Abstract

The proliferation of tools that enable anyone to create visualizations of their

data, even with limited experience or skills, has made data visualization more

accessible than ever before. This is true in its use in both teaching and

learning, as data visualization has increasingly taken on an important

pedagogical role in the classroom and in scholarly research. However, with this

proliferation of tools there has been a concomitant awareness that visualization

needs to be employed through a critical lens that acknowledges its

constructedness as explanatory medium and as a product of situated knowledges.

Here, I describe one approach to teaching this notion of constructedness via a

framework oriented around information literacy, which encourages critical

engagement with data, the tools we use to interrogate them, and the

visualizations we design to represent them. I describe this approach through a

collection of “critical dichotomies” used to evaluate the

authority and value of visualizations, which are mapped to a subset of the core

information literacy competencies defined in the ACRL

Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education. To put these

dichotomies into practice, I further describe an interactive activity called

“Choose Your Own Adventure, with Data

Visualization,” in which participants are given paper and markers to

create booklets in the style of Choose Your Own

Adventure books and asked to consider the relationship between

active choices in the design process of a visualization and how a given

visualization is interpreted. In the process, I explore how this framework can

encourage us all, as critical practitioners of visualization, to think about the

practical relationship between data visualization and information literacy more

generally.

From situated data to constructed visualization

In “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display”

(2011), Johanna Drucker urged the adoption of new language to encourage scholars

to think about data, their visual representation, and the nature of our

interpretation of them in a discourse more inclusive of humanistic and

qualitative modes of inquiry:

capta. “

Data are

capta,”

Drucker writes, continuing that data are “taken not given, constructed as an interpretation of

the phenomenal world, not inherent in it.” Whereas

capta

are collected and parametrized in ways that depend directly upon the modes

through which we observe them – an act in which we ourselves are implicated as

collectors, reporters, and creators –

data are often conceived as

existing a priori, waiting around somewhere to be observed. Thus, whereas

data presumes observer independence and absolutism,

capta acknowledges the situatedness and observer codependence

of the interpretive act. Reinterpreted through another frame, these sentiments

are echoed by scholars such as Catherine D’Ignazio and Hill et al. who write on

feminist perspectives on data, noting that feminist frameworks about the

situatedness of knowledge can be helpful for thinking about how we engage with

data and their representations as objective representations of reality [

D’Ignazio 2015]

[

Hill et al. 2016]. Zooming out further, such interrogations of the

social and technological pedigrees of objectivity and neutrality have been

increasingly found in other disciplines as well, such as science and technology

studies [

Daston and Galison 2007], critical cartography [

Crampton and Krygier 2006], and critical race theory [

Gillborn et al. 2018], to name a few.

Examined through these lenses, it appears there is no shortage of humanistic

inquiry into the privileged authority granted to objective expressions of the

phenomenal world that are pervasive in quantitative research, reinvigorated by

the data-dense environment of the current age. Moving from data to their visual

representation, then, requires few leaps to see the consequences that a

framework oriented around situated knowledge has on how we engage with the media

we use to interpret them. To think in these terms is to conceive of data

communicated in visually or graphically motivated form – a data visualization –

as constructed space, one in which the value of a visualization is inflected by

the cultural and political forces embedded within the design choices of its

creator and the interpretive act of the user. While we may perceive

visualizations as objective, complete, and authoritative [

Kennedy et al. 2016], the reality is that they too are constructed, just

as the

capta that underlie them are themselves. And yet, the

visualization still often stands for, in one-to-one identity, that which it

actually represents, as a statement of fact. As Drucker more recently notes

(2017), we continue to prioritize approaches to visualization that assume this

one-to-one correspondence:

In a representational paradigm,

the relation between data and display is uni-directional, the data

precede the display, and the data are presumed to have some reliable

representational relation to the phenomena from which they have been

abstracted. The display functions as a surrogate for the data — which is

itself a surrogate, adequate or inadequate, for some phenomena. Simply

put, the display stands for the data, is a re-presentation of the data.

But visualizations are generally taken to be a presentation, a statement

(of fact, or argument, or process), rather than a representation

(surrogate) produced by a complex process…Instead, we should consider

that visualizations are usually representations (constructions) passing

themselves off as presentations (statements of self-evident

fact).

