Abstract

For over a thousand years, Tibet has preserved and translated ancient Buddhist Sutras

from India, keeping the tradition of Buddhist philosophy and meditation alive long

after it died out in India by the 12th Century. Recent efforts to digitize materials

from this textual tradition offer opportunities to broaden the circulation of rare

materials to the exiled Tibetan scholarly community, but also suggest conceptual

challenges arising from the complexity of the texts and their inherently multimodal

character. This paper describes the scholarly and meditative traditions from which

these texts come, and discusses possible approaches to their digitization.

For over a thousand years, Tibet has preserved and translated ancient Buddhist Sutras

from India, keeping the tradition of Buddhist philosophy and meditation alive long after

it died out in India by the 12th Century. The accuracy of the Tibetan translations of

Sanskrit Buddhist texts meant that modern scholars could establish the oldest versions

of Buddhist theories with some reliability. As the 19th Century scholar F. Max Müller

noted,

The Tibetan version [of The Buddha-karita of

Asvaghosha] appears to be much closer to the original Sanskrit than the Chinese;

in fact from its verbal accuracy we can often reproduce the exact words of the

original, since certain Sanskrit words are always represented by the same Tibetan

equivalents, as for instance the prepositions prefixed to verbal roots.

[Müller 1894, vii]

Known not only for their care in translation but also for their understanding of

Buddhism, Tibet’s monastic scholars added commentaries to the original Indian root

texts, and they established hundreds of libraries and universities where the texts could

be studied. Through the ages, Tibet’s ancient texts have received careful handling and

storage as sacred texts; they were printed by hand from wood blocks, wrapped in silk

covers, and stored on shelves behind the main altars of the shrine rooms in monasteries

and temples. Representing one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism — the Dharma — the texts

instruct Buddhists on how to achieve enlightenment.

But canonical texts represent only one piece of what has always been a multimedia

enactment of the key meanings of Vajrayana Buddhism, the particular form of Buddhism

that Tibet inherited from India. Vajrayana Buddhism (also known as Tantra) emphasizes

intensive meditation, but its meditation methods incorporate complex visual imagery,

bodily movements, the sounds of drums and horns, as well as the chanting of the texts

within the overall container of quiet meditation practice. Instructions on these

visualizations, bodily gestures and chanting practices have been passed down through

oral lineages, teacher to student, codified by sacred rituals in which monastics joined

together in learning and standardizing these practices.

Today the Tibetan textual tradition faces extinction unless serious efforts are made to

preserve it and the Vajrayana practices it supports. In the years following the Chinese

invasion of Tibet in the 1950s, Tibetan scholars struggled to preserve and circulate the

classical texts of their ancient Buddhist heritage. Many books were lost during the

1960s and 70s when the Chinese launched the Cultural Revolution on Tibetan soil,

destroying the libraries, temples, monasteries and universities in Tibet that had kept

the books safe. Some important, time-honored texts elucidating Tibet’s distinctive

Vajrayana meditation methods, liturgies and philosophical investigations may never be

found again, although the search by Tibetans still continues today for these famous

commentaries and instruction manuals.

The Tibetan scholars who fled into India first attempted to preserve the texts they

carried with them by printing the texts without delay. But at that time, the paper

available in India was of such poor quality (it was non-acid-free paper or rice paper)

that the print bled through from both sides, making the texts illegible [

Marvet 2006]. Many classical Tibetan texts were never reprinted at all but

were left in their original hand-printed, woodblock form (called “pecha” texts; see

Figure 1). The lack of facilities and poor economic

conditions for Tibetan refugees as they scattered abroad introduced added risks for the

storage of their paper texts. Simply transcribing the rescued texts and protecting them

in archives were stopgap measures. With Tibetan refugees living in India, Europe, North

America, South America, and other parts of Asia, it was impossible to establish

centrally located archives where all Tibetans could easily study the texts and learn the

highly detailed Vajrayana meditation methods described in the texts. When Western

scholars and meditators became interested in learning about Tibetan Buddhism, they also

found it difficult to locate or understand the old Tibetan texts mentioned in more

recent commentaries. Not only were indigenous Tibetan scholars unable to verify which

ancient texts had actually been preserved or where the texts had been stored, but the

iconography and complex symbolism associated with Vajrayana texts were not explained in

the texts themselves.

