Abstract

Coptic represents the last phase of the Egyptian language and is pivotal for a

wide range of disciplines, such as linguistics, biblical studies, the history of

Christianity, Egyptology, and ancient history. It was also essential for

“cracking the code” of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Although digital

humanities has been hailed as distinctly interdisciplinary, enabling new forms

of knowledge by combining multiple forms of disciplinary investigation,

technical obtacles exist for creating a resource useful to both linguists and

historians, for example. The nature of the language (outside of the

Indo-European family) also requires its own approach. This paper will present

some of the challenges -- both digital and material -- in creating an online,

open source platform with a database and tools for digital research in Coptic.

It will also propose standards and methodologies to move forward through those

challenges. This paper should be of interest not only to scholars in Coptic but

also others working on what are traditionally considered more “marginal”

language groups in the pre-modern world, and researchers working with corpora

that have been removed from their original ancient or medieval repositories and

fragmented or dispersed.

The dry desert of Egypt has preserved for centuries the parchment and papyri that

provide us with a glimpse into the economy, literature, religion, and daily life of

ancient Egyptians. During the Roman period of Egyptian history, many texts were

written in the Coptic language. Coptic is the last phase of the ancient Egyptian

language family and is derived ultimately from the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs of

the pharaonic era.

Digital and computational methods hold promise for research in the many disciplines

that use Coptic literature as primary sources: biblical studies, church history,

Egyptology, linguistics, to name a few. Yet few digital resources exist to enable

such research. This essay outlines the challenges to developing a digital corpus of

Coptic texts for interdisciplinary research — challenges that are both material

(arising from the history and politics of the physical corpus itself) and

theoretical (arising from recent efforts to digitize the corpus). We also sketch out

some solutions and possibilities, which we are developing in our project Coptic

SCRIPTORIUM.

Digital Humanities has defined itself as a field that can enable research on a new

scale, whether distant reading of large text corpora, aggregation of large visual

media collections, or enabling discovery in future querying and algorithmic research

[

Moretti 2013]

[

Greenhalgh 2008]

[

Witmore 2012]. Critical Digital Humanities scholars remind us that

digitization initiatives sometimes replicate the Western canon rather than expand

it, and that digitization is not in and of itself a more equitable mode of

scholarship existing outside of politics [

Wernimont 2013]

[

Wilkins 2012]. Digital tools and corpora for Coptic language and

literature, we argue, can expand humanistic research not merely in terms of scale

but also scope, especially in ancient studies and literature. Large English, Greek,

and Latin corpora — as well as the tools to create, curate, and query them — have

been foundational for work in the Digital Humanities. Computational studies on the

documents from late antique Egypt can facilitate academic inquiry across traditional

disciplines as well as transform our canon of Digital Classics and Digital

Humanities scholarship.

Part I: Shenoute of Atripe and the Scriptorium of Doom

Of the several dialects of Coptic that developed in late antiquity, the Sahidic

dialect is considered the early classical dialect. Much of the surviving Coptic

literature in Sahidic comes from one important late antique repository: the

White Monastery in Egypt. One of the most important Egyptian monasteries of the

fourth through 12th centuries, it is also known as

the Monastery of Shenoute, named after the monk who was the father, or abbot, of

the community from the 380s until his death in 465. During Shenoute’s life, the

large basilica (the community’s church building) was constructed; over the

centuries it was damaged, restored, and changed, but the basic design and

construction are from Shenoute’s tenure in the fifth century.

This community is often called the White Monastery, because of the color of the

stone used to build the church. Some of the blocks used to construct the

basilica were taken from the nearby pagan temple of Repyt (Triphis). Shenoute is

the most famous and most important leader of this monastic community, propelling

it to a position as a political and cultural center in Upper Egypt.

This monastery’s scriptorium and library were arguably the most influential in

the region. Important copies of biblical books and monastic texts written or

translated into Coptic have survived [

Orlandi 2002]

[

Emmel and Römer 2008]. Shenoute received letters from the bishop of

Alexandria, which were translated into Coptic and circulated throughout the

area. Shenoute himself is our most important and probably most rhetorically

sophisticated Coptic author [

Shisha-Halevy 1986]. And he is

particularly known for his stark, prophetic rhetoric in which he condemns

sinners, heretics, and others for their failures and predicts the coming of

God’s wrath upon them [

Schroeder 2006]

[

Brakke 2007]. The White Monastery, therefore, is one of our most

important repositories of Coptic literary manuscripts, and its corpus provides

important insights into the religious history of Christian Egypt.

For linguists and Egyptologists, Coptic’s significance lies in its position as

the last phase of the Egyptian language family. Egyptian evolved over thousands

of years from the third and fourth millennia BCE through the Byzantine era,

encompassing Old and Middle Egyptian hieroglyphs of the pharaonic periods as

well as Coptic. Because of this connection to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs,