[Drucker 2017]

Understood in this way, objectivity in visual representation is thus

inherently compromised by the intervention of human hands; when the

visualization itself stands in as surrogate for that which is beneath it, what

results is the illusion that mediated knowledge is actually absolute if

interrogated and framed in the rightly-phrased way.

These perspectives are not particularly new, but what is momentous is their

interrogation in those domains that are grappling with the role of the

computational and quantitative in the scholarly process – including digital

humanities. Across the humanities disciplines that have integrated computational

modes of analysis, data visualization (or information visualization) is an

increasingly dominant force, and as such it carries with it the requisite

challenges that accompany any new medium or discourse of analysis employed in

humanistic scholarship and teaching. Given visual representation conceived as

constructed space, how do we validate the authority and utility of visualization

as both process and artifact of research, especially with the proliferation of

tools that make creating data visualizations easy with minimal user

intervention? From a critical theory perspective, this is an important question.

To explore this question is to formulate a more holistic understanding of

visualization and its consequences in both theory and practice, one that

accounts for not only visualization in the methodological domain but also the

social, ethical, political, and epistemological ones [

Kennedy et al. 2016]. In short, this means literacies in many forms that extend beyond the written

word – numerical, graphical/visual, information – that enable the individual to

critically engage with data, the tools that organize and engage with them, and

the visual representations we craft of them to facilitate interpretation.

Becoming critical practitioners of data and visualization in this way can happen

via many modalities and in many spaces. Perhaps surprisingly, I argue that

libraries are among those spaces that are naturally positioned to encourage this

kind of engagement, given their interest in information literacy, and libraries

can offer useful entry points for considering how such literacies around data

and visualization might be integrated into the curriculum. A clear example of

this is offered by the

ACRL Framework for Information

Literacy in Higher Education, which outlines six core frames or

competencies in information literacy around which libraries are encouraged to

provide support [

ACRL Board 2016]. These frames emphasize the

theoretical underpinnings necessary for handling information with a critical

eye, defining information literacy “as

the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of

information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued,

and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating

ethically in communities of learning.” Data, as one particular

expression of information, falls within the purview of information literacy [

Koltay 2017] – and by extension, I argue, as do those

representations based on data with which we commonly engage, including

visualization.

In the Northeastern University Library, the competencies described in the ACRL Framework have become an integral component in

how concepts and principles in information design are taught in workshops,

lectures, and consultations. Given the university’s strategic orientation

towards data- and computation-motivated modes of scholarly inquiry, exploring

what it means from the perspective of librarianship to critically engage with

data visualization in increasingly interdisciplinary spaces has been a useful

exercise for collaborations with digital humanities researchers on campus. In

this paper, I describe how these elements of the Framework manifest in my approach to teaching information literacy

through data visualization. I then describe one interactive activity I have

employed to teach these concepts that comes in the form of a Choose Your Own Adventure book, using data

visualization instead of prose as the medium of narrative. In the process, I

discuss the role that data visualization can more generally play in teaching

core competencies in information literacy.

The ACRL Framework in information visualization

Although the

ACRL Framework focuses on competencies

related to critical engagement with information sources more generally, it also

provides a useful starting point for discussions on what it means to employ such

competencies specifically in the context of data visualization. The

Framework as a whole consists of six different frames,

each of which focuses on a different facet of the information creation and

consumption process:

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation as a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship as conversation

- Searching as strategic exploration

When examined from the

capta and

visualization as

constructed space perspectives described above, two of these

prescribed frames emerge as being particularly significant. In the first of

these,

Authority is constructed and contextual, the

Framework notes that the authority of information is a

product of many intersecting influences and may be fluid depending upon the

context in which it is created and used. Accordingly, mastery of this frame

indicates an understanding of “the need to

determine the validity of the information created by different authorities

and to acknowledge biases that privilege some sources of authority over

others, especially in terms of others’ worldviews, gender, sexual

orientation, and cultural orientations.” Meanwhile, the second frame,

Information creation as a process, emphasizes the idea that the

quality, meaning, and value of information is a product of the processes of

scholarship in which it is created. “Recognizing the nature of information creation,” this frame asserts,

“experts look to the underlying processes

of creation as well as the final product to critically evaluate the

usefulness of the information.” In this way, the

Framework offers a useful backdrop against which critical thinking

about information visualization can be taught.

