Abstract

The Almanac Archive, a project in its early stages

of development, seeks to create a corpus of annotated British almanacs from

1750-1850. Cheap and useful, the almanac was one of the most commonly purchased

and frequently read print genres during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

By focusing on readers’ annotations in almanacs about everything from social

engagements and weather to historical events and the breeding of livestock,

The Almanac Archive offers insights into

everyday life and ideologies of time. Creating a searchable, digital corpus of

high-resolution images from annotated almanacs will encourage new research

questions about the relationship between historical events, individuals’

everyday lives, and the materiality of Romantic-era interfaces for tracking

time. By theorizing and sharing the ultimate goals and, indeed, challenges of

the project even at its early stages, our aim in this paper is to answer Johanna

Drucker’s call to pay “[m]ore attention to acts

of producing and [to put] less emphasis on product” during “the creation of an interface” in order “to expose and support the

activity of interpretation, rather than to display finished

forms”

[Drucker 2013, 42]. In openly describing the unfinished form of The

Almanac Archive and its relationship to current scholarly trends, we

outline the technical and theoretical work going into its creation.

The Almanac Archive is a digital

project in its early stages of development that seeks to create a corpus of

annotated British almanacs from the Romantic century.

[1] Cheap and useful, the almanac was one

of the most commonly purchased, read, and annotated print genres during the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By focusing on historical readers’ annotations

in almanacs about everything from social engagements and weather to historical

events and the breeding of livestock,

The Almanac

Archive will offer insights into everyday life and ideologies of time

prevalent in Britain from 1750-1850. Upon its completion, it will bring duplicate

copies of almanacs from multiple library collections together, and one key goal of

the project is interoperability with aggregated sites within the

NINES network. Creating a searchable,

digital corpus of high-resolution images from almanacs annotated by contemporary

readers will encourage new research questions about the relationship between

historical events, individuals’ everyday lives, and the materiality of Romantic-era

interfaces for tracking time.

Anyone involved in building a digital project knows that technological,

methodological, and theoretical challenges often bleed into one another. However,

here we’d like to step back from some of the concrete technical aspects of

The Almanac Archive’s design and implementation to address

the theoretical and methodological questions that a project like ours poses across

fields, particularly Book History, Bibliography, and Digital Humanities.

[2] By theorizing and sharing the ultimate

goals and, indeed, difficulties of

The Almanac Archive,

even at its early stages, our aim in this paper is to answer Johanna Drucker’s call

to pay “[m]ore attention to acts of producing and

[to put] less emphasis on product” during “the creation of an interface” in order “to expose and support the activity of

interpretation, rather than to display finished forms”

[

Drucker 2013, 42]. In openly describing the unfinished form of

The Almanac

Archive and its relationship to current scholarly trends, we outline the

theoretical work going into its creation. Therefore, this article also engages

Kenneth Price’s assertion that we “need descriptions of digital thematic

research collections that highlight the editorial work and other types of

scholarly value that are added to the raw materials populating the

collection”

[

Price 2009, 28].

[3] In particular, our

approach to the issue of theorizing and encoding manuscript annotations in printed

books is especially relevant at a time when digital scholars’ interest in marginalia

has been increasing. In articulating the goals and challenges of

The Almanac Archive we also make a case for both

questioning what defines a duplicate copy in a digital project and, by extension,

seeking out and reproducing these so-called duplicate copies.

This article begins with a brief explanation of almanacs’ historical importance,

which shapes the form and goals of our resource’s creation as well as its unique

research potential. Understanding how readers used eighteenth- and

nineteenth-century almanacs makes clear how the genre offers scholarly research

possibilities that are not easily harnessed without digital tools. In the second

section of the article we consider the theoretical questions that our project raises

in dialogue with other theorists of digital and print media. In particular, we

explain

The Almanac Archive’s intended organizational

structure with reference to trends in digitization that often highlight what Jerome

McGann terms a text’s “linguistic

codes” over its “bibliographic

codes”; our archive aims to make the material features of almanacs,

including their annotations, as accessible as the printed content of the texts

themselves [

McGann 1991]. Finally, we end with a brief discussion of

the research potential of

The Almanac Archive.