Egyptologists, including Jean-François Champollion, used their knowledge of

Coptic to translate the hieroglyphs after the discovery of the Rosetta Stone

(e.g., see [

Champollion 1824]; [

Hamilton 2006]; [

Robinson 2012]). Coptic is written primarily in the Greek

alphabet, with some modified Demotic characters. (Demotic is the Egyptian script

used increasingly during the Hellenistic period, and it preceded Coptic as a

written language in Egypt.) The language, therefore, could be loosely understood

by the non-specialist as a language of transliteration: Egyptian grammar and

vocabulary written primarily in the Greek alphabet (with some native Egyptian

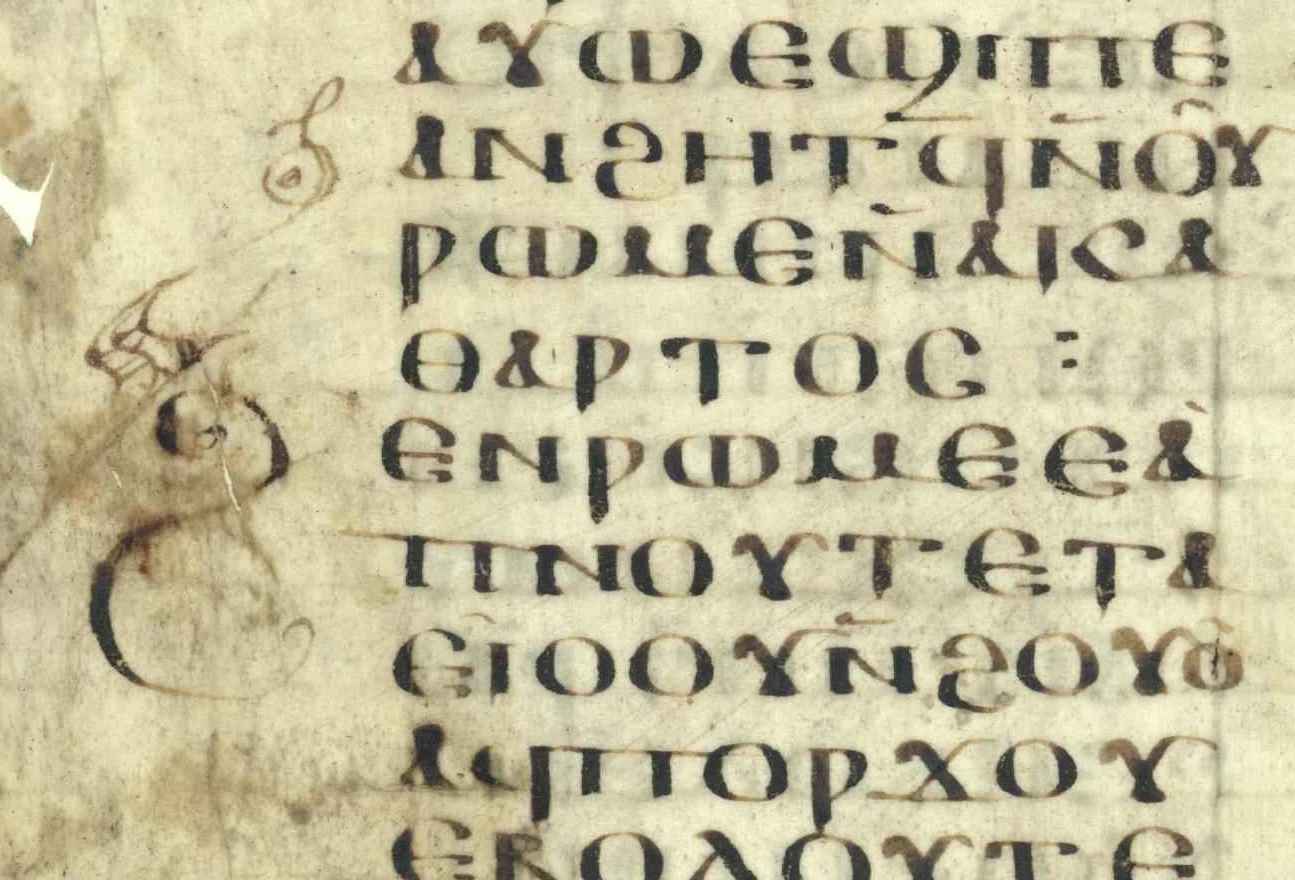

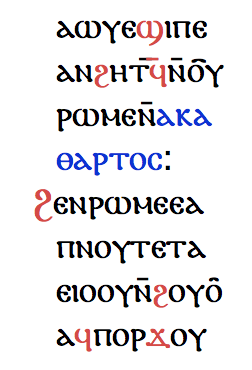

letters-Demotic-included). Figure 3 is a transcription of the detail of the

Coptic manuscript in Figure 2. The letters rendered in red in Figure 4 derive

from the Demotic (Egyptian) alphabet. Some Greek (and to a lesser extent Latin)

vocabulary words were incorporated into the language, and after the Arab

conquest, some Arabic loanwords came into the language, as well. The Greek loan

word

akathartos appears in blue in Figure 3. A

digital Coptic language corpus would be a resource for research by linguists and

Egyptologists alike.

Coptic is also important for Biblical studies, including extra-canonical texts.

Many biblical manuscripts survive in various Coptic dialects, including

important witnesses in Sahidic from the White Monastery. Shenoute of Atripe is

also one of our earliest Coptic authors to cite and quote the bible, providing

early evidence as to how the bible was used and interpreted in fourth and fifth

century Egypt. Some of our most important extra-canonical texts, including the

so-called “Gnostic” library from Nag Hammadi, survive in

Coptic. The Nag Hammadi corpus includes philosophical treatises but also a

number of extra-canonical Gospels, apocalypses, and other early Christian texts

that are fundamental to our understanding of Christian origins. The Gospel of

Thomas, shown in Figure 4, is one of the most famous of those texts.

Coptic literature documents the beginnings of the monastic movement, as well.

Egypt became one of the cradles of early Christian monasticism when in the

fourth century, men and women flocked to Egypt to become monks, and of course

Egyptian men and women themselves became monks. Perhaps the most famous of these

was Anthony the Great, who lived in a cave in the desert cliffs depicted in or

in the region of those depicted in Figure 5. Monastic settlements dotted the

Nile Valley from the fourth through eighth centuries.

Thus, Coptic literature is an important primary source for multiple academic

disciplines, and we haven't even addressed social and economic history.

Countless documentary papyri and ostraca survive, some of which are beginning to

be digitized by scholars at

http://papyri.info. Ostraca are pot sherds on which people wrote

letters, receipts, and other documents. We have thousands upon thousands of

Coptic ostraca, many of which are undocumented and unpublished, with more being

discovered all the time.

The White Monastery is arguably the most important ancient repository for Coptic

texts in the Sahidic dialect and more generally for understanding early

Christian monasticism. The community remained a literary powerhouse through at

least the twelfth century, accumulating, transcribing, and storing a wide

variety of texts. Documents from Byzantine Egypt mention people sending requests

and even visiting this monastery’s library to obtain copies of various

documents. It contains the largest, earliest collection of contemporaneous,

non-hagiographical texts documenting a coenobitic monastery. We have letters,

monastic rules, treatises and discourses from Shenoute and at least his next two

successors, comprising a corpus larger than that of any other fourth or fifth

century monastery. These documents date to a period earlier than the Benedictine

material in Italy and Europe, and they comprise a less-hagiographical (and thus

more historical) source than more well-known documents about Egypt’s

“desert fathers” and “desert mothers,”

such as saints lives about famous monks, or the

Sayings of

the Desert Fathers

[

Gregg 1980]

[

Veilleux 1980]

[

Ward 1975]

[

Wortley 2014]. When the monastery’s library was “discovered”

in modernity, its documents transformed the study of the Coptic language and

informed our understanding of the entire Egyptian language family [

Emmel and Römer 2008].