In the Northeastern University Library, where support services are available to

researchers in the campus community around information visualization and design,

these basic concepts are taught and discussed through “critical

dichotomies” that can help guide our thinking about specific

design choices we make in the creative process of data visualization (

Figure 1). These dichotomies are conceptualized as

modes of wayfinding for evaluating the design choices we make in the process of

creating a visualization, emphasizing the idea that design is an embodied

process, not merely an endpoint. By examining these dichotomies, I argue, we can

become better-equipped to critically dissect the meaning, value, and authority

of a particular visualization, following the guidelines of the frames described

above, given the contexts in which it is created and interpreted. These

dichotomies provide a theoretical foundation upon which practical design

considerations may be evaluated and through which a

data as capta

perspective may be discussed.

The first of these dichotomies is

proxy and artifact, which

encourages design choices that principally reflect real observed changes in data

as opposed to those that suggest the appearance of patterns that are actually

artifacts of human perception. Research in cognitive science and psychology has

shown that human visual perception is susceptible to biases that can distort

what we see. Optical illusions, for example, achieve this effect of distortion

by taking advantage of the limitations and inaccuracies of human vision to

create mismatches between what the brain believes it is seeing and what it is

actually seeing. As a result, human eyes can be tricked into seeing shapes and

colors that are not physically present by merely combining elements of geometry,

color, and space to artificially alter the perspective that the brain constructs

in the process of perception [

Meirelles 2013]. In the process of

designing a visualization, these effects can arise as well in ways we may not

notice. A good example is the use of perceptually non-uniform color palettes in

visualizations, especially with respect to the widely-used rainbow color scheme,

which can produce impressions of artificial boundaries between hues and

consequently artificial boundaries in data [

Borland 2007]. In the

language of capta, the proxy/artifact dichotomy emphasizes the constructedness

of interpreted meaning in a visualization, especially when that meaning is

facilitated by design choices that prioritize approaches to visualization that

presume a visualization stands in as declarative presentation of the data that

precede it. In this sense, this dichotomy also maps to the frame

Authority

is constructed and contextual, emphasizing the role that design can

specifically play in crafting the relative perceived authority of any given

visualization.

The second critical dichotomy is

parsimony and diminishing returns.

Modeled after Edward Tufte’s data-ink ratio concept, which argues that the

amount of ink in a visualization should change proportionately with changes in

the data that such ink represents [

Tufte 2001], this dichotomy

aims to remind us that not all design choices are made equal in their

contribution to a visualization. While the addition of data, ink, and complexity

to a visualization may be accompanied by a proportional increase in meaning,

value, and utility up to a certain point, there are additions to a design of the

type that yield no appreciable return in the efficacy of what it is trying to

communicate. Thus,

parsimony and diminishing returns encourages an

economical understanding of data visualization, arguing that good design is a

careful balance between choices that maximize the message being communicated and

the aesthetics of the medium through which that communication occurs. Such a

framing encourages a tighter hermeneutical association between data and their

visualization by minimizing the space for purely positivist and representational

channels for crafting meaning in data. This dichotomy also points attention to

the notion of information creation as process, whereby the meaning and value of

a visualization is tightly coupled to the procedure by which it is created.

This dichotomy is followed by

reductionism and holism, which

describes the wide range of scales and resolutions across which visualizations

operate in practical usage. In the language of Franco Moretti, this is also

understood as the relationship between distant and close reading of a text;

through visualization, we may switch between a close reading of a set of data

that emphasizes a high degree of detail in the data or a more distant reading

that emphasizes the bigger picture of patterns in the data [

Moretti 2013]. When we design a visualization, we must maintain

awareness of these different levels of understanding as the resolution at which

we communicate our message informs the ways in which that message may be

interpreted – put another way, the ways in which our data become crafted,

composed, and graphically motivated.

Collectively, these first three dichotomies map to the Framework frame of Information creation as a process,

highlighting the reality that the design of a visualization requires an ongoing

reassessment of objectives and assumptions in the choices we make. The final

critical dichotomy, which is authority and bias, maps primarily to

the frame of Authority is constructed and contextual. In this

dichotomy, we are reminded that there is no such thing as the singular

visualization, the best possible visual representation of a set of data.

Instead, any single visualization grabs only a differential slice of a larger

narrative, and it is incumbent upon us as practitioners of information design to

remember that for any one visual representation, there are many other

possibilities that have not been expressed. In this way, signatures of authority

and bias operate in tension with one another because a visualization is at once

a statement of information authority and the product of a design process that is

intrinsically biased by the motivations of the designer and interpreter.