By the late 1980s Tibetan scholars recognized the possibilities of digital formats for

preserving their texts and for circulating the texts amongst the far-flung members of

the Tibetan community [

Chilton 2006]. Digitized texts could be made

accessible to Tibetan and western scholars around the world through the Internet, and

digital formats also made cataloguing the texts and searching for specific titles

easier, so that a more accurate assessment could be made of which texts had survived and

which texts were still missing. Several digitizing projects began in India, Nepal,

Europe and North America.

Today, after over a decade of work, there are digital archives of thousands of Tibetan

books.

[1]

For example, one of the Tibetan scholars committed to digitizing the Tibetan canon, the

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, established the Nitartha International Document Input Center

in Kathmandu, Nepal, with a team of Tibetan monks, Tibetan refugees born in diaspora,

and western computer specialists. At the Input Center, indigenous Tibetan scholars

represent classical Tibetan texts in digital formats that would be most useful for

Tibetan scholars in exile and for Tibetan translators. In addition to its digitization

of texts, Nitartha International has developed a Tibetan font software, several

informative websites on Tibetan Buddhism, and modern educational materials linked to

classical texts, such as CDs with interactive modules that outline the logic of

philosophical arguments, define basic concepts used in Buddhist philosophy, and

represent key points through visual images.

Recently, some indigenous Tibetan scholars have also begun to learn TEI encoding for

their digitized texts. The Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) is an XML language designed

for representing literary and historical texts. Maintained by an international

consortium of major universities, the TEI publishes detailed guidelines and

documentation of this language, maintains a listserv for questions, trouble-shooting and

general discussion amongst TEI users, and holds a yearly meeting for the hundreds of TEI

projects and encoders scattered around the world. What Tibetan scholars see in TEI is

not only a markup language, but a flexible text publishing method for digital texts, a

cataloguing schema for archiving the texts, and an application that will make it easier

to conduct analytical searches and link the texts to their translations. One obstacle to

using TEI (or any XML language) for the Tibetan canon is that Unicode for the Tibetan

language only became available recently, in partial form. Even though texts can now be

encoded in Unicode, they cannot be printed in the Tibetan Unicode script.

This example of Tibetan scholars experimenting with TEI for their ancient texts shows

the promise of TEI for multicultural texts. Multiculturalism as a theoretical approach

aims to respect the autonomy and value of other cultures. Recently, the TEI consortium

has initiated a project to translate its Guidelines into as many languages as possible

[

Rahtz 2005]. Without denying the very concrete economic and political

forces that create the Digital Divide, the TEI consortium intends to support indigenous

scholars as they protect and sustain their own textual traditions. In this way the Text

Encoding Initiative is expanding its work beyond its original North American and

European borders, becoming a global digital technology that is supportive of

multicultural textual traditions. The TEI consortium has welcomed Tibetan forays into

what started as a western scholarly undertaking, because TEI members understand that

text preservation by multicultural, and especially minority, populations is important.

Providing indigenous scholars and teachers with tools for keeping their textual

traditions alive helps secure the future for all the literatures of the world.

Not only is TEI an important strategy for preserving rare texts, but the TEI Guidelines

offer a standard set of schemas and documentation that is widely used in the

international scholarly community. By representing their texts through this scholarly

framework, indigenous Tibetan scholars can introduce their textual tradition to the

wider scholarly community. Over the centuries, Tibetan scholars have developed a

painstaking system for marking up the internal organization of their texts — a system

which delineates between several layers of scholastic commentaries on the original

Sanskrit root text. Its inherent complexity makes the Tibetan canon a natural for TEI

encoding. The TEI guidelines have been designed with complex historical texts in mind —

the texts expected to endure through the ages. The guidelines also offer specific ways

to represent the complicated scholarly features of historical texts. This precision of

TEI encoding is a good match for the complexity of Tibet’s commentarial tradition.

