages, and wished to improve a third one. The student would perform

a trilingual alignment (possibly preceded by a pairwise alignment between

the two better-known languages), systematically comparing a lesser-known

language against two translations. The student would use the knowledge of

the first two languages to leverage the obstacles in understanding the third

one, by recognizing common syntactical patterns, morphologies, or

similarities in vocabulary.

Interestingly, this case was not limited to the study of historical

languages: a collateral advantage of trilingual alignment was that students

with proficiency in a historical language could use this opportunity to

focus on another language that they knew less, often a second modern

language that they were studying at the same time.

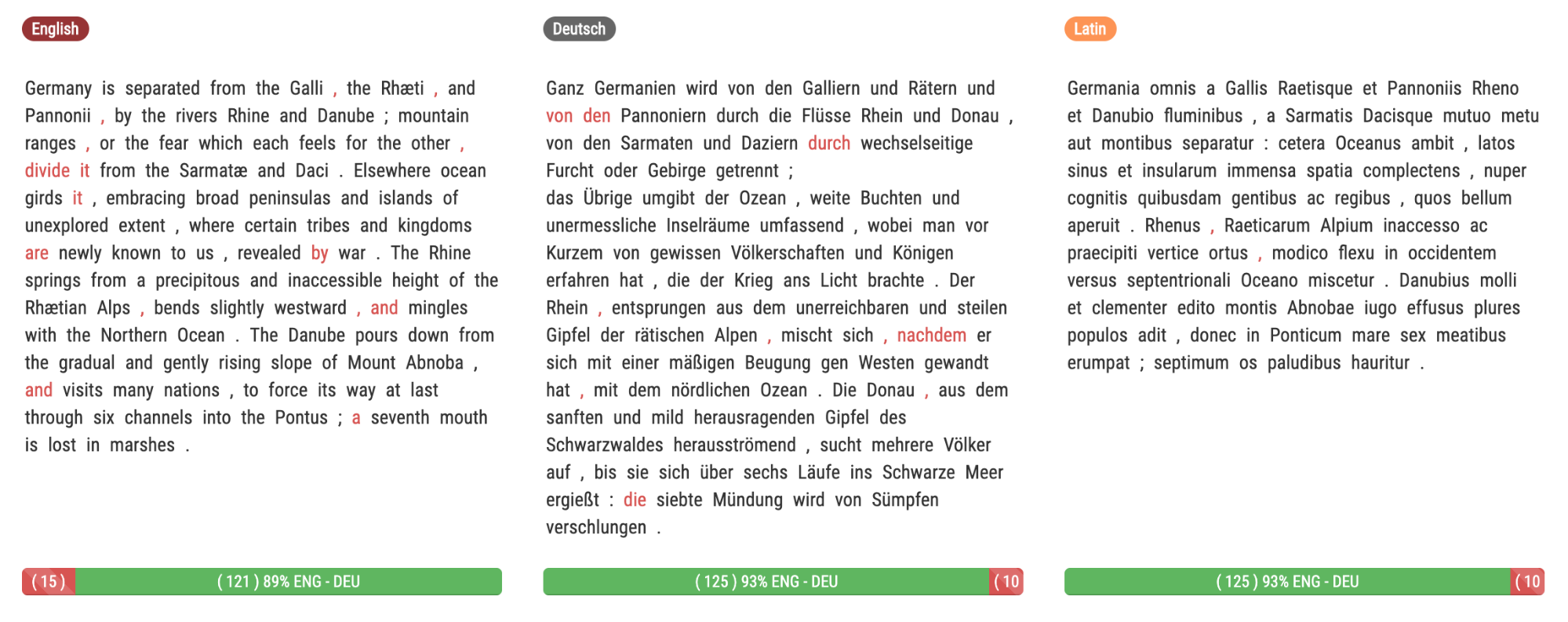

Example 1: Tacitus, Germania 1.1. English-German-Latin.[12]

Undergraduate, native English speaker, advanced Latin, basic German. The

student performed a trilingual alignment of Tacitus’ Germania, against an English and a German

translation, and used his knowledge of Latin to improve his mastery in

German. In his final report, he observed higher matching rate between

the two inflected languages than with English: rather paradoxically,

comparing German and Latin resulted easier than English and Latin. The

English translation chosen was, on the other hand, approached with some

criticism, because of its lengthy rendering of expressions that resulted

equivalent in German and Latin.