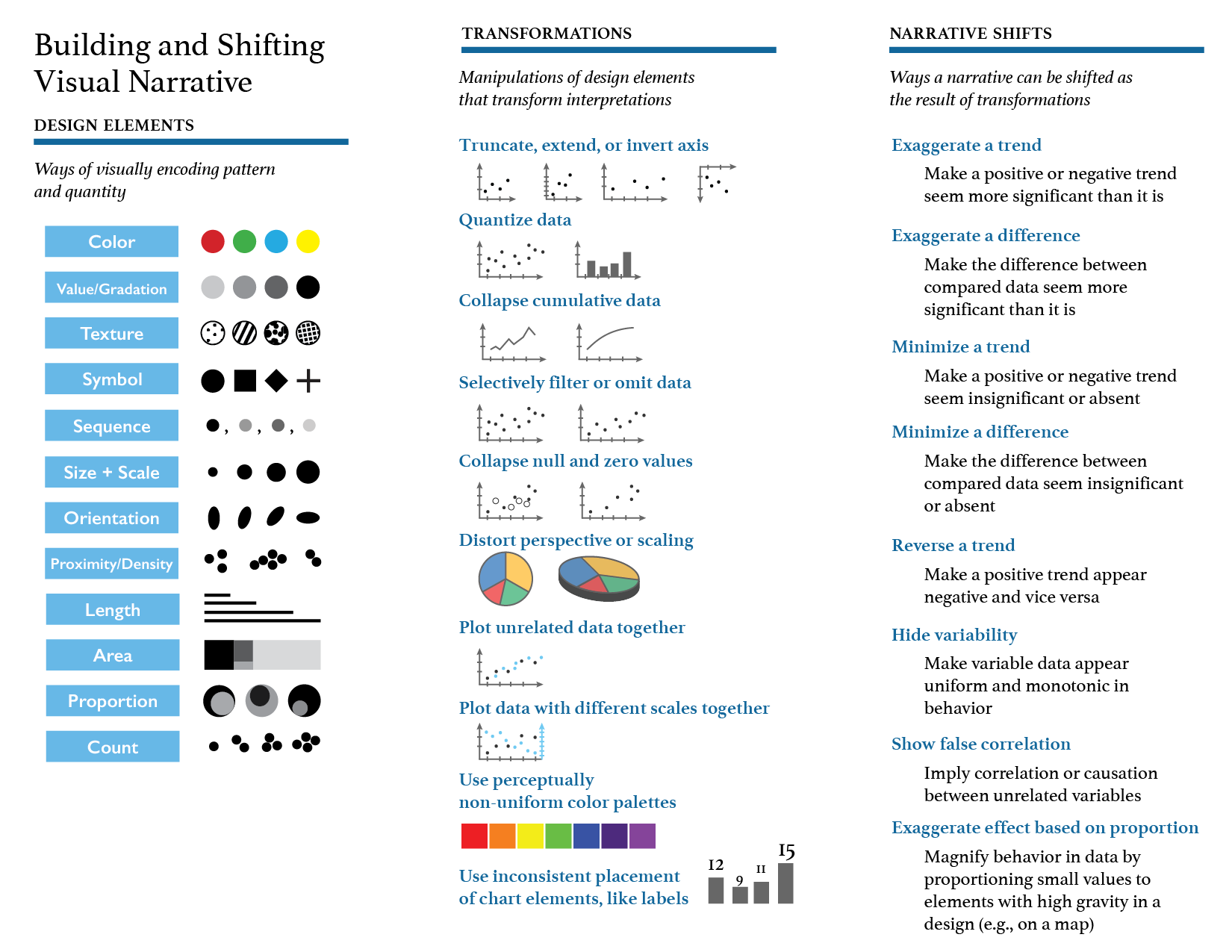

The concepts behind these dichotomies are taught in the Northeastern University

Library within a conceptual framework that discusses ways of building and

shifting visual narrative, as shown in

Figure 2.