Tibetan commentaries form a nesting structure, such that later commentaries include and

surround earlier commentaries, which themselves include and surround the original Indian

Sutra.

[2] The Tibetan commentaries

proceed paragraph by paragraph, verse by verse, or sometimes even line by line in

explicating the meaning of the earlier text(s). All of these complicated internal

divisions of a text can be captured by TEI encoding. TEI encoding can also represent

linkages between texts, for example between the original Tibetan text and translations

of the text in western languages.

As an example, consider the following passage from a Tibetan commentary which concerns

the differences between two philosophical schools, the Consequentialists and the

Autonomists. The indented verses are from a root text, Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Verses on

Centrism. Generally, Tibetan commentaries such as the one below quote lines from the

earlier root text and then explain the meaning of that quoted passage in detail or

explore the philosophical debates that have arisen in response to that passage.

6.2.1.2.1.2.3.1.1.1. The system of the Centrists Following the

Sutras

In general, there originated many ways of commenting on the intention of

the text, The Fundamental [Verses on] Centrism [called] Supreme Knowledge

by noble Nagarjuna. However, these mainly fall under the two [schools of]

the Consequentialists and the Autonomists. The [first verse after the

eulogy] at the beginning of [Nagarjuna’s] treatise reads,

Not from themselves, not from others,

Not from both and not without a cause —

At any place and any time,

...Entities lack arising.

As for the way to explain the meaning of this [verse]: [First], through

the four claims of non-arising from the four extremes, master

Buddhapalita has invalidated the [four] antitheses [of these claims], but

did not set up any means to prove an actual thesis. Then, master

Bhavaviveka criticized the way in which Buddhapalita had formulated his

invalidation. He set up the [above four] initial sentences [about

non-arising] as autonomous [probative arguments] and also proved the

subject property in an autonomous way. After that, venerable Chandrakirti

explained how Bhavaviveka’s critique of Buddhapalita does not apply and

that Bhavaviveka’s acceptance of autonomous arguments in the context of

his own explanation of reasonings that analyze the ultimate is flawed.

Thus, he was the one who founded the tradition of the Consequentialists

in an extensive manner....

Example 1.

Passage from English translation of The Treasury of Knowledge

<head type="argument">6.2.1.2.1.2.3.1.1.1. The system of the <name type="philosophical school">Centrists</name>

Following the Sutras</head>

<p>In general, there originated many ways of commenting on the intention

of the text <title rend="italic">The Fundamental [Verses on]

<name type="philosophical school">Centrism </name> [called]

Supreme Knowledge</title> by noble <persName key="N1">Nagarjuna</persName>.

However, these mainly fall under the two [schools of] the

<name type="philosophical school">Consequentialists</name> and the

<name type="philosophical school">Autonomists</name>. The [first verse

after the eulogy] at the beginning of [<persName key="N1">Nagarjuna</persName>'s]

treatise reads,</p>

<q>

<lg>

<l>Not from themselves, not from others,</l>

<l>Not from both and not without a cause<mdash></l>

<l>At any place and any time,</l>

<l>...Entities lack arising.</l>

</lg>

</q>

<p>As for the way to explain the meaning of this [verse]: [First], through the

four claims of <rs type="basic argument"> non-arising from the four extremes</rs>,

master <persName key="BP1">Buddhapalita </persName> has invalidated the [four]

antitheses [of these claims], but did not set up any means to prove an actual thesis.

Then, master <persName key="BP2">Bhavaviveka</persName> criticized the

way in which <persName key="BP1">Buddhapalita</persName> had formulated

his invalidation. He set up the [above four] initial sentences [about

<rs type="basic concept">non-arising</rs>] as autonomous [probative arguments]

and also proved the subject property in an autonomous way. After that, venerable

<persName key="C1">Chandrakirti</persName> explained how <persName key="BP2">

Bhavaviveka</persName>'s critique of <persName key="BP1">Buddhapalita</persName>

does not apply and that <persName key="BP2">Bhavaviveka</persName>'s acceptance

of autonomous arguments in the context of his own explanation of reasonings

that analyze <rs type="basic concept">the ultimate</rs> is flawed. Thus, he

was the one who founded the tradition of the <name type= "philosophical school">

Consequentialists</name> in an extensive manner....</p>

Example 2.