Almanacs in the Romantic Century and the Digital Almanac in the Twenty-First

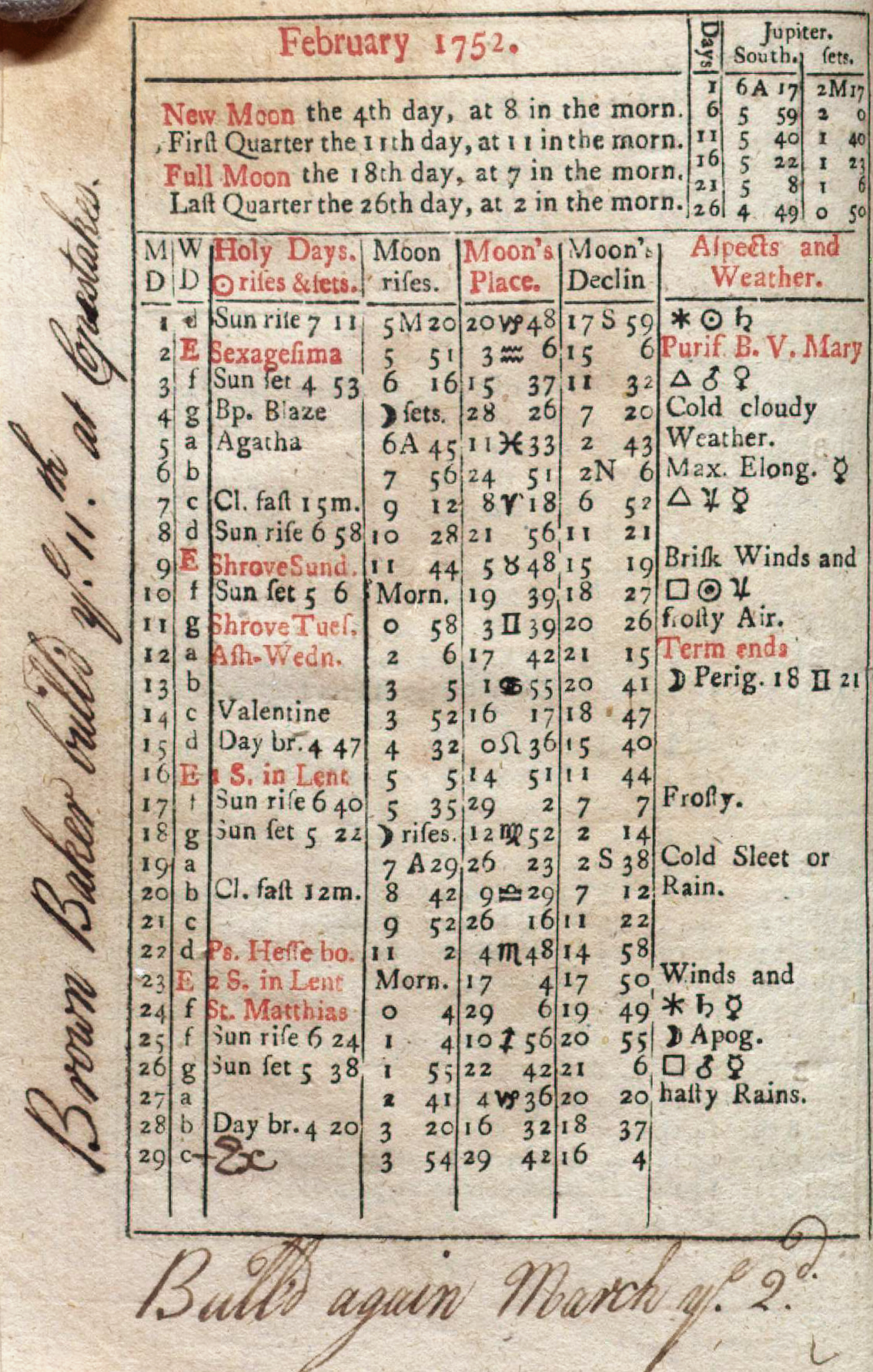

Unlike other print genres, almanacs and the marginalia that readers added to them

give us insight into both everyday life in the Romantic century and the

organization systems that people used to manage it. Offering information about

holidays, university term dates, hours of sunrise and sunset, predictions for

the future, and chronologies of historical events, almanacs were vital books for

a mass number of readers who recorded their observations and daily activities in

their pages. Importantly, almanacs didn’t simply provide a variety of

information; they provided diverse readers with the same standard information.