Part II: Coptic Egypt and the Last Crusade

In the 18th and 19th centuries, when Europe colonized Egypt and Africa, Europe

discovered the White Monastery library. By this time, the monastery was barely

populated, and Arabic had taken over as the popular language of Egypt. Even the

Coptic liturgies and bibles were in Arabic, not Coptic. The Coptic manuscripts,

once part of the most important library in the region, were no longer legible to

the Egyptian people, and they were dispersed to libraries, museums, and private

collections elsewhere, primarily Europe.

The actual history of the dismemberment of the library is not completely known,

but we do know that in the 18th c., pieces of this library were on the

antiquities market. Whether taken by European traders or offered up by Egyptian

Christians at the monastery, we don’t know for sure. But our first record of

White Monastery manuscripts leaving Egypt for Europe is their acquisition by the

Borgias in Italy in 1778. Most of the last of the manuscripts were found by the

French scholar Gaston Maspero in a small room, essentially discarded by people

who no longer knew Coptic, and were taken to Paris [

Orlandi 2002].

Today, the manuscripts are scattered across the globe. Only a handful remain in

Egypt. The largest collections are in Naples, Vienna, Paris, and England. The

map in Figure 6 shows only the locations of manuscripts of Shenoute’s writings.

Not where all the biblical texts are located, nor liturgical, hagiographical,

and other White Monastery texts. Including all the known White Monastery

manuscripts would add to the number of modern repositories on this map. Of

course, we do not know the number of documents (whether fragments or whole

codices) that exist in private collections.

The texts were dispersed page by page, not codex by codex. Thus, the pages of one

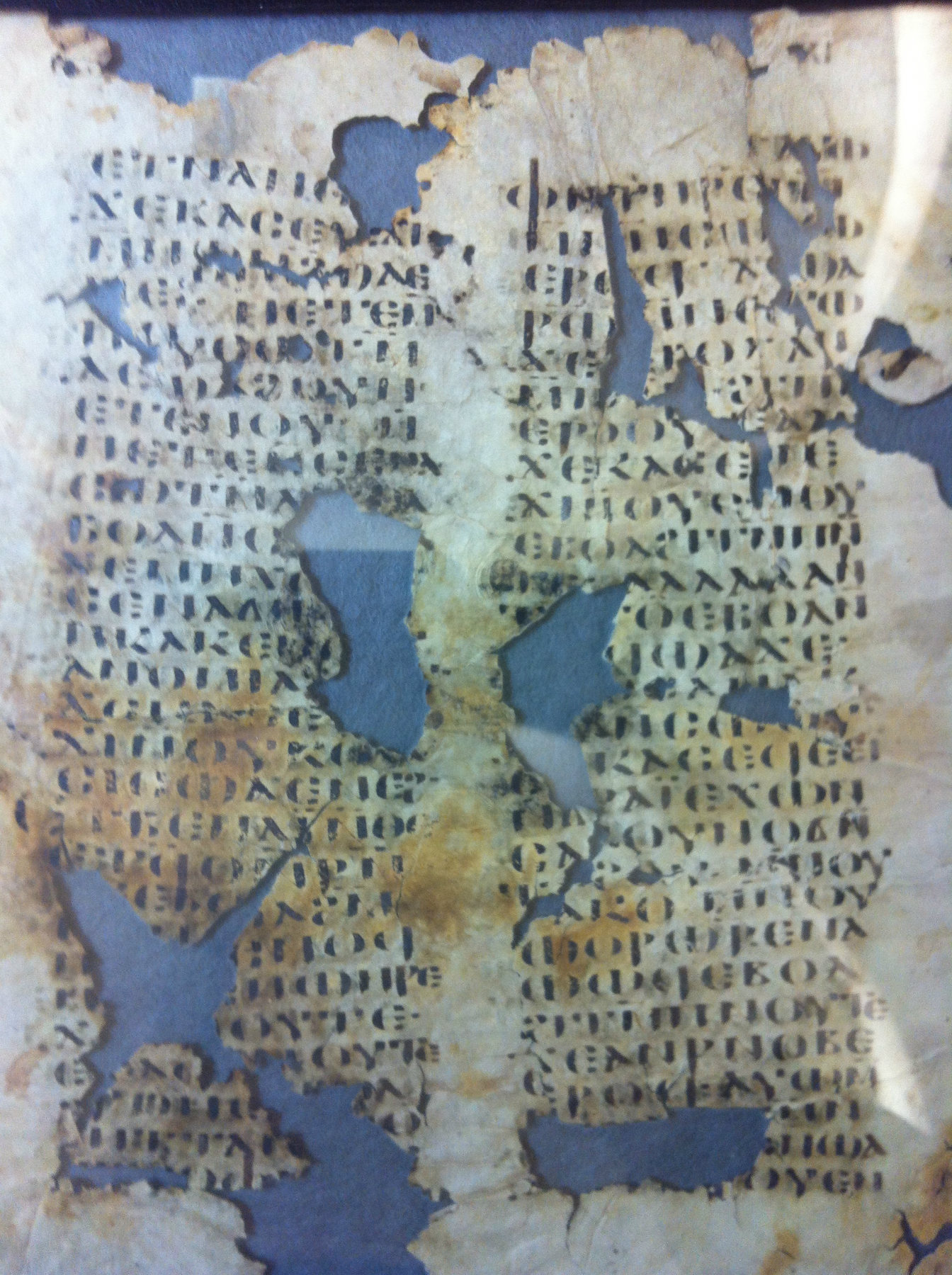

original codex might now be all over the globe. Figure 7 is a page from a copy

of Volume Three of Shenoute’s Canons for monks;