Example 2: Loqman Fables. Arabic-French-Ancient Greek.[13]

Graduate, advanced French, intermediate Ancient Greek, basic Arabic. The

student performed a trilingual alignment of the famous Loqman fables, to

pursue a research project that focused on gathering systematic evidence

of the relation between Loqman and the Aesopic corpus, which the sage is

often said to have translated [Heller and Stillmann 2012]: the student

aligned the original Arabic and the corresponding text of the fables

from the Aesopic corpus, using the French translation of Loqman as a

pivot between the two languages. The high matching rate across the three

versions, and the often verbatim correspondences between the Arabic

version and the Aesopic fables, provide the first dataset of

analytically collected evidence of the dependence between the Loqman and

the Aesopic corpus.

Example 3: Sophocles, Ajax 646-692. Ancient Greek-Chinese-English.[14]

Graduate, Chinese native speaker, English as second language,

intermediate Ancient Greek. The student performed a trilingual alignment

of Sophocles’ Ajax, aligning the Greek

text, the English translation by Sir R.C. Jebb (1896), and a Chinese

version based on the English. While the Chinese and the English

obviously displayed a higher matching rate, the student was able to use

the knowledge of both languages to individuate correspondences with the

Greek, and also to establish where there was no available match for

Greek words or concepts.

Case 3: No prior knowledge of the source language

The third case involved students, enrolled in courses on culture or

literature, who had no prior knowledge of the source language and were also

not studying it. The students were given short sections of a source text and

corresponding translations in various languages, and performed several tasks

aimed at gradually building a critical approach to the original:

- Individuate single words in the source text, such as “holy”, “honor”, or “love”, and align them with the corresponding words in a translation in a chosen language. The goal of this exercise was to develop an understanding of the depth of crucial cultural concepts, by assessing the many different ways in which the same word in the source text could be translated.

- Compare how specific expressions were rendered in two translations, and then align them against the source text.[15] The students focused on different ways of conveying morphosyntactic constructs across languages, critically approaching different translation strategies.

- Complete bilingual or trilingual alignment of a short passage, with intensive and systematic analysis of the linguistic and expressive content. The purpose of this exercise was to let students assess the linguistic differences between the languages in question, and partly to demonstrate to them that they could, in fact, approach a text in a language that they did not know at all, by means of translation alignment.

Example 1: Herodotus, Histories 1.35. Ancient Greek-English-Latin.[16]

Undergraduate, native English speaker, advanced Ancient Greek, no Latin.

The student used trilingual alignment to verify whether the knowledge of

Greek, with English as a bridge language, could serve to leverage the

unfamiliarity with a text in Latin. The passage chosen, from Herodotus’

Histories, was aligned in the original

Greek, against the English translation by A.D. Godley (1920), and the

Latin version by J. Schweighaeuser (1824). The experiment proved

successful: the student was able to recognize cognate words and match

them with the corresponding Greek, and to use the knowledge of inflected

languages to compare parts of speech between Latin and Greek (for

example, to identify the accusative fratre-m based on the similar ending with the Ionic Greek

ἀδελφεό-ν).

Example 2: Euripides, Bacchae 395-399. Ancient Greek-Chinese-English.[17]

Undergraduate, Chinese native speaker, English as second language, no

Ancient Greek. The student created a trilingual alignment of Euripides’

Bacchae, comparing the English translation by I. Johnson (http://jelks.nu/libri/classics/bacchae.html) and a revised

Chinese version based on the English (as there were no available Chinese

translations of the original Greek). As a Chinese native speaker, the

student used Chinese as a bridge to establish accurate correspondences

between the English and the Ancient Greek words that had never been seen

before. The result was an investigation into the meaning of Ancient

Greek concepts through a meaningful comparison with similar Chinese

terms, often with an emphasis on imperfect grammatical and semantic

correspondences between the Greek and its translation (such as τὸ σοφόν, “cleverness”, translated as

“being clever”).

Observations

At the end of the course all the students, no matter what level of mastery

they had of the languages, developed an acute sense of how limited their

understanding of the source text was from the translation, as much as the

critical recognition that they could convey in-depth knowledge of critical

cultural concepts expressed in the source language, by contrasting them with

their modern language translation and investigating into their various

meanings [Crane 2019]. The recognition of the limited

capabilities of translation to efficiently convey concepts in Classical

languages, while at first caused disappointment and criticism, convinced the

students of the need to look more in depth into the original language to

understand its inherent characteristics and the way it expressed ideas [Palladino 2020].