This framework is built upon a set of design elements (i.e., preattentive

graphical elements and visual encodings used in visualization design, like

color, symbol, size, and length [

Ware 2008]) from which

transformations, or manipulations of design elements, may be used to engender

narrative shifts, or ways the meaning or interpretation of a visualization can

be shifted. These transformations and shifts include typical manipulations

commonly seen in visualizations, such as skewing or truncating axes to

exaggerate or minimize trends, as well as less noticeable manipulations, like

the use of perceptually non-uniform color palettes to exaggerate effects in data

based on proportional design area (such as when coloring geographic or cadastral

maps). By examining how these manipulations occur organically in examples of

real visualizations seen in the academic literature and popular media, students

become better-equipped to recognize manipulations in the visualizations they

produce and encounter in their daily lives.

The use of real life examples of visualizations is a good starting point to help

students understand these concepts, but I have employed other more creative

strategies for enabling students to grapple with and apply them in direct,

practical, and engaging ways. What does it mean to practically apply these

concepts in the process of visualizing data, and how do the impressions they

leave behind in the design process inform interpretation of the final

visualization created? Put another way, what does it mean to create a

visualization that is self-aware, one in which the situatedness of its data (or

capta) is faithfully communicated? In one such strategy, I devised an activity

titled “Choose Your Own Adventure, with Data

Visualization.” In this activity, participants are asked to design

their own flipbook in the style of

Choose Your Own

Adventure books

[1], which are short novels

in which the reader is invited to follow multiple different possible storylines

based on prompts that follow branching page sequences. Using this format, it

becomes possible to engage participants in discussion about how small changes in

design can result in significant changes in the meaning communicated by a

visualization, especially when framed around the critical dichotomies described

above and their correlating interpretive shifts.

Choose Your Own Adventure, with Data Visualization

In this activity, each participant is invited to create their own

Choose Your Own Adventure book using paper and

markers. The page templates, described in

Table 1,

are printed and cut out, and each participant is asked to take the required

number of pages to create their book. Markers are handed out that participants

may use for this process.

| Type |

Quantity |

| Cover page |

1 |

| Introduction: “Lo, brave traveler!” |

1 |

| Data declaration page |

1 |

| Data selection page |

1 |

| Stop page: “How will you continue?” |

As many as needed |

| Outcome page |

As many as needed |

Table 1.

Page components required for the “Choose Your Own Adventure, with Data

Visualization” activity

To begin, each participant is asked to select 2 different sets of data from a

bank of sample data provided. These data sets, examples of which are shown in

Table 2, are taken from Tyler Vigen’s website

Spurious Correlations[2], a

collection of visualizations that demonstrate humorous examples of variables

that appear to be correlated statistically but have no real-life causal

connection between them. After this, participants are asked to choose six to

eight outcomes from the narrative shift options provided, as well as two to

three different kinds of visualizations (for example, bar charts and line

charts) to use in constructing those narrative shifts. For each narrative shift

outcome, the participant draws out the different transformation step sequences

required to reach it, using the design transformation techniques presented.

Finally, once the sequential visualizations for each narrative shift outcome are

all created, the participants number the pages, fill in any page references

within the book structure, and assemble the book’s pages with a stapler.

| Year |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

| Per capita consumption of whole milk in

gallons |

|

-- |

7.7 |

7.4 |

7.3 |

7.2 |

7 |

6.6 |

6.5 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

5.7 |

| Divorce rate in Washington per 1000

people |

|

-- |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.1 |

4 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

| Per capita consumption of cheese

(pounds) |

|

-- |

29.8 |

30.1 |

30.5 |

30.6 |

31.3 |

31.7 |

32.6 |

33.1 |

32.7 |

32.8 |

| Number of people who drown by falling into a

pool |

|

109 |

102 |

102 |

98 |

85 |

95 |

96 |

98 |

123 |

94 |

102 |

| Number of films Nicolas Cage appeared in |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

| Number of people killed by venomous

spiders |

|

6 |

5 |

5 |

10 |

8 |

14 |

10 |

4 |

8 |

5 |

6 |

Table 2.

Example data sets, taking from Tyler Vigen’s Spurious Correlations

In the process of creating these books, participants are asked to think about the

design choices they commonly make when creating visualizations of their own as

well as the design elements they encounter in visualizations on a daily basis.

To guide this thinking, the following questions are asked as participants work

with their data:

- What patterns appear to be intrinsic to the sets of data being used,

and how do we validate the truthfulness of those patterns?

- What conclusions emerge organically from those patterns, and what

conclusions may be crafted?

- How do we confirm or dispute the validity of those conclusions?

- What knowledge do those conclusions impart, and how is that knowledge

motivated by the way the data are visualized?