many other folios from his corpus are similarly damaged or fragmented. The chart

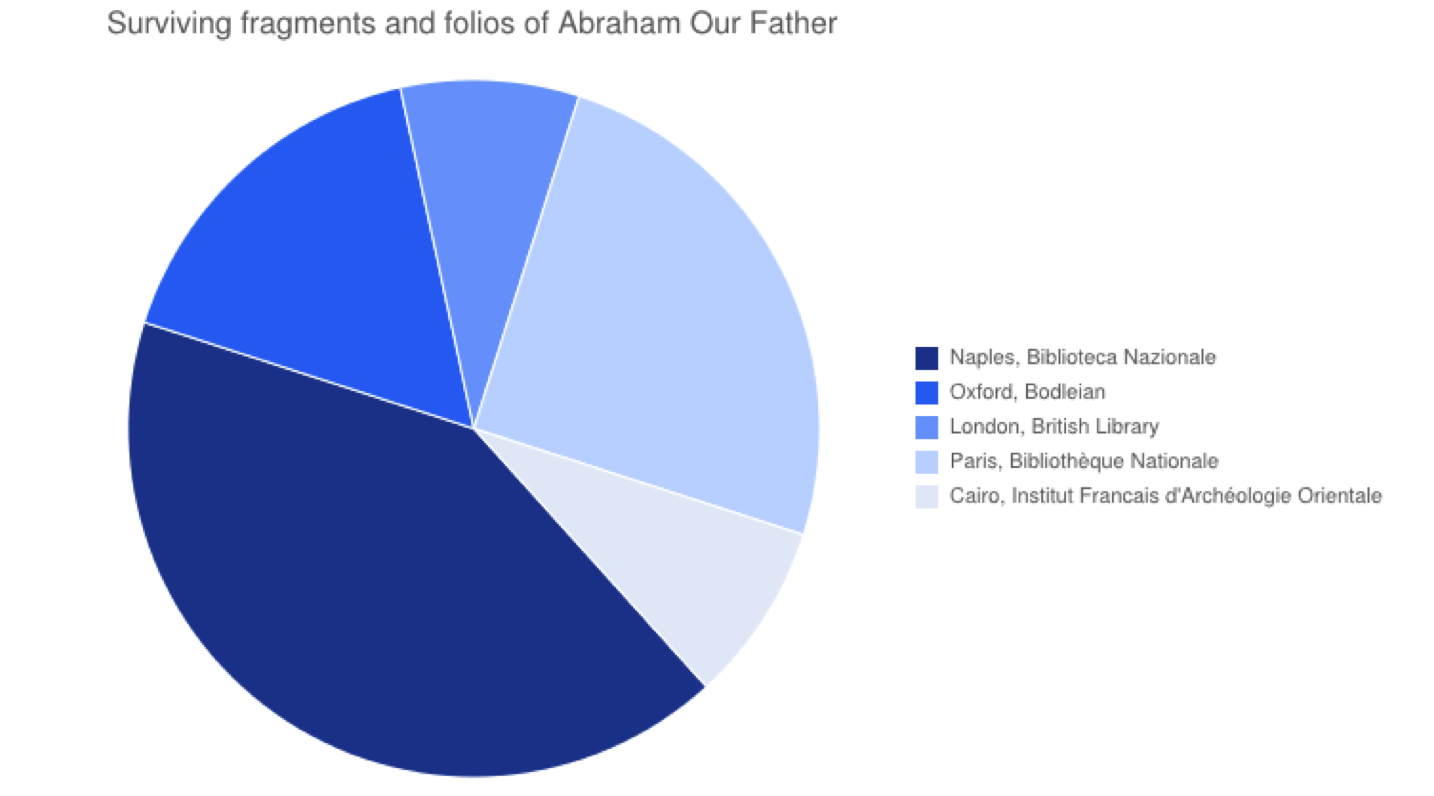

in Figure 8 illustrates the dispersal of the manuscripts of one text — not a

codex but one text — known as Abraham Our Father,

which is a letter to monks in Volume Three of Shenoute's Canons. Folios survive from a few copies of Canons vol. 3, so this pie chart represents pages from 6 separate

codices. Though six repositories are represented in the chart, each codex's

pages went to different repositories. And there are gaps; the text does not

survive in entirety even after piecing together all the surviving folios.

Less than 50% of Shenoute’s corpus survives. Of the entire library, the

percentage is probably similar, but we don’t know for sure.

Part III: The Corpus Strikes Back

One challenge with this level of corpus dismemberment is access: how can we

access these texts and understand them with both depth and breadth? What will it

require to develop and curate a Coptic corpus suitable for cross-disciplinary,

digital and computational research? Some of the challenges to developing a

cross-disciplinary digital Coptic research environment include:

- Digitization and copyright

- The patchwork nature of public domain editions

- The need for field-wide standards for stable universal references for

documents

- Integrating technologies for linguistic, historical, and codicological

research

- The need for semi-permanent archives for corpora, akin to the Perseus

Digital Library

Despite the situation of the manuscripts, the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries saw flurries in the publication of Coptic literary texts: biblical

texts, hagiography, liturgy, monastic texts, and others. Issues of access,

however, endure. Many texts remain unpublished in whole or in part, and even

more are untranslated. In the case of Shenoute’s writings, it was not even until

1993 that a scholar pieced together all the dispersed manuscripts in a

codicological reconstruction, enabling various scholars to read all the known

surviving pages of any one given text by our most important Coptic author

outside of the bible [

Emmel 2004].

Copyright and editorial issues also exist. The publication status of Coptic texts

is a patchwork, with some texts partially published and partially unpublished

due to the dispersal of their original manuscripts in multiple repositories.

Some publications are now in the public domain, while others are not. Often,

only one publication of any given manuscript exists. (And by manuscript, we

refer to the segmented pieces of codices, not entire codices.) Some older,

public domain editions are also regarded as problematic by current scholars.

Scholars working in Greek and Latin face similar obstacles in digitizing sources,

in that many desirable editions are under copyright. However, in Classics, often

there are multiple published editions of any given text, with at least one of

them being in the public domain. The Perseus Digital Library (

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu)

publishes online previous print, public domain editions. This model works for

Classical texts but is not sufficient for Coptic literature, because of the

different nature of the sources.

Additionally, since the manuscripts themselves have been dismembered, scholars

cannot rely upon a given repository and community of librarians to digitize a

vital text.