Students of the source language developed a tangible sense for the fluidity

of translation by evaluating different strategies employed by professional

scholars to approach complex phenomena; they systematically approached

complex morphosyntactic constructs and were compelled to discuss their

function and significance, while assessing the necessary imperfect character

of any translation of them. In addition, students who were experimenting

with learning a new modern language could approach unknown expressions and

vocabulary by using their skills in other languages as a bridge to convey

similar constructs.

One of the most relevant outcomes of this study was that students with no

prior knowledge of the source language could start learning it by directly

reading original literary texts. This approach could be revolutionary in the

field of slow reading and language learning, and it also promises

non-trivial consequences for passive users: readers with no knowledge of a

source language could easily use already available alignments to perform a

dynamic reading of the original aligned with its translation, gaining a

basic understanding of vocabulary and syntax in the original.

Limitations and Future Work

We hope to have shown the pedagogical potential of translation alignment.

However, we are also aware that significant implementation needs to be

pursued to improve some underdeveloped aspects and to allow a more

systematic use of a translation alignment interface in teaching

practices.

We recognize that at the moment the tool is open to every category of user,

and the aligned pairs are partly the result of unsupervised work, which may

affect the quality and consistency of the information collected in the

database. The lack of a suitable evaluation/correction workflow not only

makes the dataset not accurate enough for machine translation, but also

prevents organic teacher supervision. Therefore, the integration of a voting

system for the evaluation of the accuracy by teachers or expert users is one

of the most needed implementations. A related problem is the current

impossibility of working on collaborative projects, where multiple users can

work together on the same corpus.

Secondly, not all translation pairs are equally useful as training data. We

should expect alignment to produce conflicting, mutually exclusive, results:

after all, translation alignment is the result of interpretation, and not

all cases are easily classifiable as “right” or “wrong”. In some

cases, typically literary texts, it is extremely difficult to establish

perfect or even partial correspondences between expressions and concepts in

potentially very different languages: we have found that, in lack of

specific guidelines or gold standards for each single language pair, users

tend to create their own set of rules to keep a consistent alignment

strategy, but these rules tend to be very different according to the

particular purpose of the alignment. Therefore, we need a system to filter

translation pairs: an option would be to allow users to classify different

kinds of translation pairs, for example distinguishing categories such as

“perfect/complete” or “partial/incomplete”, and “literal”

or “free/poetical”.

Finally, we recognize that immediate access to part-of-speech tagging and

available word pairs while performing the alignment would enormously impact

on the work of non-specialized users and students, and obviously on the

improvement of analytical passive reading. This very desirable additional

feature is also included in our future implementation.

Notes

[1] In digital environments, annotation is the operation of

attaching additional information to a resource or a specific part of it: an

annotation can be unstructured, such as a comment, or structured, such as a

machine-actionable citation identifying a text [Romanello and Pasin 2013].

[2] A text and its translation or translations

placed alongside are defined as parallel texts. Large collections of

parallel texts are called parallel corpora, such as the European Parliament

Proceedings (http://www.statmt.org/europarl/) or the Bible Corpus [Christodouloupoulos and Steedman 2015]. Large research infrastructures like

CLARIN (https://www.clarin.eu/resource-families/parallel-corpora) host

big collections of parallel corpora in multiple languages as a resource for

automatic translation and linguistic research. The use of parallel corpora

in translation management systems is increasingly popular: commercial tools

like SDL Trados (https://www.sdltrados.com/), MemoQ (https://www.memoq.com/), or Across

(https://www.across.net/)

allow professional translators to manually align sentences while performing

their work, at the same time keeping consistency in the translation.

[3] For

current issues in using Glosbe for statistical machine translation, see Berti (2015).

[4] Since the short vowels in

Arabic and Persian are not written, the model used here needs to be improved

to increase the readability of the transliterated text.

[5] GIZA++ (http://statmt.org/moses/giza/GIZA++.html) is a popular program,

created as an implementation of the famous IBM models 1-5, which provides

automatic alignments of words or phrases to implement statistical machine

translation.

[6] See, for instance, Example 1 of Case

1, where alignment was part of a complete digital project.

[7] In 2018, Furman

students presented their projects at two undergraduate conferences,

at UNC Greensboro and University of South Carolina

respectively.

[15] A

strategy fully developed in Case 1,

above.

Works Cited

Babeu 2019 Babeu, A. “The

Perseus Catalog: of FRBR, Finding Aids, Linked Data, and Open Greek and

Latin.” In Berti, M., Digital Classical

Philology. Ancient Greek and Latin in the Digital Revolution. De

Gruyter, Berlin-Boston (2019): 53-72.