TEI encoding of the same passage

The challenge in using TEI to capture these Tibetan materials lies in what escapes this

kind of basic encoding. Because the TEI was initially developed by scholars familiar

with the western textual tradition, features of some non-western textual traditions may

pose theoretical and practical challenges, and may require some adaptation of the TEI.

For example, one important feature is the enunciative mode associated with the text. It

is not irrelevant to Tibetan scholars whether a text is chanted, read silently,

transmitted by a teacher in a lung (a ritual that empowers listeners to practice

meditation or study denoted by the text), or scanned on a computer screen. Tibetans

believe that their texts do not simply record information but actually embody ancient

ideas or meanings that, in some situations, require appropriate methods of transmission.

Thus if we were to understand Tibetan texts according to a theoretical and operational

paradigm that treats them only as information, we would not only lose the original

Tibetan cultural context but would lose the different degrees of “transmission

power” said to be generated by different media (reading, chanting, lung

transmission, etc.) within the Tibetan textual tradition. This representation of the

enunciative mode, which is essential to practicing with Tibetan texts, might be

accomplished by additional, customized TEI elements for the chanted sections of the

texts.

Another challenging dimension is the readers’ actions in association with a text. Some

of the most advanced Tibetan meditation techniques include hand movements (called

mudras;

Figure 2 shows examples of these gestures), bodily

movements (such as prostrations), chanting, and complex visualizations. Texts are always

central to these meditation methods, but engagement with the Vajrayana text is far more

active than what occurs by simply reading or even chanting the text.

For example, one of the sections of the “Medicine

Buddha” meditation (which is used for healing) requires special hand movements

(mudras), performed while imagining a dark blue Buddha figure as one chants the mantra

of Medicine Buddha. The co-ordination of body (mudras), speech (mantra), and mind

(visualization of blue Buddha figure; see

Figure 3) is

difficult but necessary for the Vajrayana meditation practice. Instructions on how to

perform the mudras and how to chant the mantra are not in the Tibetan text itself; the

image of the blue Buddha is not in the text either. Traditionally, the mudras and chant

melody must be learned from a Tibetan teacher, and the visualization image is usually

memorized by focusing on a thangka painting in a shrine room.

These additional dimensions are not simply contextual information necessary to

understand the text being encoded: in an important sense, they are integral parts of the

text and its meaning, without which it cannot be said to be truly preserved. Tibetans

are intent upon preserving their textual heritage, but not simply as information in

storage. Instead, they aim for “real preservation” that records and encodes enough

of the living textual tradition so that the texts may be taken up again by future

generations in a way that continues Tibetan culture’s most meaningful values and

customs. Transcription or simple digitization of Tibetan texts constitutes mere

“storage preservation”; the texts may be read and studied in the future, but

their Vajrayana elements of mantra, mudra and meditation will not be captured, since

these elements need to be practiced “live”, so to speak, not just read. If a

Tibetan text sits in a library or a digital archive, but no one knows how to chant it or

meditate with it or debate in response to it, then the text has lost virtually all of

its meaning. The fossil of the text would be preserved, but the text itself would have

become extinct.

Real preservation requires the help of indigenous “text custodians” who teach the

traditional ways of working with the texts. This is a pressing concern because the older

Tibetan teachers who were born in Tibet before the diaspora will die in the next decade

or two. When they are gone, there may no longer be Buddhist practitioners who know

exactly how to chant certain texts or how to perform mudras in connection with specific

textual passages or how to lead more complex rituals based on the texts. To preserve as

complete a record as possible, so that the texts can live again in the meditation

practices and rituals performed with the texts, the gestural, musical and mental

dimensions of these texts must ideally also be recorded. Linking audio, video, and

images to the transcriptions may help, but it may also be worth exploring ways to notate

gestural and other information within the transcription itself. The TEI offers some

approaches to this in its chapters on transcription of speech and on performance texts,

and these could be extended further to accommodate the distinctive combination of

information carried in Tibetan texts.