Going back to the original manuscripts for digitization is desirable for basic

reasons of scholarship and to provide a digital-native text that is not created

from published editions still under copyright. Digitizing the manuscript and

encoding all the line breaks, column breaks, page breaks, punctuation,

diacritics, and other markings enables the study of many aspects of the language

and literature. But it is also time consuming, especially when encoding texts

that have not been studied thoroughly, or perhaps have never been translated

into a modern language, or even published.

Some existing digital Coptic resources include:

A few resources are available commercially.

The field currently has no generally accepted set of data curation standards for

metadata or textual data for Coptic literature. Stable, field-recognized

identifiers and digital citation methods for Coptic literature still do not

exist. As Joel Kalvesmaki has argued, canonical referencing is complex for text

collections with such complicated histories and provenance issues [

Kalvesmaki 2014]. The Trismegistos portal provides unique

identifiers for various ancient text-bearing objects, but more work remains to

be done [

Trismegistos]. Existing publications do not even use a

common word segmentation practice for printing Coptic text. Only open,

collaborative work among various scholars and across digital Coptic projects

will ensure that each digital Coptic project does not develop its own unique

protocols and datasets that are not applicable for multiple research questions,

or that are not readable or transferrable across projects.

Martin Mueller’s keynote lecture at the 2012 Chicago Colloquium on Digital

Humanities and Computer Science noted philology’s tendency toward perfectionism

[

Mueller 2012]. Philologists' resistance to releasing editions

“too soon” bumps up against the digital scholarly world’s impulses to

release data openly and swiftly, in order to increase access to texts. The

ability to edit and annotate a digital corpus resolves some of these anxieties,

provided that the technology of the environment for the corpus enables

revisions. An example of such a corpus is the Papyri.info site, where the

Papyrological Editor enables further edits and refinements.

The recent controversy over the so-called

Gospel of Jesus’s

Wife Fragment demonstrates the necessity for an open, well-curated,

and annotated digital Coptic corpus. Harvard University announced the discovery

of a papyrus fragment containing a small portion of a Coptic literary text

containing the terms “Mary,”

“Jesus,” and “my wife” in September 2012, and a slew of media fanfare

followed, including a front-page story in the

New York

Times

[

Goodstein 2012]. The primary questions were: is this document an

authentic ancient text and does it provide evidence that Jesus was married —

possibly to Mary Magdalene? — or at least that a particular early Christian

group wrote about Jesus marrying Mary Magdalene [

Le Donne 2013]?

For two years, scholars debated the authenticity of the fragment, examining the

vocabulary, syntax, and handwriting. Similarities to vocabulary in the Nag

Hammadi Library were noted, although the grammar of the Coptic in the fragment

struck some scholars as inauthentic very early in controversy [

Robinson and Halton 2012]

[

Čéplö 2012]. And since the fragment appeared on a small piece of

papyrus, it seemed possible the text could be an amulet, spell, or prayer

fragment.

Immediately, the potential for analyzing the document against digital corpora

curated for Coptic’s particular language structure and annotated linguistically

became apparent. The lack of such corpora meant that only one scholar made such

an attempt, using a widely circulating digital version of the Sahidic New

Testament gospels and the Nag Hammadi Library’s Gospel of Thomas [

Čéplö 2012]. These digitized texts, however, however, contain many

irregularities in spelling and word segmentation, and are not annotated. While

helpful, they could not be called well-curated nor comprehensive. Scholarly

debate over the authenticity of the fragment continued, focusing on traditional

methodologies of studying ink, papyrus, handwriting, and grammar, in blogs,

social media, and traditional scholarly outlets [

Goodacre 2014b]

[

Goodacre 2014a]

[

King 2014a]

[

Choat 2014]

[

Yardley and Hagadorn 2014]

[

Azzarelli, Goods, and Swagger 2014]

[

Hodgins 2014]

[

Tuross 2014]

[

Depuydt 2014]

[

King 2014b]. Finally Coptic scholar Christian Askeland determined

the text was indeed a modern forgery, since another document using the same ink

and written in the same hand was also forged. He published his results in a blog

post and later a traditional article [

Askeland 2015]. Traditional

scholarly methodologies informed this debate, but open access corpora and images

would have accelerated the findings and would have allowed for testing of

hypotheses speculated between 2012 and 2014.

Part IV: A New Hope

A richly annotated corpus of digital Coptic literary texts in an open-access

environment, with well curated metadata, and which adheres to existing digital

and traditional field-based standards, enables the exploration of the

multidisciplinary research areas we have described. Such work requires tools to

process and annotate Coptic text, a search and visualization infrastructure, and

community-based standards. Coptic SCRIPTORIUM is developing such tools and

technologies, plus a digitized corpus created with these tools.

To create a digital corpus of Coptic texts suitable to automated search and other

digital and computational methods, new technologies must be developed

specifically for processing the Coptic language, and existing technologies must

be adapted. Such technologies include:

- Character converters to convert text visualized as

Coptic characters using legacy fonts into the Unicode Coptic character set.

Many scholars have existing digitized Coptic text on their computers, which

could contribute to a large collaborative corpus. But the transcriptions are

in legacy fonts, which need to be converted into Unicode (UTF-8)

characters.