Variation certainly existed between different almanacs aimed as specific groups

of readers, such as farmers or lawyers; however, the genre as a whole was

largely unified (and, indeed unifying) in the basic, utilitarian information it

provided users about time, geography, tidal shifts, and history.

While almanacs were crucial reference tools, they were also for many readers

repositories of daily observations and records of both public and private life.

Studies of life writing from the Early Modern period to the nineteenth century

have noted that writing in almanacs was one of the earliest and most common

forms of diary keeping. Famous diarists such as William Gladstone and George

Washington began their diaries in almanacs, and far more common, of course, were

anonymous readers who noted births and deaths, daily activities, and memoranda

in their margins (see Figure 1) [

Gladstone 1968, 16]

[

McCarthy 2013, 11]. For example, Adam Smyth has identified

the practice of writing personal notes in almanacs as “the most common form of

self-accounting in early modern England”

[

Smyth 2008, 204].

[4] The almanacs’ prevalence and

their use as diaries increased in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as

growing numbers of people were able to purchase, read, and write in their

almanacs.

Our own research has recognized that many readers’ notes in almanacs respond

directly to the information and forecasts offered by the printed text. These

notes often contradict an almanac’s forecasts or record observations about

meteorological events that are not predicted by the almanac (see Figure

2).

[5] As

a result, almanacs are templates for comparing how numerous readers reacted to

the same natural and historical events and responded to the same or similar

texts.

Such comparisons are assisted by the capabilities of digital tools, and

The Almanac Archive is designed not only to showcase

the influential printed content of almanacs from the Romantic century, but also

to facilitate the large-scale study of reader habits and observations. Although

many single copies of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century almanac issues can be

found in digital repositories such as

Eighteenth Century

Collections Online (ECCO),

HathiTrust Digital Library, or

Internet Archive,

The Almanac Archive

provides users with distinctive ways of accessing and interacting with

this unique genre.

[6]

The Almanac Archive’s acquisition strategy is

motivated by what we might call thickness rather than breadth. Instead of

acquiring one digital copy of as many issues of as many titles as possible, our

archive aims to present many annotated copies of a single issue. And instead of

prioritizing transcriptions of the printed content of almanacs produced with OCR

or human transcriptions, our archive focuses on the accessibility of textual and

material features of these texts. To this end, we are using

carefully tagged page images rather than textual transcriptions as the primary

organizational units of the database.

[7] When completed, our resource will permit users to search for

a variety of fields related to both the material and the textual features of

almanacs from the binding of a particular copy of an almanac and its original

cost to the notes, marks, and drawings made by eighteenth- and

nineteenth-century readers. Users could, for example, search for any annotations

related to the weather made in the month of January 1801. The search results may

well turn up multiple copies of a single issue of a given almanac, enabling

users to compare how different contemporary readers responded to the same

information and the same text. Beyond simply reproducing almanacs for readers in

the digital age, then,

The Almanac Archive will

expose various and unique ways of organizing time and recording personal history

and will facilitate comparisons of reader observations. Moreover, as the

following section will discuss, these foci make visible the layered interactions

between text and Romantic-era reader that are cognate with those between digital

text and user.

Almanacs as Interfaces and the Problem of Duplicates

Almanacs are interfaces that embody ideologies about personal and historical time

as well as individual and national experience.

[8]

Drucker’s work on theoretical approaches to interface design applies to our

approach to representing this genre in digital form, for we are not only

interested in the almanacs as interfaces but in reflecting on the practice of

making the interface through which users of

The Almanac

Archive will engage with its content. In particular, Drucker argues

for interface design that makes evident the role of performativity in systems of

organization. She explains: “Multiple imaging modes that

create palimpsestic or parallax views of objects make it more difficult

to imagine reading as an act of recovering truth, and render the

interpretative act itself more visible”

[

Drucker 2013, 39].