Berti and Yousef 2015 Berti, M. and Yousef, T.

“The Digital Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum and the

Ancient Greek-Latin Dynamic Lexicon.” In Passarotti, M., Mambrini,

F., and Sporleder, C. (eds), Proceedings of the Workshop on

Corpus-Based Research in the Humanities (CRH), 10 December 2015

Warsaw, Poland. Institute of Computer Science: Polish Academy of Sciences,

Warsaw (2015): 117-123.

Brown et al. 1990 Brown, P. F. et al. “A Statistical Approach to Machine Translation.”

Computational Linguistics 16.2 (1990):

79-85.

Christodouloupoulos and Steedman 2015 Christodouloupoulos, C. and Steedman, M. “A Massively

Parallel Corpus: the Bible in 100 Languages.”

Language Resources and Evaluation. Vol. 49.2

(2015): 375-295.

Crane 2019 Crane, G. R. “Confronting Complexity of Babel in a Global and Digital Age. How can you

work with a language that you do not know?” DH2019: Digital

Humanities Conference, University of Utrecht, July 9-12. Book of Abstracts. https://dev.clariah.nl/files/dh2019/boa/0611.html.

Dagan et al. 1999 Dagan, I. et al. “Robust Bilingual Word Alignment for Machine Aided

Translation.” In Armstrong, S. et al. (eds), Natural Language Processing Using Very Large Corpora. Springer

Netherlands, Dordrecht (1999): 209-224.

Foradi 2019 Foradi, M. “Confronting Complexity of Babel in a Global and Digital Age. What can you

produce and what can you learn when aligning a translation to a language

that you have not studied?” DH2019: Digital Humanities Conference,

University of Utrecht, July 9-12. Book of Abstracts. https://dev.clariah.nl/files/dh2019/boa/0611.html

Foradi et al. 2017 Foradi, M., Yousef, T., and

Palladino, C. “IAligner e o Editor

Ugarit Em Projetos de Ensino - Aprendizagem e Alinhamento de

Tradução.” Seminar presented at “Do Texto Clássico ao Cibertexto: 50 anos do

Curso de Grego Antigo de Araraquara.” UNESP Araraquara

and Mackenzie University São Paulo (2017).

Graça et al. 2009 Graça, J. et al. “Building a Golden Collection of Parallel Multi-Language Word

Alignment.” LREC (2008).

Heller and Stillmann 2012 Heller, B. and

Stillmann, N. A. “Luḳmān.” In Bearman, P. et al.

(eds) Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill

Online Reference Works (2012). Accessed May 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0586.

Kay and Röscheisen 1993 Kay, M. and Röscheisen, M.

“Text-translation alignment.”

Computational Linguistics 19.1 (1993):

121-142.

Kumar et al. 2007 Kumar, S., Och, F., and Macherey,

W. “Improving Word Alignment with Bridge Languages.”

In Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Empirical Methods

in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning

(EMNLP-CoNLL). Association for Computational Linguistics, Prague

(2007): 42-50.

Melamed 1998 Melamed, I.D. “Manual Annotation of Translational Equivalence: The Blinker

Project.”

IRCS Technical Reports Series (1998). https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/54.

Palladino 2020 Palladino, C. “Reading Texts in Digital Environments: Applications of

Translation Alignment for Classical Language Learning.”

Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 18.

https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/reading-texts-in-digital-environments-applications-of-translation-alignment-for-classical-language-learning/

Romanello and Pasin 2013 Romanello, M. and

Pasin, M. “Citations and Annotations in Classics: Old

Problems and New Perspectives.”

Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on

Collaborative Annotations in Shared Environment: Metadata, Vocabularies and

Techniques in the Digital Humanities, ACM, New York (2013).

Véronis 2000 Véronis, J. Parallel Text Processing: Alignment and Use of Translation Corpora.

Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht-Boston-London (2000).

Wolf 2018 Wolf, M. Reader, Come

Home. The Reading Brain in the Digital World. Harper, New York

(2018).

Yousef 2015 Yousef, T. Word

Alignment and Named-Entity Recognition Applied to Greek Text-Reuses.

Master Thesis, University of Leipzig (2015).

Yousef 2019 Yousef, T. “Ugarit: Translation Alignment Visualization.” In LEVIA’19: Leipzig Symposium on Visualization in Applications

2019. Leipzig.

Yousef and Jänicke 2020 Yousef, T., and Jänicke,

S. “A Survey of Text Alignment Visualization.”

IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer

Graphics PP (October): 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2020.3028975.