- A tokenizer to break up Coptic word groups into their

constituent, grammatical parts. The Coptic language is agglutinative. Words

are in fact bound groups of morphemes, each with its own grammatical

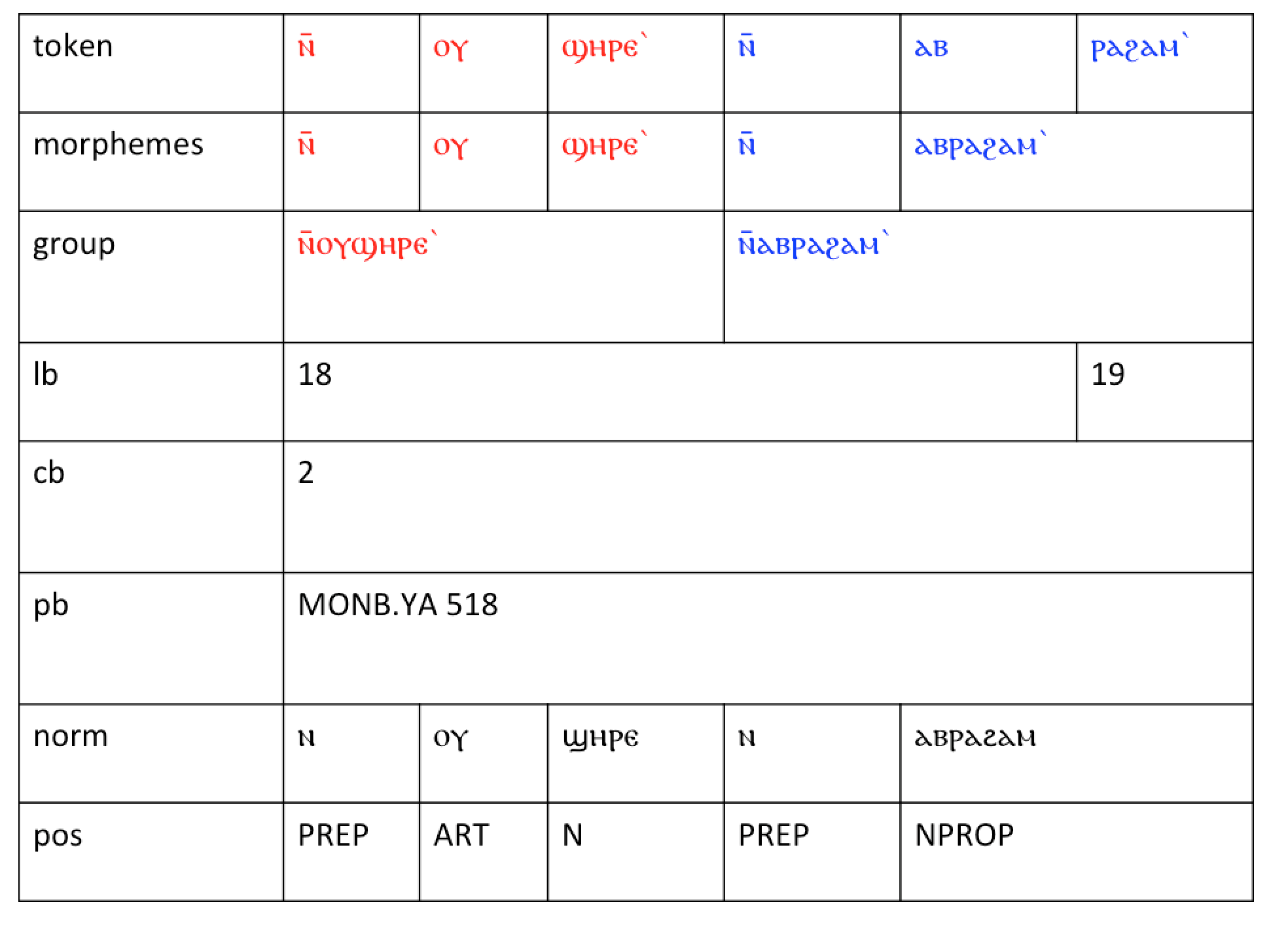

purpose. Figure 9 gives one example from the text, Abraham

Our Father, by Shenoute:

There is no universal, uniform method of word segmentation in Coptic; different

scholars have followed different guidelines. The emerging standard in the United

States is currently that of Bentley Layton, in his Coptic Grammar [

Layton 2011]. In Germany, however, some scholars follow the

paradigm established by Walter Till [

Till 1960]. Tokenizing Coptic

is essential for linguistic study, since each morpheme needs its own

part-of-speech annotation. Historical research using basic vocabulary searches

also requires tokenization. Finally, more complex research into style and

rhetoric, authorship attribution of unidentified texts, and searching for text

reuse and quotation (especially using algorithms to search for biblical

citations) demand a tokenized text

- A normalizer to standardize spelling of Coptic words

and remove or standardize diacritics and punctuation. Normalization of

spelling is essential for search, and often for further machine-enabled

annotation. Some tools to annotate the text automatically or

semi-automatically rely on consistent spelling of terms. Issues include

spelling variants due to geographical practices, scribal inconsistencies or

idiosyncrasies; expansion of scribal abbreviations for nomina sacra;

differing practices across manuscripts for diacritical marks such as

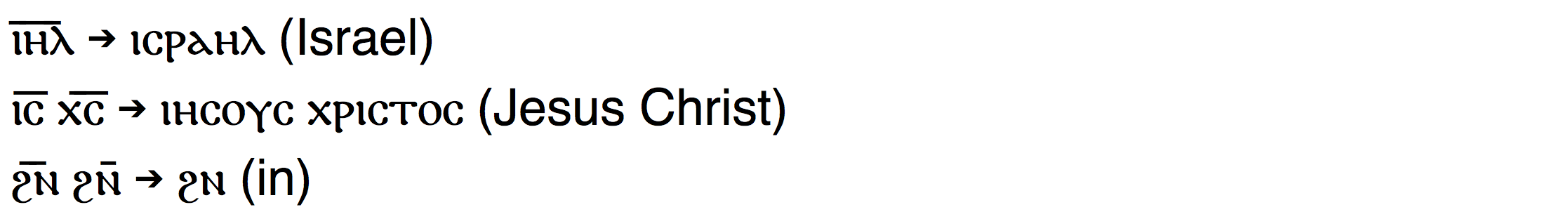

supralinear strokes or circumflexes. Figure 10 provides examples of

abbreviations to be expanded and diacritics removed:

- TEI XML [TEI]

annotation standards, specifically the EpiDoc subset,

to markup the diplomatic transcription of texts and their metadata. Encoding

standards developed by the Text Encoding Initiative [TEI] and

especially the EpiDoc subset used by epigraphers and papyrologists [Elliott et al. 2006] can be adapted for Coptic literary manuscripts.

Metadata and paleographical information can be encoded.