The Almanac Archive avoids conveying a

uniform idea of

the Romantic-period reader by representing how

different readers approached, organized, and interpreted both time and their

books in unique ways. While the archive as a whole — its presentation of

published calendars and readers’ annotations about their lives and schedules —

may reveal certain patterns of thinking about time, individual copies with

readers’ annotations speak to the relational and interpretative nature of

reading and annotation. The resource, then, offers the type of palimpsestic

representation that Drucker has so convincingly praised. Thus,

The Almanac Archive is not primarily about discovering

truths about almanacs or annotation practices in the Romantic century, but

instead it is about conveying the numerous ways that readers adapted and

subverted, employed and rejected the structures of truth and temporality that

individual almanacs seemed to promote. Moreover, in allowing digital users to

access and analyze marginalia from different readers,

The

Almanac Archive will expose that historical users of the almanac

interface did not, in fact, view their own “reading as an act of recovering truth” but

rather as a layered act of reading

and writing that overlaid

printed facts with handwritten (and sometimes contradictory) observations [

Drucker 2013, 39].

Exploring readers’ annotations of and engagements with almanacs speaks to recent

trends in the study of reading history. H.J. Jackson’s

Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books (2002) and

Romantic Readers: The Evidence of Marginalia (2005)

are notable examples of this growing interest in readers’ annotations and their

potential value for tracking the history of reading. Even more recently, several

digital projects have sought to represent the history of reading and marginalia

through the creation of databases. For instance,

Annotated Books Online

(ABO) is “a digital archive of early

modern annotated books” that gives users “full open access to these

unique [annotated] copies, focusing on the first three centuries of

print”

[

Annotated Books Online 2014]. Spearheaded by the Universiteit Utrecht, ABO includes a variety of

materials from more than ten libraries and has several major partners, including

The Centre for Editing Lives and Letters (CELL) at University College London,

the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, and the University of

York. Like ABO,

The Archeology of Reading in Early Modern

Europe is large in the scope of its primary materials and its

partners, which include Johns Hopkins University, the Princeton University

Library, and CELL. The project “will

explore historical reading practices through the lens of manuscript

annotations preserved in early printed books” and has been awarded a

$488,000 development grant from the Mellon Foundation [

Shields 2014]. On a more grassroots level,

Book Traces, sponsored by NINES and the

University of Virginia under the leadership of Andrew Stauffer, “is a crowd-sourced web project

aimed at identifying unique copies of

nineteenth- and early

twentieth-century books on library shelves”

[

Book Traces 2014] (emphasis in original). Rather than focus on readers per se,

Book Traces acts as an argument for preserving unique

copies of nineteenth- and twentieth-century books that are at risk of being lost

or discarded after the content of a clean copy of the same text has been

digitized.

[9]

While each of these resources is unique, they are alike in the relative breadth

of their focus. By selecting a specific genre of books published within a

specific period and geographical location, we aim to create a much more focused

dataset, which highlights the importance not just of annotated copies but of

seemingly

duplicate copies of almanacs that have been annotated.

The originality of the resource is that it seeks to present and catalogue as

many copies of the “same” almanac as possible to facilitate comparison

between readers and different modes of reading. In presenting multiple

“duplicate” copies of almanacs and showing the diverse uses to which

users have put them,

The Almanac Archive presents

digitization as an argument for physical preservation, and the project

challenges the idea that material books are “in a kind of competition with

their own [digital] surrogates”

[

Stauffer 2012, 336].

The Almanac Archive uses digitization to

draw attention to the importance of retaining duplicate copies that, in

actuality, are quite different.

Moreover,

The Almanac Archive’s focus on 1750-1850

is especially relevant to duplicate copies, since the rise of the machine-press

period in the early nineteenth century made mass producing printed texts a real

possibility for the first time. Indeed, the Romantic century encompasses a vital

and volatile time in the material production of printed knowledge, yet the media

transition from the hand-press era to the machine-press era is one that is all

too often simplified and has led to unfounded, persistent assumptions about the

“sameness” of books from the machine-press period. Many scholars

working across disciplines and temporal periods acknowledge the crucial changes

in material knowledge production that marked the transition from the hand-press

to the machine-press period at the end of the eighteenth century. Laid paper

shifted to wove paper and, soon thereafter, to machine-made paper. The wooden

press that had remained substantially the same since Gutenberg gave way to the

iron-hand press in the early nineteenth century followed by an assortment of

other (steam-powered) presses that produced printed materials in unprecedented

quantities. Yet it wasn’t just the scale of print that grew; the uniformity of

the printed materials themselves also increased. The prominence of edition

binding, for instance, expanded rapidly from the 1820s onward, so that the

standardization of the covers of printed books aligned with the perceived

uniformity of their printed content.