The encoded TEI file can also form the basis of a more complex multimedia

representation. The TEI version of the Medicine Buddha liturgy can be linked to an audio

file of the correct pronunciation and melody of the mantra, to pictures of the hand

mudras that must be performed during the chanting of the text, and to a visual image of

the blue Buddha figure. The TEI transcription itself can also contain instructions on

how to perform the mudras or other bodily movements that occur at each point in the

text, allowing them to be displayed or suppressed as appropriate. By linking the TEI

transcription to multimedia resources, an editor could allow the appearance of videos,

graphics or photos as memory aids at certain points in the text, which would help the

reader/practitioner perform the visualization of the Buddha figure. An example is shown

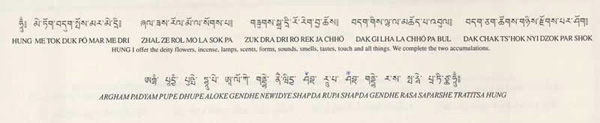

in

Figure 4, which gives the text of a chant in multiple

scripts together with a description of the mudras to be performed; these mudras are

illustrated in

Table 1 below. The practitioner's voicing of

the chant could be corrected or accompanied by an audio file of an indigenous Tibetan

chant master's articulation or by an audio file of Tibetan horns, symbols and bells.

| Argham |

|

| Padyam |

|

| Pupe |

|

| Dhupe |

|

| Aloke |

|

| Gendhe |

|

| Newidye |

|

| Shapda |

|

Table 1.

Diagram of mudras associated with Medicine Buddha text

Click for an audio file

of a Tibetan

mantra. Audio file © 2005 Karma Kagyu Institute. Chanted by Umdze Lodro

Samphel.

How could the Text Encoding Initiative help indigenous “text custodians” around the

world, who are struggling to protect their ancient cultural heritages? Ideally, we might

envision creating a simple shared descriptive system to facilitate the cataloguing of

endangered texts, so that international scholars become more aware of which texts have

been lost and which have been saved. Ideally such a system would be easy to learn, by

any scholar, working in any language. However, the significant differences between

textual traditions and descriptive goals make it hard to create a system that would be

both simple and widely agreed upon. It may be more practical to work on disseminating

TEI expertise more widely among “text custodians”. A second step, therefore, would

be to hold workshops on these digital technologies in the universities and teachers’

colleges of developing countries. The Digital Divide is closing in some parts of the

world (for example, India), and outreach from well-endowed scholarly communities to

poorer scholarly communities could include the sharing of digital methods for preserving

texts. Supported by occasional workshops, a virtual, international community of “text

custodians” trained in TEI could grow and bridge the Digital Divide between

developed and developing countries.

In this endeavor, it is important to respect the control that indigenous scholars have

over their own textual heritage. A textual heritage is a cultural property that can

speak to the world, but it should be maintained by the people whose ancestors created

it. If there are traditional rules about access to certain texts, digital technologies

should not bypass these rules. Digital technologies should not be used to appropriate

the world’s textual riches or simply to add inventory to western digital archives. The

model of broad “access” that often motivates western digitization efforts does not

apply universally, and may in some cases go directly against the indigenous textual

tradition. This issue comes up with regard to Tibetan texts, because some of these texts

are esoteric texts, reserved for advanced meditators. It is generally presumed by

western scholars that increased access to texts is better. But this presumption is not

shared by Tibetan scholars, who deal with texts that require special permission and

instruction from a qualified teacher before they can be read, studied, chanted or

memorized. The restricted nature of some Tibetan texts relates to the difficulty of the

meditation practices described in the text. Not everyone has advanced meditation skills

or sufficient commitment to undertake the mental training methods relayed in the text.

Before the Chinese invasion of Tibet, there were monastic libraries that contained

esoteric volumes which never circulated beyond the monastery or even amongst all members

of the monastery. Thus although most western scholars do not consider “trespassing”

a serious textual practice crime, Tibetan scholars might regard TEI-encoded texts as

inviting trespassers. This is why it is essential for any multicultural development of

TEI to involve indigenous scholars, who understand the threats faced by their endangered

textual tradition and are committed to protecting it.