Other existing, community standards used in both digital and print scholarship

can be adapted, as well. Trismegistos numbers from the Trismegistos database of

ancient texts and texts-bearing objects should be included in metadata to enable

linked data across digital projects [

Trismegistos]. For works

specifically in Coptic, the CMCL abbreviations for manuscript codices (e.g.,

MONB.YA = White Monastery manuscript YA) and Clavis Coptica for authors and

texts are existing standards [

Clavis Patrum Copticorum]

[

Suciu 2012]. For texts by Shenoute, the incipits and

abbreviations for texts developed by Stephen Emmel in

Shenoute's Literary Corpus should be used for metadata [

Emmel 2004]. The field still needs a system for Uniform Resource

Names (URNs) and other more refined citation methods for curating digital data

and documents — especially given the dismembered nature of the corpus, and that

some pieces of the corpus may be published in born-digital formats while others

may be adapted from previously published editions.

Tools to annotate or mark up the digitized, curated text enable search and

computational research methods for work in a variety of disciplines need to be

developed. We know of no other open source tools to annotate digital texts in

the Egyptian language family. SCRIPTORIUM is working on the following

technologies

- A Part-of-Speech tagger automatically annotates

Coptic morphemes according to the linguistic conventions established in

Layton's Coptic Grammar (the field standard),

enabling research into linguistics and style. It uses the trainable

TreeTagger natural language processing tool [Schmid 1994].

- A lemmatizer can automatically annotate various forms

of a word to the standard, dictionary headword. The lemmatizer will enable

linking data to online lexica either at SCRIPTORIUM or elsewhere on the

web.

- A language-of-origin tagger automatically annotates

words of Greek, Hebrew, Latin, or other non-Egyptian language origin,

enabling research into loan words, language contact, and bilingualism.

- Entity taggers to annotate digital corpora for people and places to

connect literary data with linked open data initiatives such as PELAGIOS for

geographic locations in the ancient world and SNAP on ancient prosopography

are also desirable [Anon 2014]

[SNAP:DRGN]

At Coptic SCRIPTORIUM textual annotations are made using multi-layer and standoff

markup [

Carletta, Evert, Heid, Kilgour, Robertson, and Voorman 2003]

[

Dipper 2005], which can capture the variety of annotations:

linguistic, paleographic, philological, etc. The token layer is the base layer

of data, the smallest unit of data annotated, as seen in Figure 11, which shows

the annotation of two bound groups (one in red, one in blue), which translate

into “of a son of Abraham”:

The layers provide data for the morphemes, the bound group, the line number in

which the text appears in the original manuscript (lb, following the TEI/EpiDoc

standard), the column in which the text appears in the original manuscript (cb),

the page on which the text appears in the original manuscript (pb, in which

MONB.YA is the siglum for White Monastery codex YA as designated by the CMCL

standards), the normalized morphemes, and the part of speech tags for the

normalized morphemes (PREP=preposition, ART=article, N=noun, NPROP=proper

noun).

SCRIPTORIUM provides the means to search the multiple layers of data in various

combinations, including in conjunction with metadata. We use the open-source

search and visualization tool ANNIS [

Zeldes, Ritz, Lüdeling, and Chiarcos 2009]. ANNIS contains

built-in visualization capabilities and can be customized for each corpus.

Coptic SCRIPTORIUM has embedded a Coptic keyboard, a web font for Coptic Unicode

characters, and various visualizations of the data. All the tools and corpora

discussed in this essay are available at

http://www.copticscriptorium.org.

The multilayer architecture allows for multidisciplinary research [

Krause and Zeldes 2014]. Historians may be interested in vocabulary searches

on the normalized words. Linguists may query the parts of speech for

computational morphological and syntactic research. Scholars working on ancient

prosopography or network analysis may search for named entities. Additional

layers may be added if other researchers wish to annotate the corpora for other

research questions. Since all data documents are licensed with Creative Commons

Attribution licenses, philologists and paleographers who wish to publish their

own digital editions of manuscripts may download, modify, and annotate or

re-annotate our XML documents for their own work as long as they provide

attribution to the source.

The community of Coptic scholars is small, but the impact of our work ripples out

into many fields. The true hope for digital scholarship in the Coptic language

and literature lies beyond our individual efforts and in the community of Coptic

scholars within and outside the academy: scholars who digitize texts, write

annotations, inspire and develop new technologies, conduct research using the

platform, and contribute to the evolving standards.

Works Cited

Askeland 2015 Askeland, C., 2015. “A Lycopolitan Forgery of John’s Gospel”. New Testament Studies, 61(03), pp.314–334.

Azzarelli, Goods, and Swagger 2014 Azzarelli,

J.M., Goods, J.B. & Swager, T.M., 2014. “Study of Two

Papyrus Fragments with Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy”.

Harvard Theological Review, 107(02),

pp.165–165.

Brakke 2007 Brakke, D., 2007. “Shenoute, Weber, and the Monastic Prophet: Ancient and Modern Articulations

of Ascetic Authority”. In Foundations of Power

and Conflicts of Authority in Late-Antique Monasticism: Proceedings of the

International Seminar in Turin, December 2-4, 2004. Orientalia

Lovaniensia Analecta. Leuven: Peeters.

CMCL CMCL, Corpus dei Manoscritti Copti Letterari.

CMCL - Studies in Coptic Civilization.

Available at:

http://cmcl.aai.uni-hamburg.de/ [Accessed September 11, 2012].

Carletta, Evert, Heid, Kilgour, Robertson, and Voorman 2003 Carletta, J., Evert, S., Heid, U., Kilgour, J., Robertson,

J. & Voormann, H. 2003. “The NITE XML toolkit: Flexible

annotation for multi-modal language data”. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 35(3),

353–363.

Champollion 1824 Champollion, Jean-François.

Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens

Égyptiens. Paris: Treuttel et Würtz, 1824.

Choat 2014 Choat, M., 2014. “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife: A Preliminary Paleographical

Assessment”. Harvard Theological Review,

107(02), pp.160–162.

Depuydt 2014 Depuydt, L., 2014. “The Alleged Gospel of Jesus’s Wife: Assessment and Evaluation

of Authenticity”. Harvard Theological

Review, 107(02), pp.172–189.

Dipper 2005 Dipper, S. 2005. “XML-based stand-off representation and exploitation of multi-level

linguistic annotation”. In Proceedings of

Berliner XML Tage 2005 (BXML 2005). Berlin, Germany, pp.

39–50.

Elliott et al. 2006 Elliott, T. et al., 2006.

“EpiDoc: Epigraphic Documents in TEI XML”.