[10] Such a narrative, of course, obscures the granularity of

technological changes while representing the production of material artifacts as

a flat teleology of technological advancement occurring at the expense of text’s

physical uniqueness or “aura,” to borrow Walter Benjamin’s term [

Benjamin 2001].

In fact, the transition between the hand-press and machine-press period was

gradual and the ability and desire to create uniform, duplicate copies has been

overestimated. As bibliographers have long realized, the variety and uniqueness

associated with early modern books is also “true of books printed after the

hand-press period”

[

Stauffer forthcoming]. One way to quantify this variation is to examine not only

“duplicate” copies of individual texts or editions (which Stauffer has

done with ten copies of the 1902 edition of the poet James Whitcomb Riley’s

An Old Sweetheart of Mine, each containing

significant bibliographical variants [

Stauffer forthcoming]) but also to

trace a largely-standard genre such as the almanac through this period of media

transition. Comparing duplicate almanacs as well as examining runs of particular

almanac titles across decades challenges the notion of sameness and duplication

in historical forms of printing and reading practices.

Yet, even while we advocate for digitizing and preserving duplicates, we still do

struggle with the logistics of digitally representing them. The question we

return to again and again is how much physical variation or annotation makes a

copy unique for the purposes of our project? A single word written in the

margins? A doodle? A mark? And how do we describe indecipherable or amorphous

marks in our database? In posing these questions, we recognize the necessity of

balancing our resource’s comprehensiveness with its usability. We are reluctant

to flood users with redundant search results containing duplicates with only the

most minor or indecipherable annotations, but we also want to create a resource

that users with research questions very different from our own can employ to

their advantage. The challenge, which continually returns us to the most

interesting and fundamental of digital humanities questions, is how to create a

database structure that categorizes and tags information in a way that permits

users to navigate and search effectively, while also minimizing interpretive

decisions on the backend that foreclose client-side interpretative

possibilities. For example, we initially considered dismissing some of the less

intelligible marks we encountered in almanacs — short horizontal lines penciled

next to given dates. However, even these small marks hold important research

potential. Maureen Perkins’s study of nineteenth-century almanacs notes that

women may have used almanacs discretely to keep track of their menstrual cycles,

for example, and such marks may constitute interesting and valuable data for

researchers interested in women’s studies or the history of sexuality [

Perkins 1996, 44]. The variety of uses that readers brought

to their almanacs — and which we are trying to illuminate through our own

resource — reminds us that digital resources risk precluding user

interpretations through the decisions their designers make while structuring

data. To mitigate these lost opportunities as much as possible, we aim for

transparency regarding the organizational principles structuring

The Almanac Archive. An article such as this one and

our decision to make available the archive’s

Metadata

Application Profile (currently in progress) embodies our desire to be

unabashedly open about the project’s development. Our goal is to make clear the

choices that have gone into the archive’s design from its initial inception to

its actual encoding by emphasizing on the frontend the inherently interpretative

choices that have gone into designing the backend.

Our decision to use page images rather than printed text as the primary

organizational units of the database is one means by which we hope to widen our

resource’s versatility, and it also stems from our questions about current

trends that privilege printed textual content as the primary unit of analysis.

Privileging print risks de-materializing books through digitization because it

substitutes an object’s original organizational structures for a “bag of

words” approach that, while useful for text-mining, has theoretical

limitations. Focusing on the unit of the page in

The

Almanac Archive’s design emphasizes and attempts to preserve the

importance of the page as a conceptual unit that shaped almanacs’ historical

uses in significant ways [

Mak 2011]. Prioritizing the page and

supplementing it with metadata,

The Almanac Archive

attempts to limit the appropriative, flattening elements that Hillel Schwartz

associates with copying technologies that take “without homage” and obscure “the historical steps that gave

rise” to the original and, in turn, its original uses [

Schwartz 2014, 191].