- How can particular design choices be used to translate those patterns

into knowledge in a way that is faithful to the data themselves?

In this way, participants are encouraged to think of visualizations as

forms of dialogue rather than statements of fact – a nod to Drucker’s

characterization of the declarative nature of representational approaches to

visualization [

Drucker 2017]. When elements of design are

understood as the language and grammar used in expressing a narrative in

graphical form, it becomes easier to acknowledge the subjective nature of

visualization and representation.

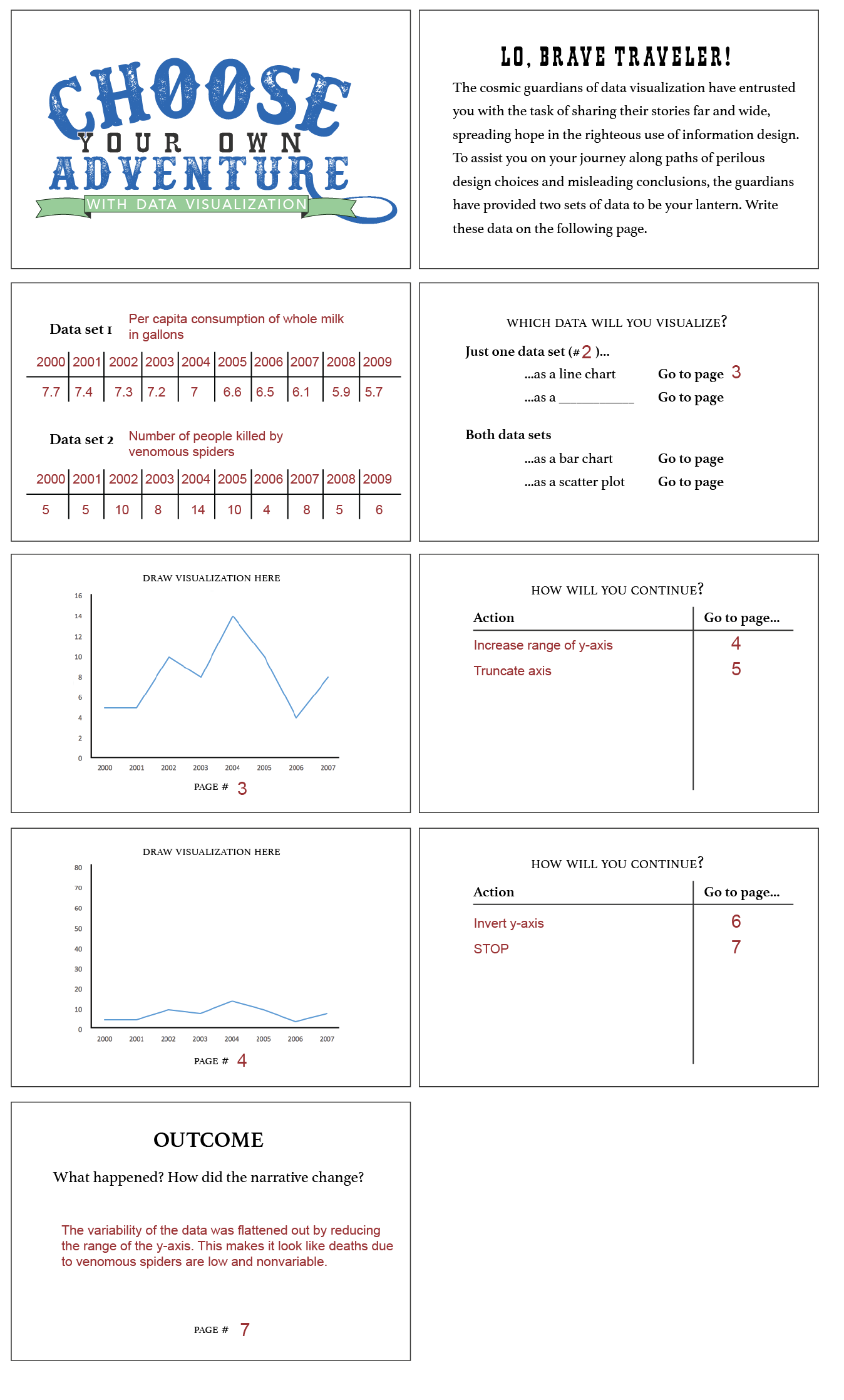

Figure 3 provides the general process for creating

a book, and

Figure 4 provides an example of a

small section from a completed book. In this example, two data sets are

selected: one about per capita consumption of whole milk in gallons from the

years 2000–2009, and another about the number of people killed by venomous

spiders over the same range of years. The book begins with an appeal to its

author:

Lo, brave traveler! The cosmic

guardians of data visualization have entrusted you with the task of sharing

their stories far and wide, spreading hope in the righteous use of

information design. To assist you on your journey along paths of perilous

design choices and misleading conclusions, the guardians have provided two

sets of data to be your lantern. Write these data on the following

page.