Available at:

http://epidoc.sf.net/

[Accessed September 11, 2012].

Emmel 2004 Emmel, S., 2004. Shenoute’s Literary Corpus, Louvain: Peeters.

Emmel and Römer 2008 Emmel, S. & Römer, C.E.,

2008. “The Library of the White Monastery in Upper Egypt/Die

Bibliothek des Weißen Klosers in Oberägypten”. In Spätantike Bibliotheken: Leben und Lesen in den frühen

Klöstern Ägyptens. Nilus: Studien zur Kultur Ägyptens und des

Vorderen Orients. Vienna: Phoibos Verlag, pp. 5–25.

Greenhalgh 2008 Greenhalgh, M., 2008. “Art History”. In S. Schreibman, R. Siemens, & J.

Unsworth, eds. A Companion to Digital Humanities.

Malden, Mass.: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 31–45.

Gregg 1980 Gregg, R.C. ed., 1980. Athanasius : The Life of Antony and the Letter To

Marcellinus, Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press.

Hamilton 2006 Hamilton, Alastair. The Copts and the West, 1439-1822 the European Discovery of

the Egyptian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Chapter

12.

Hodgins 2014 Hodgins, G., 2014. “Accelerated Mass Spectrometry Radiocarbon Determination of

Papyrus Samples”. Harvard Theological

Review, 107(02), pp.166–169.

King 2014a King, K.L., 2014a. “‘Jesus said to them, ‘My wife . . .’’: A New Coptic Papyrus

Fragment”. Harvard Theological Review,

107(02), pp.131–159.

King 2014b King, K.L., 2014b. “Response to Leo Depuydt, ‘The Alleged Gospel of Jesus’s Wife: Assessment

and Evaluation of Authenticity’”. Harvard

Theological Review, 107(02), pp.190–193.

Krause and Zeldes 2014 Krause, Thomas &

Zeldes, Amir,“ANNIS3: A New Architecture for Generic Corpus

Query and Visualization”. Digital Scholarship in

the Humanities 31(1), 118-139.

Layton 2011 Layton, B., 2011. A Coptic Grammar 3rd Edition, Rev., Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Le Donne 2013 Le Donne, A., 2013. The Wife of Jesus: Ancient Texts and Modern Scandals,

Oneworld Publications.

Moretti 2013 Moretti, F., 2013. Distant Reading 1 edition., London; New York:

Verso.

Mueller 2012 Mueller, M., 2012. “Big Data in the Humanities: Curation, Exploration,

Collaboration. In Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities & Computer

Science 2012”. University of Chicago. Available at:

http://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/dhcs/dhcs-2012-program/ [Accessed

May 19, 2014].

Orlandi 2002 Orlandi, T., 2002. “The Library of the Monastery of Saint Shenute at

Atripe”. In Perspectives on Panopolis: an

Egyptian Town from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Leiden:

Brill, pp. 211–231.

Robinson 2012 Robinson, A., 2012. Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of

Jean-Francois Champollion, Oxford University Press.

Robinson and Halton 2012 Robinson, G.

& Halton, C., 2012. “Gesine Robinson on the ‘Jesus

Wife’ Fragment”.

Charles Halton.

Available at:

http://awilum.com/?p=2216 [Accessed July 22, 2015].

SNAP:DRGN SNAP:DRGN, Standards for Networking

Ancient Prosopographies | Data and Relations in Greco-roman Names.

Standards for Networking Ancient Prosopographies.

Available at:

http://snapdrgn.net/

[Accessed October 21, 2014].

Schmid 1994 Schmid, H., 1994. “Probabilistic Part-of-Speech Tagging Using Decision Trees”. In

Proceedings of International Conference on New Methods

in Language Processing, Manchester, UK. International Conference on

New Methods in Language Processing. Manchester.

Schroeder 2006 Schroeder, C.T., 2006. “Prophecy and Porneia in Shenoute’s Letters: The Rhetoric of

Sexuality in a Late Antique Egyptian Monastery”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 65/2, pp.81–97.

Shisha-Halevy 1986 Shisha-Halevy, A. 1986.

Coptic Grammatical Categories. Structural Studies in

the Syntax of Shenoutean Sahidic. Rome: Pontificum Institutum

Biblicum.

TEI “TEI, TEI: Text Encoding

Initiative”. Available at:

http://www.tei-c.org [Accessed May 19, 2014].

Till 1960 Till, W.C., 1960. “La

séparation des mots en copte”. Bulletin de

l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 60, pp.151–70.

Tuross 2014 Tuross, N., 2014. “Accelerated Mass Spectrometry Radiocarbon Determination of Papyrus

Samples”. Harvard Theological Review,

107(02), pp.170–171.

Veilleux 1980 Veilleux, A., 1980. Pachomian Koinonia, Volume One: The Life of Saint Pachomius

and His Disciples, Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications.

Ward 1975 Ward, B. ed., 1975. The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection,

Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications.

Wernimont 2013 Wernimont, J., 2013. “Whence Feminism? Assessing Feminist Interventions in Digital

Literary Archives”. Digital Humanities

Quarterly, 7(1).

Wilkins 2012 Wilkins, M., 2012. “Canons, Close Reading, and the Evolution of Method”. In

M. K. Gold, ed. Debates in the Digital Humanities.

Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, pp. 249–258.

Witmore 2012 Witmore, M., 2012. “Text: A Massively Addressable Object”. In M. K. Gold,

ed. Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis:

Univ Of Minnesota Press.

Wortley 2014 Wortley, J. ed., 2014. The Anonymous Sayings of the Desert Fathers,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yardley and Hagadorn 2014 Yardley, J.T. &

Hagadorn, A., 2014. “Characterization of the Chemical Nature

of the Black Ink in the Manuscript of The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife through

Micro-Raman Spectroscopy”. Harvard Theological

Review, 107(02), pp.162–164.

Zeldes, Ritz, Lüdeling, and Chiarcos 2009 Zeldes, Amir, Ritz, Julia, Lüdeling, Anke and Chiarcos, Christian (2009). “ANNIS: A Search Tool for Multi-Layer Annotated Corpora”. In:

Proceedings of Corpus

Linguistics 2009. Liverpool, UK. Available at:

http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/publications/cl2009/ [Accessed September 10,

2012].