Theorizing

The Almanac Archive has therefore led us

to think critically about prominent ways of categorizing digital objects. In

“Digitizing Latin Incunabula: Challenges, Methods, and

Possibilities,” Jeffrey A. Rydberg-Cox describes five different

categories of digitization: Image Books, Image Books with Minimal Structural

Data, Image Front Transcriptions, Carefully Edited and Tagged Transcriptions,

and Scholarly and Critical Editions [

Rydberg-Cox 2009, 8].

The Almanac Archive fits into the category of

Image Books with Structural Data, yet we resist the connotations of

Rydberg-Cox’s term “minimal,”

for the metadata attached to each image and almanac will allow refined searching

by individual categories, such as publisher, place of publication, library

collection, type of almanac (i.e. astrological or agricultural), and type of

annotation (i.e. textual or pictorial). Thus, we challenge the idea that there

is a hierarchy of digitization involving various degrees of access to textual

content. Instead we conceive ways of digitizing that prioritize the

bibliographic unit of the page. Because the project recognizes and highlights

that almanacs were physical interfaces that users interacted with, we want to

avoid creating a digital interface that privileges either printed text or

manuscript annotations, but instead always displays the two side by side, in

relation to each other. John Bradley’s work on digital annotation has emphasized

how annotated texts involve “two rather different applications

[that] must co-exist”

[

Bradley 2012, 12]. While we agree that the different agents, intentions, and technologies

of the publishers and the annotators must be recognized, our archive seeks to

emphasize the codependence of these two applications. In this respect, our

approach prefers thinking of these applications as “overlapping hierarchies,” as Joanna Drucker

does, thereby recognizing the competing ways of valuing different linguistic and

bibliographic components of a digitized object [

Drucker 2007, 182].

The Research Potential of The Almanac

Archive

The unique research potential of our archive is a function of the fascinating

corpus and little-studied genre we have chosen and of our commitment to making

both bibliographic and linguistic features of the almanacs accessible to users.

By valuing equally annotations, printed text, as well as key metadata that will

be included in the archive, we resist privileging one type of information over

another. For our own research we will use the resource to track how eighteenth-

and nineteenth-century readers related to time and historical events, and we

will therefore focus primarily on the annotations found in the almanacs to

compare reader responses to time. Yet annotations also offer other avenues for

scholarly research. For readers unable to afford both an almanac and a dedicated

pocket-book diary, these volumes functioned as diaries. Because they were so

inexpensive, often costing between just one and three shillings, almanacs were

affordable to people who were unable to purchase other printed matter. Given the

characteristics and uses of the almanac in this period, the potential

applications for this project are diverse. Historians of weather, for instance,

might track weather patterns or climate change since users frequently noted

weather anomalies. Thus, material from

The Almanac Archive

might support other digital resources such as

Old

Weather, which invites users to transcribe weather-related

entries found in ships’ logs. Some almanacs include annotations about payments

to employees and other financial records, indicating that they may be untapped

resources for information about labour and economic history. Readers’ notes in

farming almanacs provide insight into historical agricultural practices.

While in some instances information about an almanac’s annotator remains unknown,

in others inscriptions of ownership or records of provenance provide key

information about annotators such as gender, occupation, geographical location,

and socioeconomic status. Aggregating these entries and this information will,

as the corpus expands, offer a new tool for historians, particularly those

interested in questions of everyday life and gender in Britain.

As compelling as the almanacs’ annotations and annotators are, we are designing

The Almanac Archive to foster other potential

areas of research. For example, the database will contain a metadata field for

the prices of almanacs. This information about price combined with information

about readers’ marginalia could help researchers make more concrete arguments

about annotation practices related to cost of books. The metadata will also

include information about provenance and how copies of almanacs are organized in

library collections. We have, for instance, noted that some users bound a series

of almanacs together. As our corpus of almanacs grows, it will be possible to

draw conclusions about not only the culture of annotating individual volumes but

also larger cultural value systems that impacted how groups of almanacs were

preserved and organized. As Thomas R. Adams and Nicolas Barker have suggested,

the survival and durability of different kinds of texts is an important variable

in any model of book history [

Adams and Barker 2001].