When a culture is endangered, as the Tibetan culture is, members of that culture not

only try to preserve its texts but try to continue the rituals and other practices that

keep the culture alive. Transcribing texts and digitizing them are important

preservation methods, but these methods need to be supplemented with other tools for

awakening the texts from their archival slumber. The benefits of TEI encoding for the

Tibetan canon range from enhanced preservation of the texts and greater accessibility

for scholars, to support for the continuation of Vajrayana meditation practices that

renew the Tibetan Buddhist heritage. Despite the challenges of reconciling Tibetan

textual assumptions and western digital methods, especially if Tibetan scholars

themselves learn to apply TEI encoding there is a chance that 21st century technology

will not leave the ancient Tibetan textual tradition behind.

Why are modern digital methods such as TEI encoding so important for endangered Tibetan

texts? There are a couple of reasons. First, digital text applications support the

Tibetan scholarly community, which is spread across the globe. Online digitized Tibetan

texts can be accessed by a Tibetan in exile no matter where he or she has taken up

residence. The circulation of texts is made easier when the cataloguing and searching of

texts follows standardized guidelines, and TEI encoding provides just this kind of

standardized information. The other side of this point, however, is that the exiled

Tibetan scholarly community lacks the kind of financial support that a government would

normally provide for modernizing its textual tradition; this community must rely on the

largesse of western scholarly institutions. By concerning itself with the plight of

endangered textual traditions, the Text Encoding Initiative might provide aid to these

Tibetan scholars in exile.

Another reason is that TEI encoding gives the Tibetan textual tradition entrance to an

international scholarly enterprise that may make it easier for non-Tibetans to

understand Tibetan Buddhism. Even though the Tibetan Buddhist tradition is being lost on

its home soil, an international Tibetan Buddhist culture is appearing. Scholars and

meditators in Europe and the western hemisphere are studying Vajrayana Buddhism and

practicing its meditation methods, liturgies and philosophical debate techniques.

Vajrayana Buddhism depends upon the direct transmission of teachings from a qualified

teacher to students, but there is also a virtual dimension to this spread of Tibetan

Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhists often go online to find information and to communicate with

one another; digital technologies have been used to forge connections between western

newcomers to Tibetan Buddhism and indigenous Tibetan monks and nuns. Compared to the

restrictions on the study and practice of Tibetan Buddhism within Tibet itself, there is

greater freedom online to discuss the issues and share the achievements that are

important to Tibetan Buddhists. This global Tibetan Buddhist community is forming with

the aid of digital communication tools unavailable twenty years ago. The adoption of TEI

encoding will add a scholarly tool to this digital toolkit.

Finally, the rich heritage of Vajrayana Buddhism cannot be represented by a

one-dimensional medium. Its exuberant visual imagery, its complex symbolism, its

deep-toned chanting and music, and its engagement of the body in ritualized motions

combine within the most advanced meditation practices. Although Tibetans do practice

quiet, unmoving meditation, what is distinctive about the Tibetan tradition is the

overabundance of forms — painting, music, ritualized gesture, chanting, dance, even

formal philosophical debate — within its meditation practices. Digital technologies

capture this rich dimension of Tibetan texts better than the simple transcription of

texts can. Because TEI encoding offers ways to release a Tibetan liturgy, meditation

manual or philosophical inquiry from its text-cocoon and express its full

multidimensionality, TEI is one of the digital technologies that holds promise for

preserving the Vajrayana textual tradition.

Acknowledgements

- Jeff Hoogmoed, http://www.freespacegraphix.biz

- Union College East Asian Studies Freeman Foundation grant

- Union College Humanities Faculty Development grant

- Editors of Digital Humanities Quarterly

- Photographs courtesy of Tenzin Namdak, Nitartha International Document Input

Center, Kathmandu, Nepal and Karma Triyana Dharmachakra Monastery, Woodstock,

NY

- Audio file courtesy of Karma Kagyu Institute, Woodstock, NY