With this provocation, the participant is subsequently asked

to create the visualization paths for the book. In this example, the data about

venomous spider deaths is used to create a line chart. This line chart is then

manipulated by skewing the range of the y-axis, which leads to an outcome page.

Here, the outcome that results is a flattening of the variability in the data by

reducing the range of the axis, making it appear as though deaths due to

venomous spiders are low and invariable.

In this way, participants are invited to engage with the two frames from the

ACRL Framework stated above. By physically

going through the process of manipulating simple visualizations and creating

their own books, participants are invited to reflect on the idea that

information creation is indeed a process, one that is mired in a complex

intersection of influences and biases that informs how a visualization may be

interpreted. Likewise, participants also see that authority is indeed

contextual, the value and meaning of a visualization being directly dependent

upon those influences and biases. By engaging with the medium of data

visualization through the “Choose Your Own

Adventure” activity, participants are encouraged to consider what it

means to be more critical practitioners of data visualization in these frames in

their own scholarship and daily lives. And in that process, thinking about data

as capta becomes an embodied act, particularly as participants explore what it

means to parse out the design process of a visualization in a way that makes the

visualization more self-aware.

This activity has been attempted twice, and both times it was received well

overall by participants, who found it to be an exercise that was both useful and

fun for thinking about the critical choices they make when designing a

visualization. It also benefitted from the added bonus of providing participants

with something tangible to take away from the workshop, to which they could

refer in the future when designing their own visualizations. The only major

challenge to the activity is the often limited availability of time – at least

one hour is needed to provide plenty of space for creative expression and

critical assessment.

The materials for these pages are available in the Northeastern University

Library Digital Repository Service

[3]. In the future, it

may be possible to create an online interactive version of this exercise that

automates the creation of pages while enabling users to create and manipulate

their visualizations within a graphical user interface.

Conclusion

As data visualization becomes an increasingly important and common tool in

scholarship and teaching, there has been a concomitant increase in the

recognized importance of being able to engage with visualization critically.

Here, I described one approach to supporting this kind of critical engagement as

expressed through competencies in information literacy, leveraging the ACRL Framework, a collection of critical dichotomies

for evaluating visualizations, and an activity that seeks to teach these

concepts in the format of a Choose Your Own

Adventure book. Collectively, this approach emphasizes the active

role the individual plays in designing and interpreting visualizations,

encouraging students to interrogate what it means to conceptualize visualization

as a creative, constructive medium where representation is discursive rather

than absolutely defined.

Designing for data visualization in this way requires a holistic view of the

complex relationships that exist between all entities involved, including data,

representation (visualization), designer, and user. When considered as a complex

system of interactions and conversations between these entities, the design of a

visualization becomes an exercise in which we are actively engaged with the

discursive dimensions of data and information. This discursive dimension is a

reflection of Drucker’s definition of capta, which

emphasizes the ways in which we are fundamentally implicated in the construction

of data and their representation we may conventionally perceive as static,

absolute, objective, and authoritative. An understanding of these relationships

is essential for engaging holistically with visualization as a medium of

knowledge, and as a result, it is important to acknowledge the influence that

our conceptions of information, knowledge, and the relationship between them –

as evidenced by the critical dichotomies described above – impart to the design

process.

Through creative activities like the one described here, it becomes easier to

effectively teach core competencies around critical thinking in information

design, especially when framed around concepts in information literacy. As

information design is itself a creative act, pedagogical approaches that are

inherently creative and experientially oriented can play a significant role in

generating tangible, hands-on understanding of highly abstract concepts. In the

process, students can be encouraged to assess the ways in which they form

relationships between information and their representation, at the same time

tuning into the constructedness of data. By understanding visualization as a

medium for exposing these relationships, students can become better equipped to

be critical practitioners of all forms of visual representation, not only as

designers but also as consumers.