Of course, just as eighteenth- and nineteenth-century readers used the interfaces

of their almanacs in surprising ways, we anticipate that once the resource

becomes live scholars and teachers will use it in similarly original ways. The

flexibility and the variety of our archive’s applications, then, seem to embrace

in a digital, scholarly form the original aspects of the historical artifacts

that will comprise the archive itself. Ultimately, our archive’s unique research

potential lies in the light it sheds on the diverse and unexpected ways users

respond to structured data, whether in eighteenth-century printed texts or in

contemporary digital resources.

Works Cited

Adams and Barker 2001 Adams, T. and N. Barker.

“A New Model for the Study of the Book.” In N.

Barker (ed.), A Potencie of Life: Books in Society,

British Library, London (2001), pp. 5-43.

Benjamin 2001 Benjamin, W. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” trans. H.

Zohn. In V. Leitch, W. Cain, L. Finke, and B. Johnson (eds.), The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, Norton,

New York (2001), pp.1166-86.

Blagden 1961 Blagden, C. “Thomas Carnan and the Almanack Monopoly,”

Studies in Bibliography 14 (1961): 23-43.

Bradley 2012 Bradley, J. “Towards a Richer Sense of Digital Annotation: Moving Beyond a ‘Media’

Orientation of the Annotation of Digital Objects,”

Digital Humanities Quarterly 6.2 (October 12,

2012).

Drucker 2007 Drucker, J. “Performative Metatexts in Metadata, and Mark-Up,”

European Journal of English Studies 11.2 (August

2007): 177-91.

Drucker 2013 Drucker, J. “Performative Materiality and Theoretical Approaches to Interface,”

Digital Humanities Quarterly 7.1 (July 1,

2013).

Eckert 2015 Eckert, L. Reading Against the Interface: Almanacs and Hacking Practices

1750-1850 (Lecture). Books and/as New Media Symposium, Harvard

University (May 14, 2015).

Galperin and Wolfson 1997 Galperin, W. and S.

Wolfson. “Romanticism in Crisis: The Romantic

Century,” Selected Papers, Presentations and Other Materials from

NASSR 1996 and 1997.

Romantic Circles: A Refereed Scholarly

Website Devoted to the Study of Romantic-Period Literature and

Culture.

http://www.rc.umd.edu/reference/misc/confarchive/crisis/crisisa.html.

Gladstone 1968 Gladstone, W. The Gladstone Diaries, vol. 1, M. R. D. Foot and H. C.

G. Matthew (eds.). Clarendon Press, Oxford (1968).

Grandison 2014 Grandison, J. Negotiating Consensus: Reading Time and Space in

Nineteenth-Century Novels and Popular Print Genres. Ph.D. thesis.

University of Toronto (2014).

Mak 2011 Mak, B. How the Page

Matters. University of Toronto Press, Toronto (2001).

McCarthy 2013 McCarthy, M. The Accidental Diarist: A History of the Daily Planner in America.

University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2013).

McGann 1991 McGann, J. The

Textual Condition. Princeton University Press, Princeton

(1991).

Perkins 1996 Perkins, M. Visions of the Future: Time, Almanacs, and Cultural Change,

1775-1870. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1996).

Price 2009 Price, K. M. “Edition, Project, Database, Archive, Thematic Research Collection: What’s

in a Name?”

Digital Humanities Quarterly 3.3 (September 29,

2009).

Rydberg-Cox 2009 Rydberg-Cox, J. A. “Digitizing Latin Incunabula: Challenges, Methods, and

Possibilities,”

Digital Humanities Quarterly 3.1 (February 26,

2009).

Schwartz 2014 Schwartz, H. The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable

Facsimiles, revised edition. Zone Books, New York (2014).

Smyth 2008 Smyth, A. “Almanacs,

Annotators, and Life-Writing in Early Modern England,”

English Literary Renaissance 38.2 (2008):

200-44.

St Clair 2004 St Clair, W. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge (2004).

Stauffer 2012 Stauffer, A. “The Nineteenth-Century Archive in the Digital Age,”

European Romantic Review 23.3 (2012):

335-41.

Stauffer forthcoming Stauffer, A. “My Old Sweethearts: On Digitization and the

Future of the Print Record.” In M. K. Gold (ed.), Debates in the Digital Humanities, second revised

edition, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis (forthcoming).

Williams and Abbott 2009 Williams, W. and C.

Abbott. An Introduction to Bibliographical and Textual

Studies, 4th edition. Modern Language Association, New York

(2009).